Dana Fritz and Larry Gawel recently showed their exhibit, Landscapes: East and West at the Ryniker-Morrison Gallery in Billings, MT and presented their work to the Atlantika Collective as part of the group’s “First Saturday Artists Talks.” Dana Fritz and Larry Gawel present the land as a source of nourishment and imagination through 19th and 20th century photographic processes. Fritz and Gawel have lived in Nebraska for over two decades but have traveled extensively throughout the American west as well as Japan making photographs about their experiences. While the two artists often travel together, their distinct perspectives and engagement with ideas and the land itself are revealed through their photographic processes.

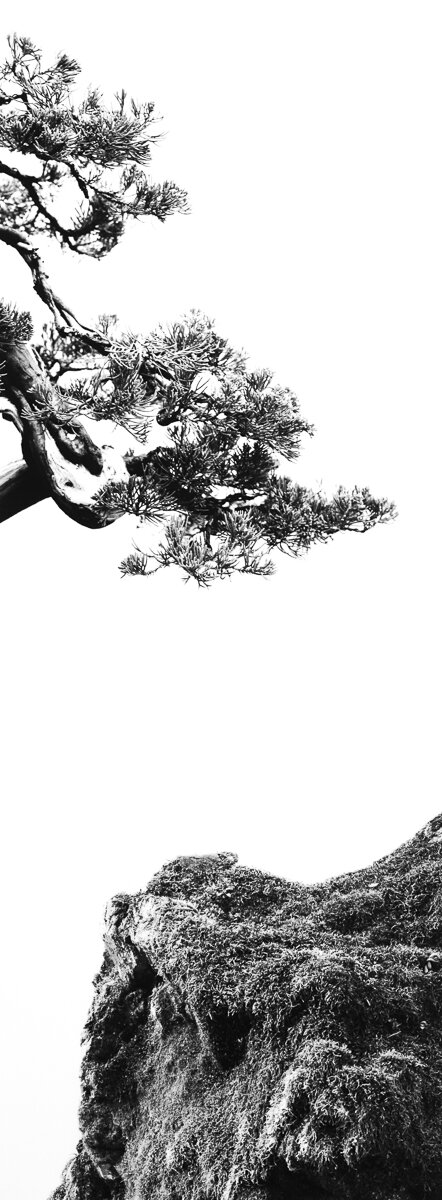

Dana Fritz’s Views Removed renders trees, stones, and other natural materials in ways that their scale and perspective become ambiguous, combining more than one negative to create a "landscape view" that exists only in the final print. The composition and contrast in the resulting gelatin silver prints emulate the white paper background and equivocal space in ink painting traditions that are free from the technical constraints of photography. Comprising negatives shot in Japan as well as the American west, the combination prints are inspired by questions about Eastern and Western pictorial space, landscape as construct, and the inherent tension between the real and ideal.

Larry Gawel’s Land : Mine is an over-arching project concept for multiple photographic pieces and bodies of work made since 2009. Comprised of gelatin silver prints, dryplate tintypes, and tintype lumens, Land : Mine explores the various facets of Gawel’s relationship with the land. As a gardener, forager, hunter, angler, and traveler, this relationship is as personal as it is rewarding. Tintype images from the Harvest series document plants and animals that are harvested from the land for consumption; Silver gelatin photographs explore the meditative qualities of repetition in Tokyo Treeline Meditation; Unique direct-positive silver-prints memorialize spent shotgun shells found on public hunting lands in the series Collect.

Juniper Moss, Dana Fritz

Matsushima 2, Dana Fritz

Toadstool Park 1, Dana Fritz

Collect-Detail, Larry Gawel

Tokyo Treeline Meditiation 09, Larry Gawel

All the Leaves of a Stinging Nettles Plant- Detail, Larry Gawel