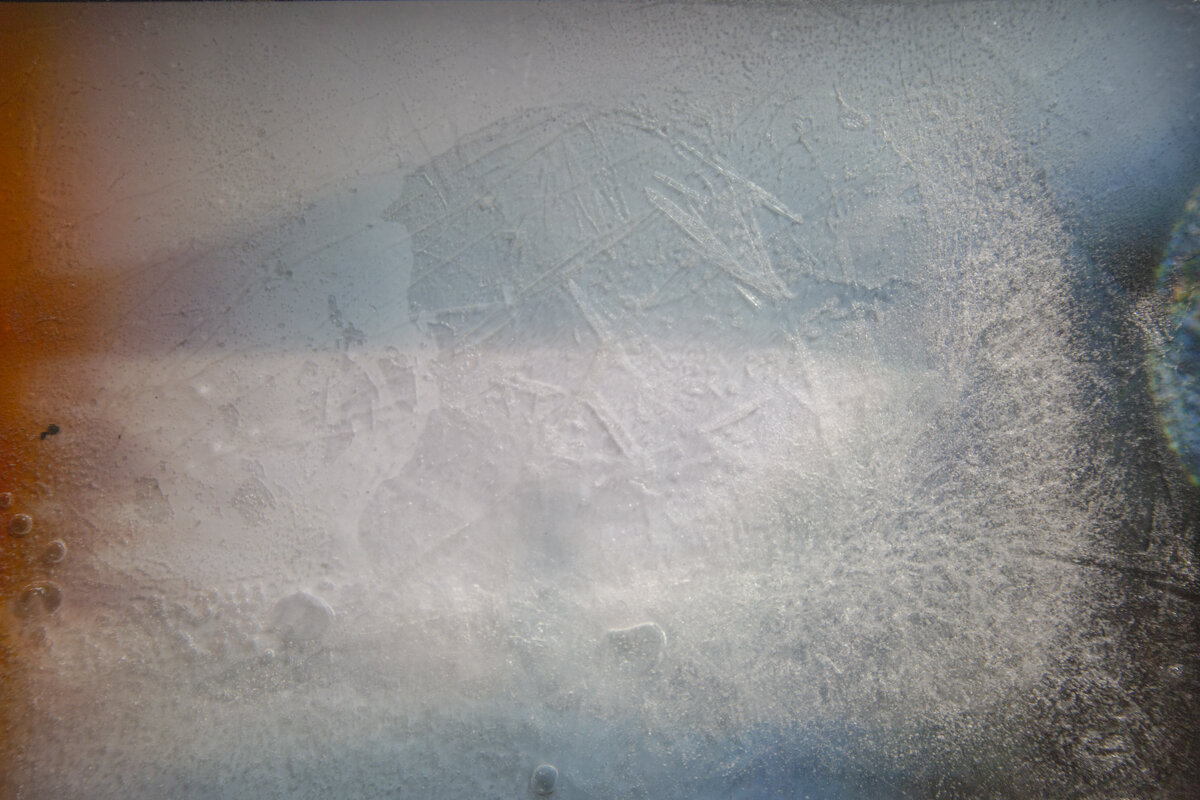

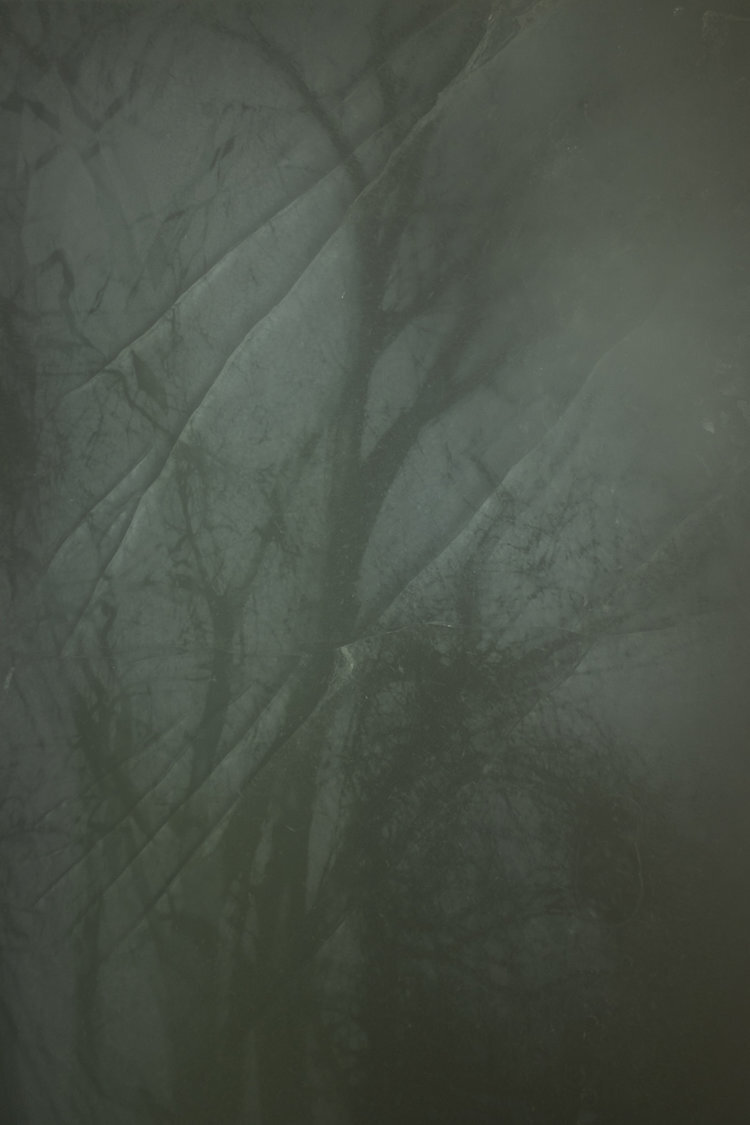

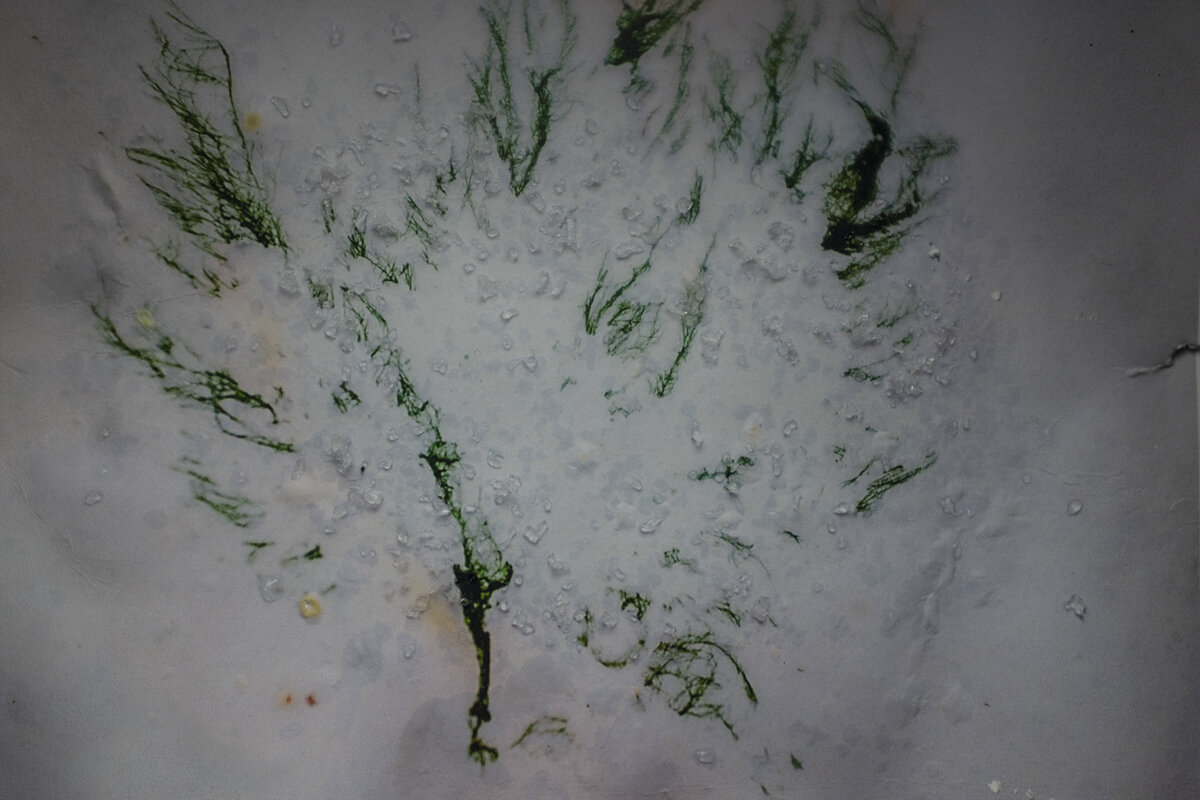

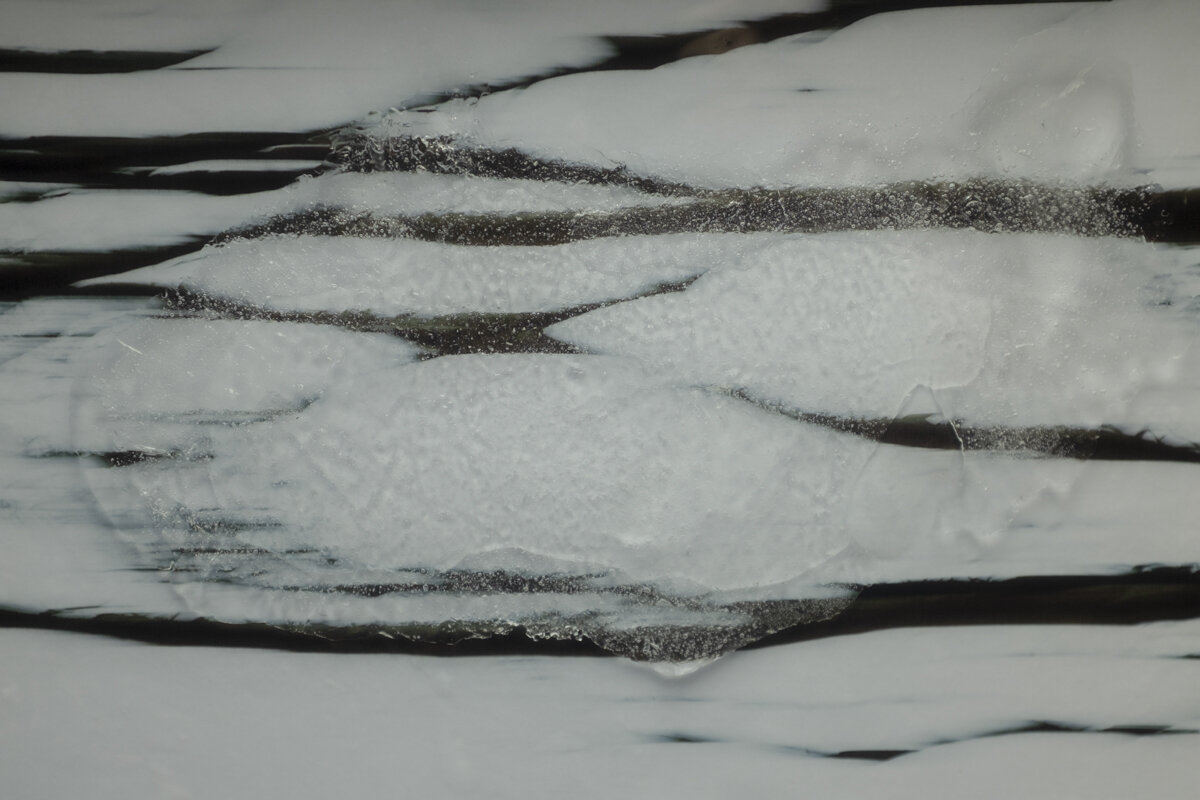

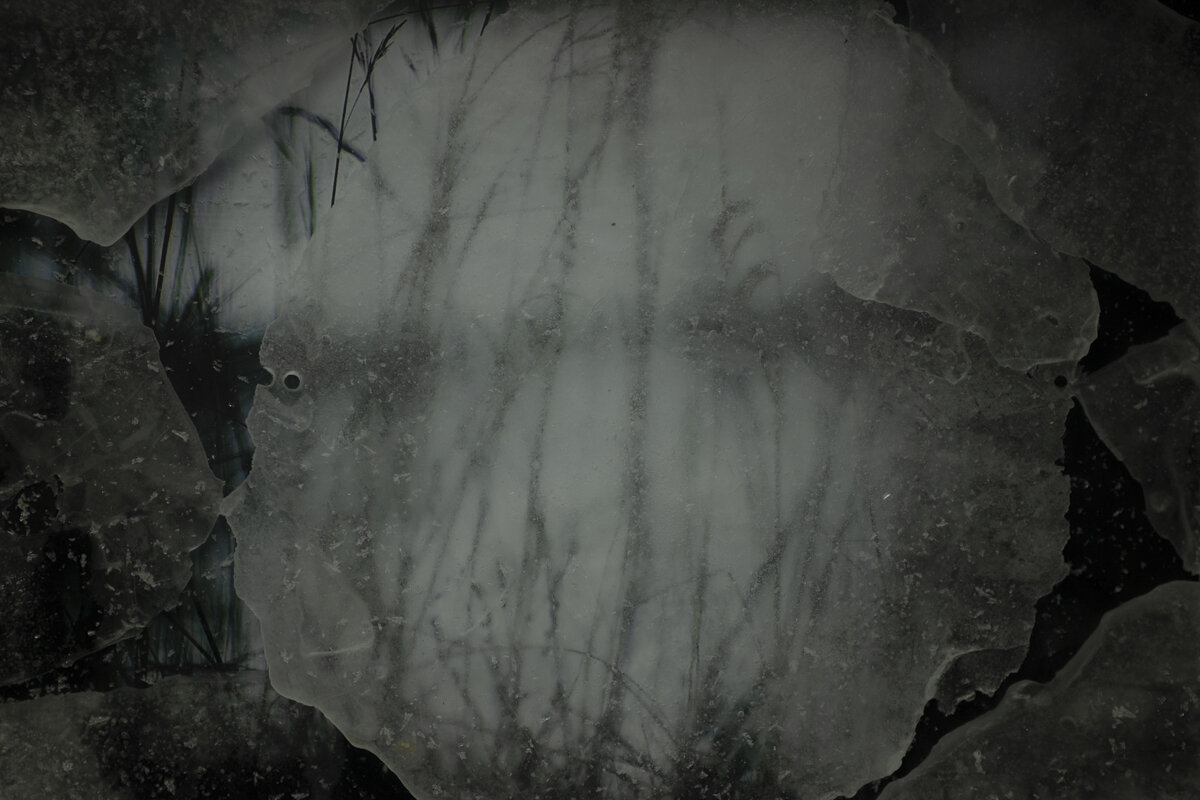

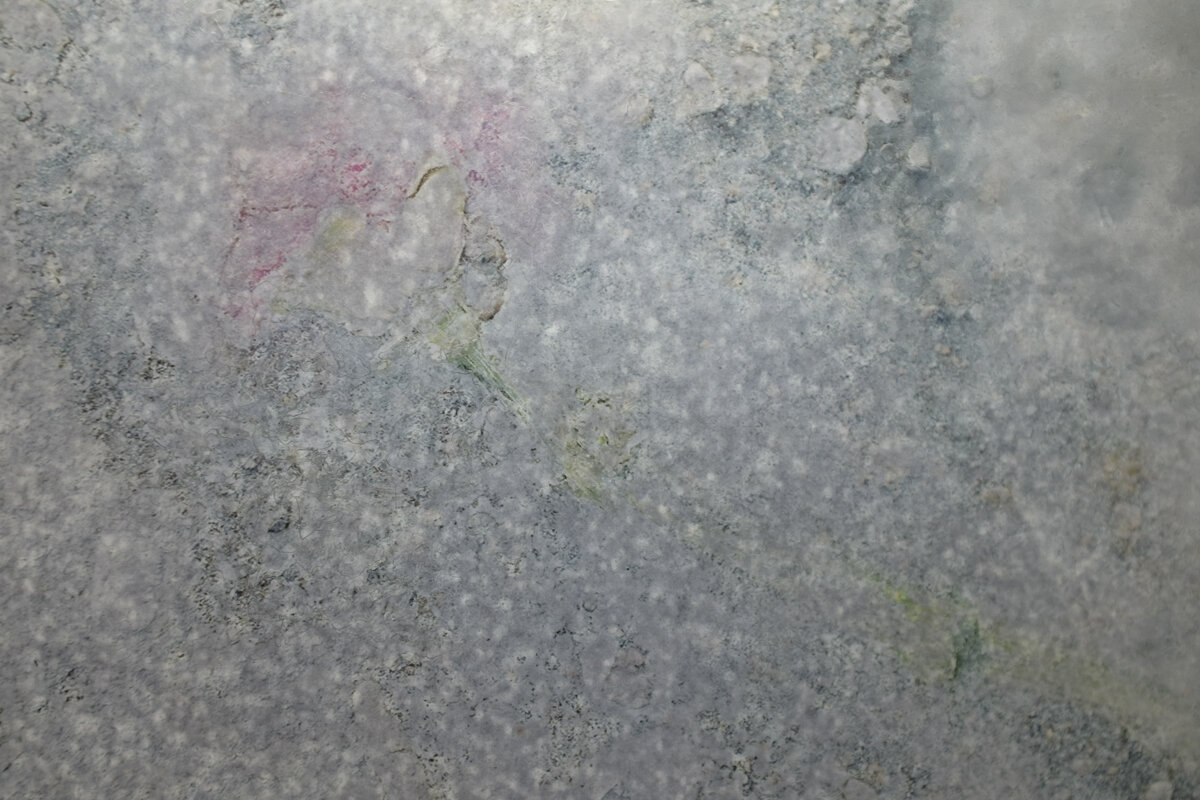

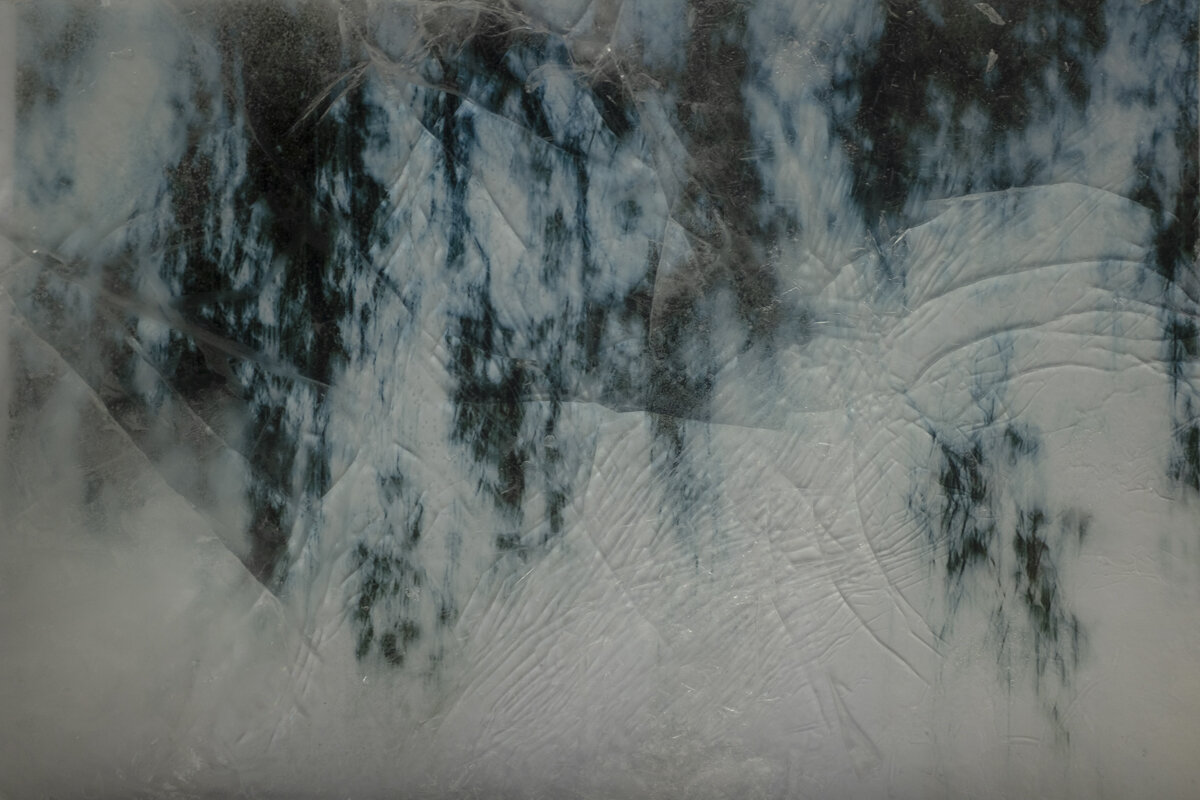

Shallow Frieze is a collection of experimental photographs that we created of Lake Baikal’s landscape that were frozen in ice and then rephotographed during a melting process. These photographs directly comment on the problem of global warming, which is occurring more rapidly in Siberia than most places in the world. Research by Russian and international scientists demonstrates that Baikal’s ice cover, critical to its many endemic species, is significantly shorter and thinner than a century ago. These warming trends are already contributing to changes in the Lake’s precious ecosystem, from tiny plankton to the world’s only freshwater seal.

It’s comforting to think of getting back to normal, but we’re already marooned somewhere quite distant from that. And rather than try to get back, we need to fight our way forward to a new place. Normal must be lashed, scraped, smashed, eliminated, excoriated, demolished.

And to do that, we need new paradigms, a leap forward, in our thinking. We got a glimpse of quieter, cleaner cities during lockdown. In the New York Times, Farhad Manjoo recently asked, "What about cities without cars?" Not as fanciful as we think, this solution has the potential to simultaneously clean the environment, save lives, expand park space, and improve health.

In the political realm, there’s always a tension between what we know we should do and what’s “politically realistic” given the power of the fossil fuel industry and its allies. But there’s considerable evidence now that the economy is moving faster than politicians. Recent studies show that solar and wind plants are already more economical, in every major market around the globe, than existing coal-fired plants. While regressive leaders cling to archaic paradigms in the hopes of solidifying their base and preserving dying jobs, a report issued in 2018 by, yes, the Trump Administration, makes it eminently clear that climate change could have a devastating impact on the American economy, eliminating as much as one-tenth of the nation’s GDP by the year 2100.

The Green New Deal is often criticized for being too sweeping and unrealistic in part because it links climate change to social justice issues. But isn’t that exactly what the pandemic demonstrates? “I can’t breathe” are not just the dying words of George Floyd on the streets of Minneapolis, but they are the words of people of color dying from COVID-19 in disproportionate numbers, and they are the words of poor and working class people who are more frequently exposed to contaminants and pollution in the environment, causing serious health problems and premature death. (If this sounds like hyperbole, then be aware that more than 90 percent of people in the world breathe unhealthy air, causing 7 million deaths per year.)

Greta Thunberg is outspoken about the fairness issues at play in the climate crisis. She is quoted in Time Magazine recently saying,

On average the CO2 emissions from one single Swede annually is the equivalent of 110 people from Mali in West Africa….The vast majority of the global population...are already living within the planetary boundaries….The climate and sustainability crisis is not a fair crisis. The ones who’ll be hit hardest from its consequences are often the ones who have done the least to cause the problem in the first place.

And while we all need to do our part and be willing to compromise on our lifestyle to limit greenhouse gas emissions, there’s a firm case to be made that the rich have outsized impacts, and need to be at the head of the line in making changes. Around the world, regardless of country, the wealthy often own several large houses, drive multiple cars long distance, fly frequently, and use energy at a rapid clip. As British scientist Kevin Anderson put it in the Guardian recently, “Globally the wealthiest 10% are responsible for half of all emissions, the wealthiest 20% for 70% of emissions.”

If the rich were forced to cut their emissions to the level of an average citizen, Anderson estimates, we could cut greenhouse emissions by one-third. The catch, of course, is that wealthier citizens, industry leaders and top policymakers are among the most powerful and don’t easily embrace far-reaching changes, choosing to sublimate the fact that their own children are the ones who will be paying the proverbial piper. Anderson says, “Many senior academics, senior policymakers...have decided that it is unhelpful to rock the status quo boat and therefore choose to work within that political paradigm – they’ll push it as hard as they think it can go, but they repeatedly step back from questioning the paradigm itself.”

If climate change is not just an environmental issue, but a social justice issue, it forces us to consider how to claim more power so we can accelerate change. Recent history in the United States sadly does not suggest we’re good at maintaining meaningful movements. After all, what happened to Occupy Wall Street, The Women’s March, the March for Our Lives on gun violence, etc.? We don’t hear much about them anymore.

But it’s possible we’re in the middle of something a tad different. The Black Lives Matter protests, which occurred in hundreds of cities across America, are variously estimated to have included between 6 and 10 percent of all Americans, making it potentially the largest protest movement in US history. (That’s not counting the many solidarity protests abroad, including the one we joined in Bratislava, Slovakia.)