Atlantika Collective member Yam Chew Oh recently showed eight sculptures at Material Index, the Young Talent Exhibition at Affordable Art Fair (AAF) NYC 2021. Curated by Keren Moskovitch, Material Index features works that explore the relationship between the artist, materials, and identity. The three artists in the exhibition, including Arantxa Ximena Rodriguez and Lisa DiDonato, employ the physicality of material to express solidarity with transcultural origins, and animate individual and ancestral memory.

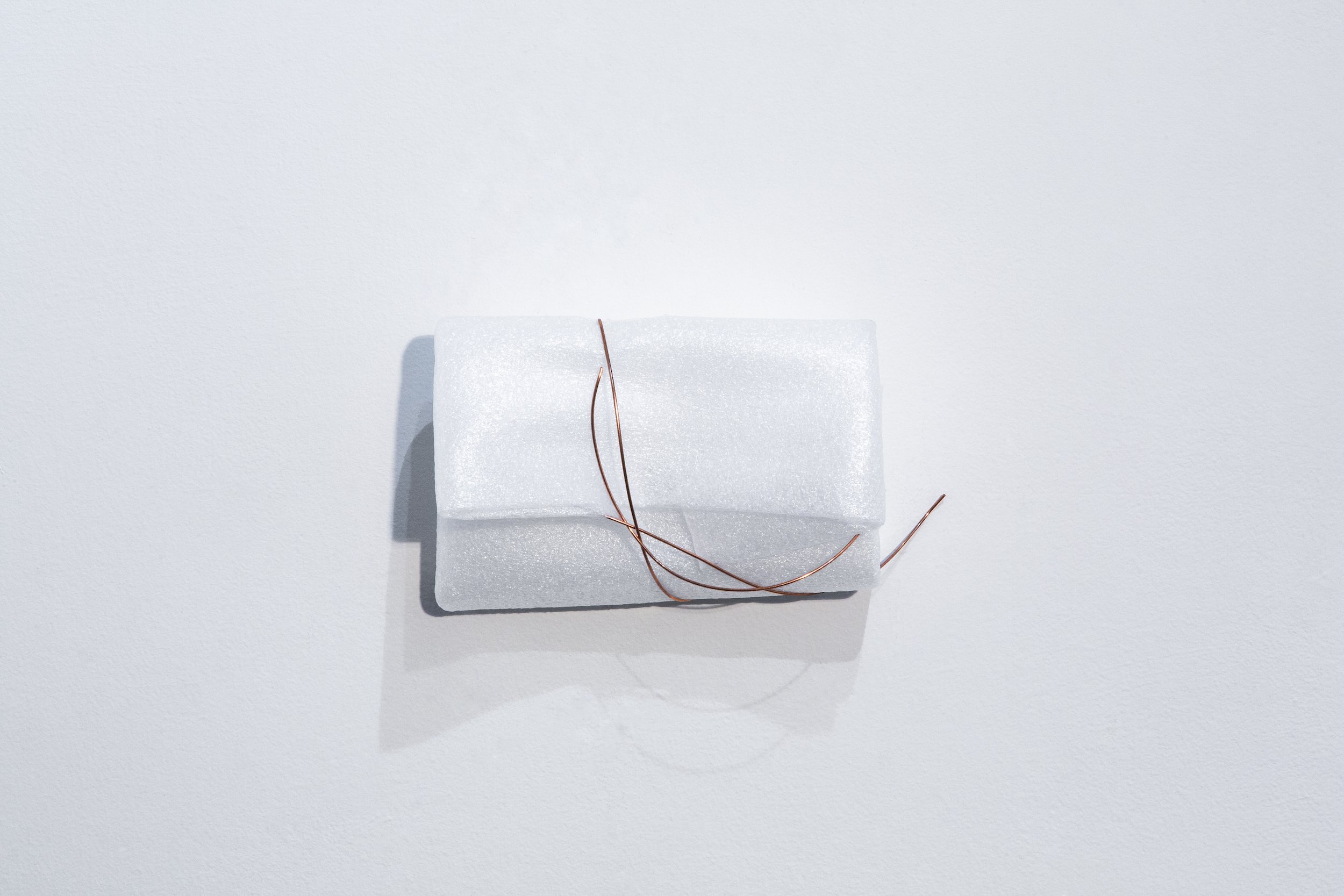

Floating on detritus (2018)

I love you, warts and all (2017)

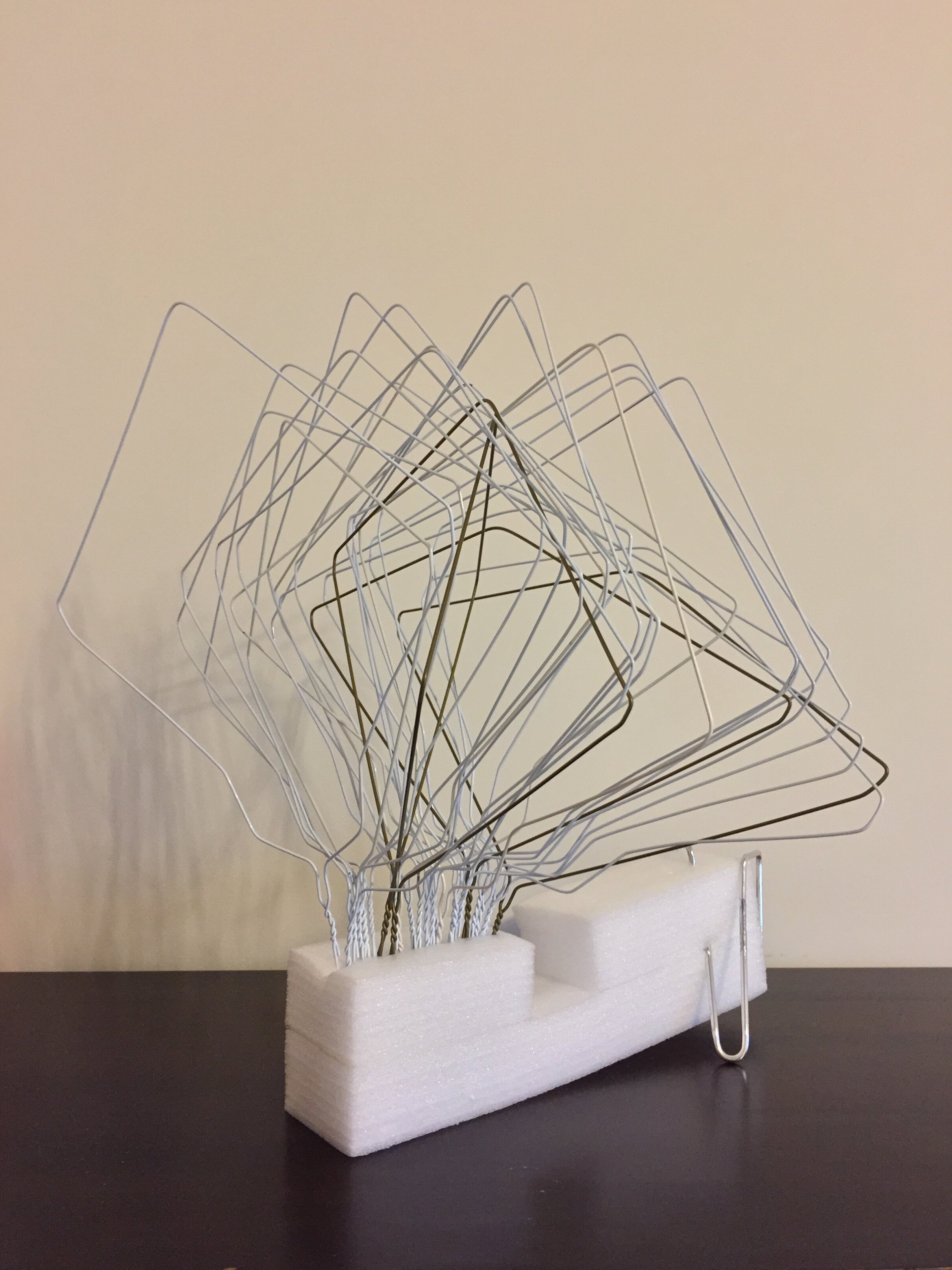

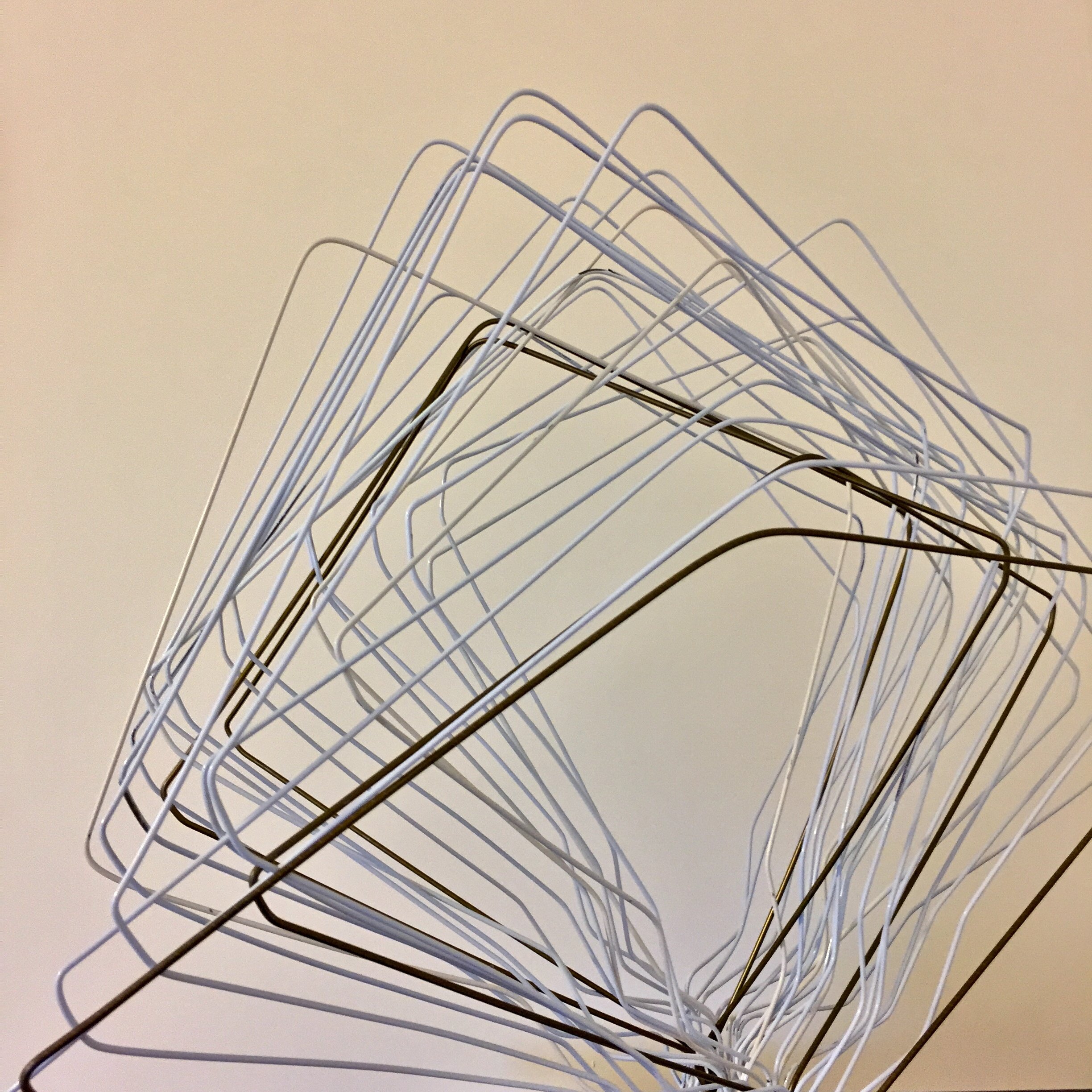

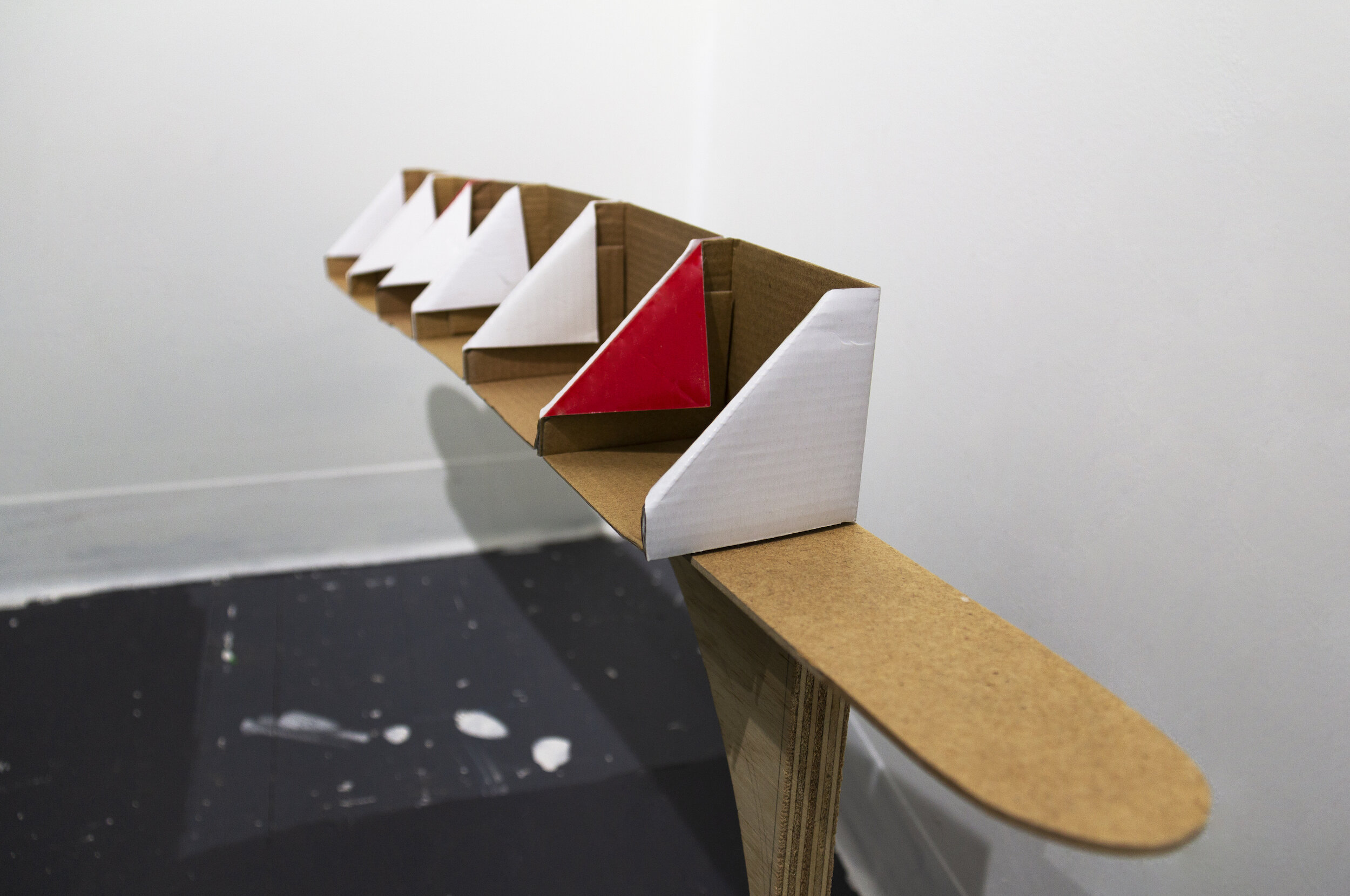

Oh is a multidisciplinary artist, educator, and storyteller whose work explores circumstance, time, and attention through history, relationships, and the everyday. His late father was a karung guni man, the Singapore equivalent of the rag-and-bone/junk man, who scavenged and sold used and unwanted items for a living. Growing up, helping his father with his trade had a deep impact on Oh's love for discarded and found materials, and how he treats them. He privileges the humble, overlooked, and flawed through gestures aimed at protecting the past and accentuating the now. “My sculptures and assemblages reflect the characteristics of karung guni, in particular, modesty of means, precarity, and transformation,” says Oh.

The karung guni man (rag-and-bone) (2018)

The Vow (2018)

The works that Oh exhibited at the AAF were made mostly in 2018 and early 2019; the former was a year of immense challenges and deep introspection. Oh survived appendicitis surgery, related complications, and six bereavements. He shares that, throughout that potent period, he thought a lot about family, relationships, mortality, and the fragility of life and time. “The sculptures in Material Index reflect the frames of mind and states of being I was in when I made them—they are intimate and emotional manifestations of personal stories, life- changing moments, and precious memories that I’m afraid to lose.”

You've also been naughty lately! (2018)

A different kind of love (2018)

Memory's DNA (2018)