Gabriela Bulisova & Mark Isaac

One day, we woke up and an African-American man was President. One day, we woke up and gay marriage was legal. One day, we woke up and the majority of Americans supported Black Lives Matter. When will we wake up on climate change?

You’ve probably already tuned in to one of the many commentators saying the pandemic can be an inflection point, and we don’t have to go back to the way it was. But on the other hand, isn’t a return to normal what most of us want? Shouldn’t we use the car now because it’s not safe on public transit? When can we drive to the beach or get back in an airplane? When will things get back to the way they were?

When fear of the virus finally lifts, when it’s truly safe to drink in a bar, eat in a restaurant, pray in a church, take in a concert, and go to a football game without a mask and without distancing, we could pretend that things are back to normal. But it would be magical thinking.

In June, it was 88 degrees in a small village on the Arctic Circle called Russkoye Ustye. Most summers, they use snowmobiles to get around. In Siberia, where temperatures are increasing almost twice as fast as other parts of the world, temperatures were almost 20 degrees above average in May. The latest research shows that, even with strong climate action, there will likely be a total loss of summer sea ice in the Arctic before 2050.

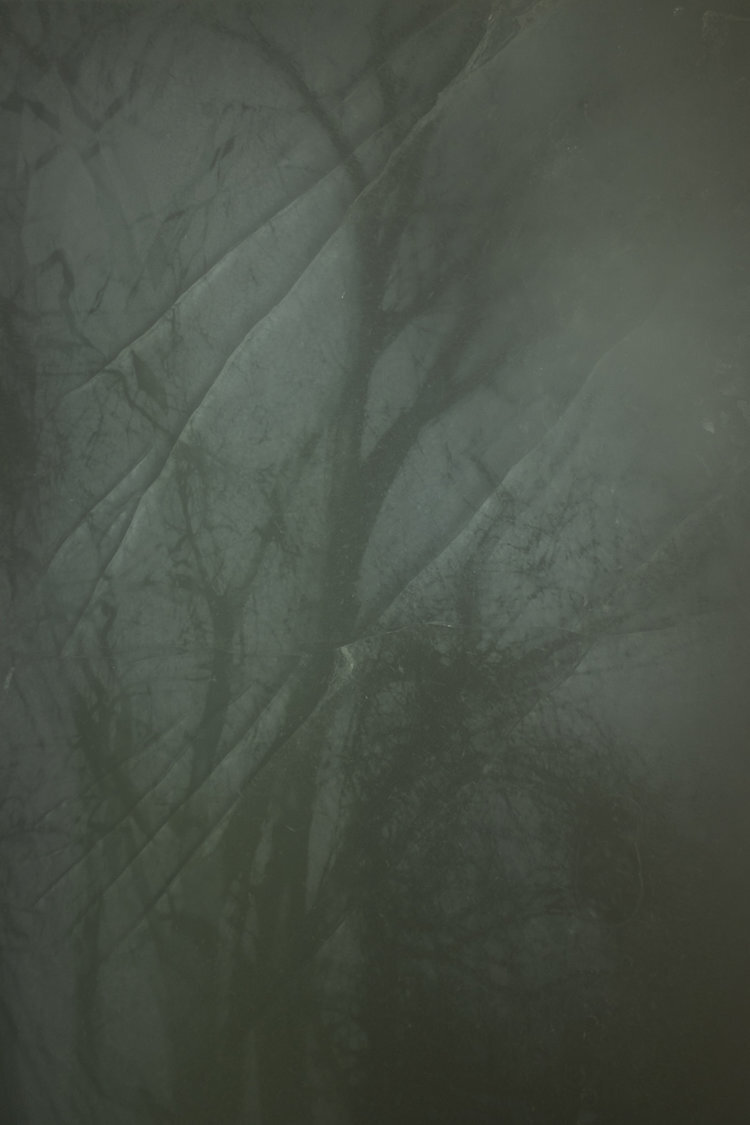

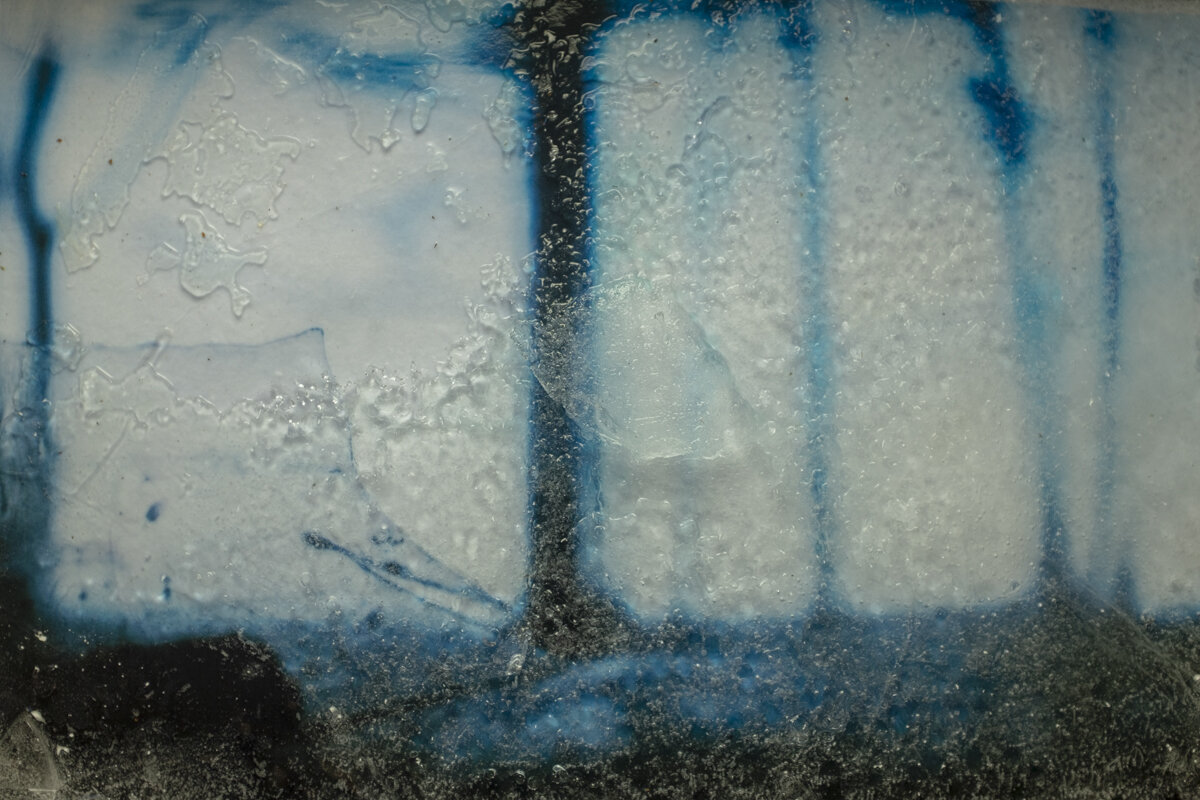

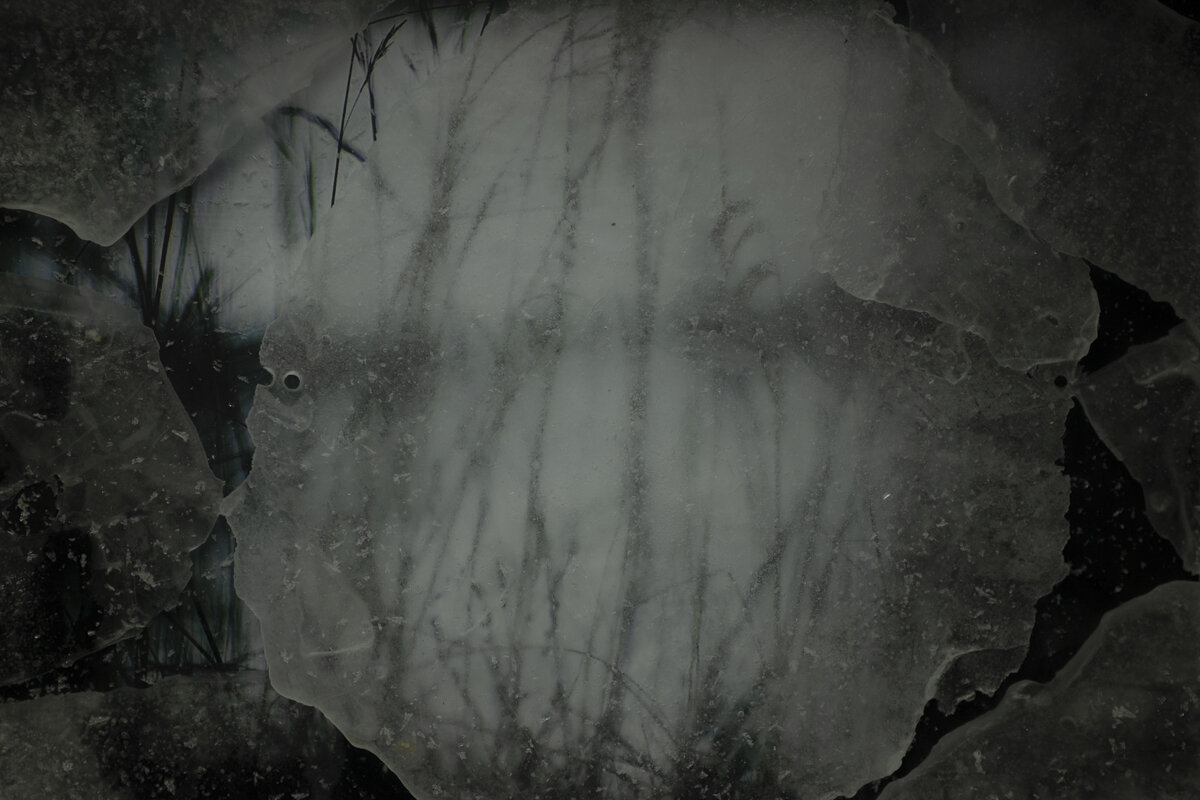

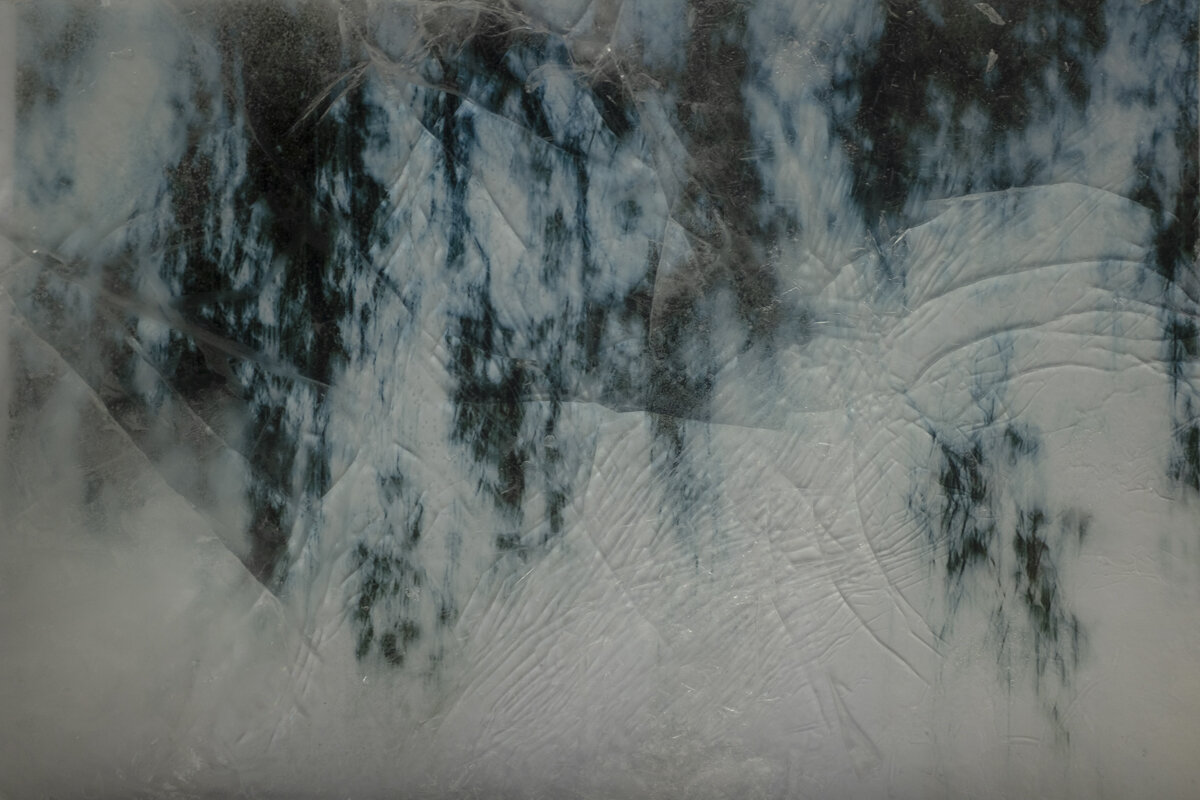

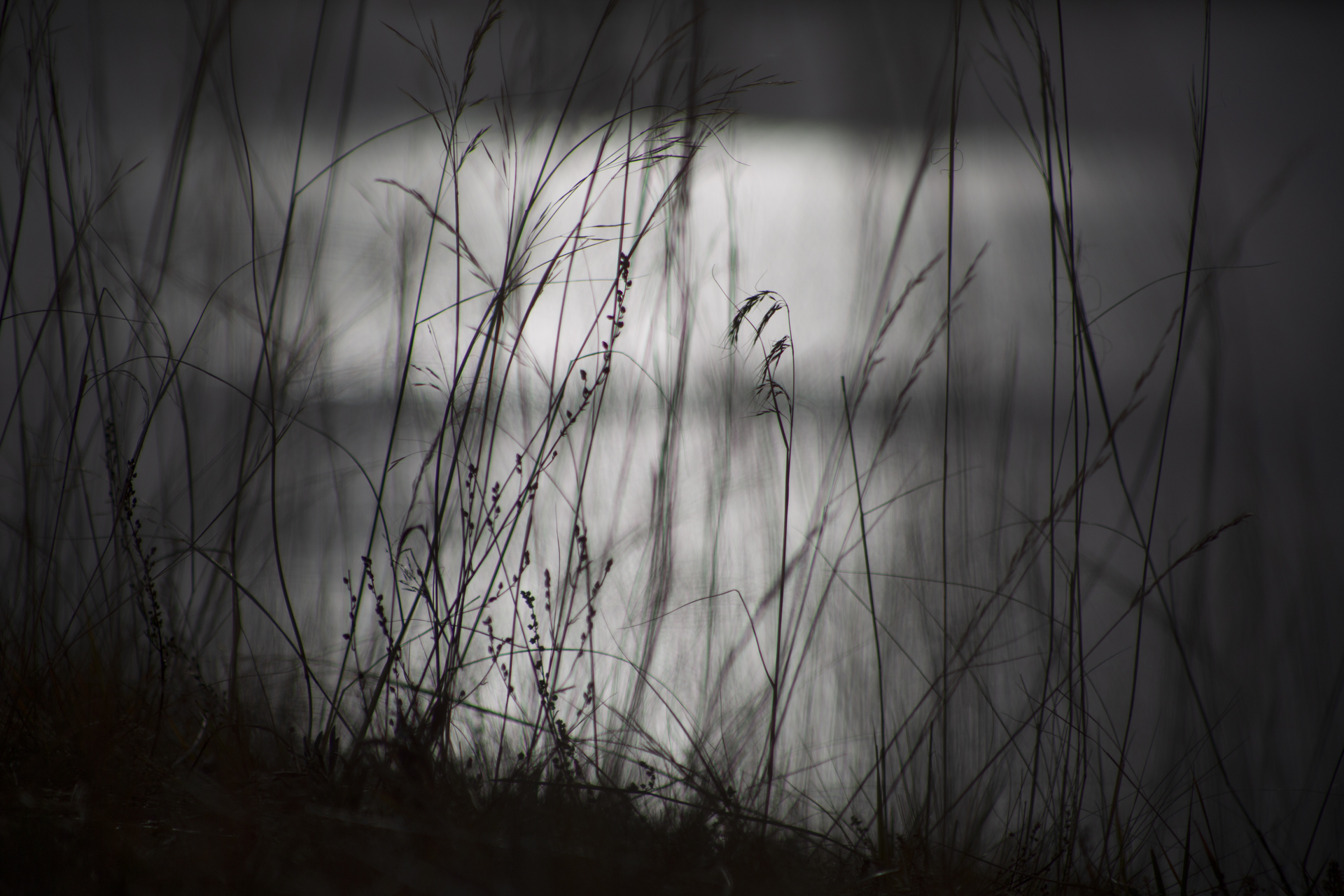

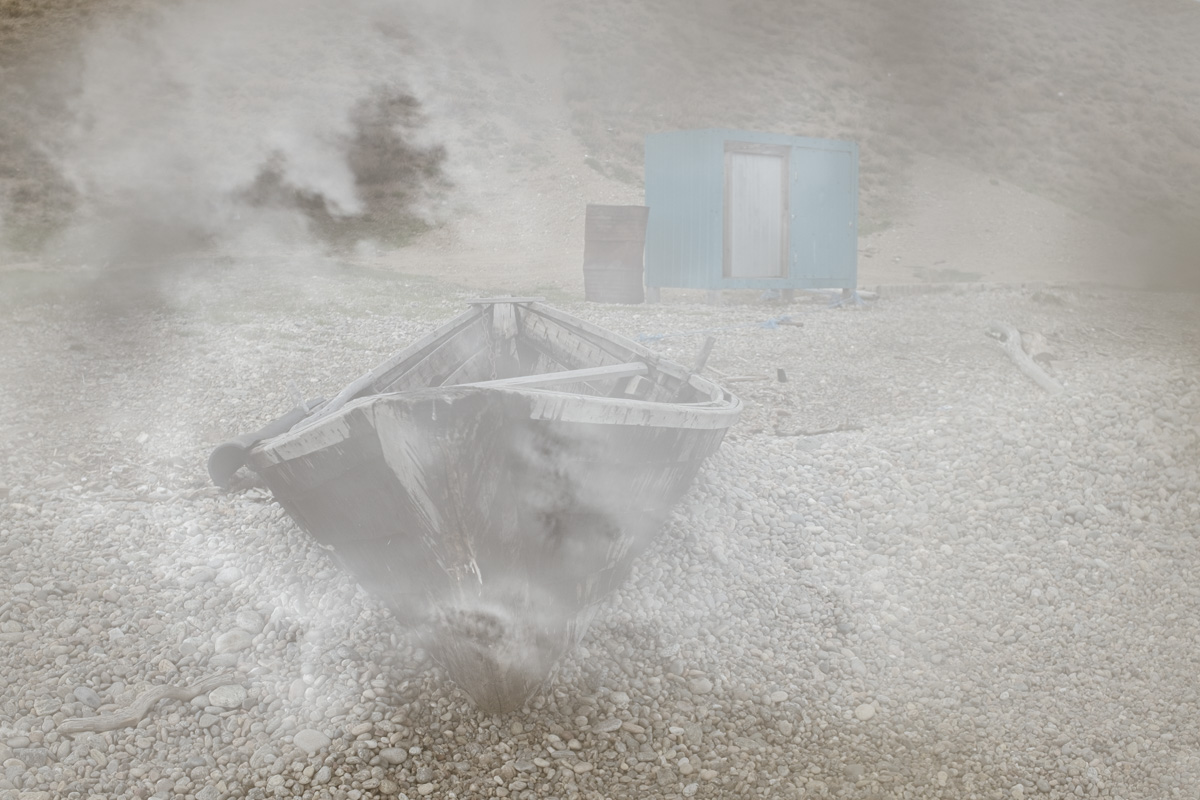

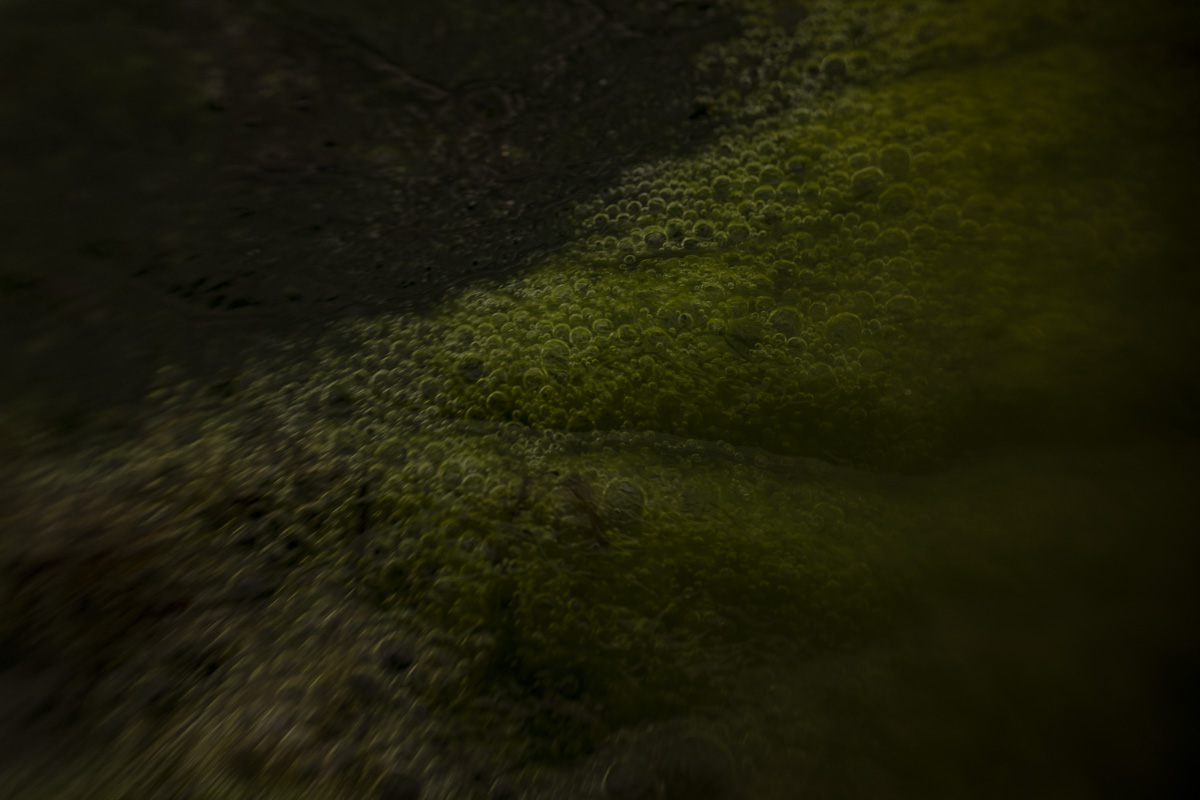

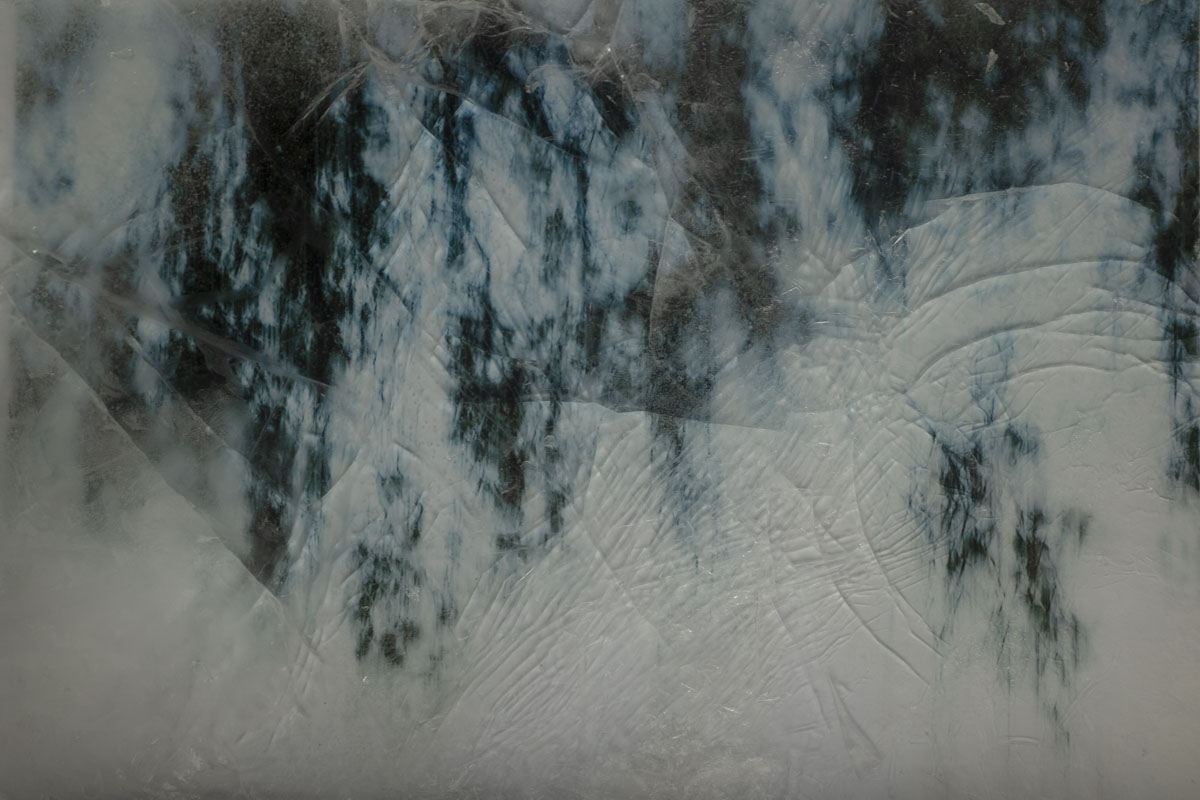

The Irkutsk skyline in Eastern Siberia is darkened by smoke from distant wildfires in July 2019. Also shown is the damage done to nearby forests by wildfires. In the summer of 2019, forest fires the size of the nation of Belgium destroyed precious woodlands across Siberia. Similar fires this year started much earlier and threaten to compound the damage.

Last July, as we finished our Fulbright grant focused on Lake Baikal in Siberia, wildfires the size of the country of Belgium were consuming Russian forests. The smoke wafted across thousands of kilometers and entered Irkutsk, the city we were living in, turning the skies into a murky haze. This year, after we won a second Fulbright to Russia (already delayed due to the pandemic), the fires got off to a much earlier start, consuming vast swaths of these precious forests as early as April.

And the melting of permafrost is accelerating. In Siberia, Canada, Alaska, and other northern territories, roads are buckling, buildings are cracking, and most threatening of all, vast quantities of methane risk being released, with the potential to accelerate warming in a “feedback effect.”

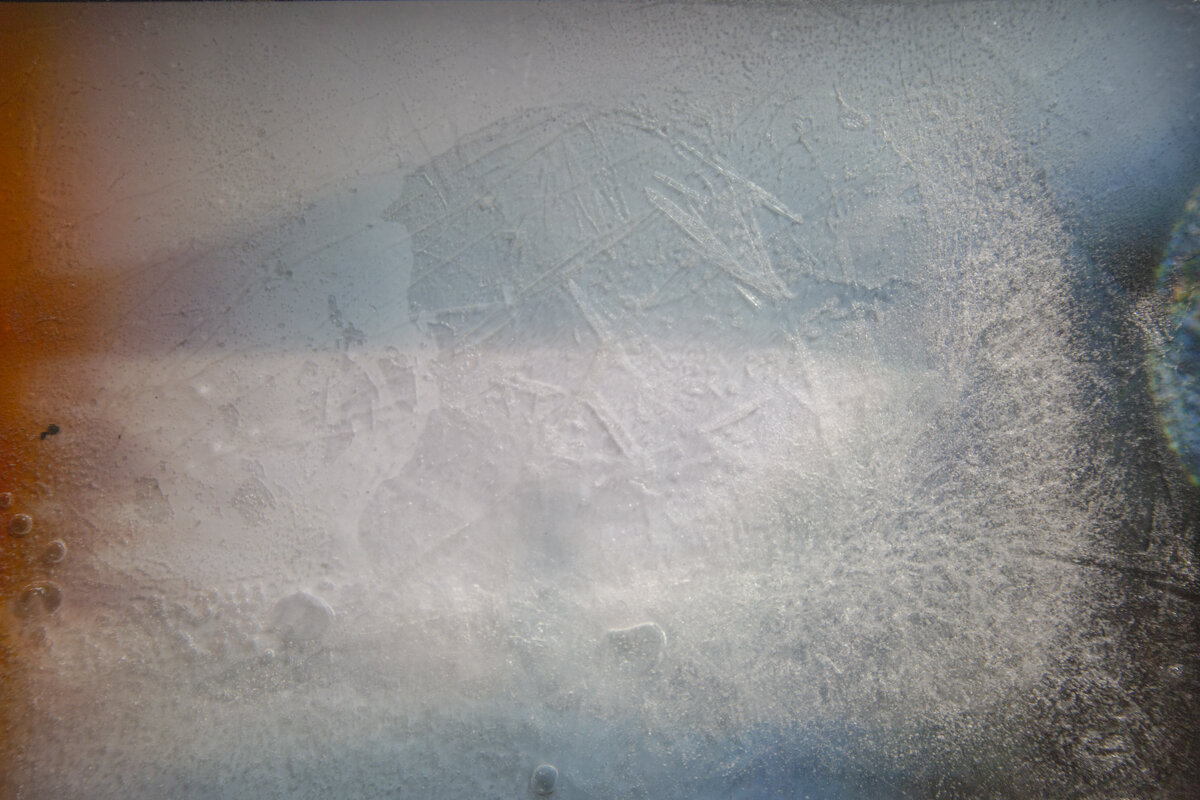

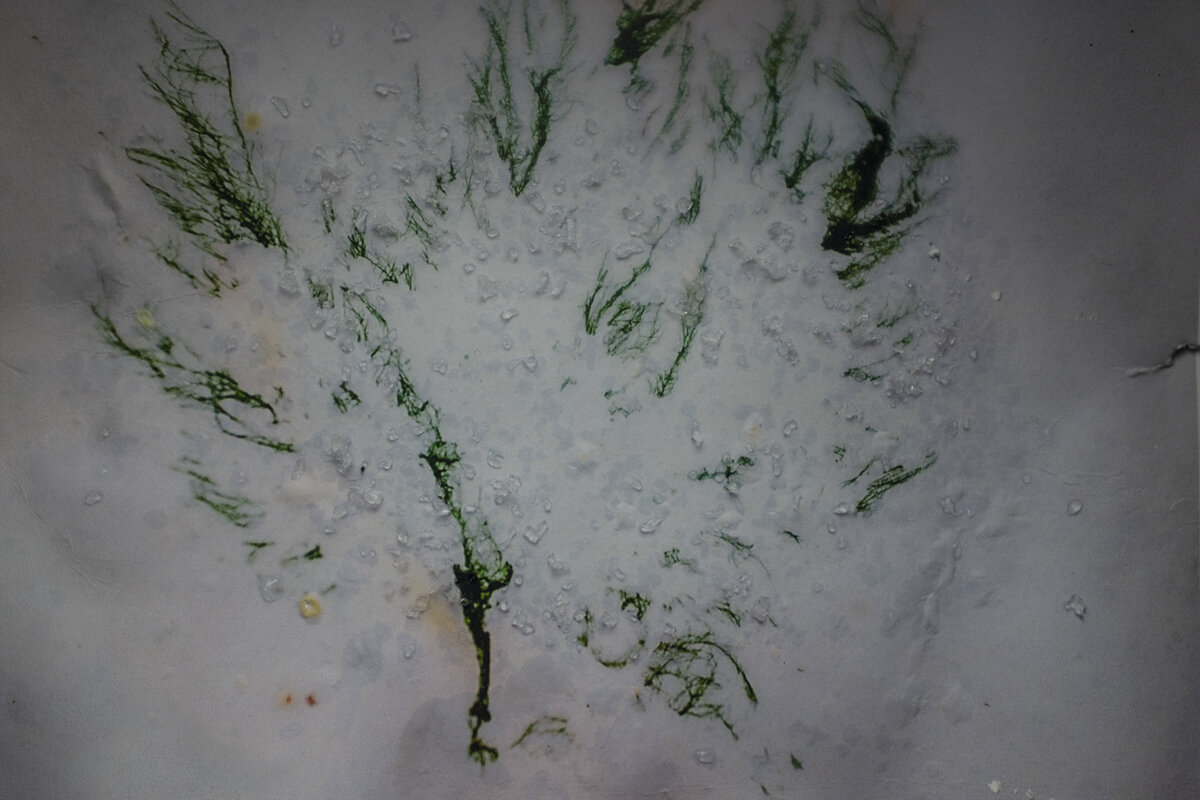

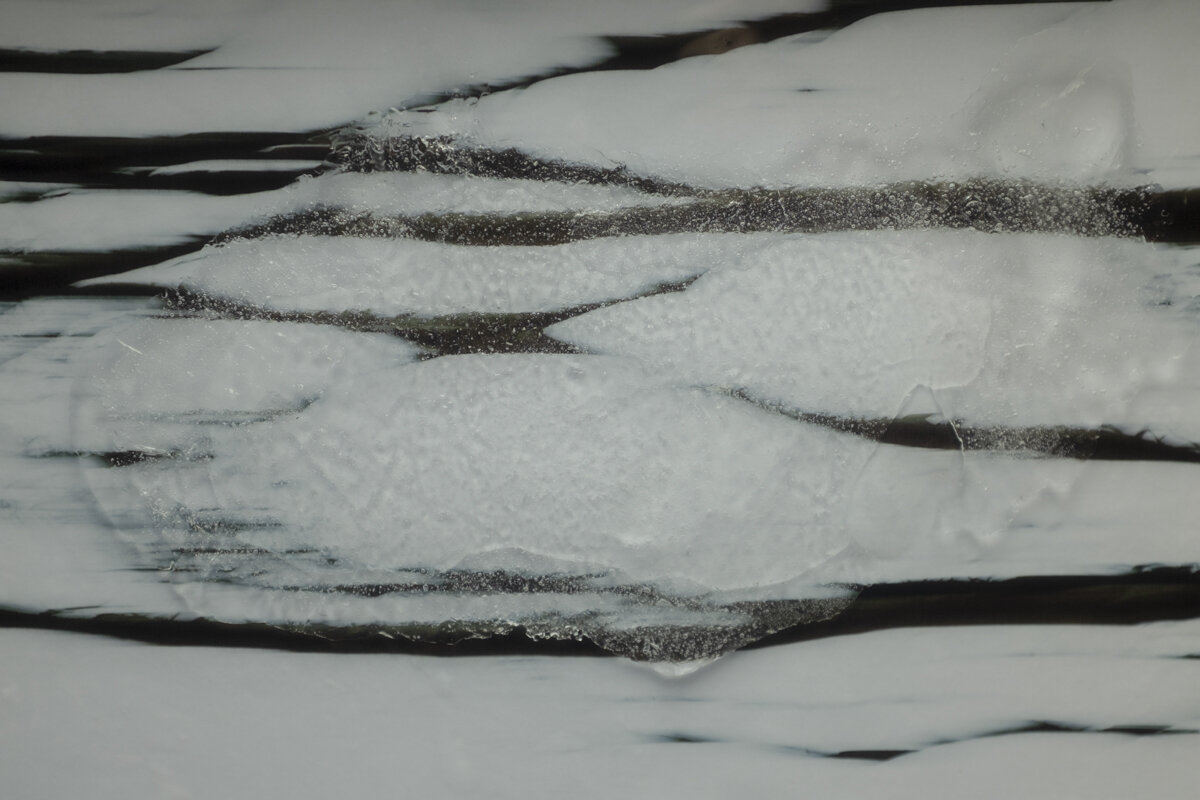

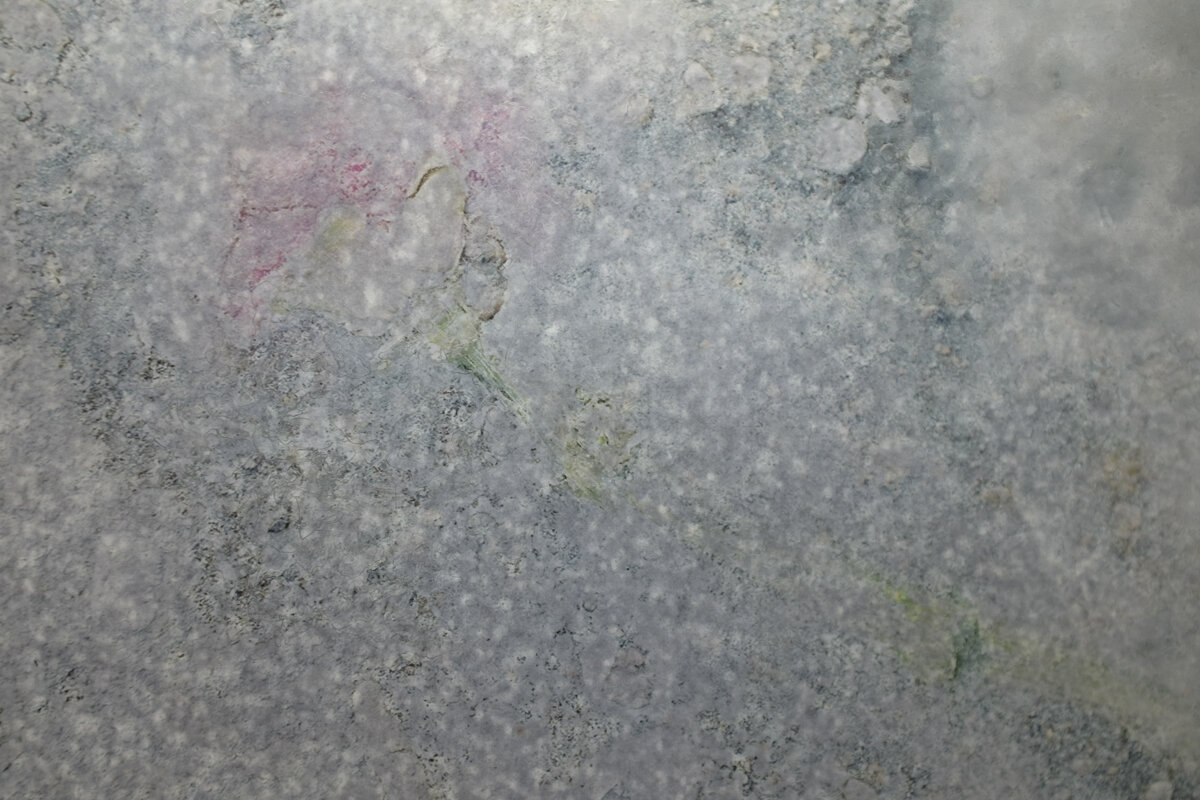

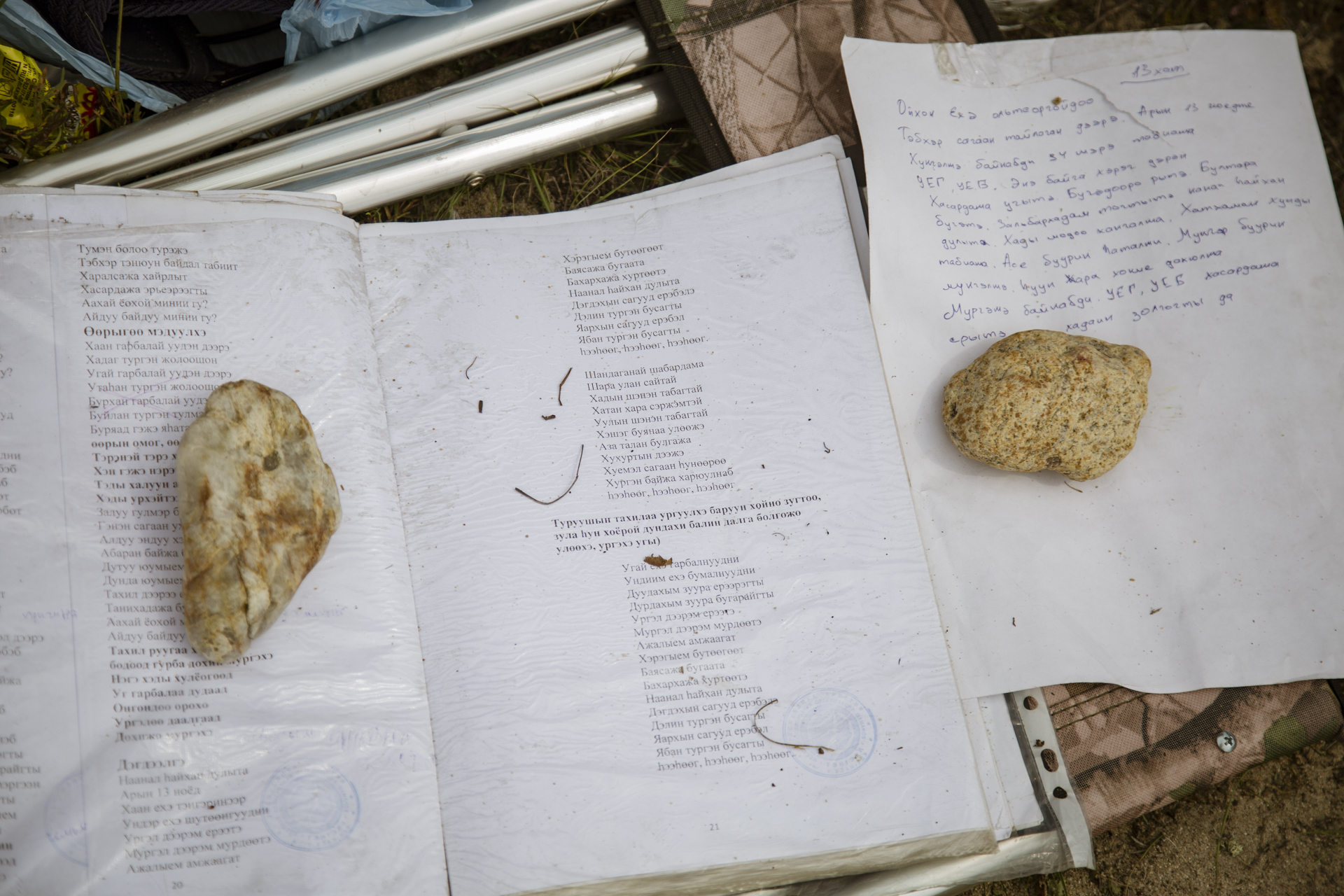

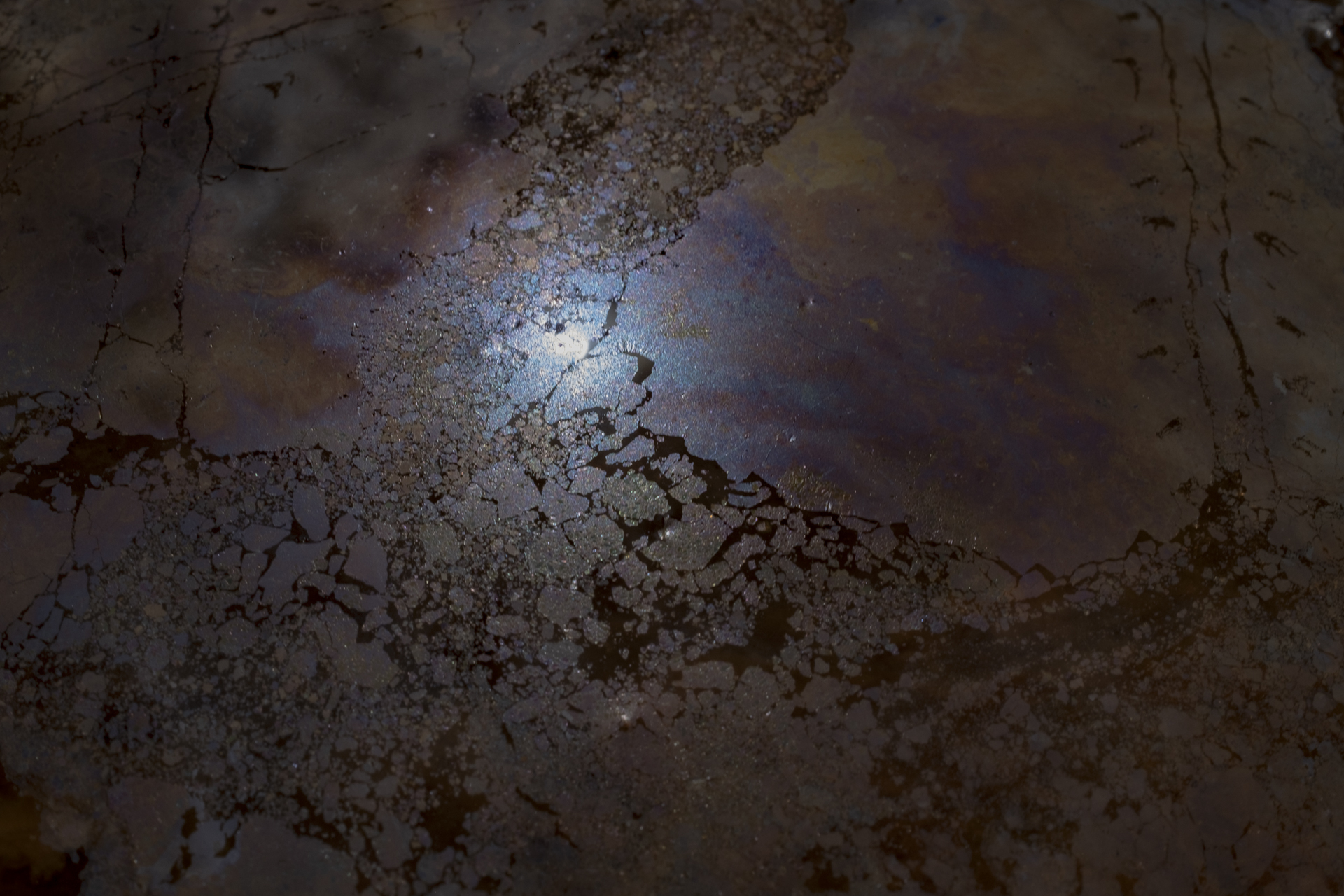

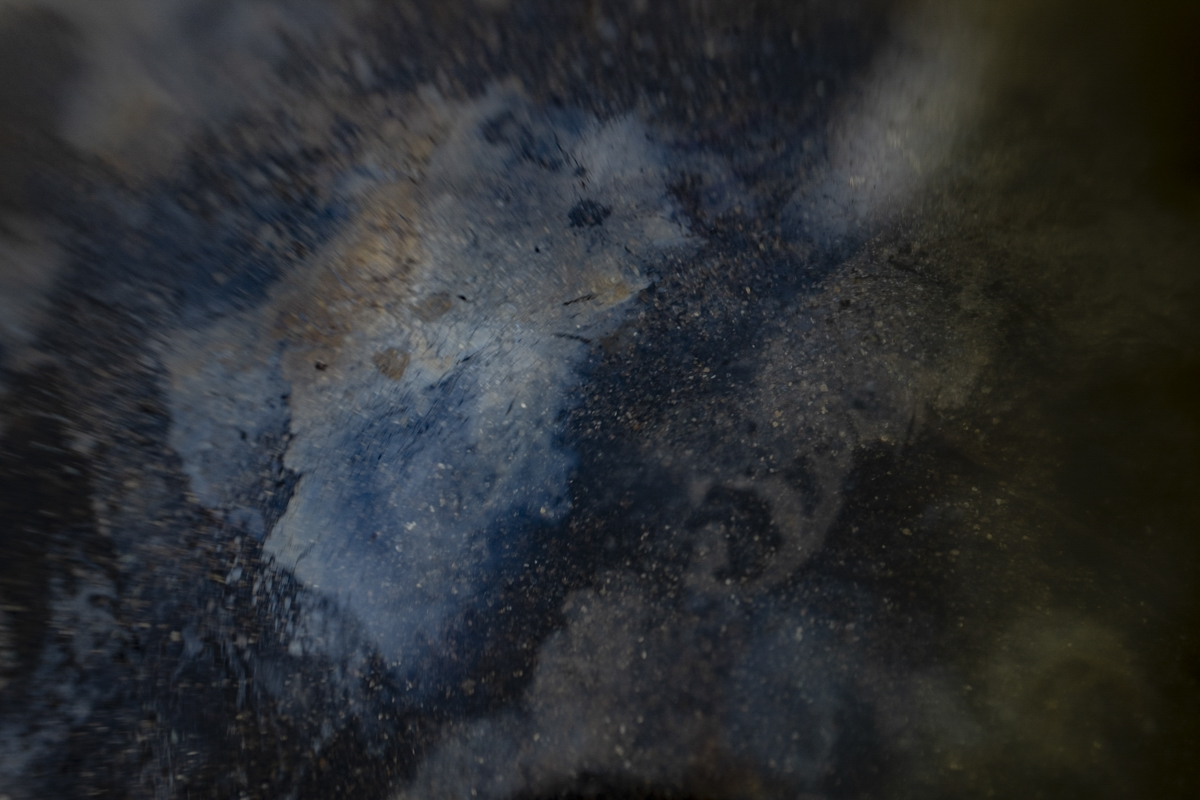

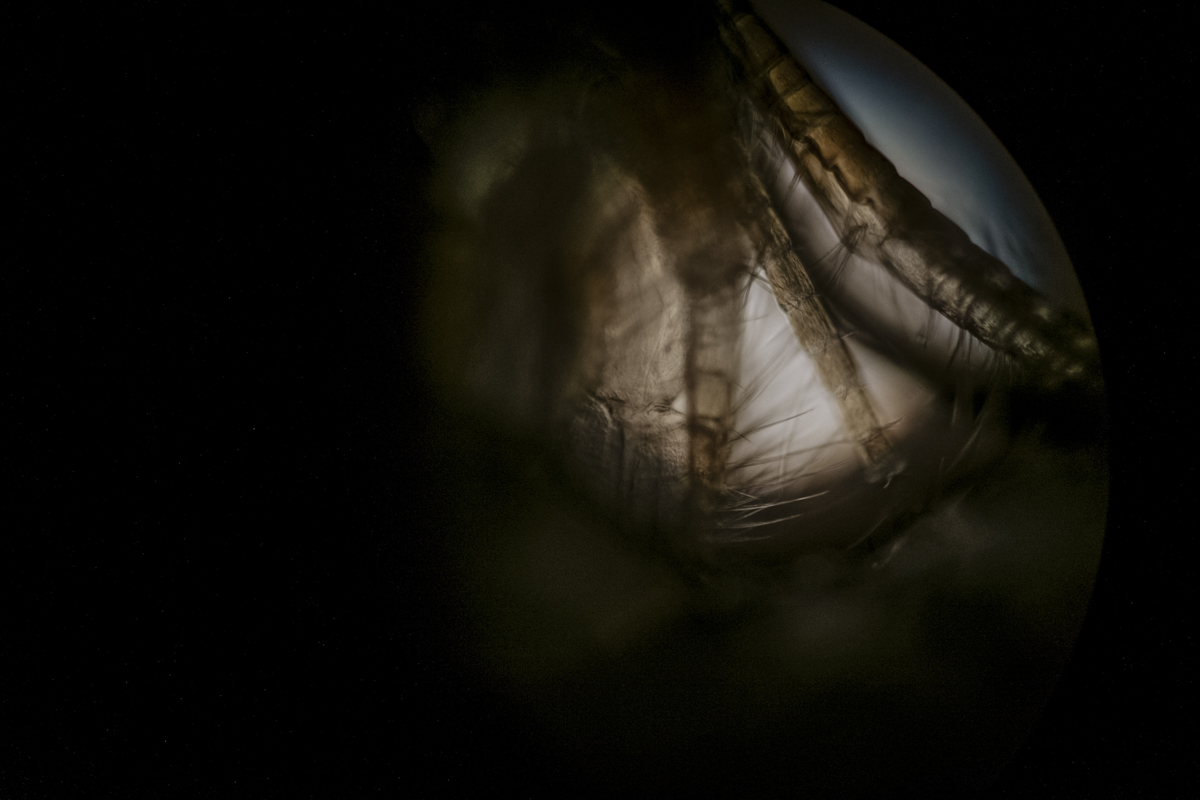

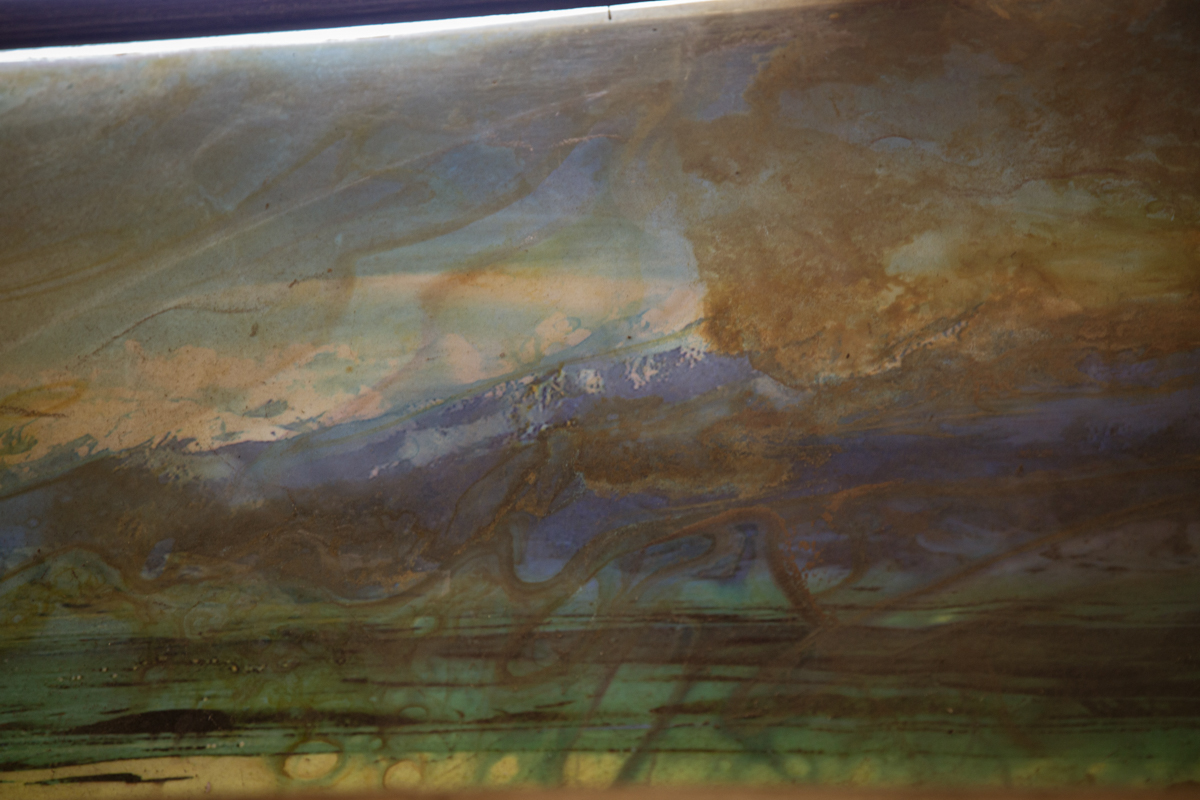

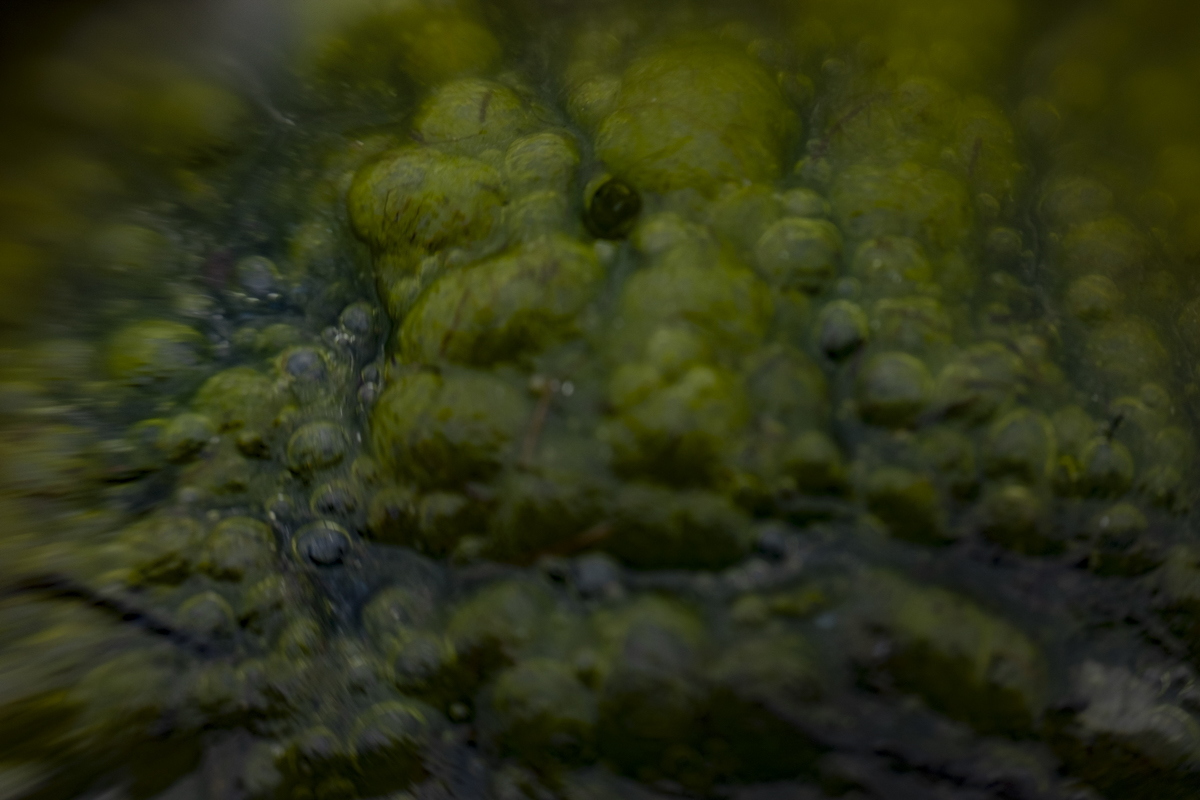

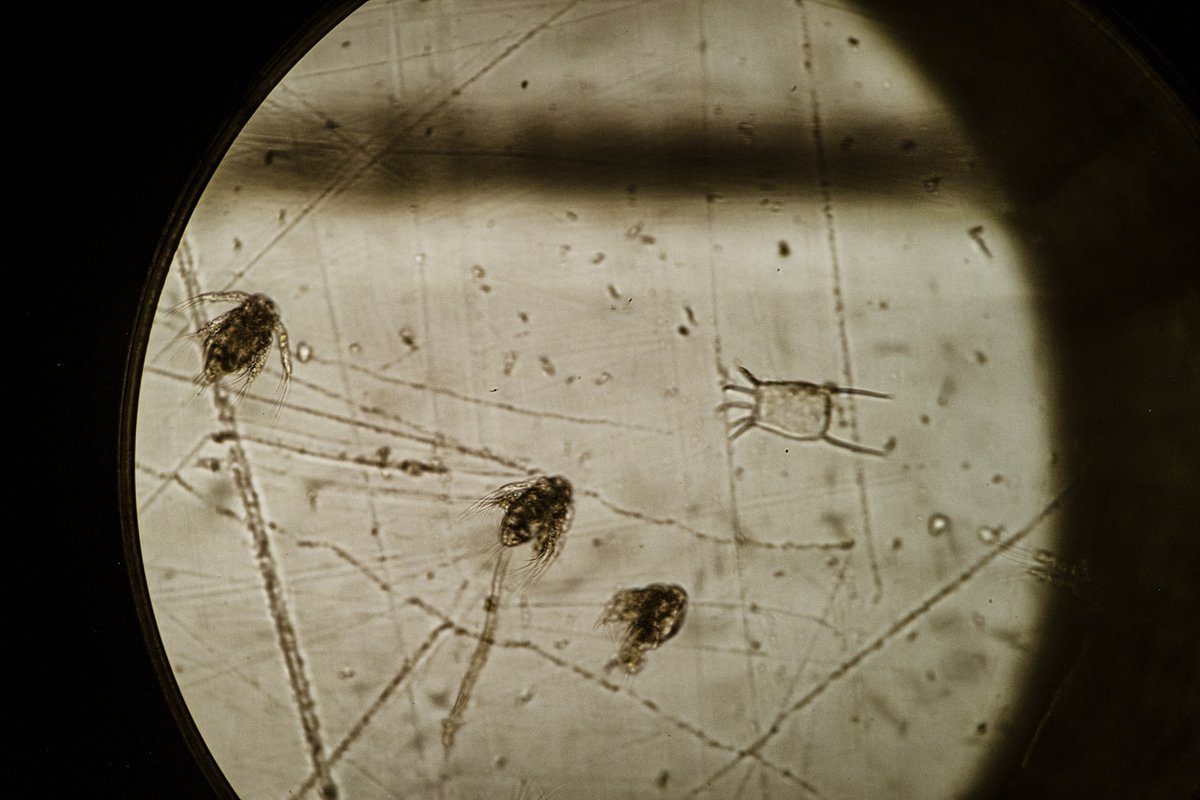

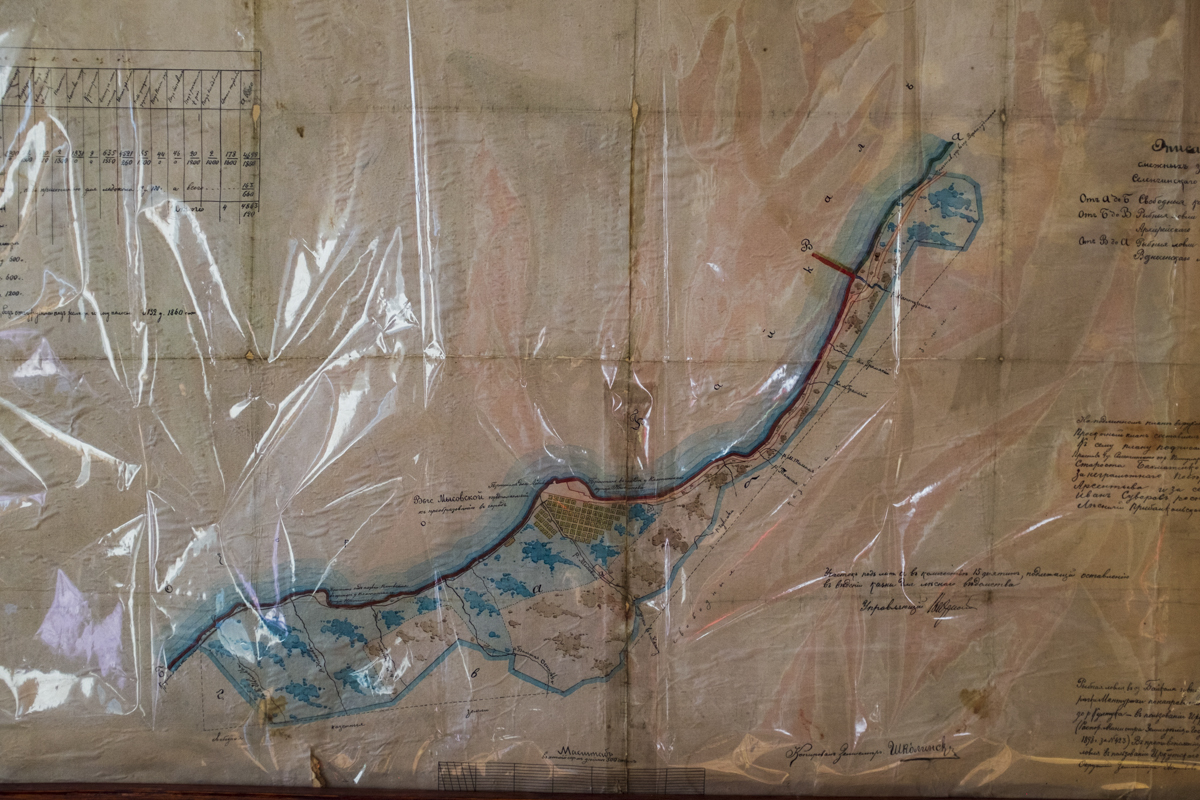

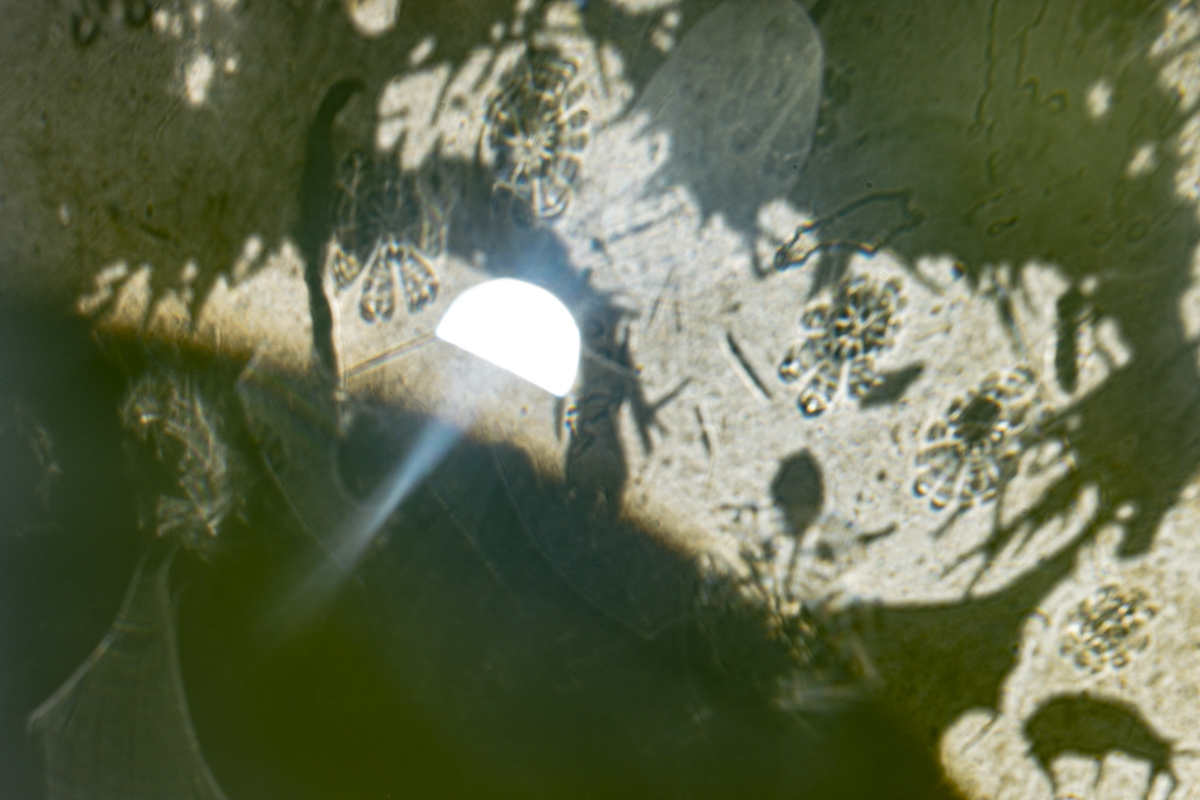

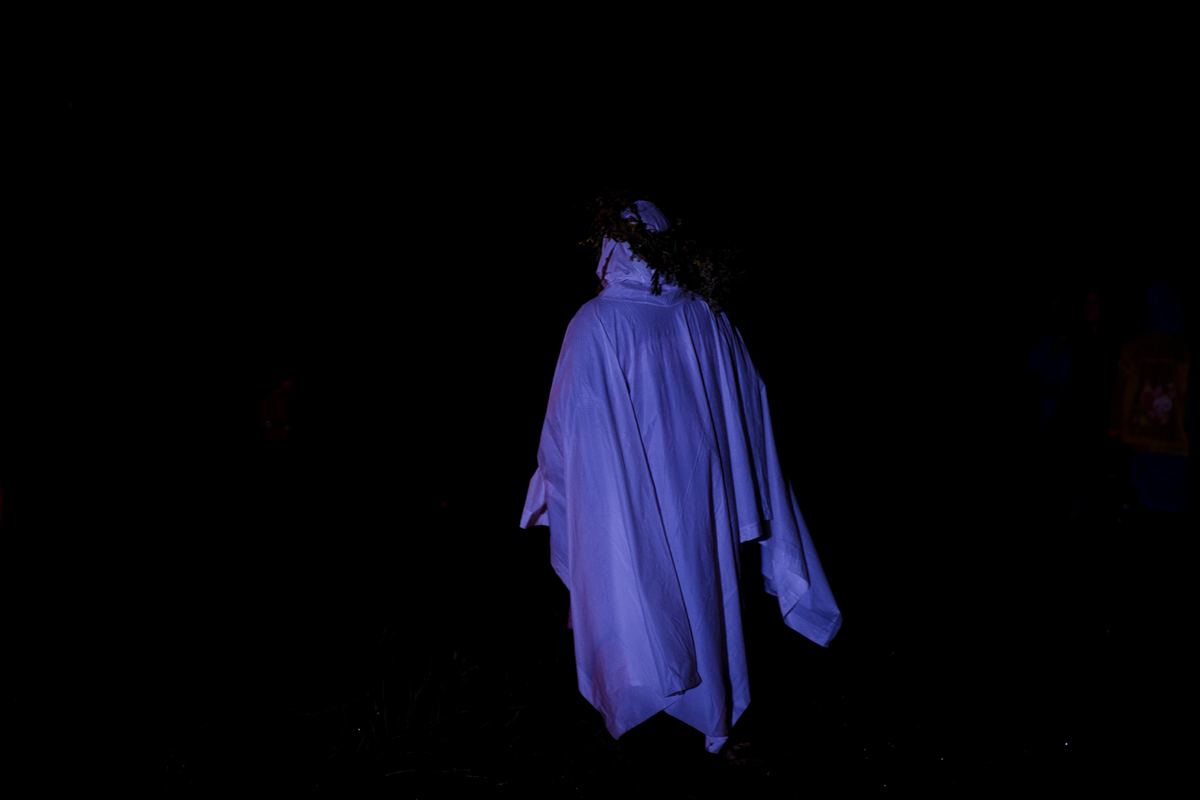

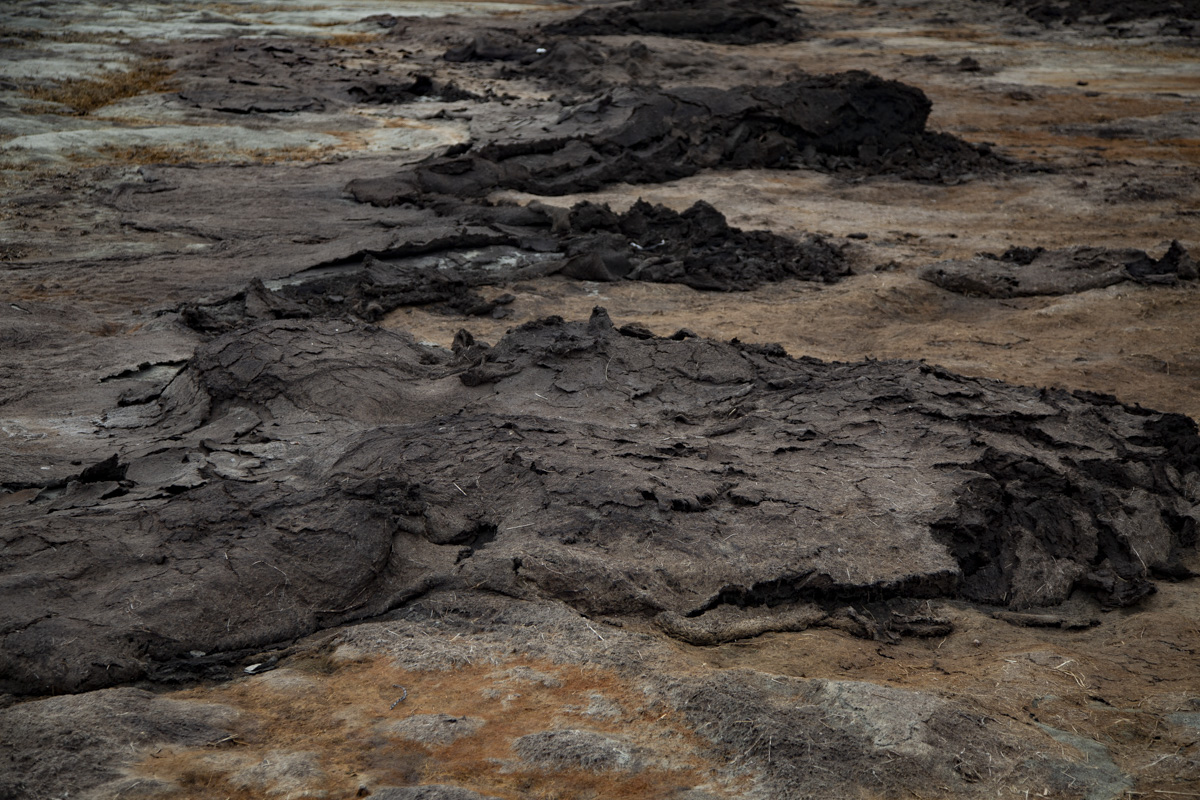

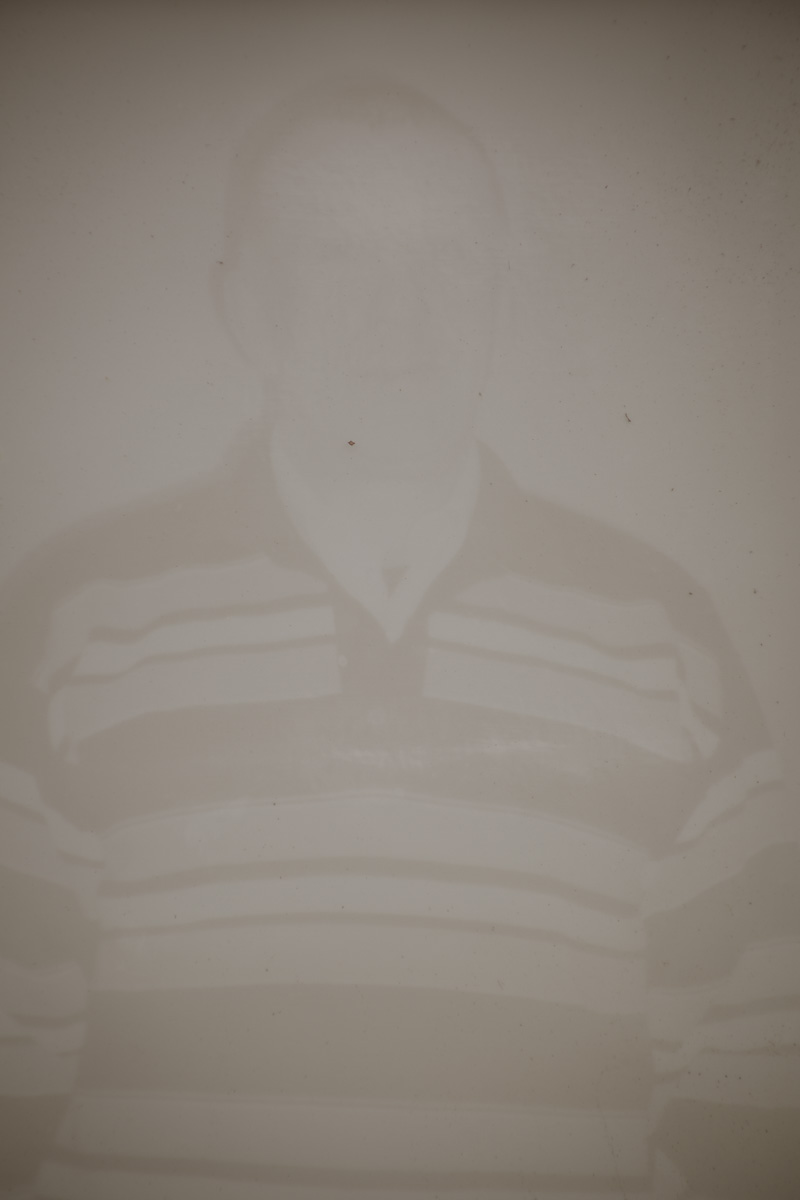

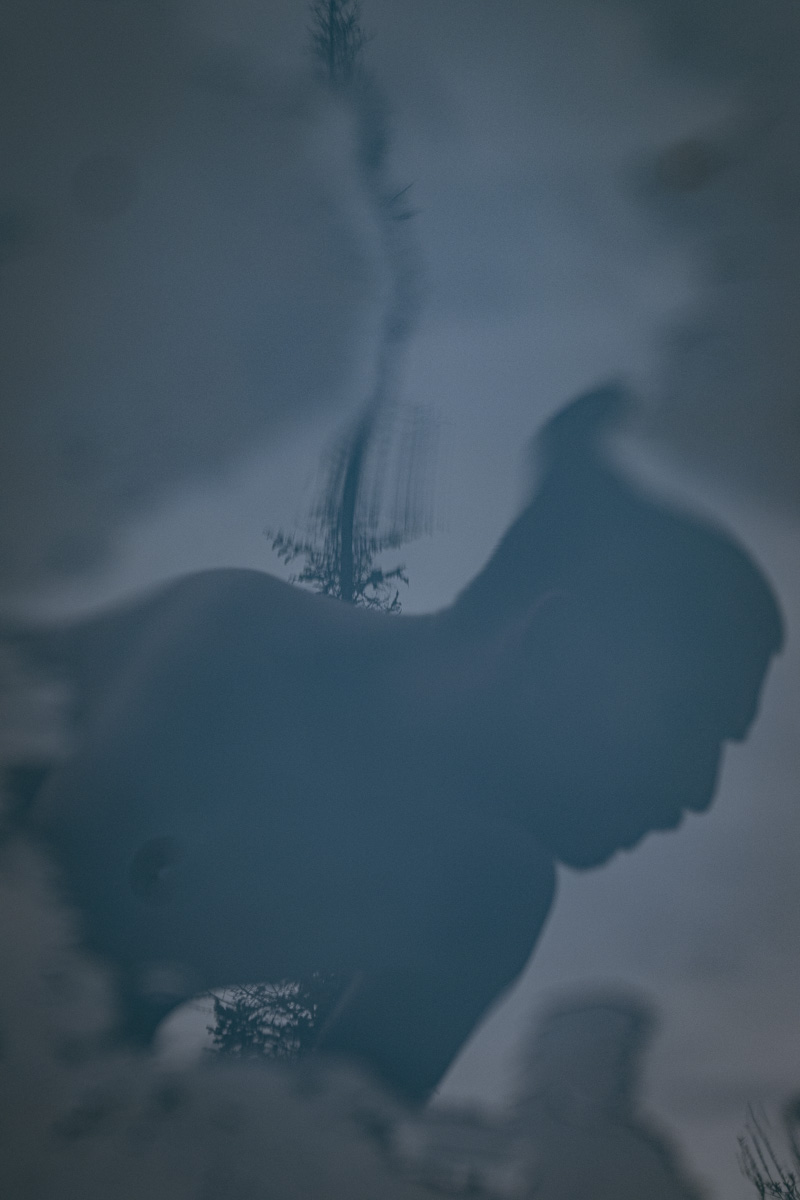

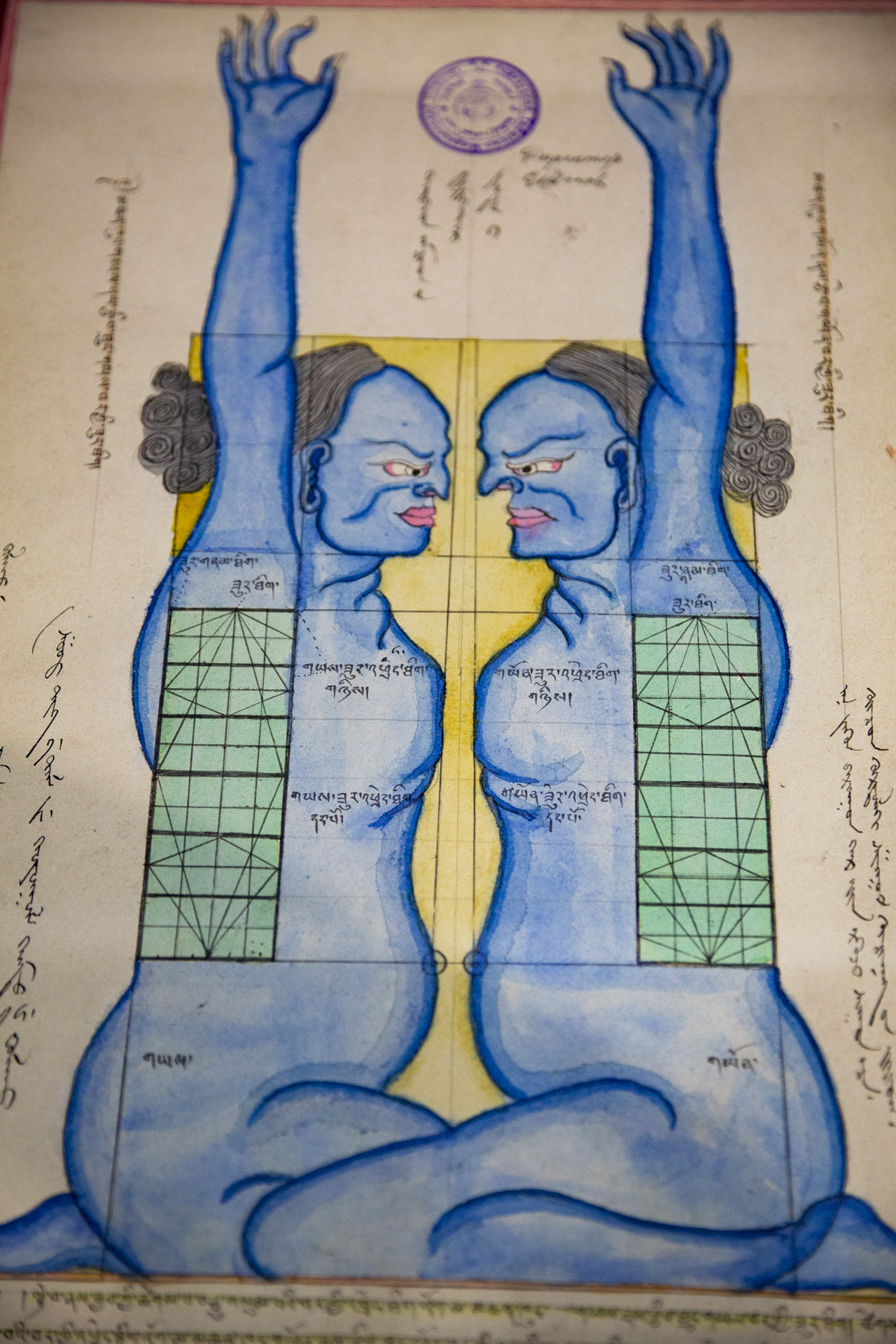

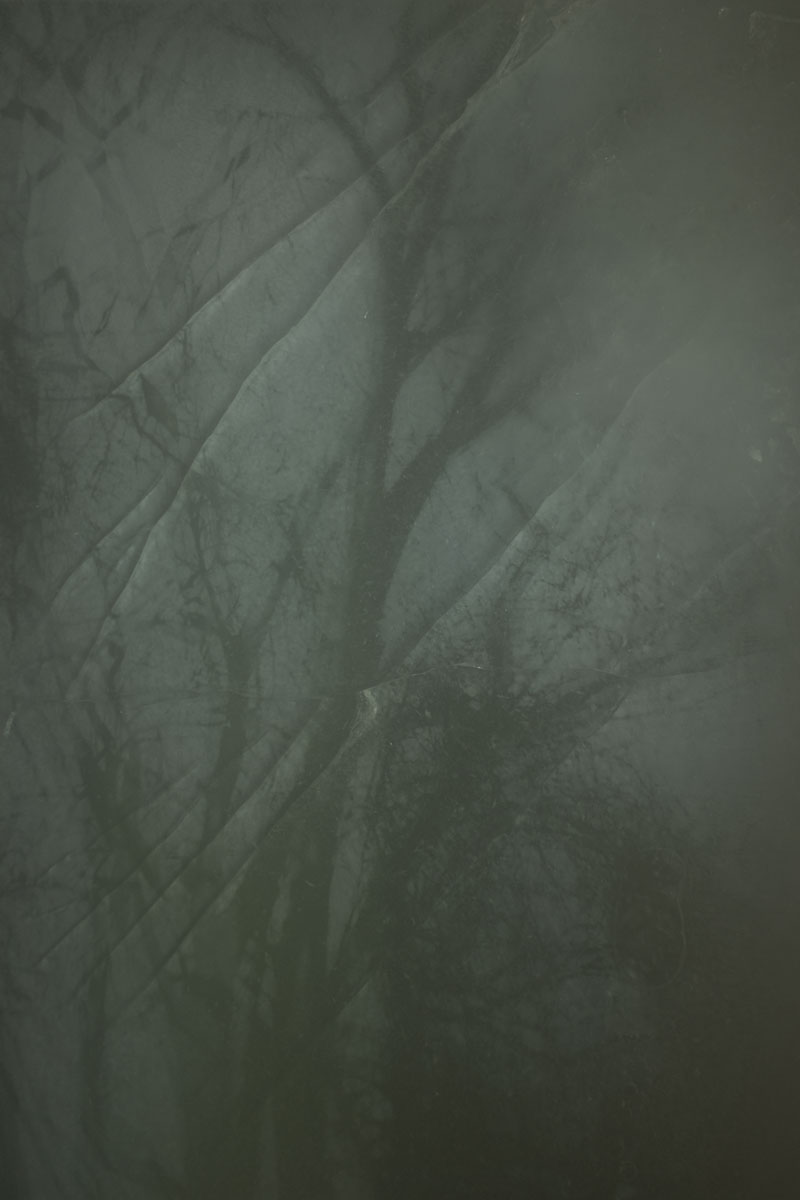

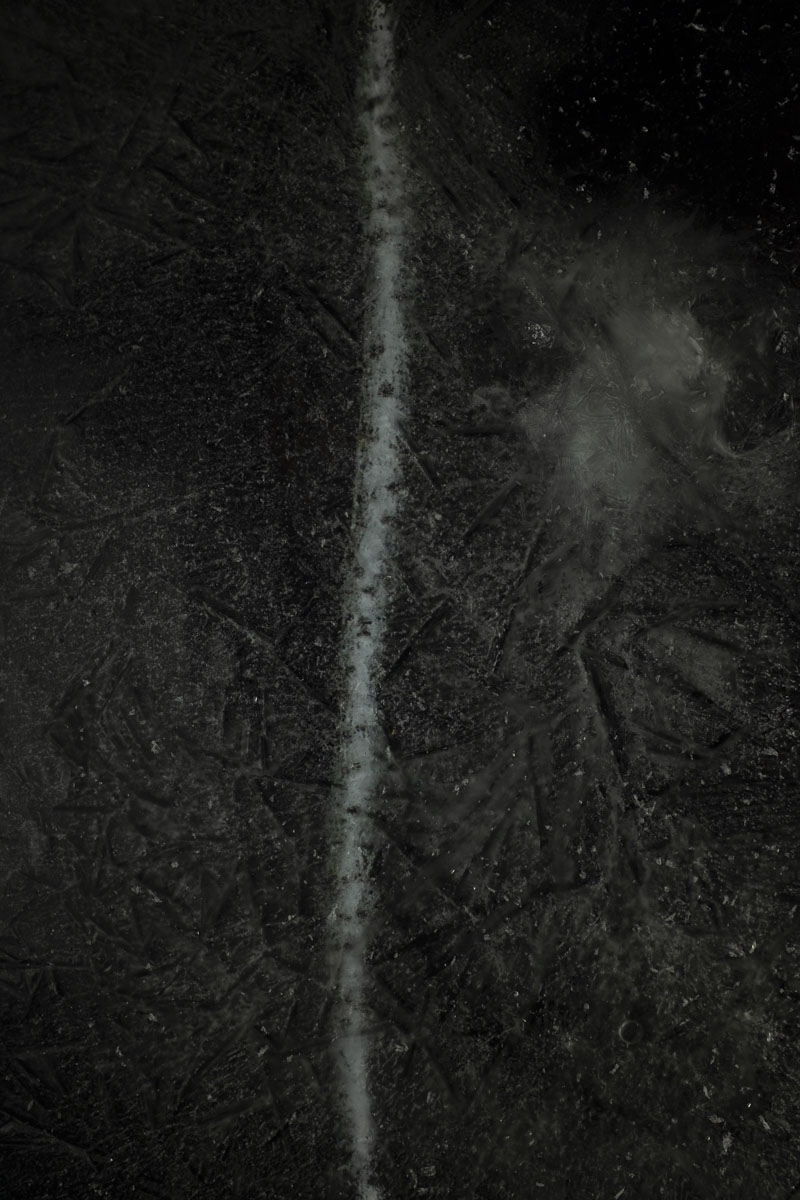

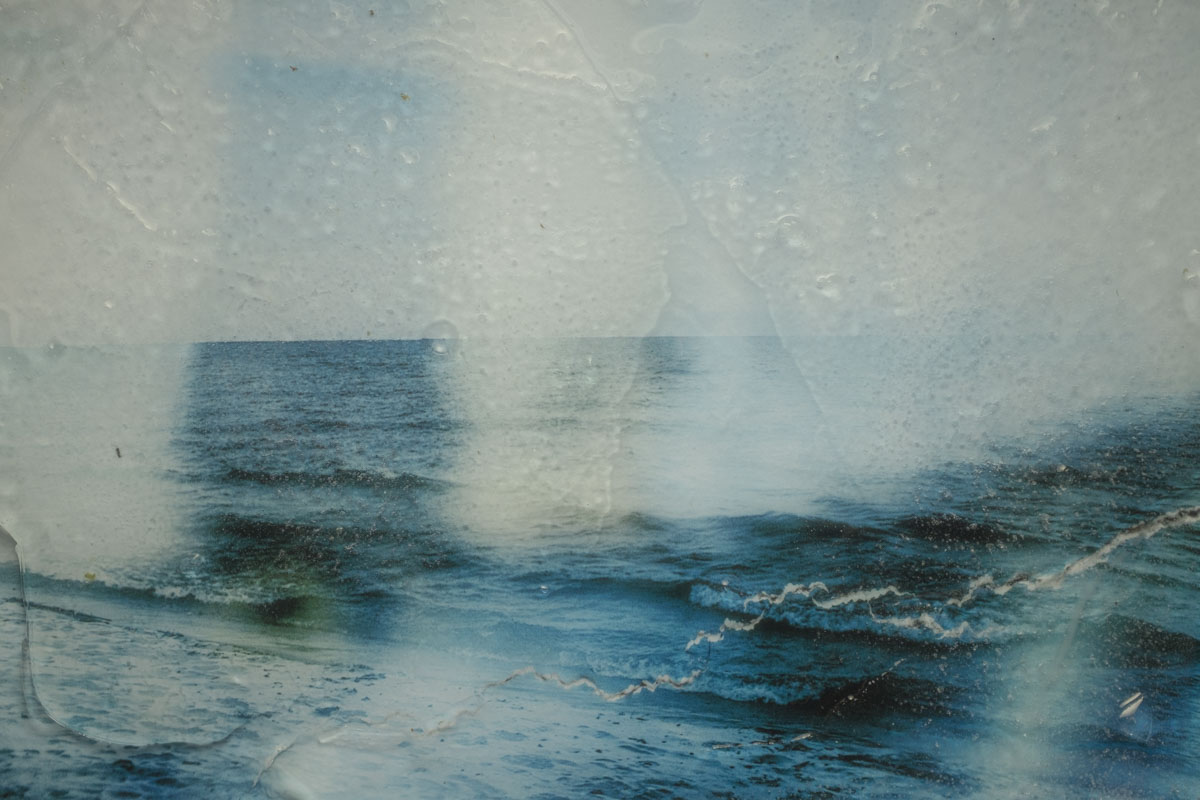

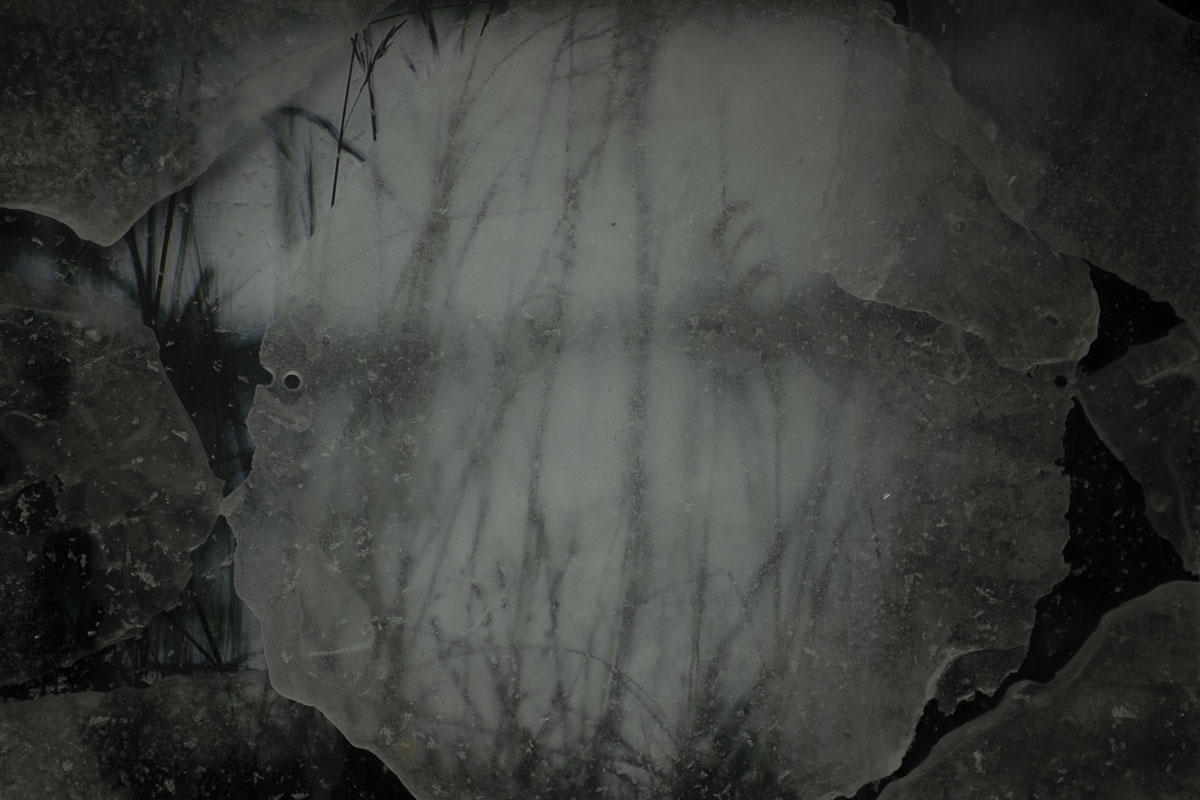

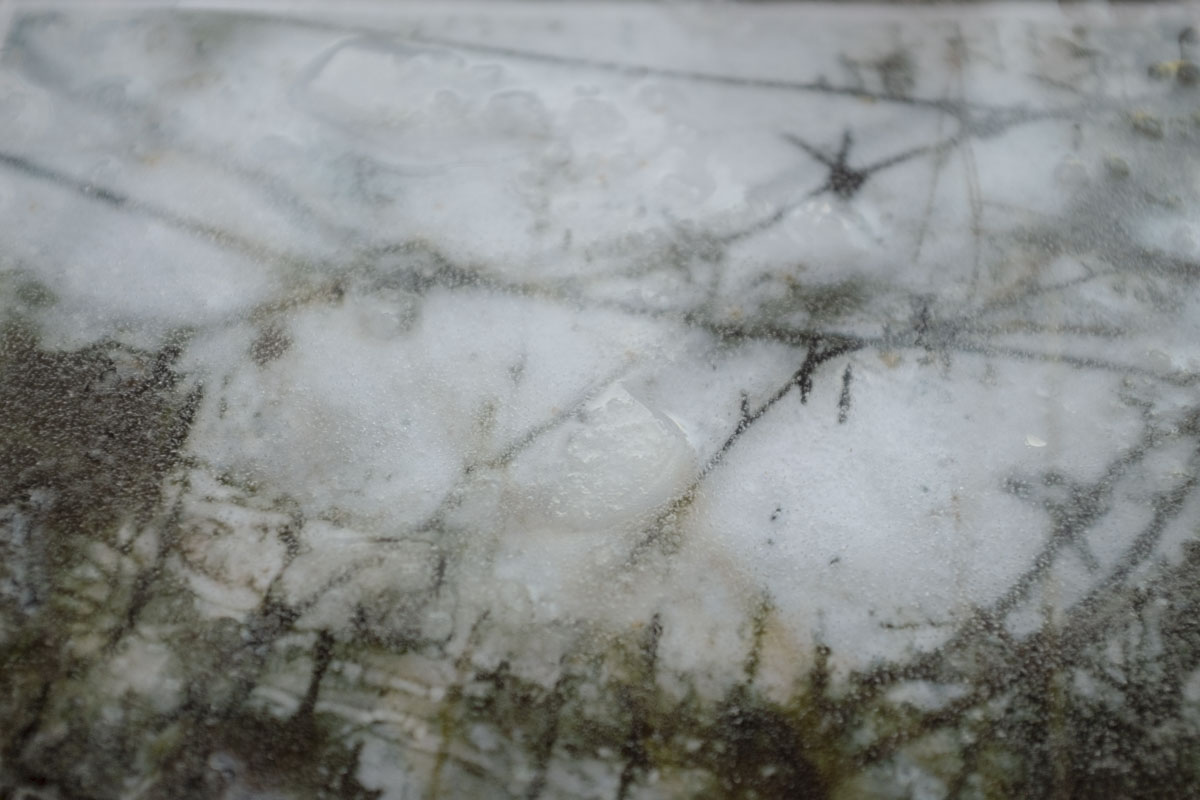

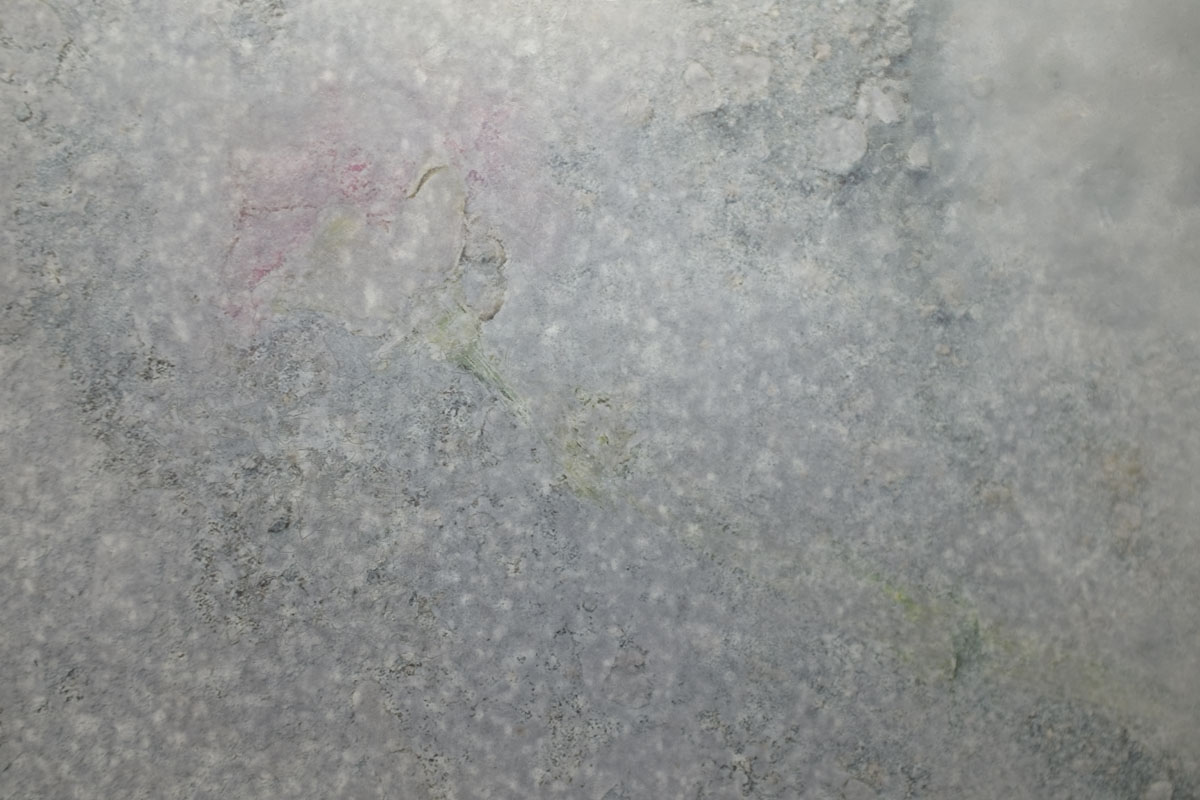

Shallow Frieze is a collection of experimental photographs that we created of Lake Baikal’s landscape that were frozen in ice and then rephotographed during a melting process. These photographs directly comment on the problem of global warming, which is occurring more rapidly in Siberia than most places in the world. Research by Russian and international scientists demonstrates that Baikal’s ice cover, critical to its many endemic species, is significantly shorter and thinner than a century ago. These warming trends are already contributing to changes in the Lake’s precious ecosystem, from tiny plankton to the world’s only freshwater seal.

It’s comforting to think of getting back to normal, but we’re already marooned somewhere quite distant from that. And rather than try to get back, we need to fight our way forward to a new place. Normal must be lashed, scraped, smashed, eliminated, excoriated, demolished.

And to do that, we need new paradigms, a leap forward, in our thinking. We got a glimpse of quieter, cleaner cities during lockdown. In the New York Times, Farhad Manjoo recently asked, "What about cities without cars?" Not as fanciful as we think, this solution has the potential to simultaneously clean the environment, save lives, expand park space, and improve health.

In the political realm, there’s always a tension between what we know we should do and what’s “politically realistic” given the power of the fossil fuel industry and its allies. But there’s considerable evidence now that the economy is moving faster than politicians. Recent studies show that solar and wind plants are already more economical, in every major market around the globe, than existing coal-fired plants. While regressive leaders cling to archaic paradigms in the hopes of solidifying their base and preserving dying jobs, a report issued in 2018 by, yes, the Trump Administration, makes it eminently clear that climate change could have a devastating impact on the American economy, eliminating as much as one-tenth of the nation’s GDP by the year 2100.

The Green New Deal is often criticized for being too sweeping and unrealistic in part because it links climate change to social justice issues. But isn’t that exactly what the pandemic demonstrates? “I can’t breathe” are not just the dying words of George Floyd on the streets of Minneapolis, but they are the words of people of color dying from COVID-19 in disproportionate numbers, and they are the words of poor and working class people who are more frequently exposed to contaminants and pollution in the environment, causing serious health problems and premature death. (If this sounds like hyperbole, then be aware that more than 90 percent of people in the world breathe unhealthy air, causing 7 million deaths per year.)

Greta Thunberg is outspoken about the fairness issues at play in the climate crisis. She is quoted in Time Magazine recently saying,

On average the CO2 emissions from one single Swede annually is the equivalent of 110 people from Mali in West Africa….The vast majority of the global population...are already living within the planetary boundaries….The climate and sustainability crisis is not a fair crisis. The ones who’ll be hit hardest from its consequences are often the ones who have done the least to cause the problem in the first place.

And while we all need to do our part and be willing to compromise on our lifestyle to limit greenhouse gas emissions, there’s a firm case to be made that the rich have outsized impacts, and need to be at the head of the line in making changes. Around the world, regardless of country, the wealthy often own several large houses, drive multiple cars long distance, fly frequently, and use energy at a rapid clip. As British scientist Kevin Anderson put it in the Guardian recently, “Globally the wealthiest 10% are responsible for half of all emissions, the wealthiest 20% for 70% of emissions.”

If the rich were forced to cut their emissions to the level of an average citizen, Anderson estimates, we could cut greenhouse emissions by one-third. The catch, of course, is that wealthier citizens, industry leaders and top policymakers are among the most powerful and don’t easily embrace far-reaching changes, choosing to sublimate the fact that their own children are the ones who will be paying the proverbial piper. Anderson says, “Many senior academics, senior policymakers...have decided that it is unhelpful to rock the status quo boat and therefore choose to work within that political paradigm – they’ll push it as hard as they think it can go, but they repeatedly step back from questioning the paradigm itself.”

If climate change is not just an environmental issue, but a social justice issue, it forces us to consider how to claim more power so we can accelerate change. Recent history in the United States sadly does not suggest we’re good at maintaining meaningful movements. After all, what happened to Occupy Wall Street, The Women’s March, the March for Our Lives on gun violence, etc.? We don’t hear much about them anymore.

But it’s possible we’re in the middle of something a tad different. The Black Lives Matter protests, which occurred in hundreds of cities across America, are variously estimated to have included between 6 and 10 percent of all Americans, making it potentially the largest protest movement in US history. (That’s not counting the many solidarity protests abroad, including the one we joined in Bratislava, Slovakia.)

Thousands gather for a Black Lives Matter solidarity protest in Bratislava, Slovakia, on June 13, 2020. Peaceful protesters gathered at the Square of the Slovak National Uprising, an important historic spot related to the fight against fascism, and marched to the US Embassy, where they heard speeches from African-Americans living in Slovakia and musical performances.

Although we don’t have the same revered leaders as we did in the 1960s in the heyday of the Civil Rights movement, we can learn from their strategies. Dr. Martin Luther King, for example, was indefatigable in pursuing protest and non-violent civil disobedience to demand and bring about lasting change. Less known is the fact that King himself was one of the first to closely link social justice and environmental justice issues. Now we need to follow through on Black Lives Matter, making desperately-needed and long overdue change in our criminal justice system, but we also need to go further, sustaining a long-term movement around environmental and economic justice.

Yes, we all need to vote, the presidency is especially important this time around. Just think about the American response to coronavirus, in which the president gathered fossil fuel moguls suffering from reduced demand and promised them he’s with them 1000 percent, versus the EU, which quickly pledged $800 billion to rebuild their economies differently. But our problems are too big to be resolved by one election. We must join our voices, create a lasting movement, and pursue paradigm-shifting changes through ballots, sustained protest and King’s (and Gandhi’s) powerful method of civil disobedience.

There’s not a single thoughtful person who can’t step up their game, at least a tiny bit, during this demanding time. And artists, who can be meaningful influencers, are among those who have a responsibility to lead the way. Leaving room for a wide variety of approaches, Atlantika Collective has long prided itself on embracing a contemporary humanism and tackling socially conscious issues. In this time of coronavirus, Black Lives Matter, climate change and other pressing issues, you’ll see us take on more in this regard. You’ll also see some of us embracing direct action to accomplish change instead of relying solely on our artwork. Difficult times challenge us to do more.

It’s tempting to freeze up and go back to the way things were. But this may be the most important moment in our lives. We must demand a share of power big enough to enact cathartic, transformational change: to eradicate the impact of racism in our justice system, revolutionize our environmental paradigm and save the planet. We must act and believe as if the politically impractical is not only possible but imperative. We must do this with rigor, consistency and perseverance. Only then will we wake up to a nation that is democratic and just -- and an economy that is clean, prosperous and fair.