Jessica Zychowicz

This is the third of four in a series of experimental poems by Jessica Zychowicz, a scholar, critic, curator, and writer currently based at the University of Alberta's Contemporary Ukraine Studies Program in Canada. The title of the series, "Workshop for the Revolutionary Word," references the avant-garde circles of artists in Kyiv, Ukraine, in the 1920s, a context that gave rise to fierce debates on the direction of culture between opposing groups of writers in the early Soviet era. The poet Mykola Khvylovy, first a member of the Ukrainian Communist Party CP(B)U organization Hart, later founded VAPLITE in 1925 (Vilna Akademiia Proletarskoi Literatury—The Free Academy of Proletarian Literature) that served as a powerful platform for his critiques. He disagreed with Rosa Luxemburg and her Ukrainian supporters Iurii Piatakov and Evgeniia Bosh, who claimed that the world transformations then occurring were successfully dissolving national boundaries; by contrast, he put forward that any conclusion to the search for a more revolutionary, more progressive internationalism had yet to be achieved. “To create a new language Khvylovy fused various linguistic levels: the traditional concerns of the Ukrainian intelligentsia were interspersed with references to Western literature, Marxist political theory, the macaronic language of the Russian civil service, and the racy idiom of the town proletariat. The twenties were witnessing a democratization of culture of unprecedented proportions: the introduction of mass education, mass publications, radio and cinema meant a rapid expansion of culture beyond lyrical poetry and the theatre of ethnographic realism.” (Shkandrij, Myroslav. Modernists, Marxists, and the Nation: The Ukrainian Literary Discussion of the 1920s. Edmonton: CIUS Press, 1992, p. 55.) Parallels to this earlier moment of social and cultural upheaval in the early Soviet era can be felt and seen in Ukraine today. These poems bring together contemporaneous observations in the frame of exploring forms of dissent with regimes of power around the globe that serve to oppress creative expression. Asking us to revisit what can so easily be taken-for-granted, or rendered invisible, the poems play with historical repetition in different times and places in order to unmask “new” versus “old” technologies of censorship. These poems are shared in keeping with Atlantika Collective's emphasis on embracing an "open circle" of artists, writers, curators, educators and thinkers. Jessica welcomes any responses in this collaborative spirit. For more on Jessica's background, please visit our Members and Contributors page.

WHERE THE FUTURE IS

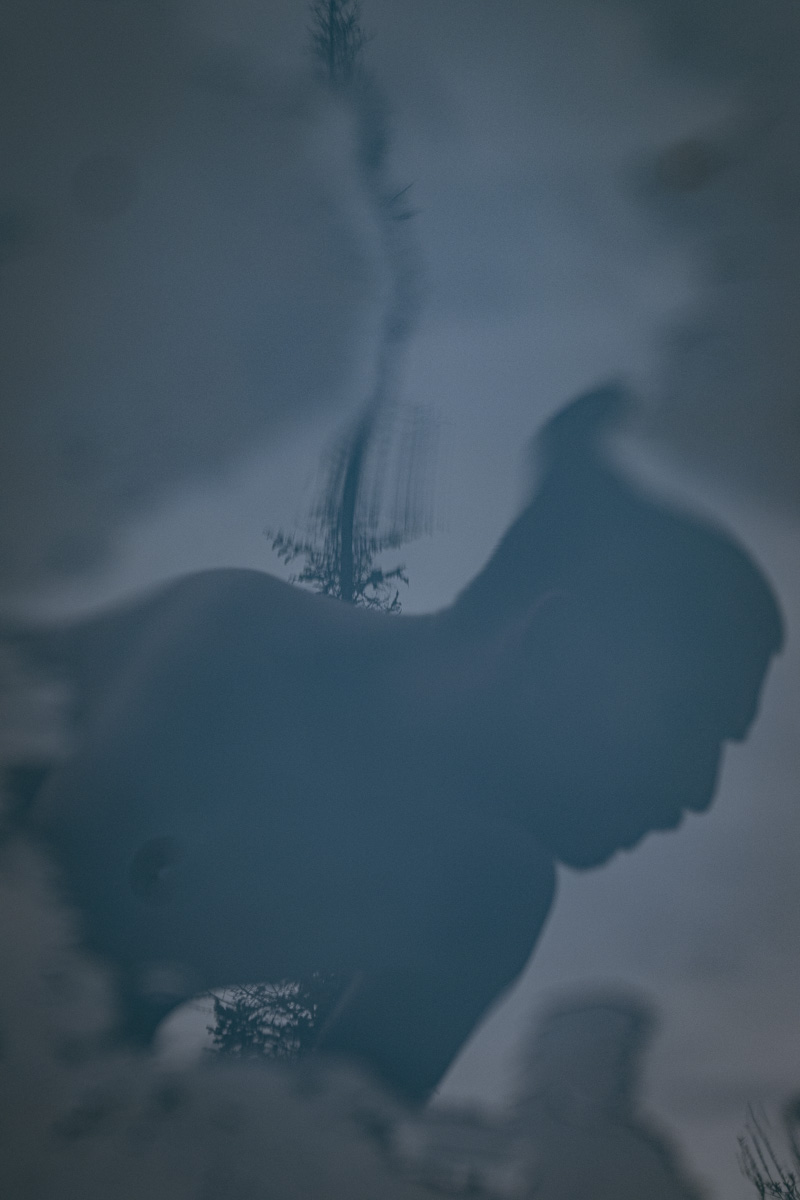

UKRAINE is a country

Of angels and mafia men,

Of gunshots and gunned engines,

gutter dogs and little girls in

thick striped tights waiting to take communion.

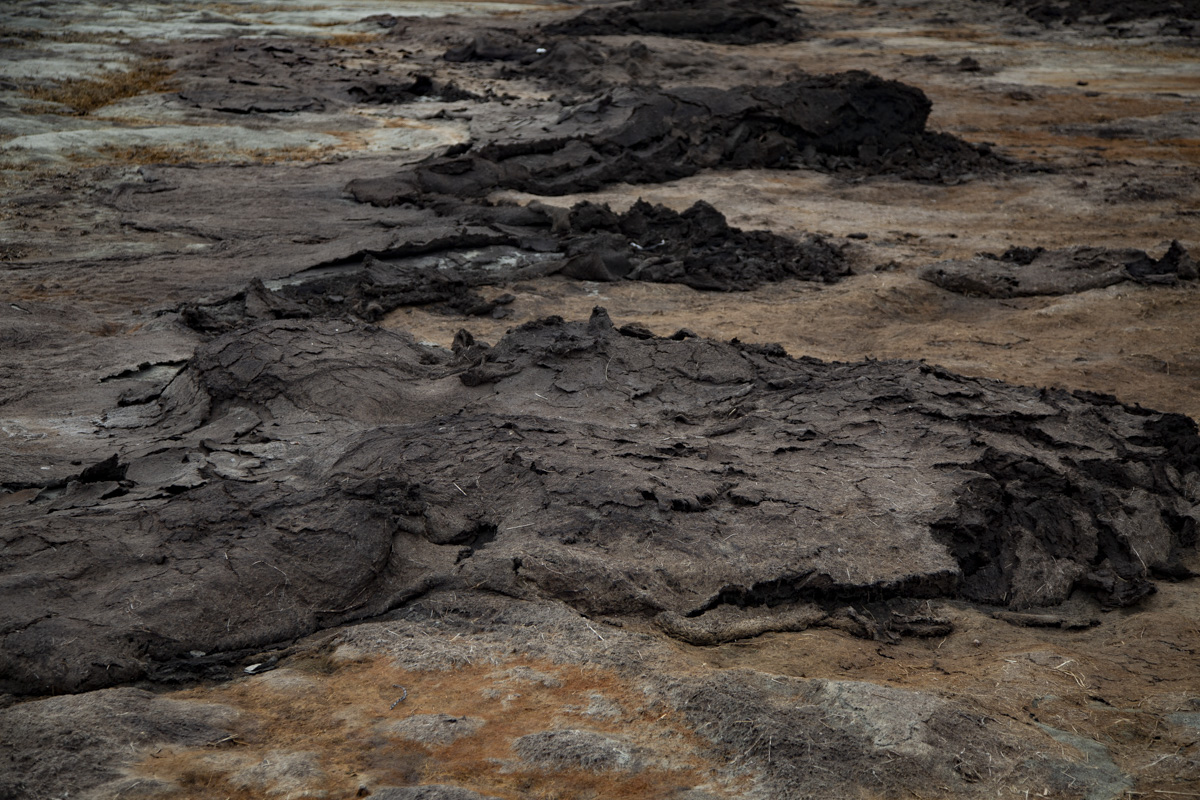

Ukraine survives on its soiled hands,

on its gritty shell,

on its back like a COCKROACH—it kicks hard with a powerful will.

Ukraine is a territory claimed by

its neighbors’ tendencies to EXPAND,

and machines that SPIT AND CUT,

hurtling tons of wheat across 50 GAUGE RAILS well past midnight.

And they keep the EVIDENCE of DECADENCE anyway—

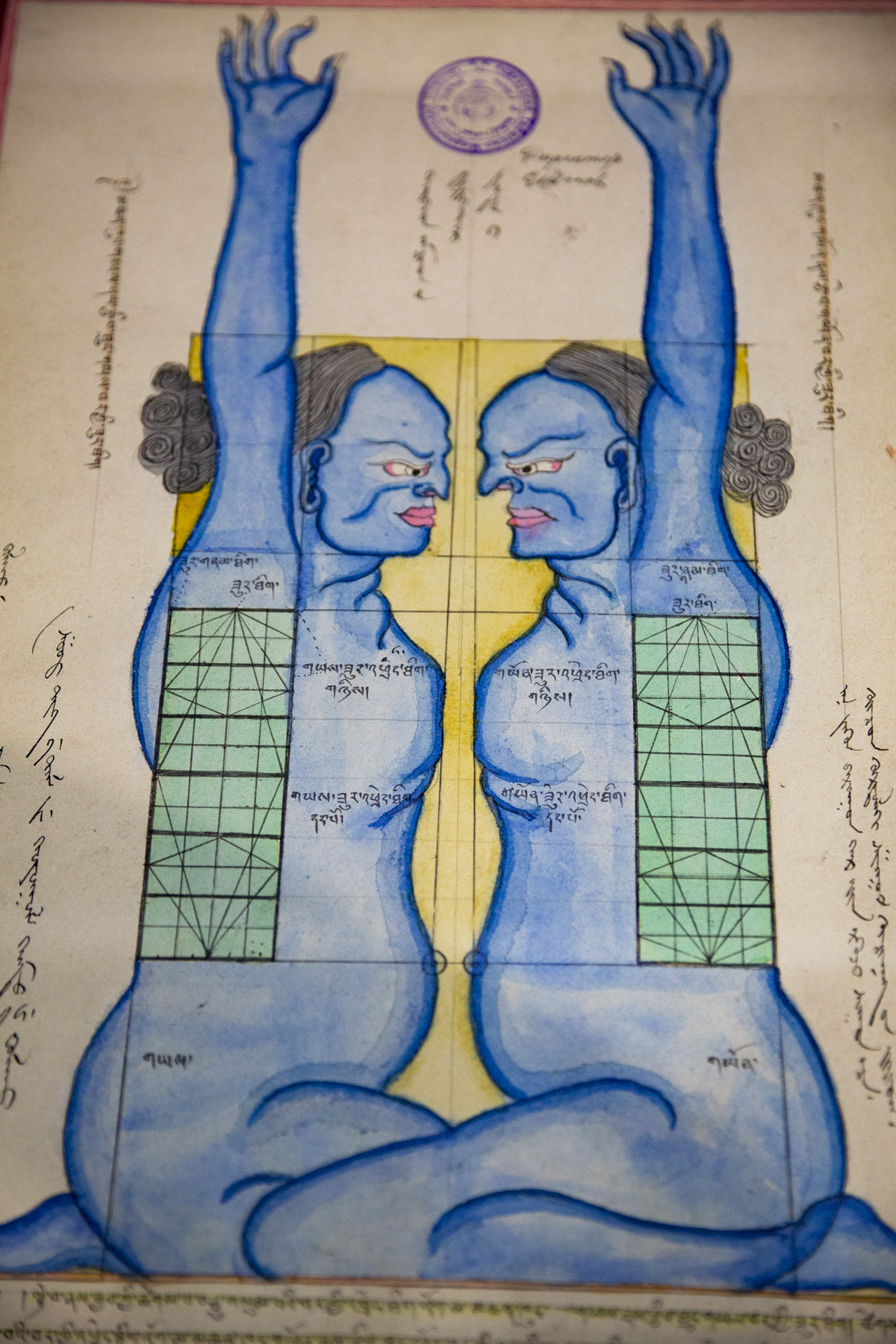

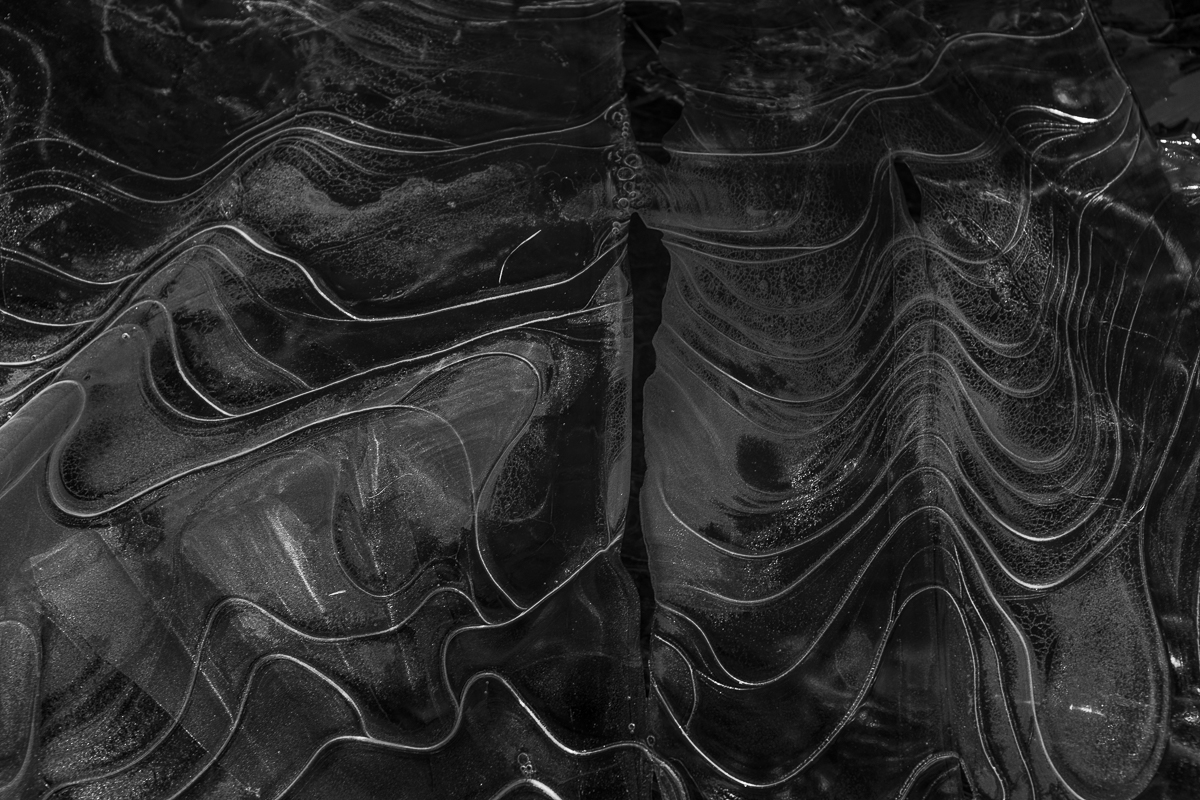

the SOVIET crystal decanter CONSTRUCTED from two halves,

two NATIONS ALIKE IN DIGNITY

stamped together in a FACTORY—

the line between them nearly invisible,

but still tactile—perceptible only to the touch

WHERE CIVIL BLOOD MAKES CIVIL HANDS UNCLEAN

walnut whisky running over everything

IN FAIR KYIV WHERE WE LAY OUR SCENE

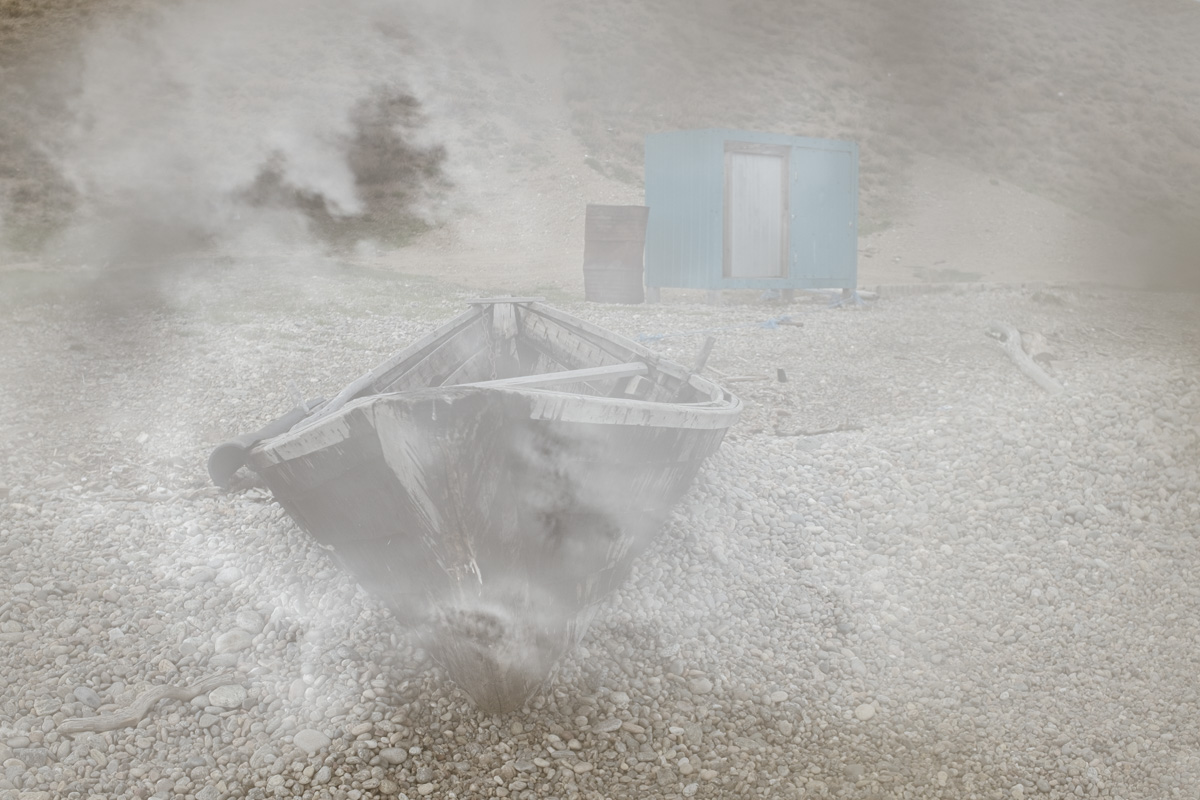

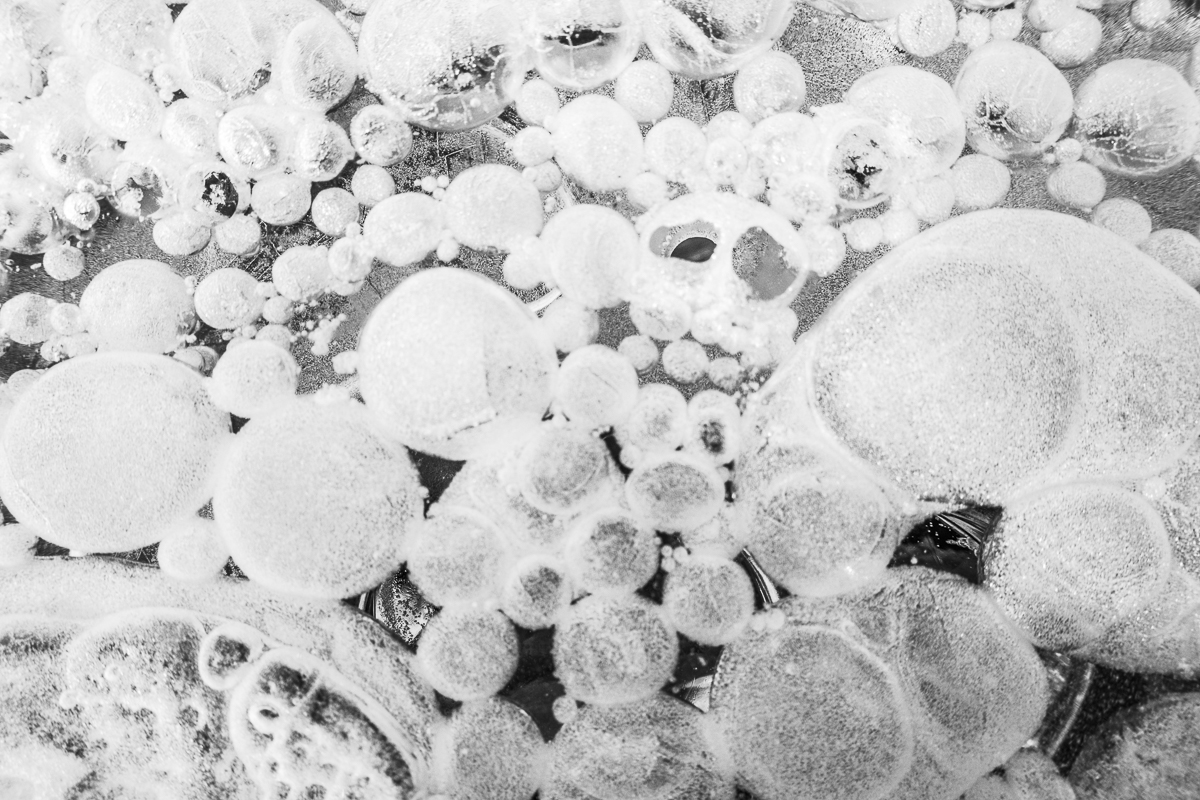

A FLOOD

when they return

to report that they all

PRACTICALLY GOT AWAY WITH MURDER.

STAMPS AND MONUMENTS

will attest that she is an OFFICIAL country—

she is warranted between the lines,

traded in sideways doses of 80 proof currency,

when she deals her CONTRABAND.

POLITICIANS and their HENCHMEN are NO WIT

for the ABACUS

that will eventually serve them up

to the HUNGRIEST WOLF

waiting in line

at the communal counter

O – the inescapability of numbers

and the danger of monthly SPECULATION.

Ukraine is a pot-holed ROAD

A rug on the wall instead of A FLAG

Chicken bouillon, black bread, borscht,

She is one day late in a 24-hour clinic,

a gruff goodbye, a deep bow,

a marriage proposal, an anecdote,

a wooden stool

an “I LOVE YOU” and then a “FUCK YOU”

for believing them, when they say

in the election campaign posters

ON THAT ONE LAST RIDE ON THE METRO

for six Hryvnias instead of eight

that they are all telling the truth

THIS TIME AROUND.

She is a defunct beet SUGAR FACTORY,

Berries that look like eyes, staring,

Out of MANNEQUIN HEADS IN BLACK LACE

An antennae covered in razor wire

REPLAY in the martshrutka rearview.

A clay oven, apologies,

ENVY

and a loud T.V.

tuned to your favorite REALITY SHOW— [INSERT YOUR UTOPIA HERE].

Bring your best CAMERA to capture

TECHNOCHROME FINGERNAILS

and LAMINATED PHOTOS of NEON LUNCH SPECIALS

nothing is too flashy here!

SHE is many headscarves away from THE FRONT LINE,

sitting in the back

OF THE THEATRE

where the bullets sound quieter

AS THEY WHIP BY.

There is also the CHOREOGRAPHY

to consider:

of cherry blossoms during KYIV’S TURKISH TOURIST SEASON

the bills

falling on the bar

faster

than

blouses:

That one tastes of LIPSTICK and the other one is IMITATION PERFUME FROM CHINA.

it must be some strange yeast that they are SELLING here in the bread basket of Europe

where the prices are so cheap, even the INTERNET IS CHEAPER THAN IN PAKISTAN

and don’t have to pay extra

FOR A ROOM WITH A VIEW.

But UKRAINE rides through the winter of her life like an UNBROKEN horse

holding her head up to the LIGHTBULB of a GUERNICA MOON.

IN TORETSK, DONETSK near the city of Konstiantynivka.

they leave potatoes in BLUE BUCKETS for the STRAYS

in the VILLAGE near the train station

to distract themselves from the sound of the GUNS:

“You will OCCUPY NOTHING.”

Then it ends up being the GRIP OF THEIR TEETH,

and not the basket of apples

recorded at the beginning of the FILM REEL

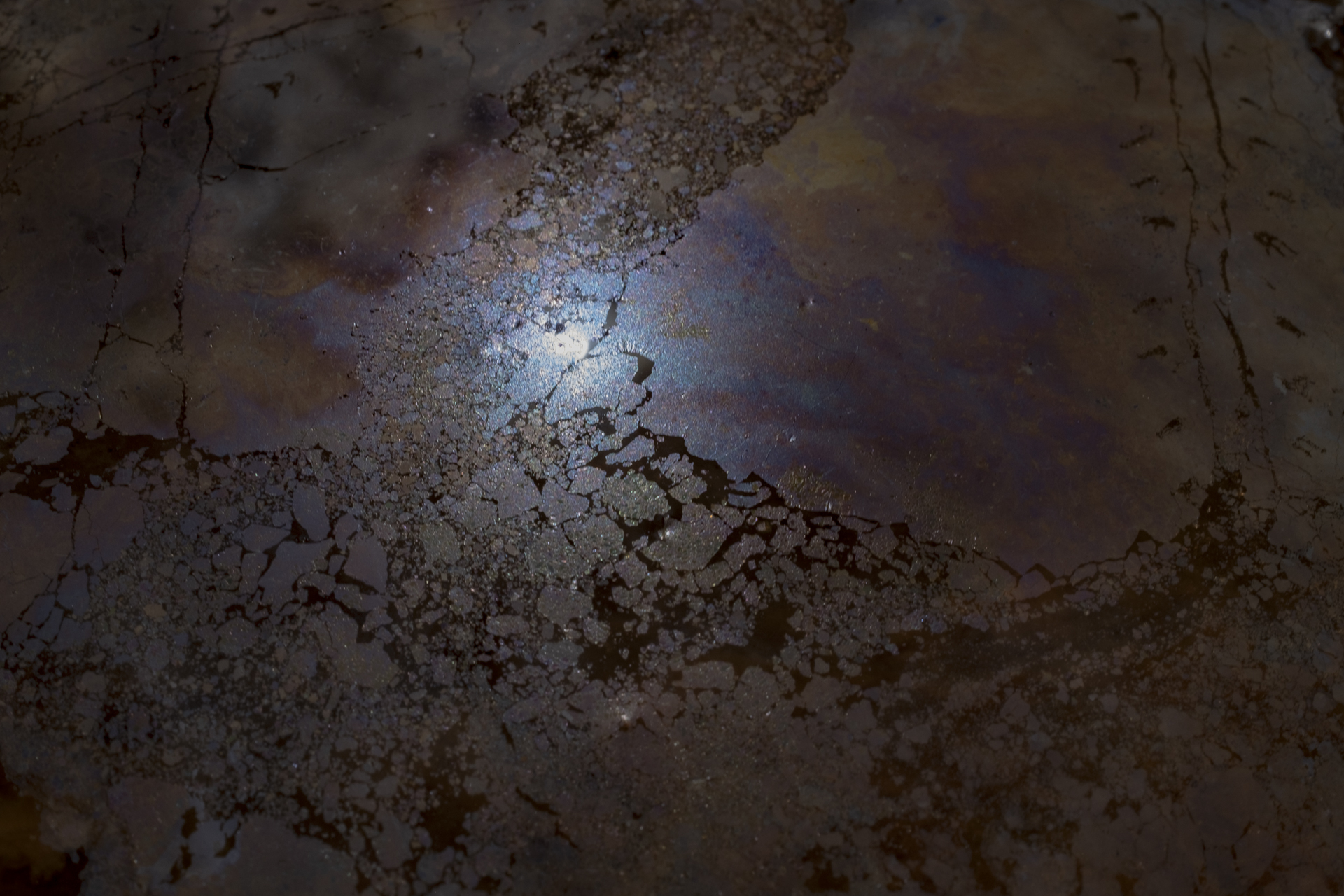

that leaves a purple memory

on her arm.

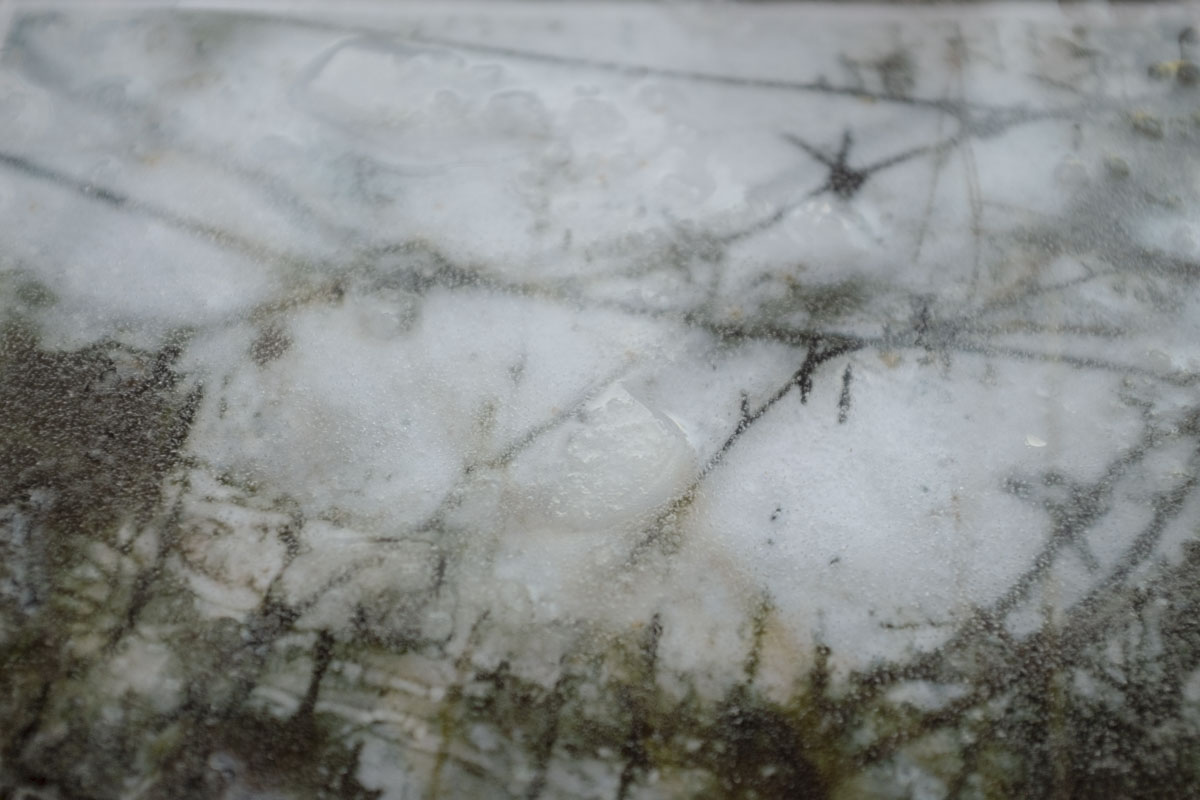

Deep into summer she is bright steel

in the sun’s reflection on her 3,000

riverbeds full of SHRAPNEL

“I dare you!”

Thunder cracks over her back,

BANG! BLAST!

She disappears—

like GOGOL’S DEVILS under lightning.

This is what her villagers will tell you,

when they PREDICT that their crop will turn out.

AND IT DOES.

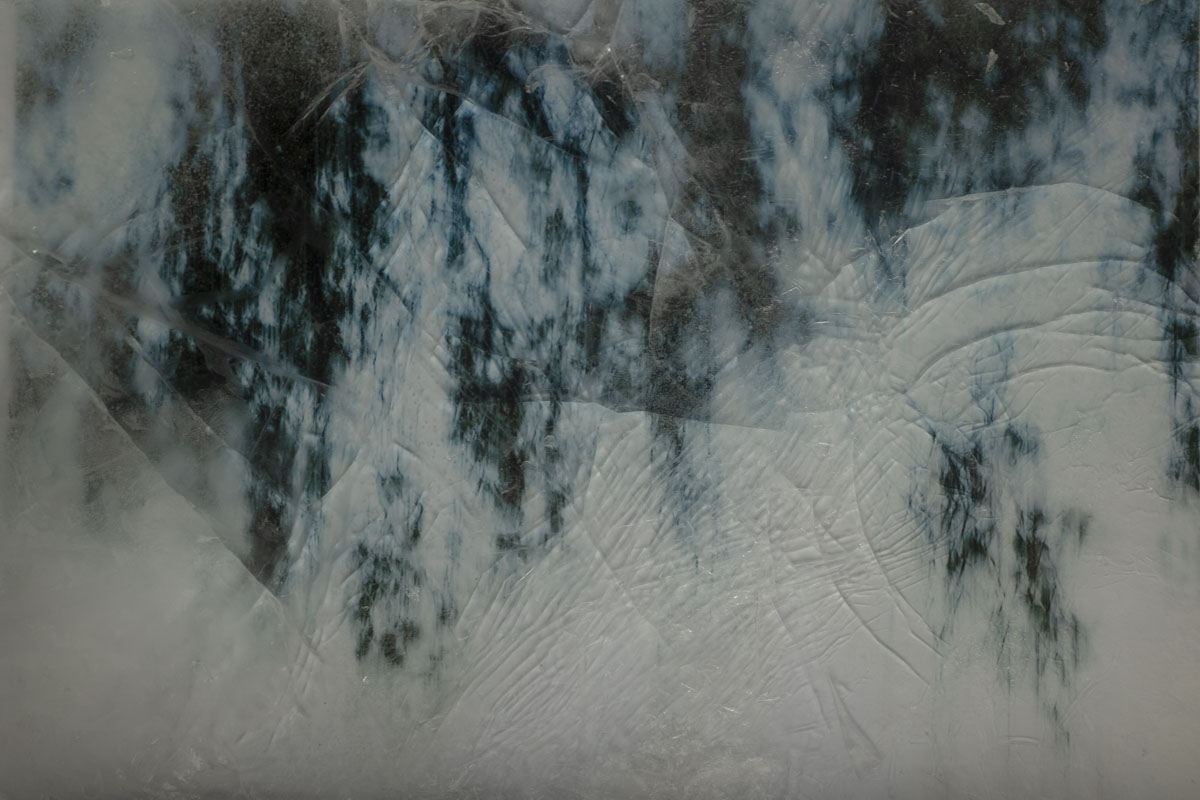

She is RED OCTOBER,

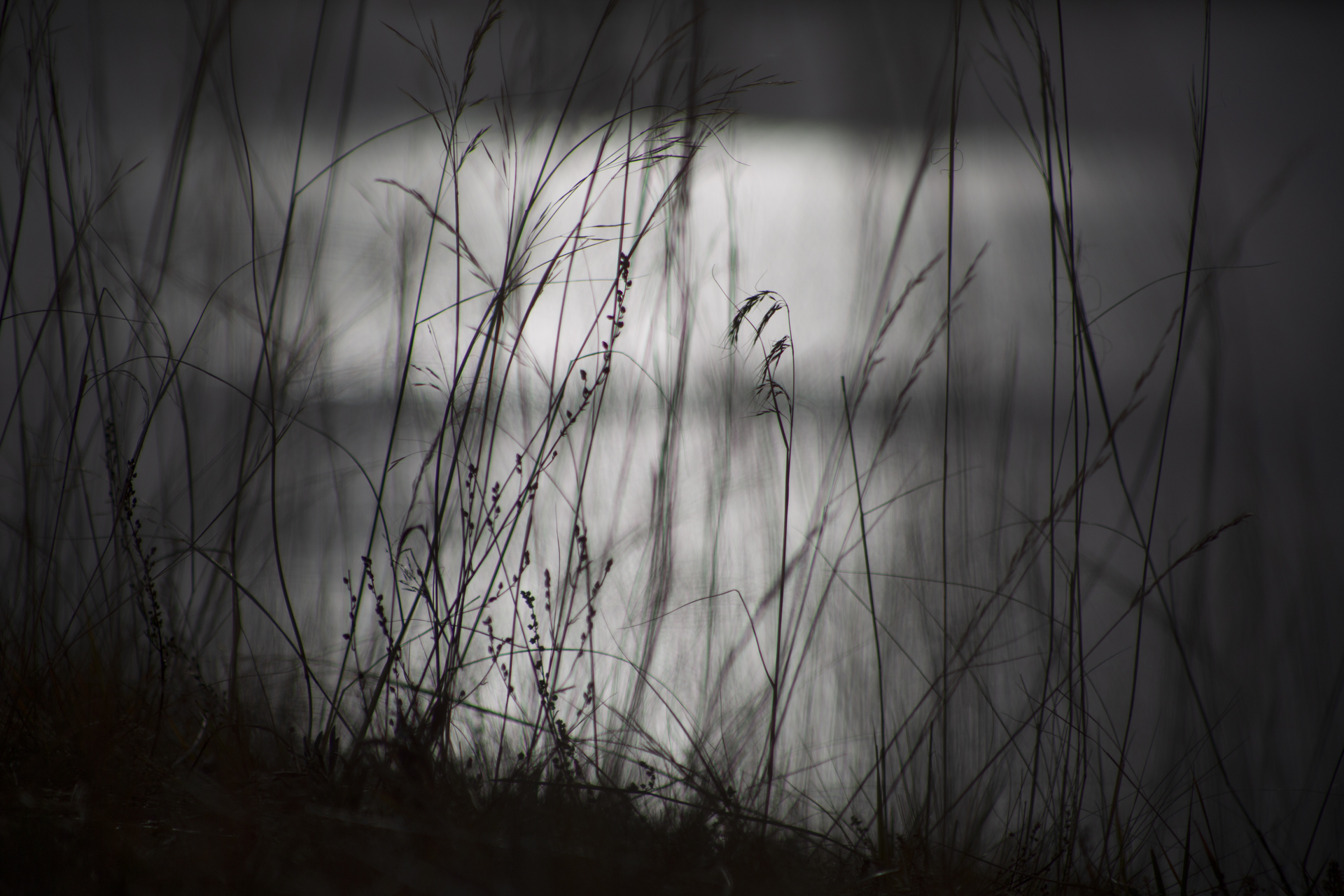

when the silent watchers among the trees give up their currency

and demand another COUNT for the HARVEST

stolen and imprisoned in jars

basements

and MINDS.

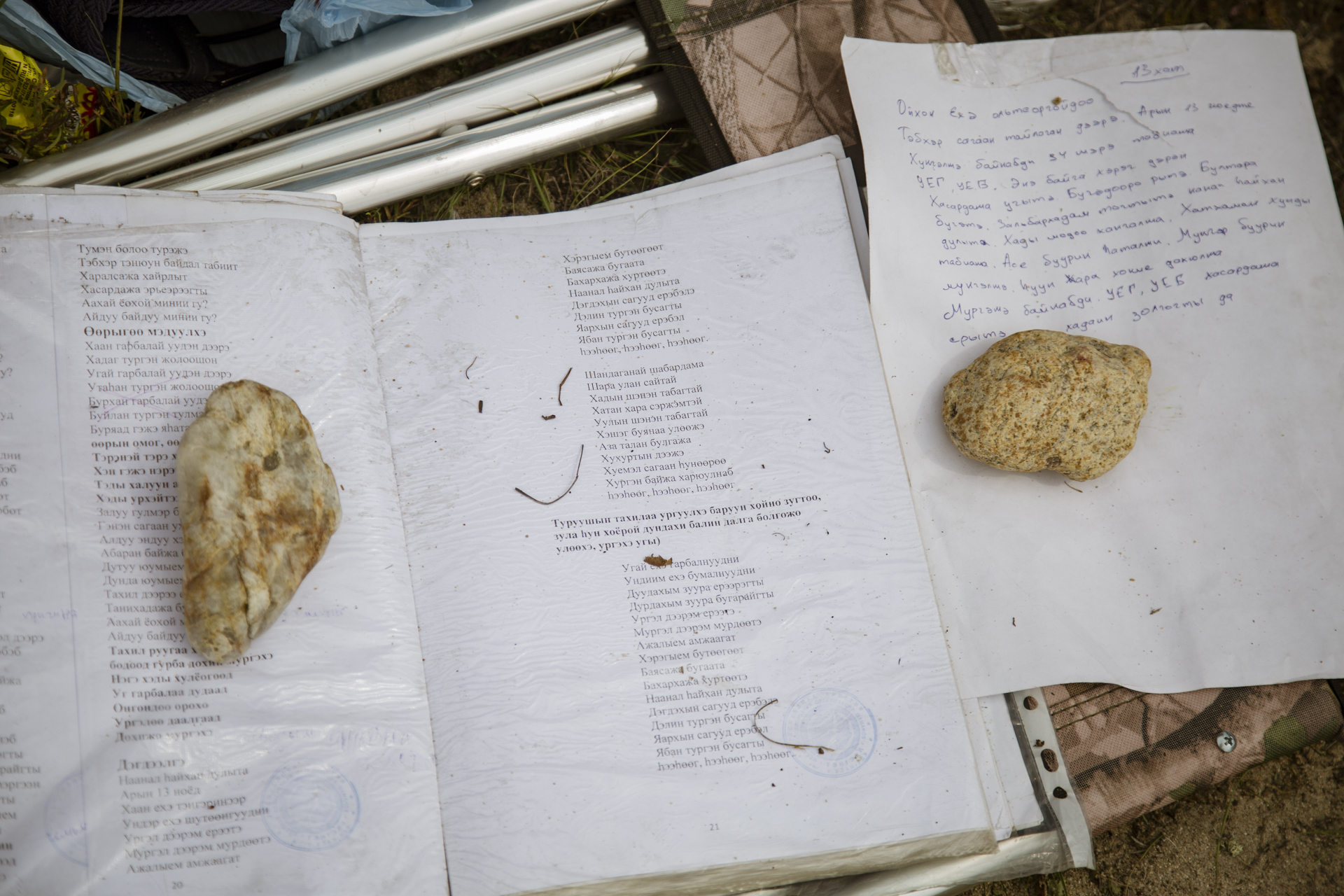

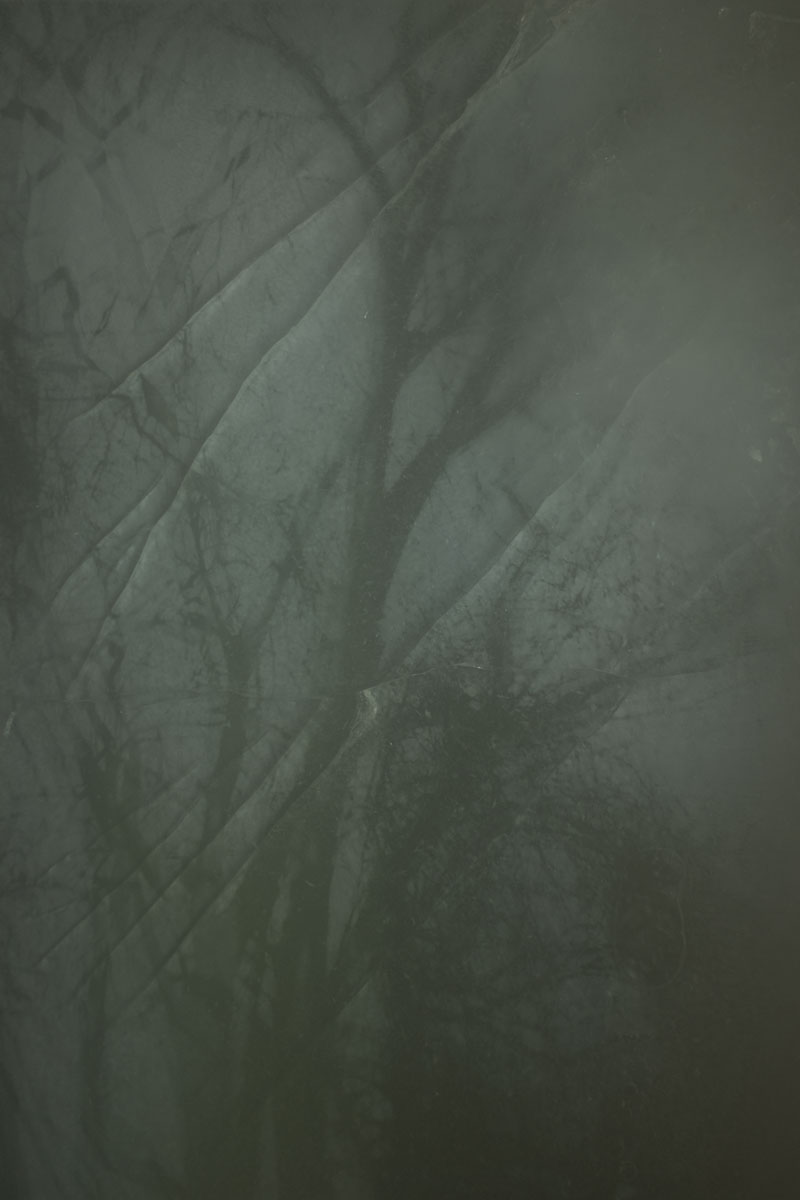

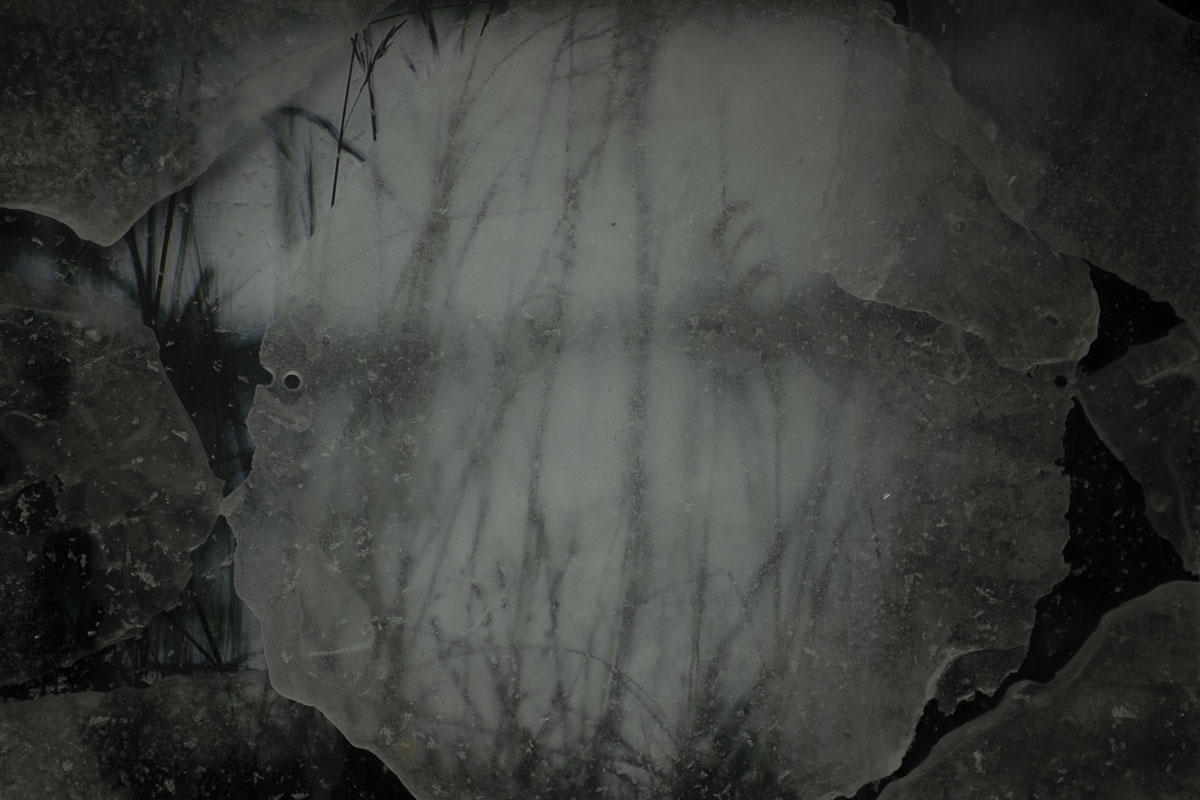

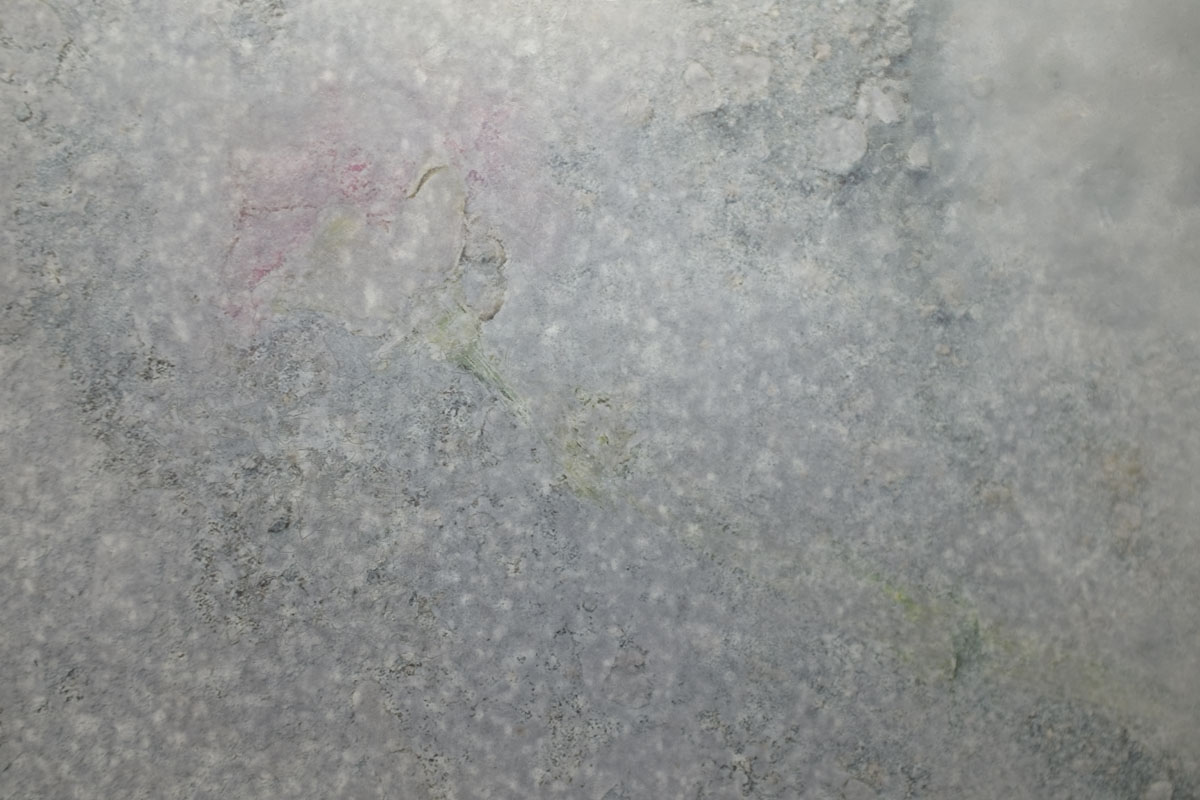

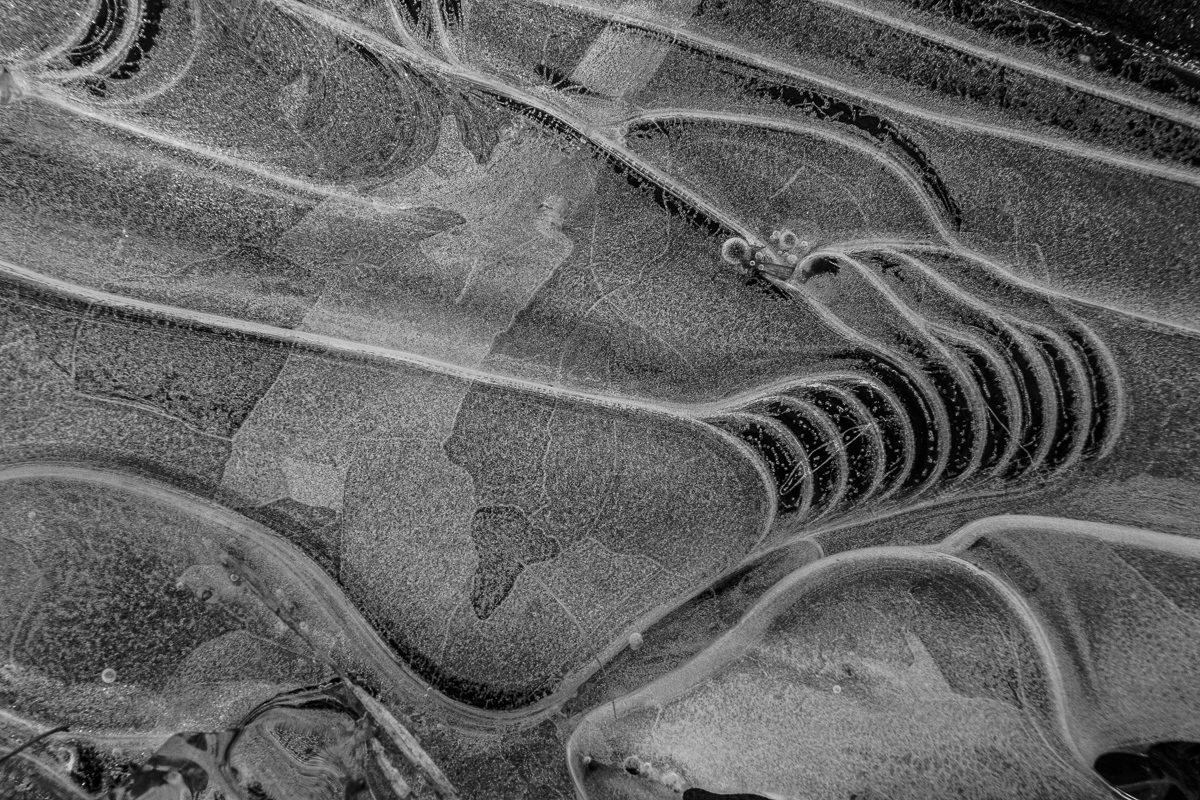

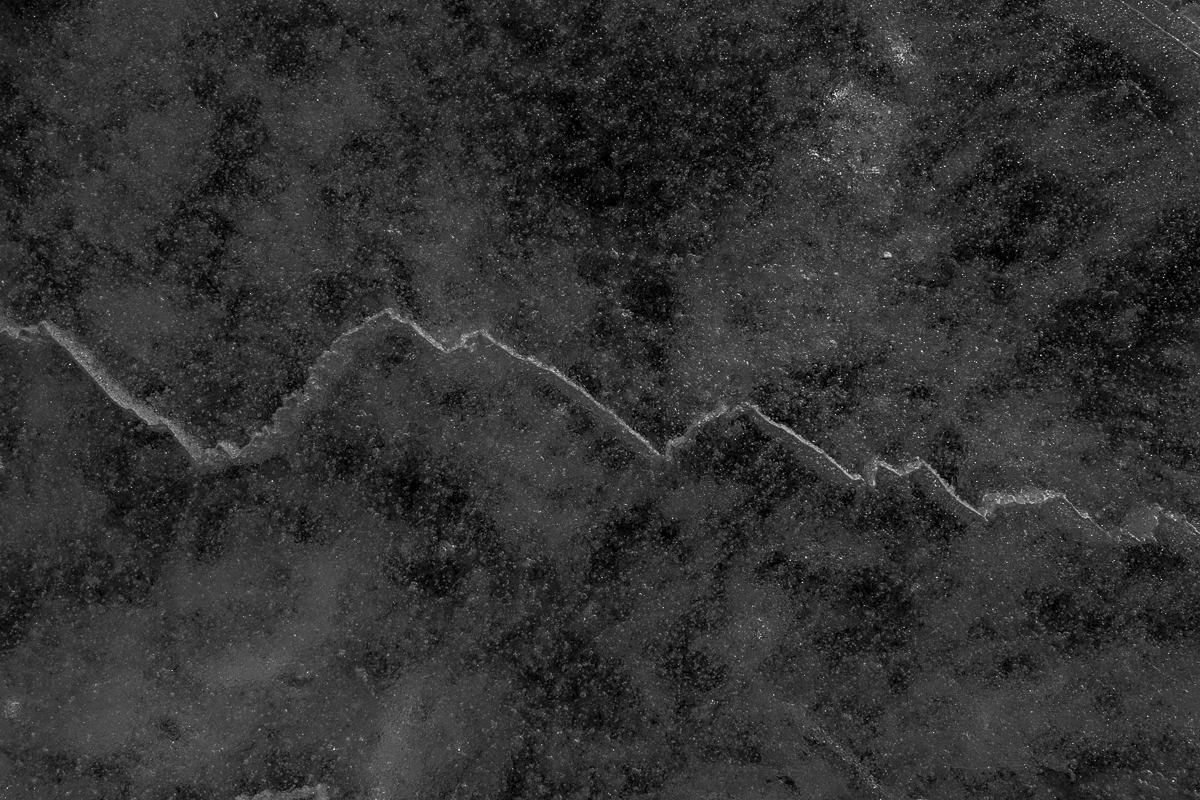

Ukraine is ashen like BURIED BONES and OLD PAPER—

far flung with the distancing effect of

historical documents and crushed snow,

footprints in the catacombs

where SAINTS and SOVIETS STILL ACCUSE each other in the DUST:

A SLAP IN THE FACE OF PUBLIC TASTE!

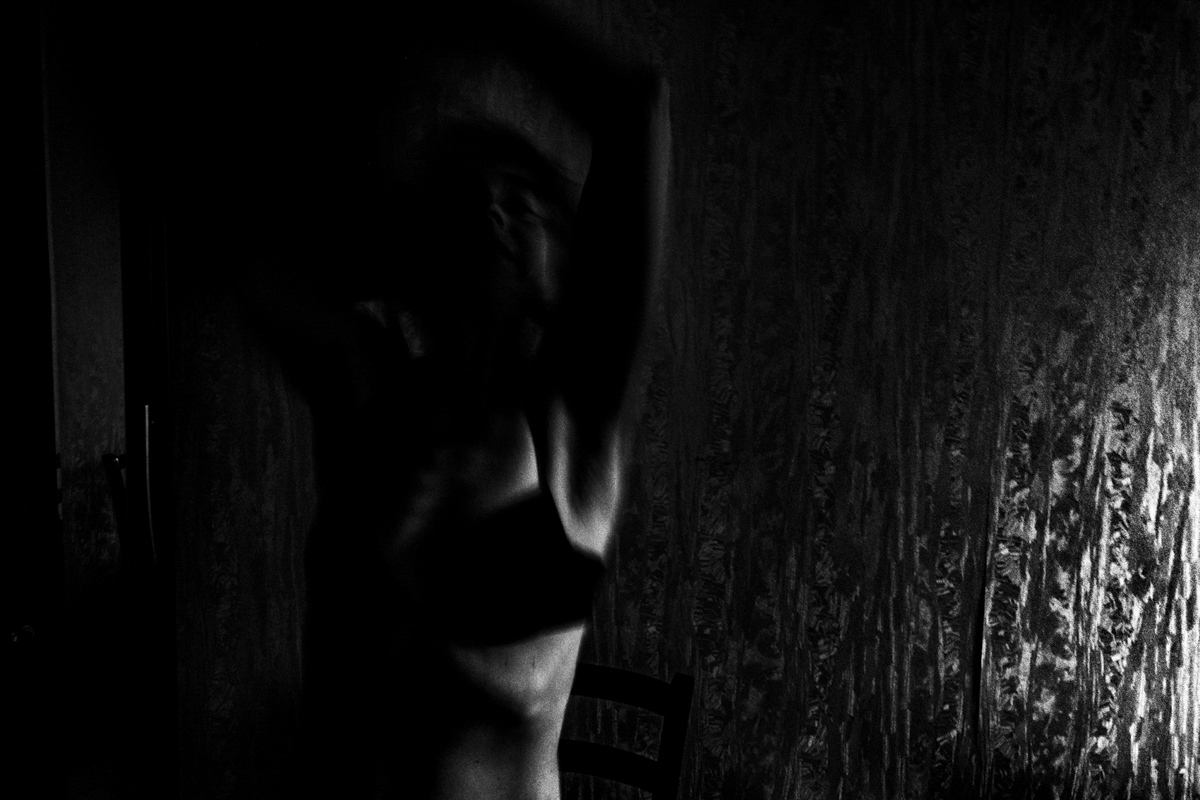

When she has had enough with the FIGHT—

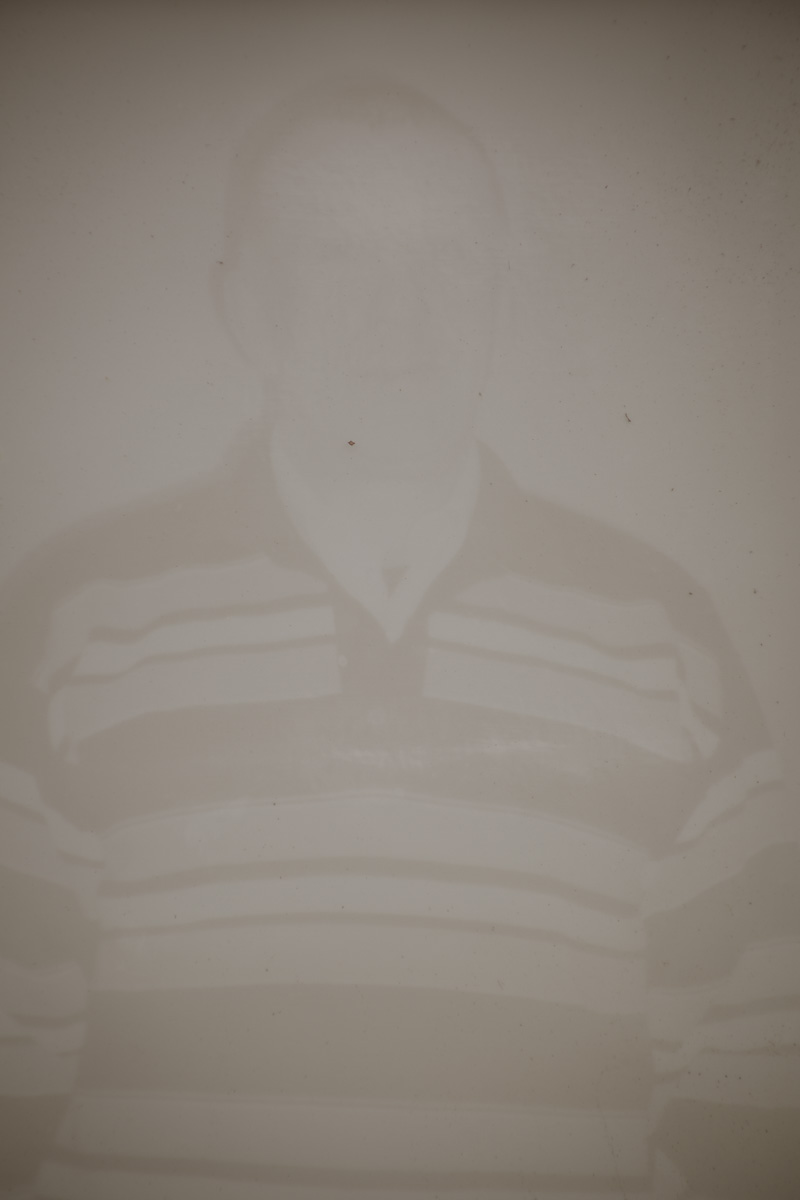

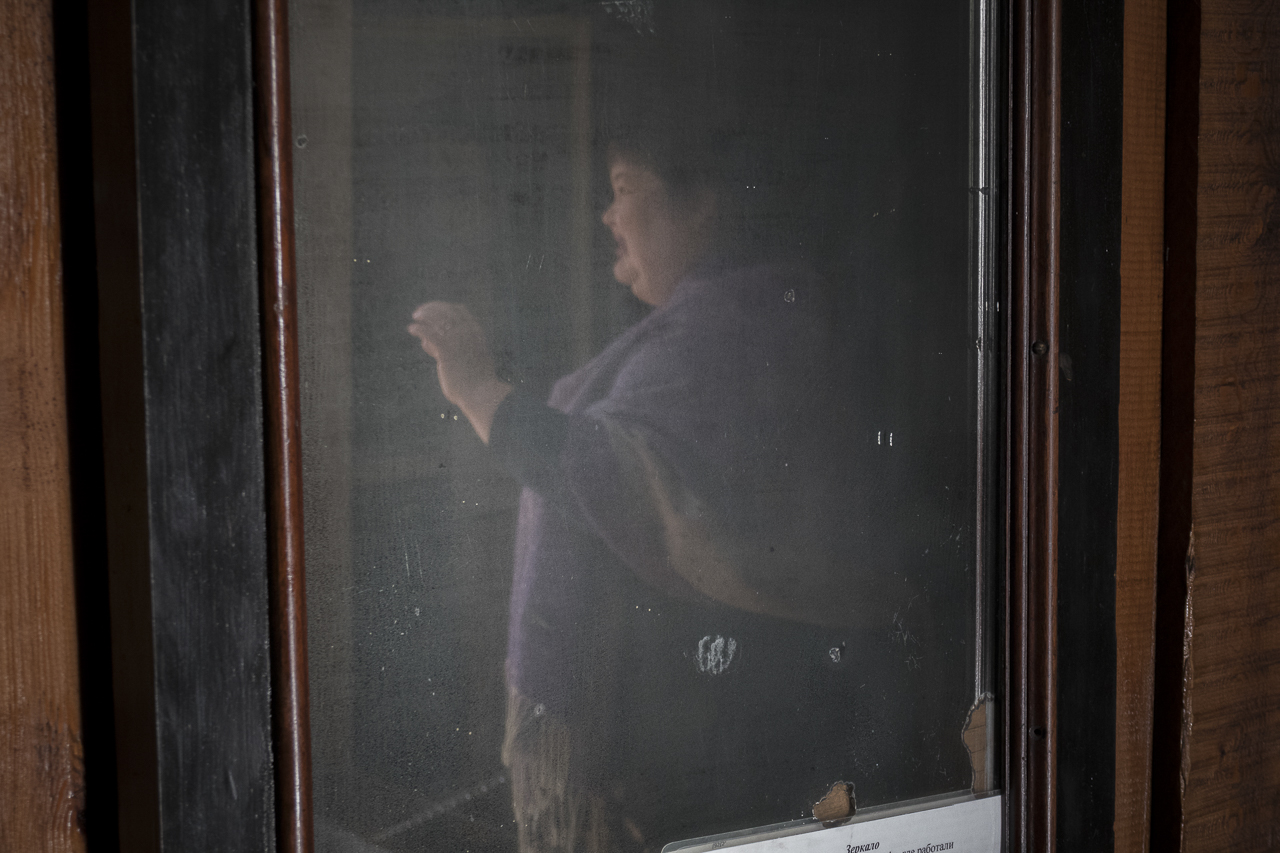

She is AN OLD WOMAN,

VERTOV’S STREET SWEEPER

RODCHENKO’S MOTHER

Looking through SPECTACLES

for other seers like herself

who look

like an audience filled with APPLAUSE

on the cover a book—

filled with photographs of

OLYMPIC CHAMPIONS

doing backflips

to the tune of the INTERNATIONALE

PRINTED

in red and gold LETTERS

now burning inside the CENSOR

next to the tabernacle

in the church of all

that is ICONIC —

TO WHERE THE ETERNAL FLAME HAS SIMPLY SWITCHED SIDES.

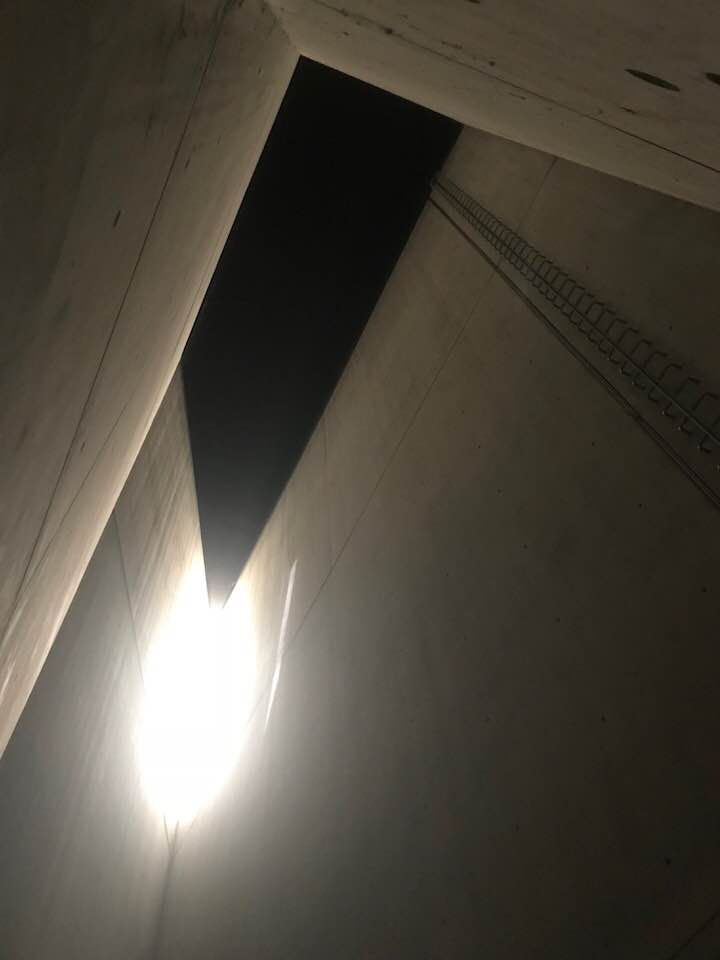

So she kneels

through a PASSAGEWAY

framed in birch

as if GOD were busy elsewhere—

in a black OVERCOAT

smoking and SMILING LIKE A CAT

extending a hand

sealing secrets in wax—

to more easily move the SURPLUS around—

into the STEELWORKS!

into the MEAT PROCESSOR!

WHERE THE FUTURE IS

ALWAYS ARRIVING

ALL WAYS GO FORWARD!