Many members of Atlantika Collective have close ties to Ukraine and other post-Communist and Socialist states around the world. This week, as part of our response to the invasion of Ukraine by Russia, we issued a Special Statement on Ukraine, condemning the cruel and illegal invasion and urging strong actions to defend the country and to safeguard human lives that are in grave danger.

In addition, we unveiled a new section of our website, The Post-Communist and Socialist World, that highlights the many projects that members have created that originate in Ukraine or other nations of the world that have transitioned away from communism and socialism.

Now, other artists are joining us in support of Ukraine by adding links to their projects to this new section of the website. Today, we’re featuring the voices of two very talented artists, Victoria Crayhon and Matt Mooore, who have created beautiful and insightful projects in this part of the world.

Karl Marx Street I, Irkutsk RF 2018, Archival Pigment Print, 30 X 44 inches, Victoria Crayhon.

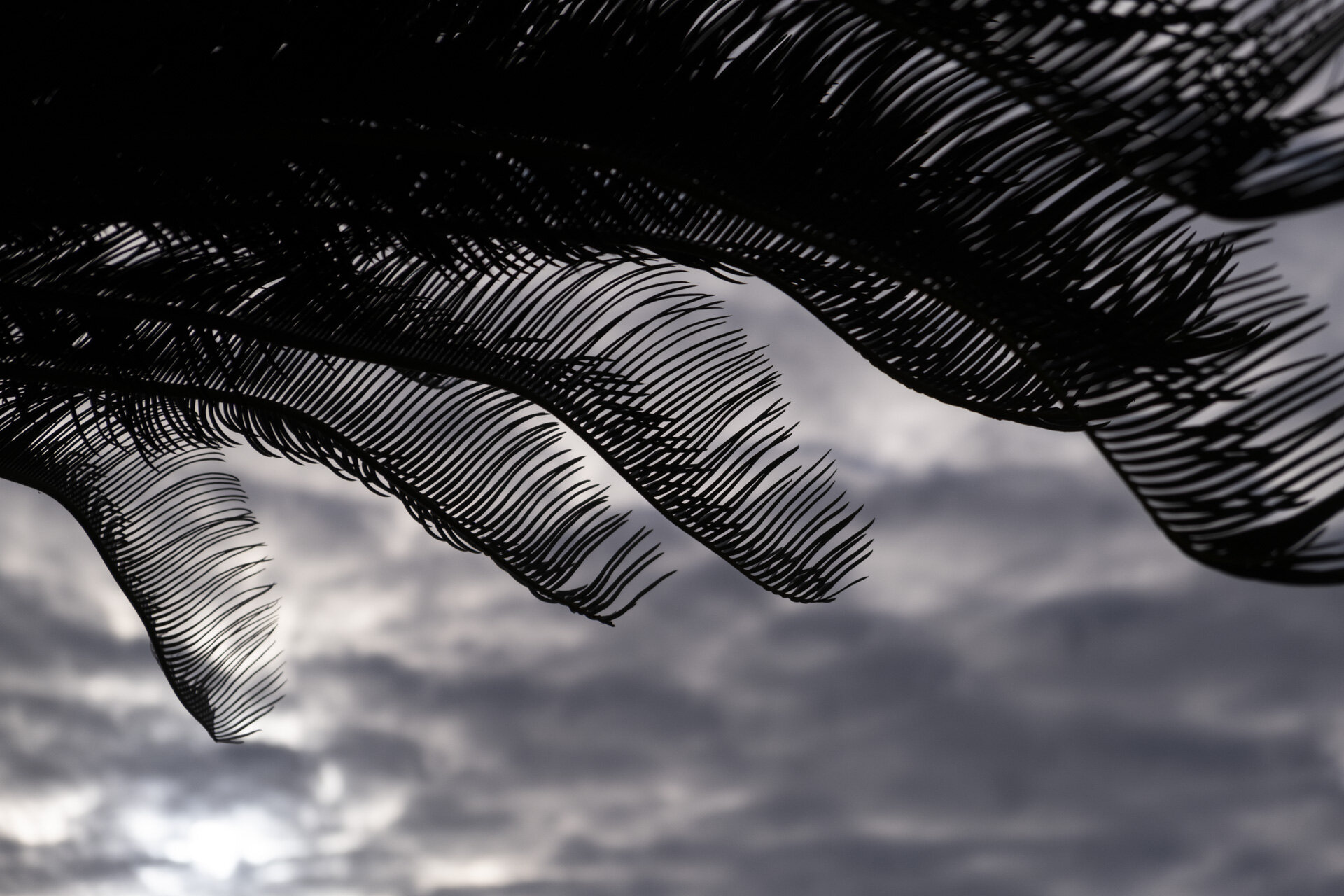

Victoria Crayhon has been making photographs in the Russian Federation since 2011. Her work examines the intensity and omnipresence of Russian nationalism as reflected in its architecture, public space, historical sites, holiday rituals, and culture in general, which, like any form of nationalism, is essentially the glorification of one’s own culture and country. Nationalism has historically, at least in the west, led to two world wars and most American wars since 1945. Her two projects, New Empire and Far East, ask the questions: How long can a society hold onto and/or reject ideas from its own history? Which facts and stories are being told? How is history wielded and for whom?

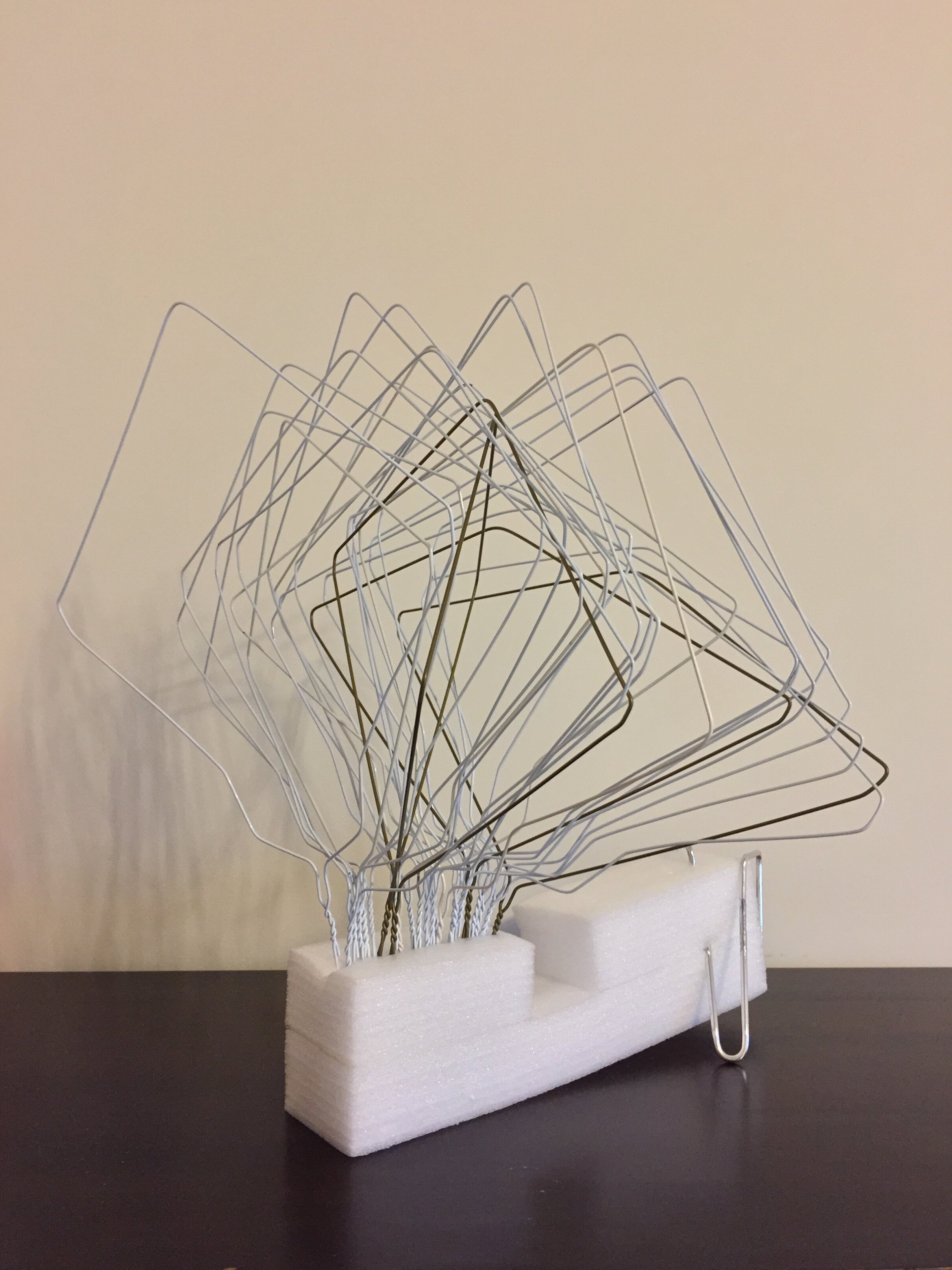

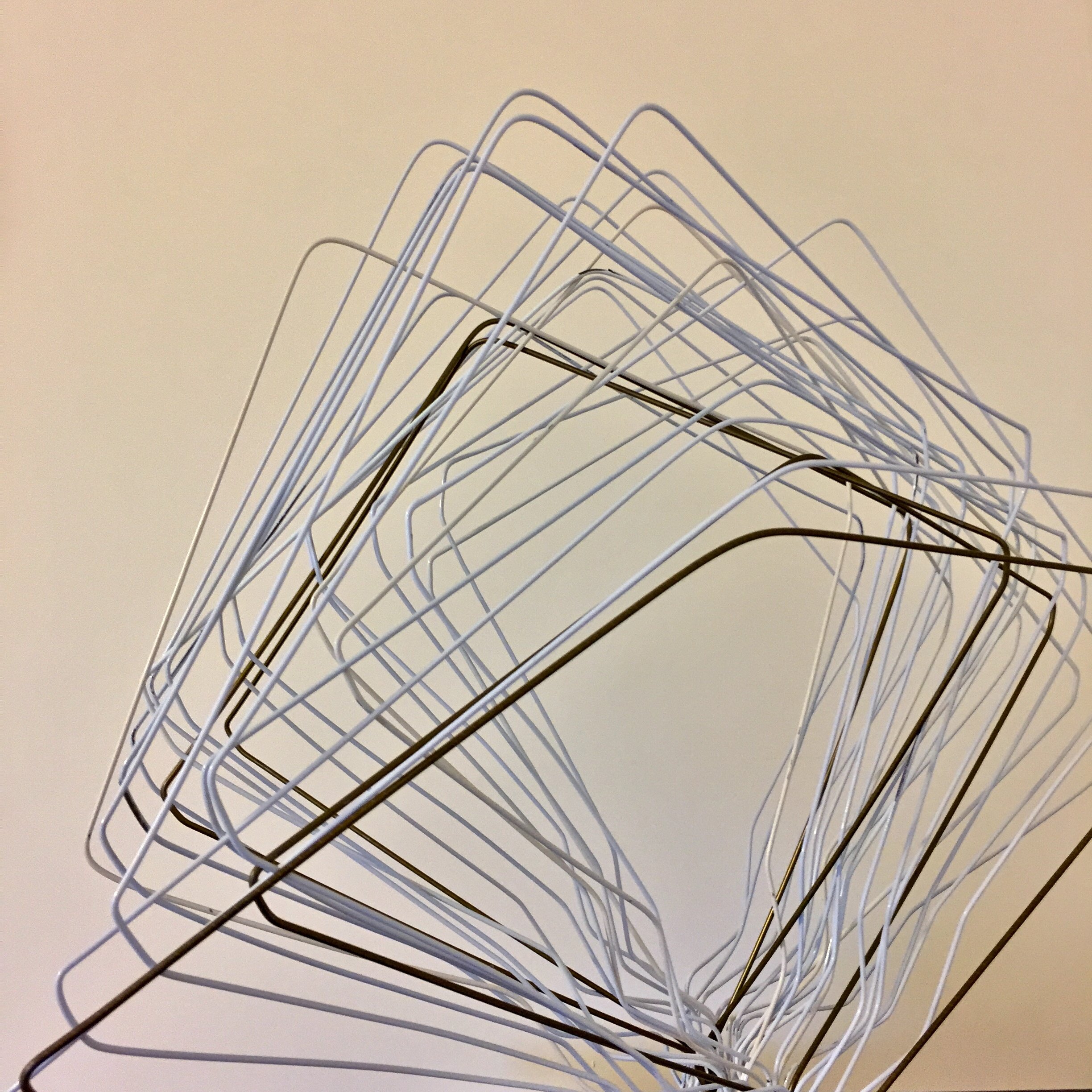

Post-Socialist Landscapes by Matt Moore is an exploration of memory sites in countries that were at one time occupied by the Soviet Union. The photographs in this project fall into two main groups. One set of images depicts the exact location where statues of Lenin and Stalin once stood. A second group of photographs focuses on the fate of the discarded communist monuments that once stood throughout Europe’s Eastern Bloc states. Together, these two groups of photographs speak to the way local governments and municipalities control historical narratives through the manipulation of public and private space. While some societies go to great lengths to eradicate the unwanted reminders of their past, others are willing to let them slowly disintegrate.

Lenin, Vilnius, Lithuania, Matt Moore, 2014.

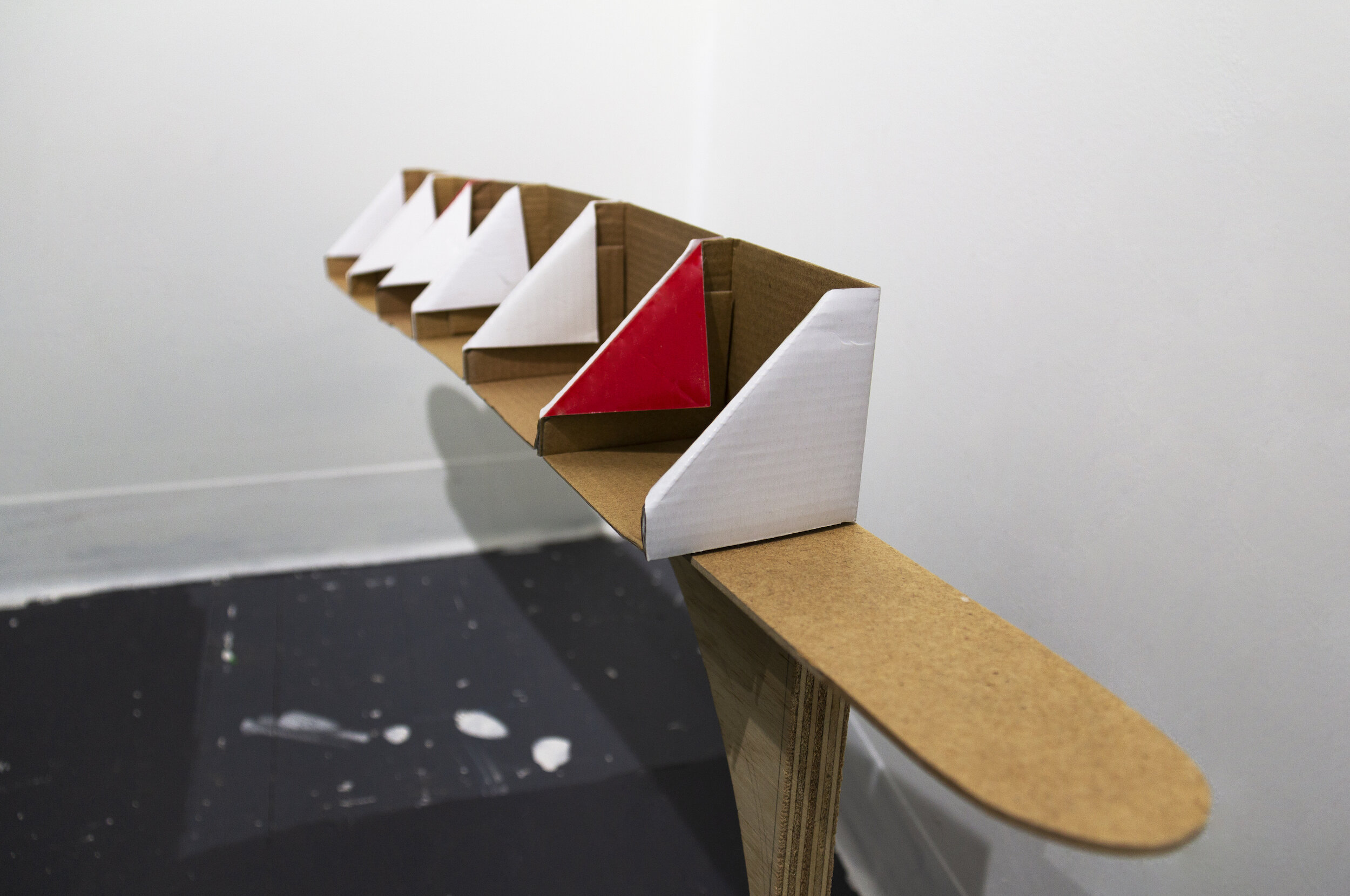

Moore’s project East/West presents images of the abandoned checkpoints that separate former eastern bloc countries from the West, particularly the Czech Republic from Austria and Germany. As remnants of the Iron Curtain, each checkpoint carries with it its own amount of history and aura. Today, each structure stands vacant and serves only as a hollow reminder that one is moving from one country to another. Moore is interested in them as symbols of the perpetual change that takes place in Europe and beyond. Ultimately, the images in this project function like time capsules. They give us a glimpse of the past, while also hinting at the potential for greater change ahead.

In addition to featuring talented artists from around the world, our new section on the Post-Communist World contains information about how you can do your utmost to assist the people of Ukraine in their historic struggle for democracy and self-determination, including information on Russian war crimes, charities that are assisting Ukrainians in their country and those who have been forced to flee, and suggestions about how to contact government officials in the West who must hear from us about the importance of this crisis for the world.

We all have a stake in the war in Ukraine, since the very future of democracy is at stake. We continue to urge everyone to do all they can to influence the outcome.