by Gabriela Bulišová & Mark Isaac

Undoubtedly we are now in a moment when there is a surfeit of threatening news from many places around the globe. We see outrageous lies and disinformation, racism, hatred, war, atrocities, the rise of anti-democratic forces, the ongoing degradation of the natural environment, and an accelerating climate crisis. We also recognize that these crises are now linked together, amplifying each other and creating a complex and increasingly dangerous “polycrisis.” It’s hard to know how best to respond. And for many of us, it’s hard to know how to manage the spiraling negative emotions associated with these events.

As artists and as members of Atlantika Collective, one of the most rewarding benefits of exhibiting work and collaborating with others is the opportunity to create bonds with those who are doing their part to stand up for truth, tolerance, justice and humanity. Over the past two years, we’ve found that repeatedly in Poland, a rare bright spot where the populace rallied and rejected the nationalist, right-wing government previously in power and are now fighting to restore democracy. Over and over, we’ve met individuals who are going to extra lengths to preserve a meaningful civic life, to preserve cultural memory, to fight against xenophobia, and to embrace all those who are a part of the community.

Our most recent trip, undertaken to shift our exhibition from Białystok to Sejny, in far northeast Poland, was exemplary in this regard. During our Fulbright experience in Poland (2022-23), we repeatedly heard about the work of the Fundacja Pogranicze, or Borderland Foundation, based in Sejny and Krasnogruda. As its name implies, the Foundation has long been devoted to maintaining and celebrating diversity and coexistence between peoples. In general, their mission is to develop “a new civic formation which both knows and respects the tradition of their place of residence…and creates an open society, respecting otherness.” They pursue this both in their own borderland region of Poland, close to Lithuania and Belarus, but also in multicultural locations around the globe.

However, it was not until recently, long after our Fulbright grant ended, that we witnessed the Foundation in action and understood the extensive impact of their work. We give thanks first to Wieslaw Szuminski, who not only curated and supervised the hanging of our exhibition, but welcomed us warmly into the community. Wieslaw is an exceptionally talented artist whose own highly accomplished projects are an incredible inspiration to us. We are also deeply appreciative of the kind welcome offered to us by the visionary leaders of the Borderland Foundation, Krzysztof Czyżewski, Małgorzata Sporek-Czyżewska, and by Agata Szkopińska. We feel very lucky to be linked to all of them, and it is our ardent hope that this is just the beginning of a lasting friendship and collaboration.

We are also especially indebted to the scholar, educator, and author Marci Shore, a professor of intellectual history at Yale University, who selflessly took on the job of translating our remarks during the opening into Polish. She is a remarkably accomplished scholar who is adept in multiple languages and along with her husband, historian Timothy Snyder, is doing more than her fair share to fight against many of the most disturbing political developments in the contemporary moment.

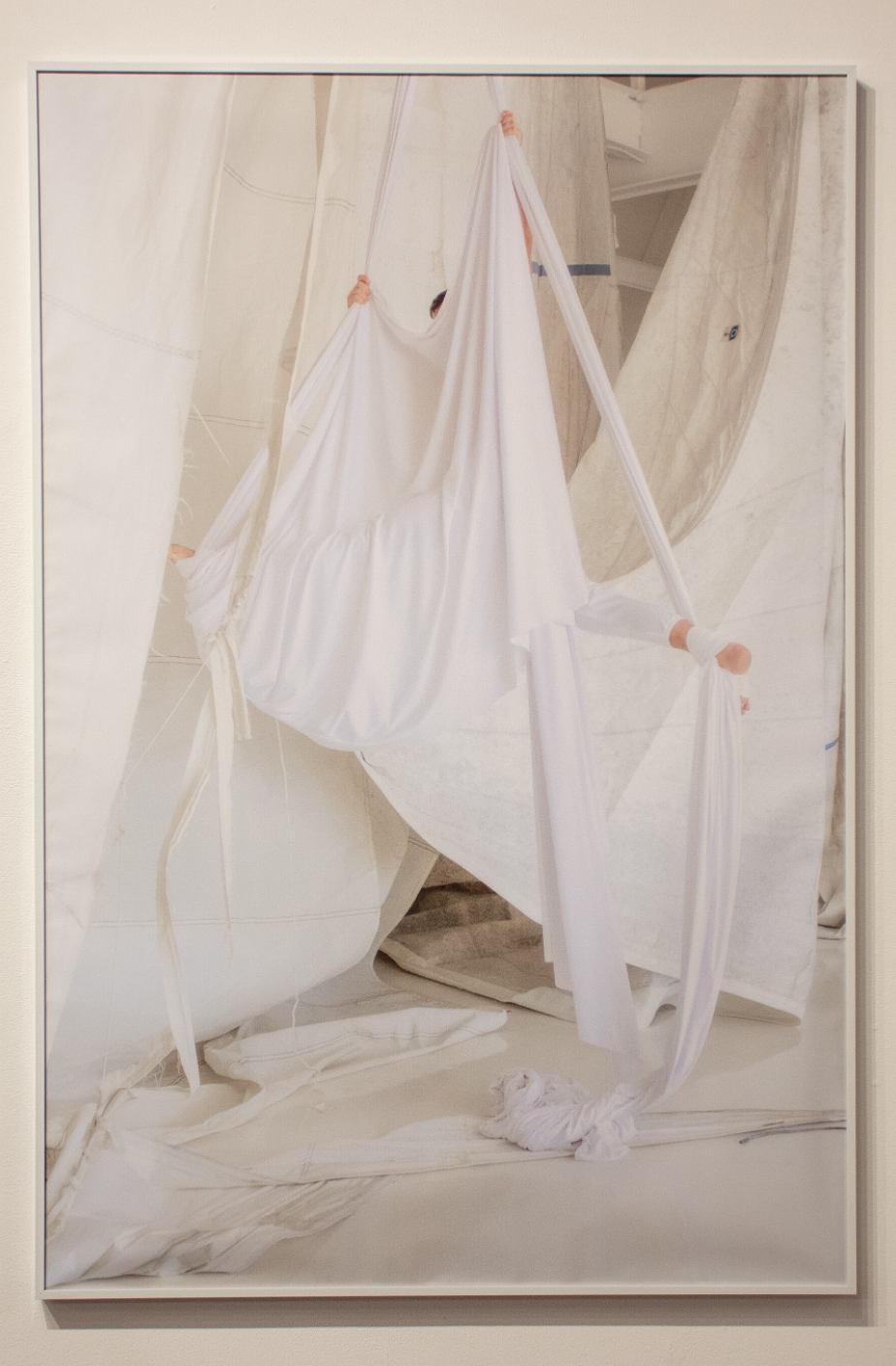

Our project, titled The Landscape of our Memory, is currently on exhibit in Sejny’s renowned White Synagogue, which was built to replace its wooden predecessor in 1885. The synagogue now serves as a cultural center administered by the Borderland Foundation and also as a site of cultural memory for the Jews of Sejny, many of whom were lost during the Holocaust. It is therefore a uniquely appropriate site for the exhibition, which seeks to commemorate those lost during the “dispersed Holocaust,” or the mass killing of Jews that occurred in or near people’s hometowns, rather than in concentration camps like Auschwitz. Entire generations, grandparents, parents, children, vanished into mass graves in a matter of seconds.

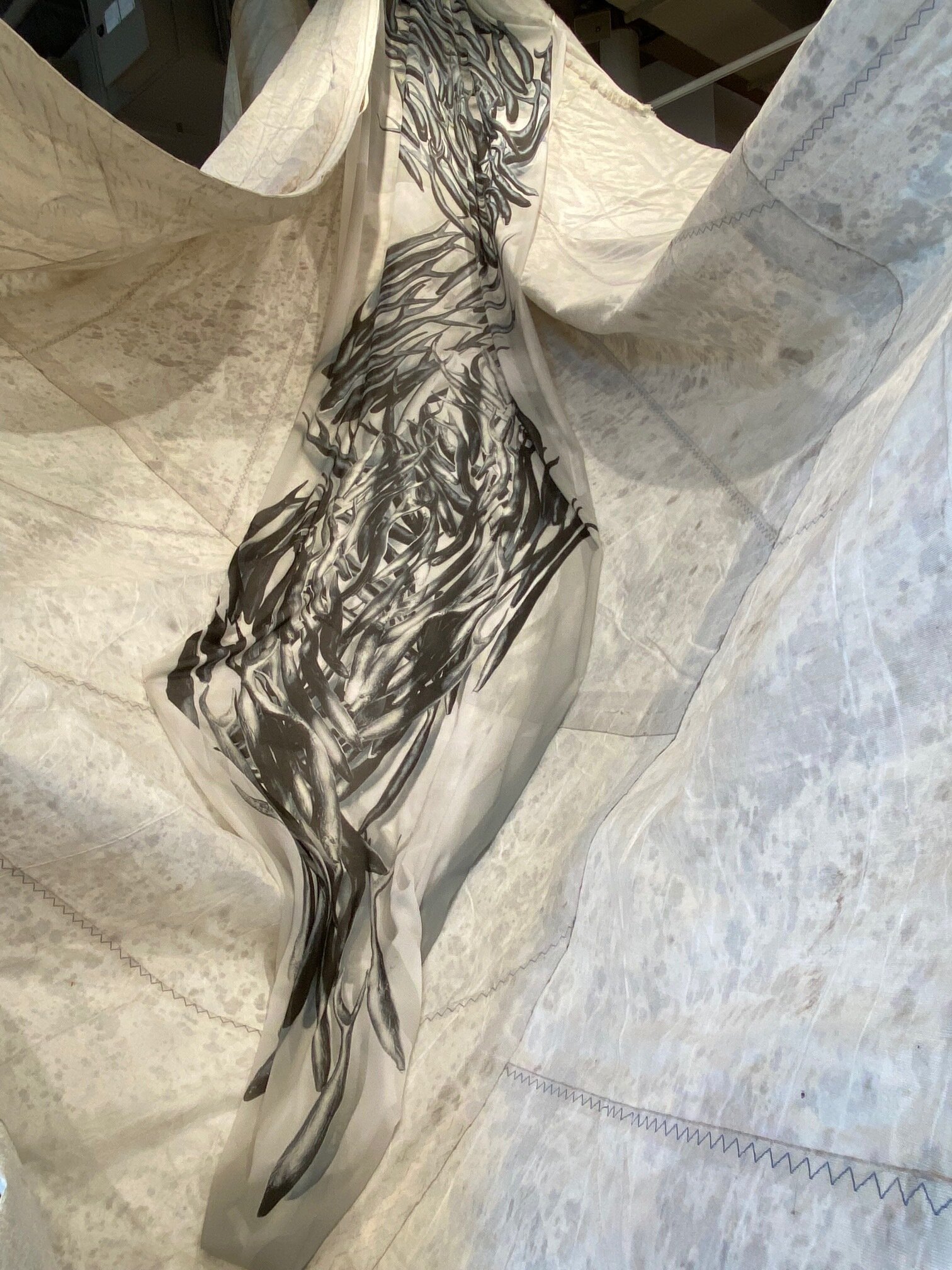

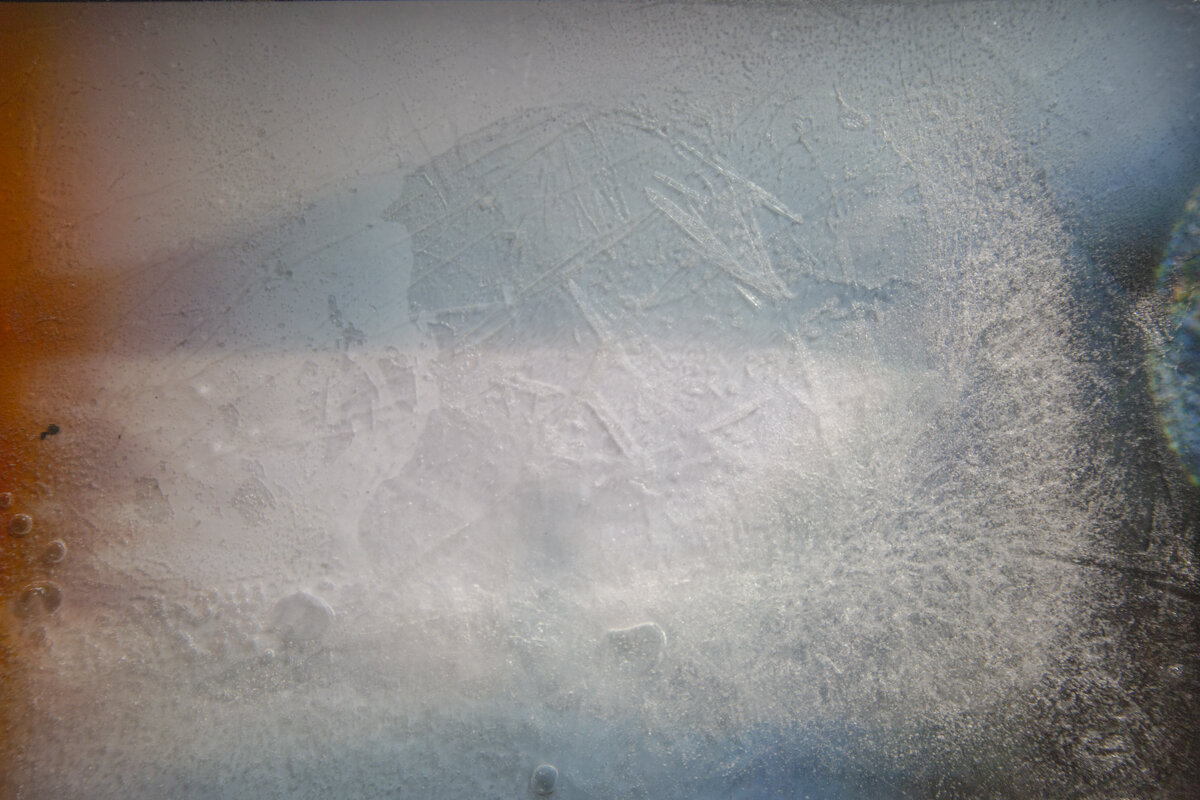

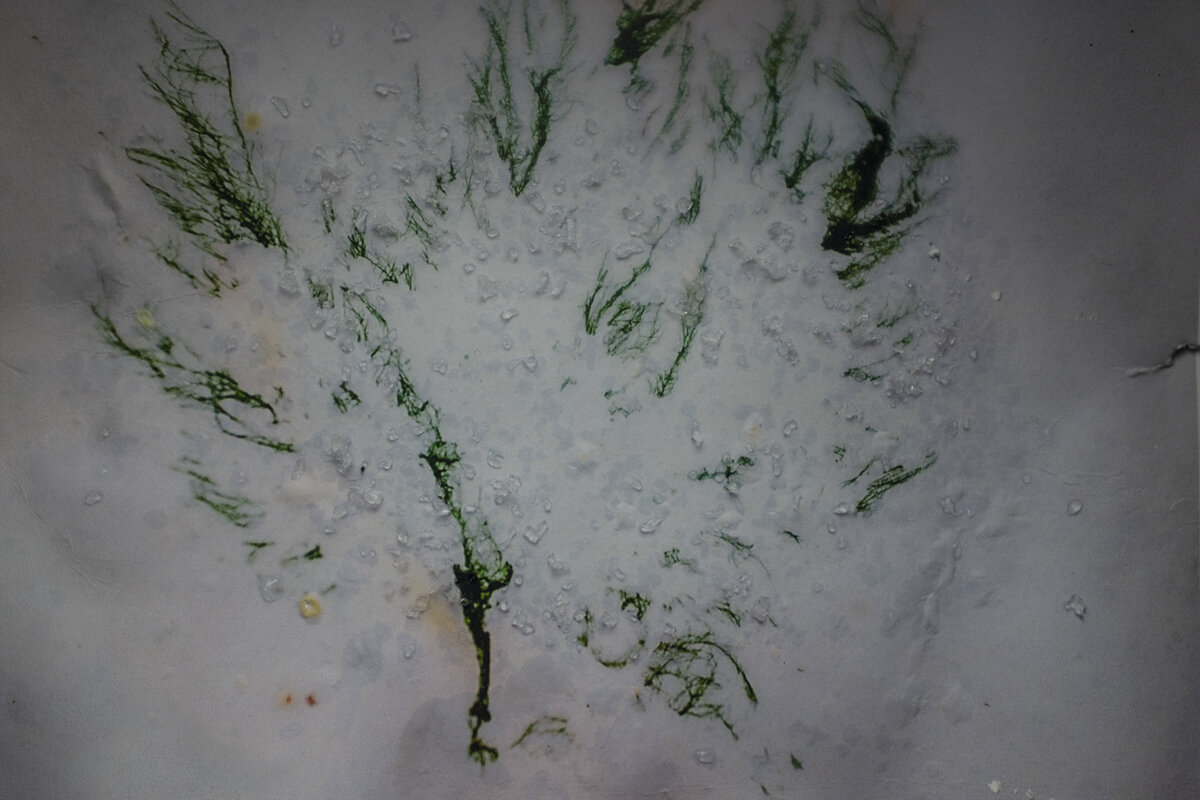

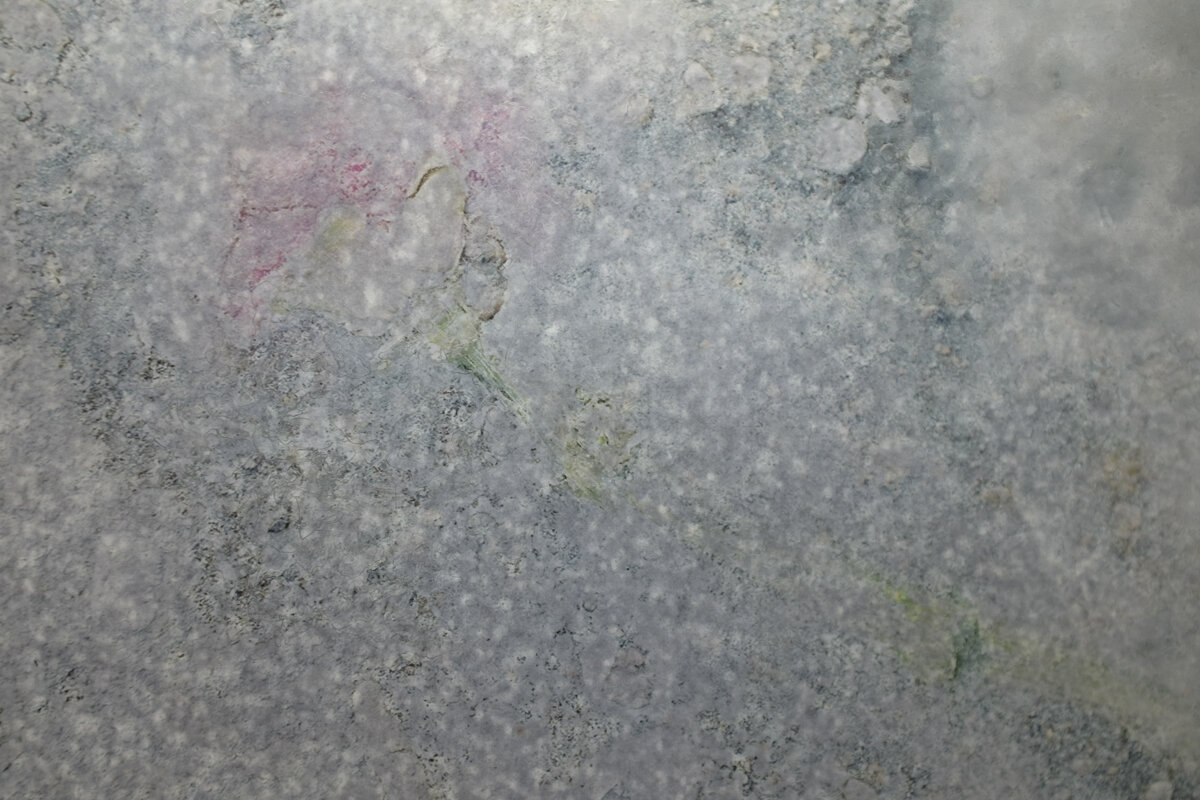

The centerpiece of the exhibition consists of commemorative portraits created using the “anthotype” technique, discovered in the 1840s, in which photographs are created from plant material. Leaves and flowers found at mass killing sites are blended to create an emulsion that is then painted onto art paper. Because the plant material is gathered from the mass grave sites where the bodies of the murdered individuals lie, the final photograph likely contains, at the molecular level, something of his or her remains. The physical trace of these individuals restores their humanity and avoids consigning them to the status of faceless statistics.

The anthotype technique is a meaningful and appropriate way to commemorate those who were lost in the dispersed Holocaust, but it is only useful for commemorating those for whom we have a name and a photograph. And for so many of the victims, we simply don’t have that information. In order to be more inclusive, we were forced to seek out strategies that would better represent all those who lost their lives. Importantly, each one of these strategies is intimately involved with the landscape in which the atrocities occurred.

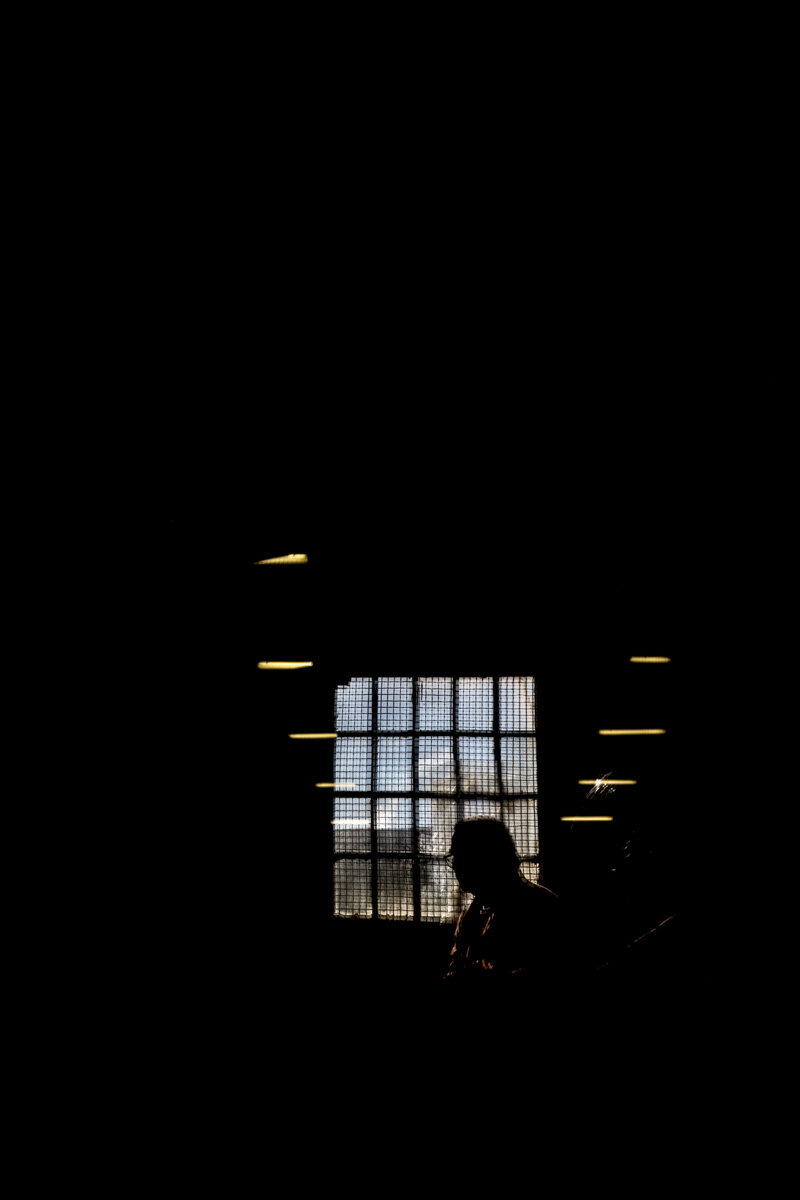

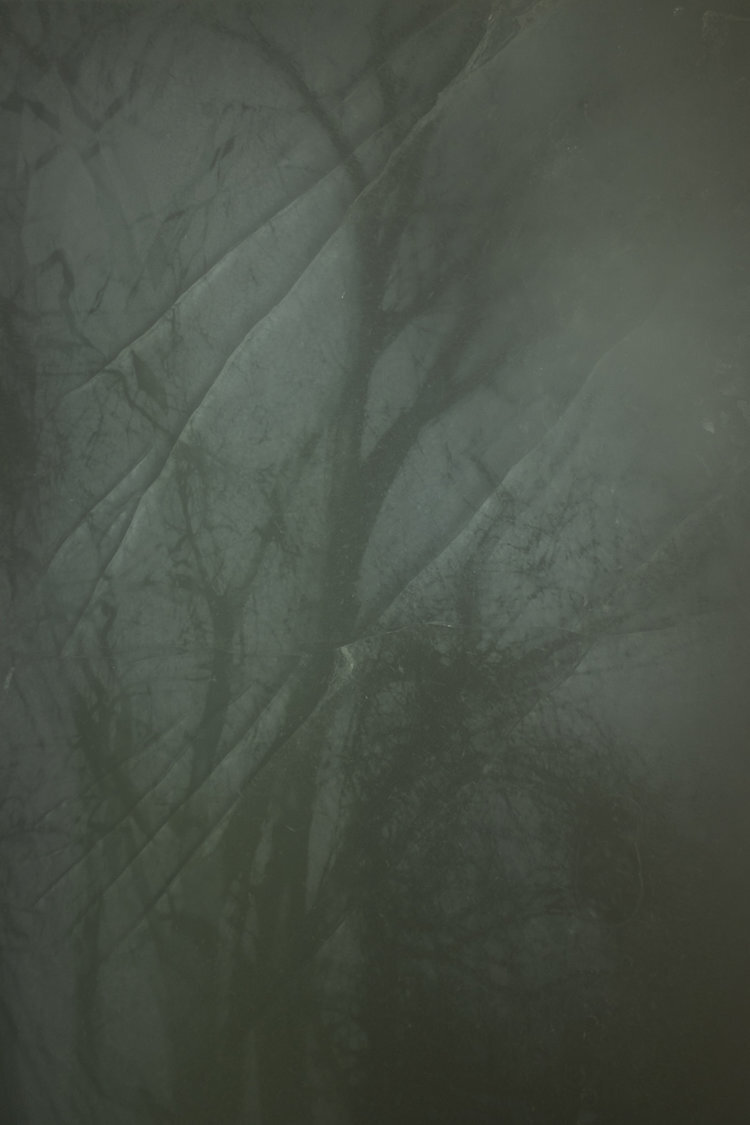

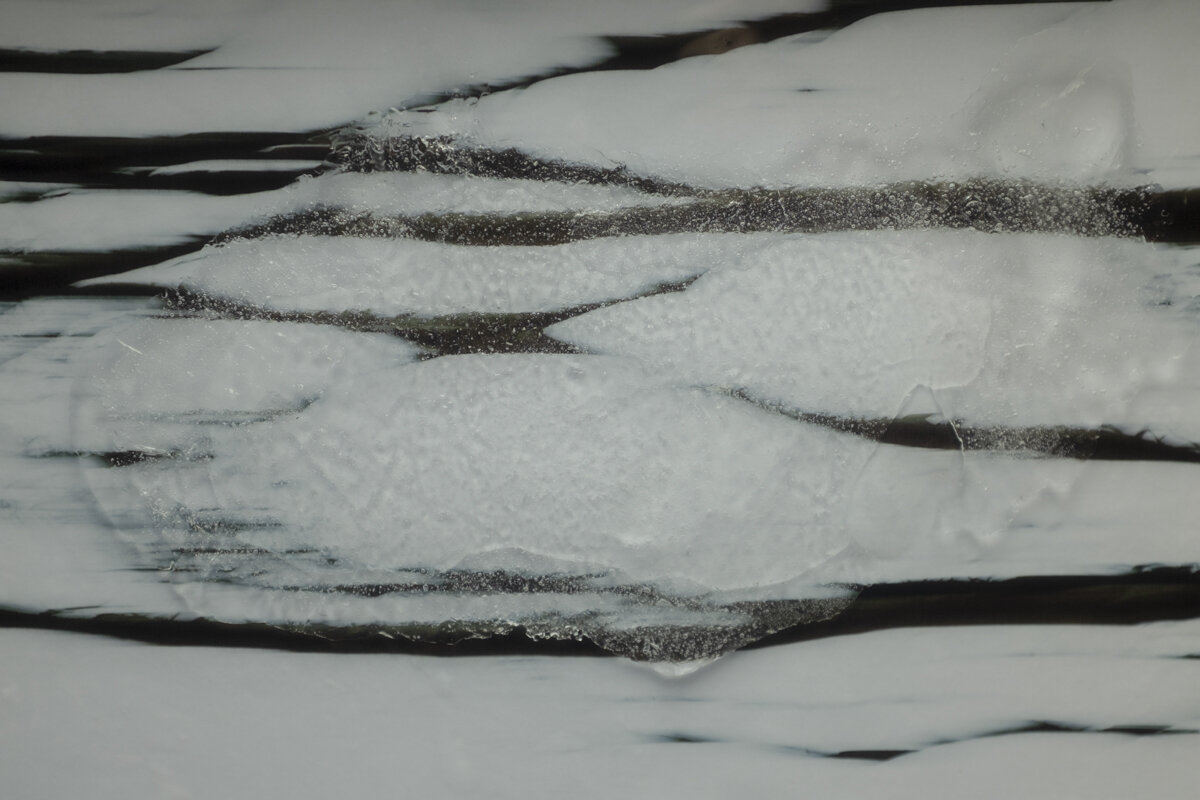

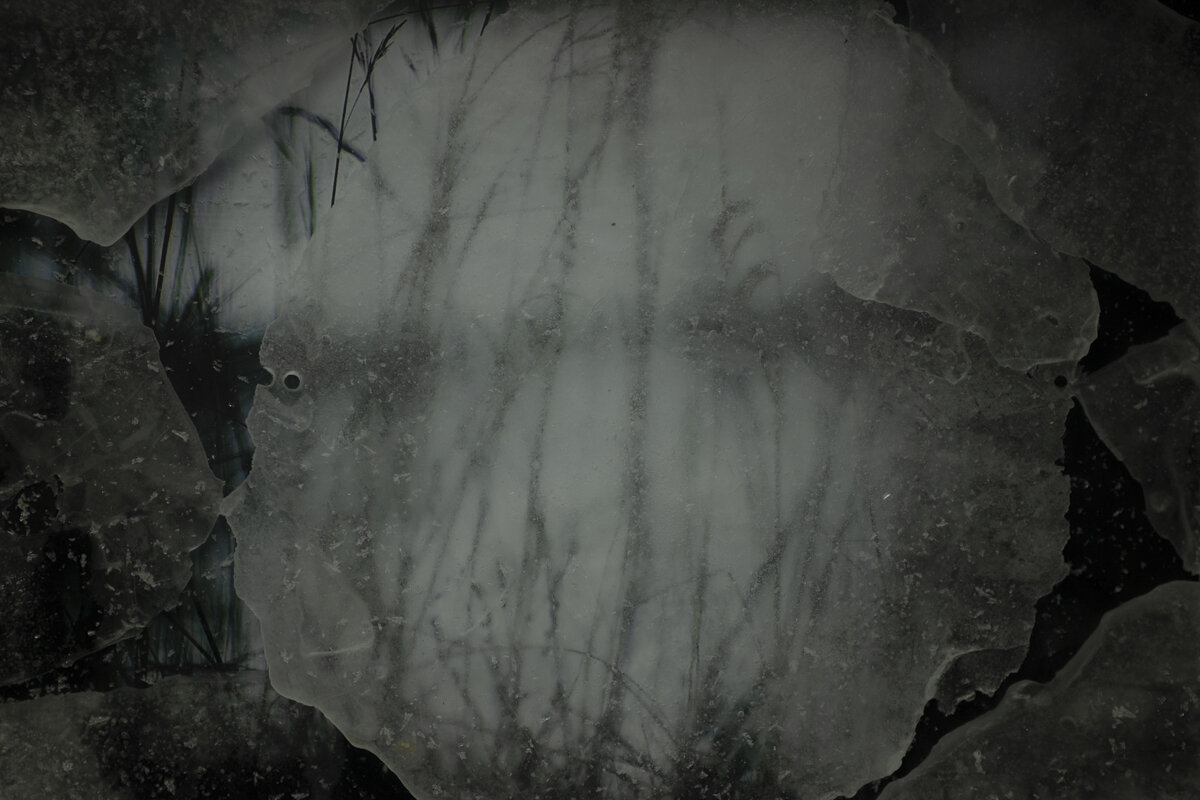

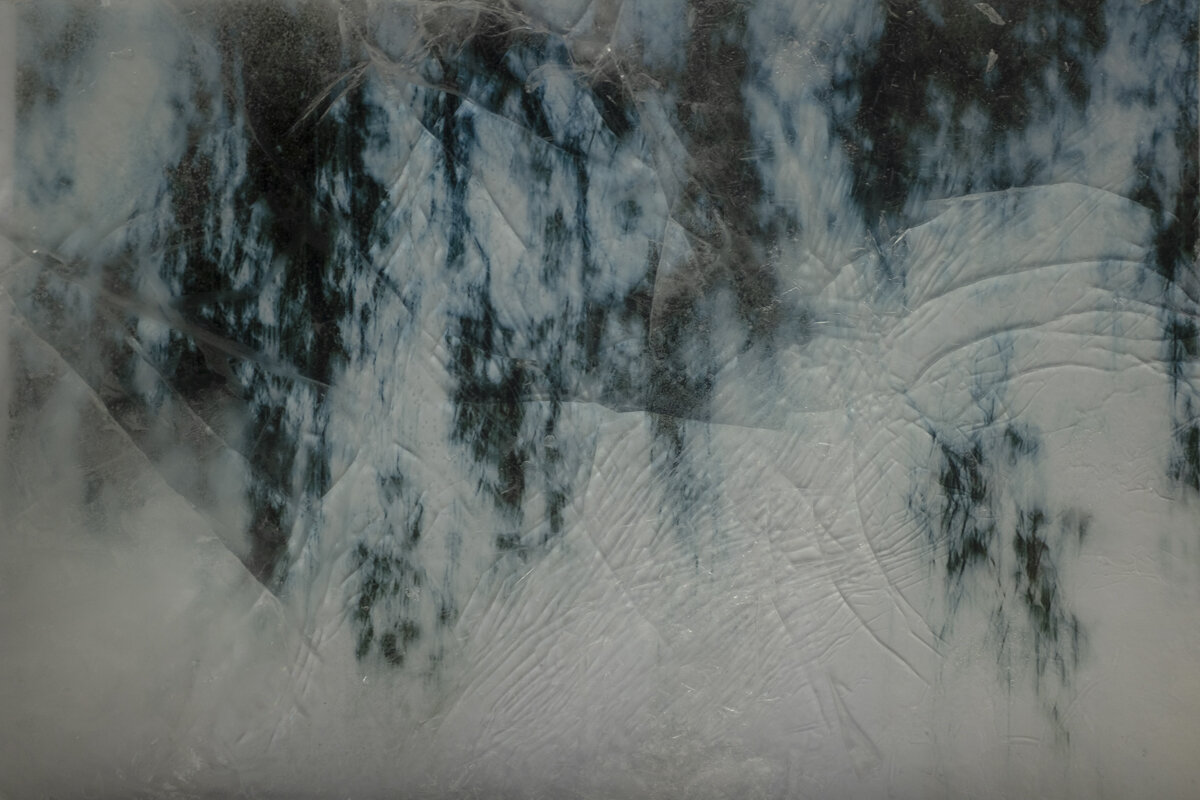

First, we used the concept of witness or living memorial trees. “Witness trees” are those that existed at the time of the Holocaust. “Living memorial trees,” by contrast, grew afterwards. But what they have in common is that all of these trees draw on the soil of the mass killing site and therefore contain the remains of the victims. To represent these trees, we used a WWII-era analog camera to make stark, black-and-white silhouettes of these trees that rise out of the darkness into the light, as if striving for truth and justice. The images are collaged in a manner that suggests the fragmentation of our memory.

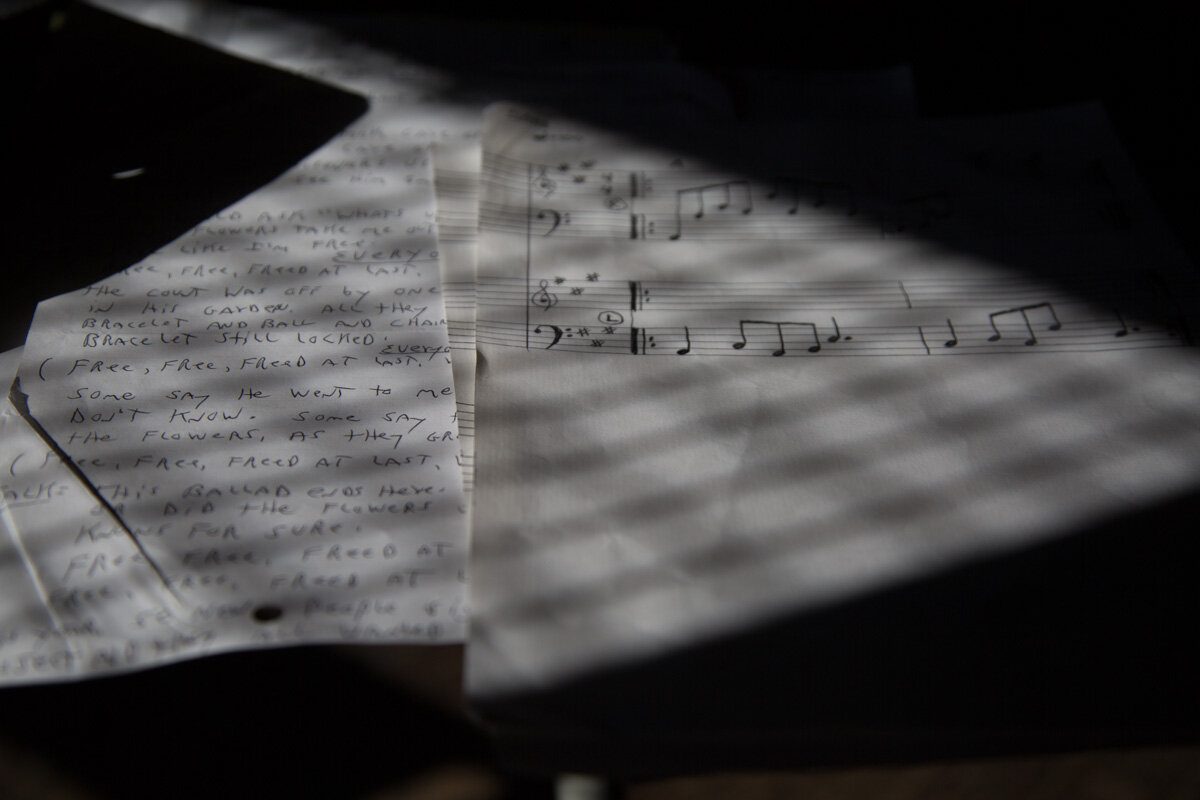

Then we took the focus on witness and living memorial trees a step further. We used a special contact microphone to listen to the interior sounds of these witness and living memorial trees. We think of these sounds, which are not usually heard by humans, as a form of testimony by these trees.

We also used several other alternative techniques to commemorate those who were lost, including watergrams, lumen prints, and a video and sound installation. You can find more information about each of these processes on our website.

Because of its focus on the landscape, the project has an important ecological sensibility. It also begins to point to the connections between genocide and ecocide. Many leading academics studying these topics believe we must consider them together, since they often occur hand-in-hand.

At the opening in Sejny, we urged everyone to remember that the history of the dispersed holocaust is a living history. Mass killing sites are still being discovered today in Poland. And we only need to look at neighboring Ukraine to understand that genocide and ecocide are very contemporary issues. We concluded by emphasizing that we all have a responsibility to seek the truth, pursue justice, and ultimately achieve reconciliation.

Afterwards, one attendee immediately pressed us on what she considered the most important question of all: “What about human nature?” After all, she made clear, war and suffering continue around the globe, including Gaza. In stepped our translator, the wonderful Marci Shore. And she responded by describing the Order of the Teaspoon, an original creation of the author Amos Oz. In his book, How to Cure a Fanatic, Marci explained, Oz wrote the following lines:

I believe that if one person is watching a huge calamity, let’s say a conflagration, a fire, there are always three principal options.

1. Run away, as far away and as fast as you can and let those who cannot run burn.

2. Write a very angry letter to the editor of your paper demanding that the responsible people be removed from office with disgrace. Or, for that matter, launch a demonstration.

3. Bring a bucket of water and throw it on the fire, and if you don’t have a bucket, bring a glass, and if you don’t have a glass, use a teaspoon, everyone has a teaspoon. And yes, I know a teaspoon is little and the fire is huge but there are millions of us and each one of us has a teaspoon. Now I would like to establish the Order of the Teaspoon. People who share my attitude, not the run away attitude, or the letter attitude, but the teaspoon attitude – I would like them to walk around wearing a little teaspoon on the lapel of their jackets, so that we know that we are in the same movement, in the same brotherhood, in the same order, The Order of the Teaspoon.

It’s hard to imagine a better way of describing our posture toward the world right now. It would be dishonest to say that we are optimistic about the future, but at the same time, we feel there is both an urgency and a beauty in continuing to pursue meaningful change. The Order of the Teaspoon appropriately acknowledges that our solitary selves are relatively helpless against the onslaught. But millions of teaspoons may very well start to make a difference, even against a very large fire.

The Borderland Foundation, and other efforts like it around the world, are making a push in this direction, and we are proud to be in their company. Yes, we do face a complex “polycrisis,” with interconnected problems that have the potential to be catastrophic, as the historian Adam Tooze has made clear. Nevertheless, we find solace in his dark humor: “It may be a tightrope walk without an end,” he warns. “But at least we don’t walk it alone!”