Atlantika Collective Member Sue Wrbican's show titled The Iridescent Yonder recently opened at the Riverviews Artspace in Lynchburg, VA and was reviewed in this space on July 14. During Atlantika's monthly meeting, Sue walked us through the multi-faceted show, which includes photography, painting, and installation. She emphasized that the exhibit was conceived as a response to the tragic loss of both her brother, Matt Wrbican, and her mother within several weeks of each other. In fact, the exhibit centers around a large-scale collaborative painting of an oil tanker created by her brother Matt and two collaborators, Phil Rostek and James Nelson, in 1991. During the walkthrough, we were introduced to Phil, who not only helped us to appreciate the importance of Matt Wrbican's accomplishments, but also regaled us with tales about collaborative efforts the group initiated in the 1980s under the name "DAX," or Digital Art Exchange. Phil's recollections of their joint efforts and the early responses of artists in the 1970s to 1990s to important cultural developments, including the advent of the internet, proved extremely fascinating, and we invited him to elaborate on the very significant "paradigm shift" that he witnessed in art during this period. We hope that this series of posts will not only shed light on innovations in American experimental art during this period, but also flesh out the relevance and significance of Sue's recent work.

by Phil Rostek

The Oil Tanker, a 1991 collaborative work by myself, Matt Wrbican, and Jim Nelson, has seen the light of day after 30 years of storage. Thanks to the energy, commitment, and creativity of artist Sue Wrbican (Matt’s sister), the Oil Tanker now looks like this in the Craddock - Terry Gallery at Riverviews Artspace in Lynchburg, VA. It enjoys a space within Sue’s exhibit entitled “The Iridescent Yonder."

Detail of The Oil Tanker, Matt Wrbican, Phil Rostek, and James Nelson. Discarded plastic objects, paint and tar, 192” x 72”, 1991.

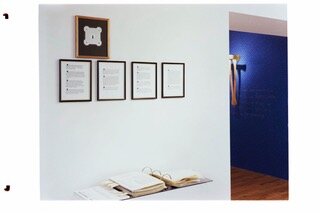

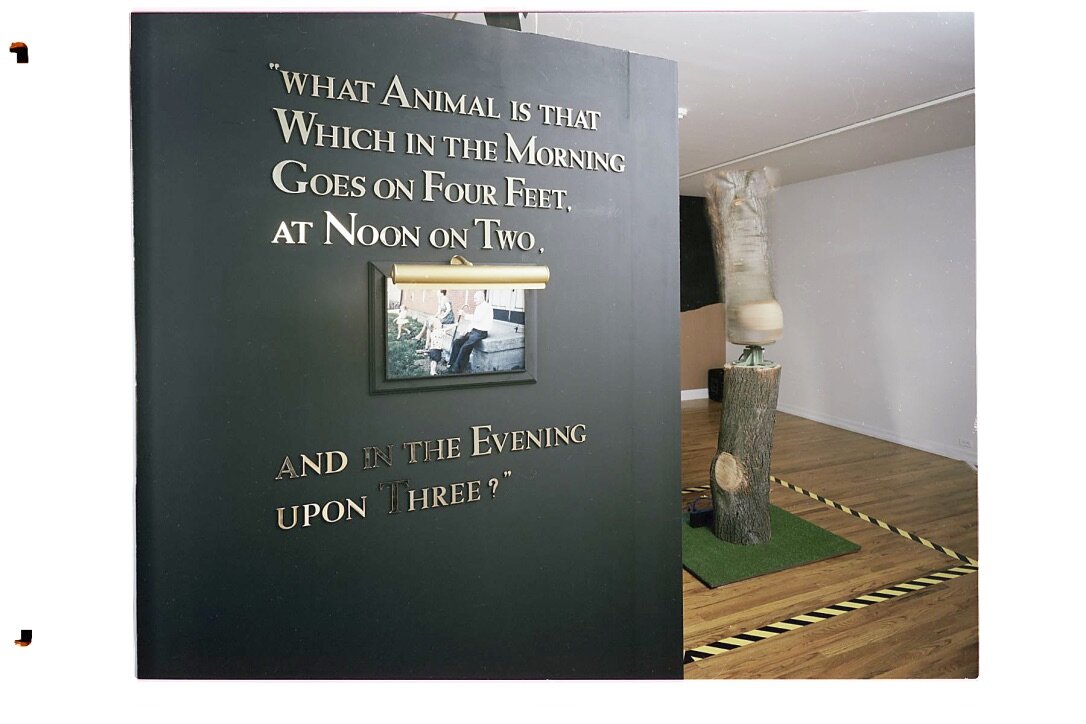

The Oil Tanker was originally part of a larger presentation exhibited at the then Pittsburgh Center for the Arts, National Gallery. It was funded by the Painted Bride / Philadelphia and also was supported by the formidable commitment of director of exhibitions Mr. Murray Horne. The show was called the Labyrinth and it was a “walk through exhibit” - a kind of inventory of effects that intended to stimulate an observer to ponder speculations about what the world was like and where it might be going. In 1991 those conjectures most likely included many of the same thoughts that still plague us today and still require candor and inquiry, i.e., environmental concerns, sustainable resources, reasonable parameters of digital outreach, and the phenomenon of multiple identity.

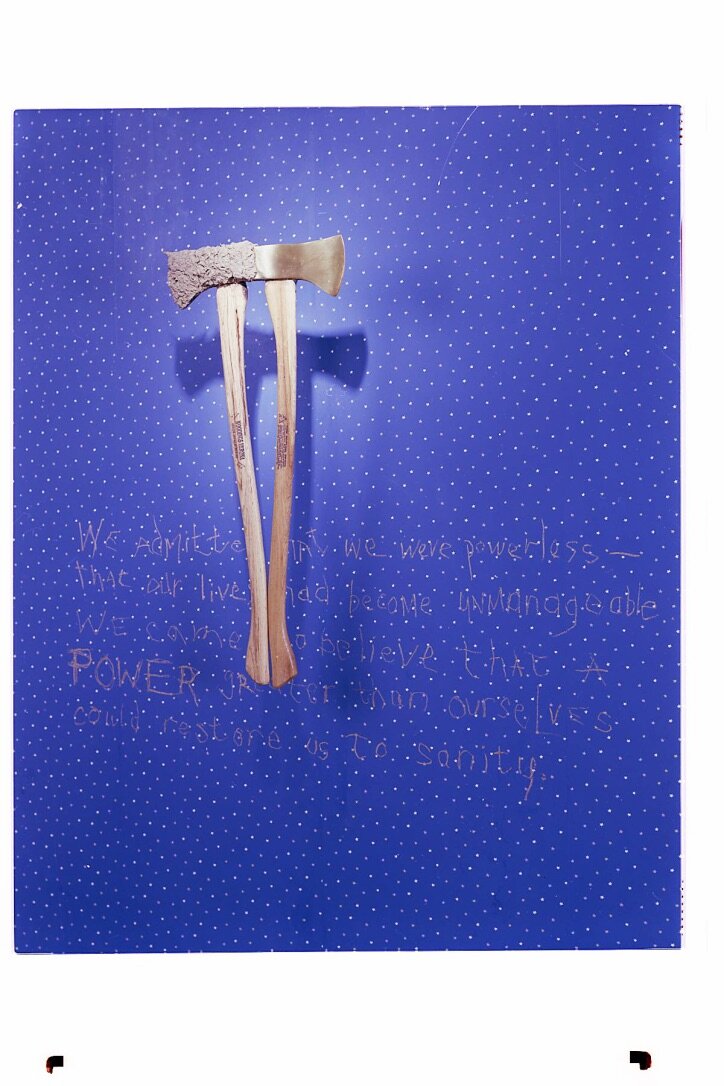

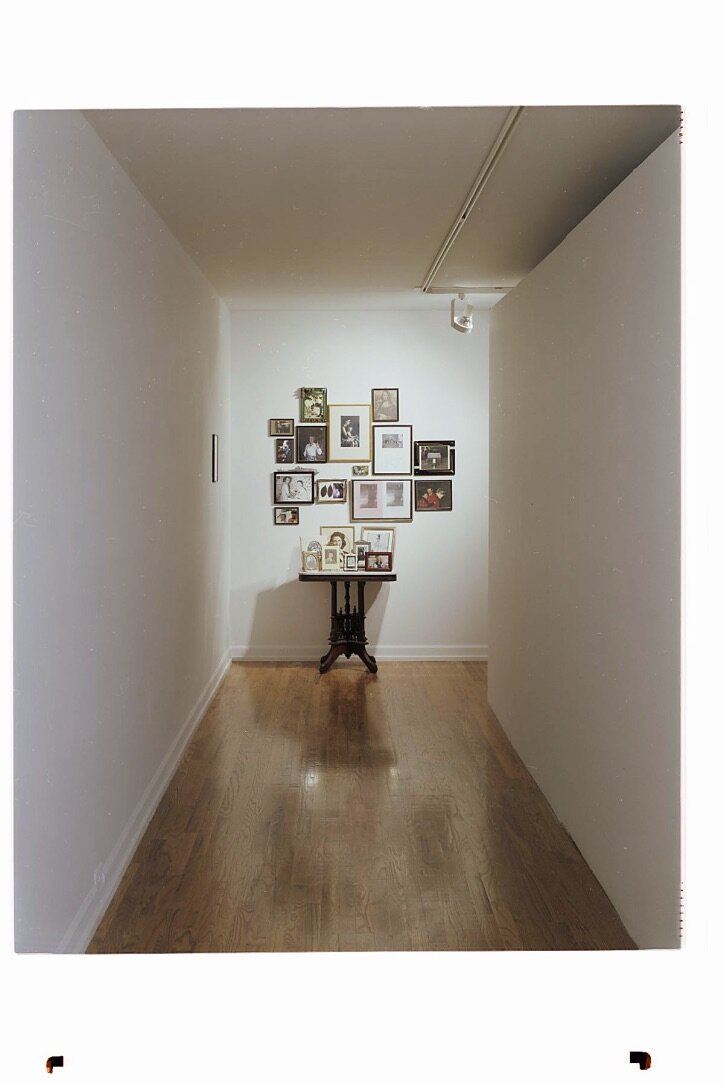

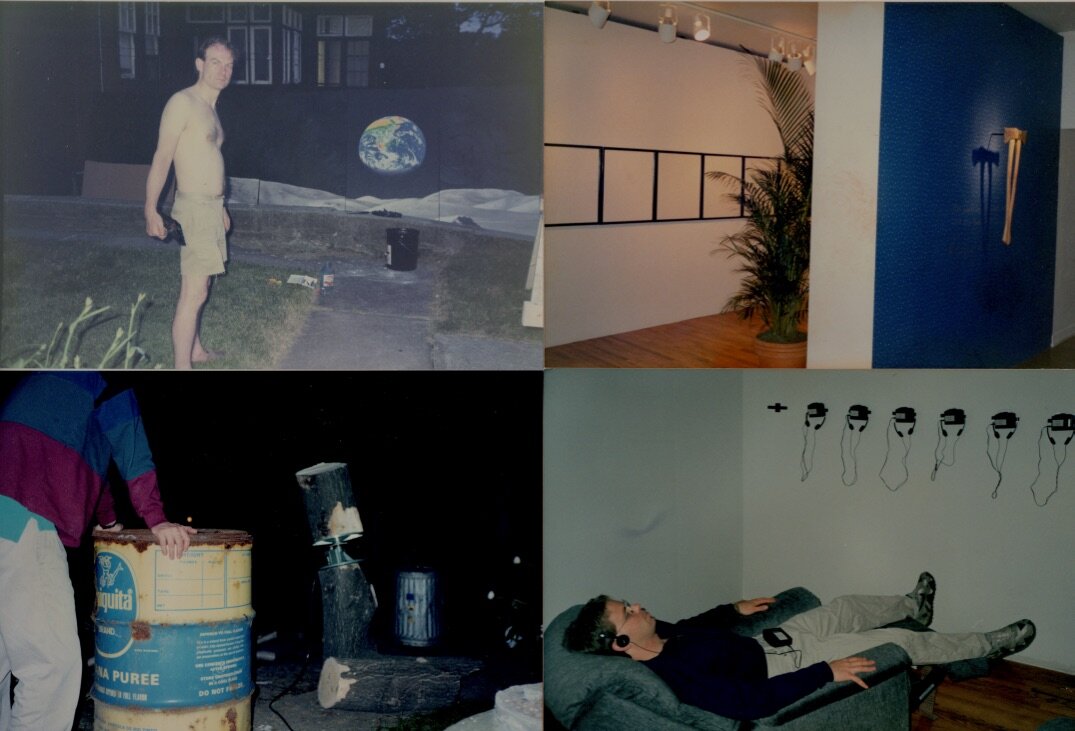

The book of contributors to the Labyrinth exhibit (pictured below) included the conviction that, as organizers of the show, Matt and i considered ourselves “stewards,” not authors. The exhibit included a spinning tree and microphone which looped anything that was said into it. It included wise sentences from historical personalities that were scribed by hand as small as possible. Other rooms included audio tapes and lazy boy chairs, references to Shakespeare, the Ancient Greeks, Alcoholics Anonymous, and a video of Lower East Side metal banging in the Rivington Street “sculpture garden.”

Installation views, The Labyrinth, 1991.

The backstory of Oil Tanker is rather integral to a collaborative effort that included 14 artists all in all. The thrust of the exhibit attempted to laud the virtues of what i called “structural collaboration.” Quite simply that referred to my bias that overt process orientation prioritizes the participants - observers are for the most part left alone to untangle impenetrable interaction. The Oil Tanker may provide a good example to make this more clear.

I thought our Labyrinth should have a “Minotaur” and that was, in my opinion, oil and the amount of it that suffered catastrophic spills back then. Matt and i agreed on this and we invited Jim Nelson to help us express something, somehow. By consensus we agreed a tanker in high profile would fit the bill and agreed upon a rough thumb nail sketch. Later there was a separation of input. I did the tarry water, Matt worked inside the outline of the boat, and Jim painted a background setting.

Here’s me with the initial idea.

Phil Rostek standing with the original concept drawing for The Oil Tanker, 1991.

Here’s Jim Nelson painting in the background, which evoked The Gulf War. I met Jim at Carnegie Mellon University in 1971. Our graduate student studios were in the basement of the Margaret Morrison Building on campus. We remain very close friends to this day. I’m pictured also - touching up the tar at the bottom of the painting.

Jim Nelson and Phil Rostek creating The Oil Tanker in 1991.

And here is the creativity of Matt Wrbican who saved oil based products for months and then organized them from thin to high dimension within the hull of the Tanker. Neither i nor Jim was expecting the passion that Matt brought to the project; but i was not surprised then nor am i now. Matt Wrbican was a unique and stellar talent.

Plastic (petroleum-based) objects collected by Matt Wrbican for use in the creation of The Oil Tanker, 1991.

There is something ineffable about my experience in Lynchburg. It haunts me in ways that evoke, or perhaps better, reawaken the aspirations of The Labyrinth. Seeing the Oil Tanker but not seeing Matt was telling. The Labyrinth exhibition coincided with the retirement of my mentor and Matt’s mentor - Bruce Breland. I studied with Bruce as a grad student at CMU 1971 to 73. We did mail art and concept pieces together. i had given up lyrical painting and opted to wear white tie and tails to school every day. I was also studying with Robert Lepper - a teacher of Andy Warhol. Between Lepper and Breland is a volatile and heady place to be. Each had a keen sense of the absurd, and at the same time, each had a keen penchant for very pragmatic thinking. Both liked Duchamp. My leanings toward Fluxus would later inform my thinking when i wrote theory for Bruce Breland’s DAX Group (Digital Art Exchange) in the 80’s.

Phil Rostek, from a photograph by Bruce Breland, 1973.

It was in the 80’s that i met Matt Wrbican. Matt was then a grad student working with Bruce in coursework called “intermedia.” During the decade of the 80’s the DAX Group contributed to many distributed authorship pieces during the early days of the internet. La Plissure du Texte 1983, a text exchange organized by Roy Ascott comes to mind - as do contributions to Network Planetario / Laboratorio Ubique at the Venice Biennale 1986.

By the end of the decade Matt was working at the Carnegie Museum of Art during the installation of a Carnegie International, archiving Breland’s legacy at CMU, and doing the Labyrinth show with me -all at the same time. It was stressful for Matt but he succeeded in doing it all. He was, very shortly afterward, hired by the Warhol Museum as an archivist in charge of moving work from Warhol’s factory to Pittsburgh. Matt is identified with the Warhol time capsules as well acknowledged as one of the foremost authorities about the life and art of Andy Warhol in the world. That is not an overstatement.

As i step back now and think about the volatility of those times; i cannot say that i have much to contribute to the understanding of it all. Great turmoil was let loose when “the individual was replaced by the collective’” via technological innovations; innovations that spawned an unprecedented acceleration of information. Information speed-up continues to shape the world and the people who live on it. The relationship between art and life seemed obvious when NYC was a center. The very notion of a center continues to fade into a horizontal world that runs flat. The Labyrinth tried to anticipate what future existence would be, and the Oil Tanker was something that seemed necessary to avoid and replace.

More installation views of The Labyrinth exhibit, 1991.

It seems that having one foot in a national world and one foot in a global one - is a chasm that has not narrowed but widened.

As science takes the place of art and religion, one area seems impervious to any form of apprehension. If i could replace the Oil Tanker in today’s Labyrinth, if i could speculate about Minotaurs today, i would offer this. The one area where there has been no “progress” or even significant conjecture is: an understanding of what consciousness actually is. We know it’s what disappears under anesthesia, but we don’t know much more than that. Science would deny that dead things have it at all. But when it is present as a combination of multi-sensory experience and flux - what we commonly call life - it seems to avoid science’s favorite word: “someday.”

It is curious when the notion of “what” is eclipsed by the notion of “how.” Hyper-individualistic living begins to fear time itself. Humility becomes obsolete. A culture, or the tribal equivalent of it, comes to think that time can be reversed and, moreover, that it can be reversed in the spirit of righteousness. The effect of information overload does not see the imminent dangers of the present; it ironically draws obsessive attention to the past. Somewhere in the meat of the brain there is a capacity to recall times that have gone by - but in today’s culture this can only be noticed in the context of the present.

What do contemporary people do when eternity itself has become a thing of the past? That is what i felt when i saw the Oil Tanker after all these years. That faint glimmer of who i used to be seemed unusually informative. That feeling is connected to the elusive charms of what we call, for lack of a better term, art.