Gabriela Bulisova & Mark Isaac

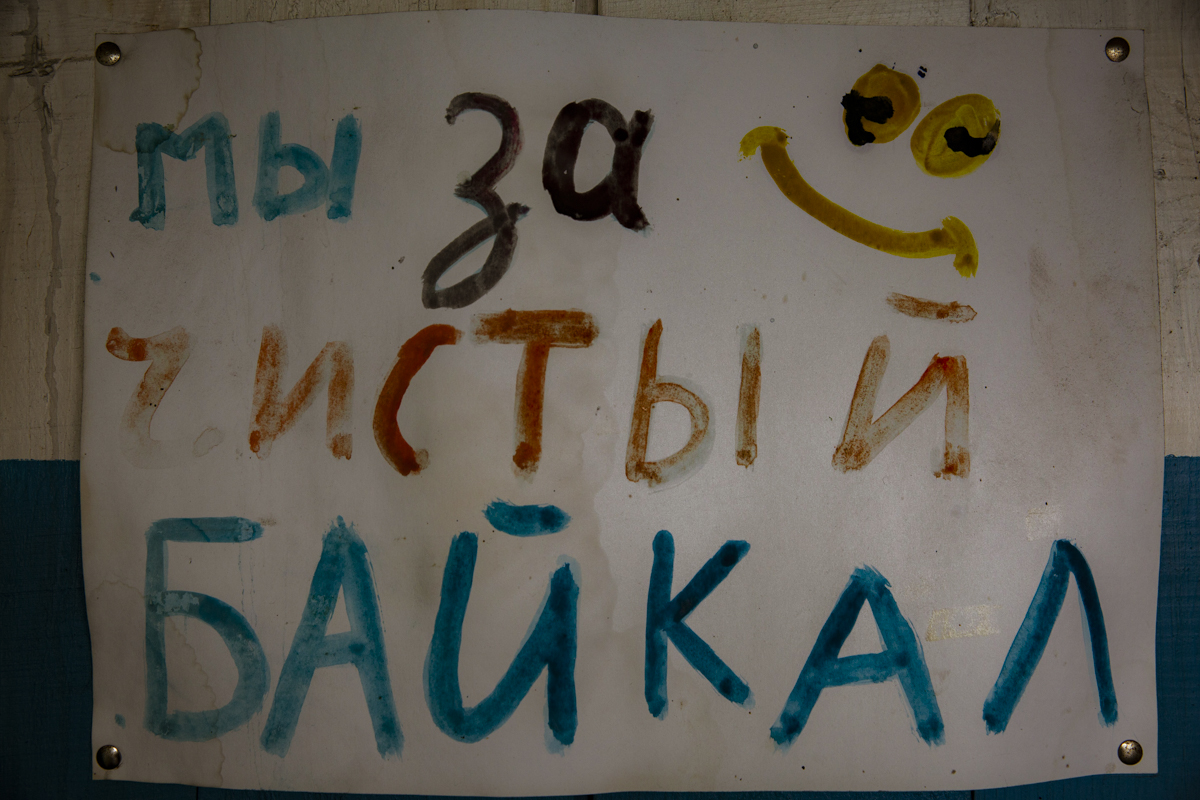

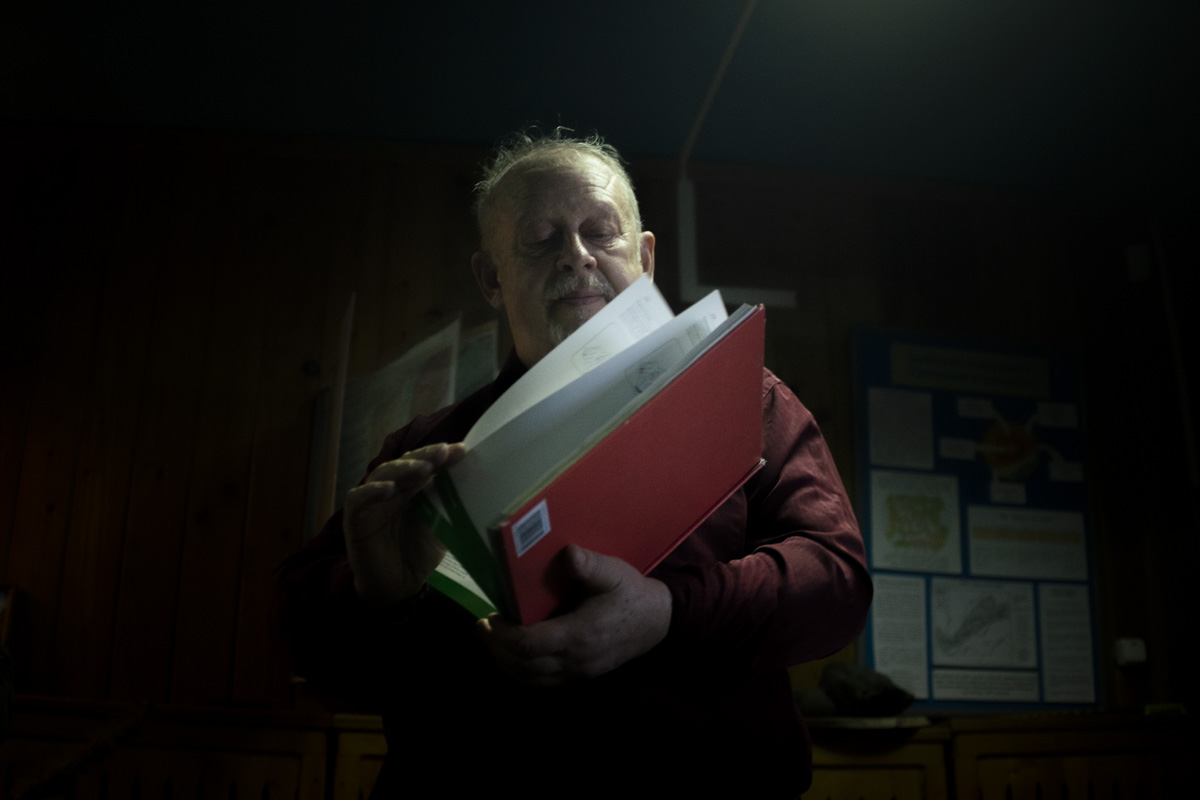

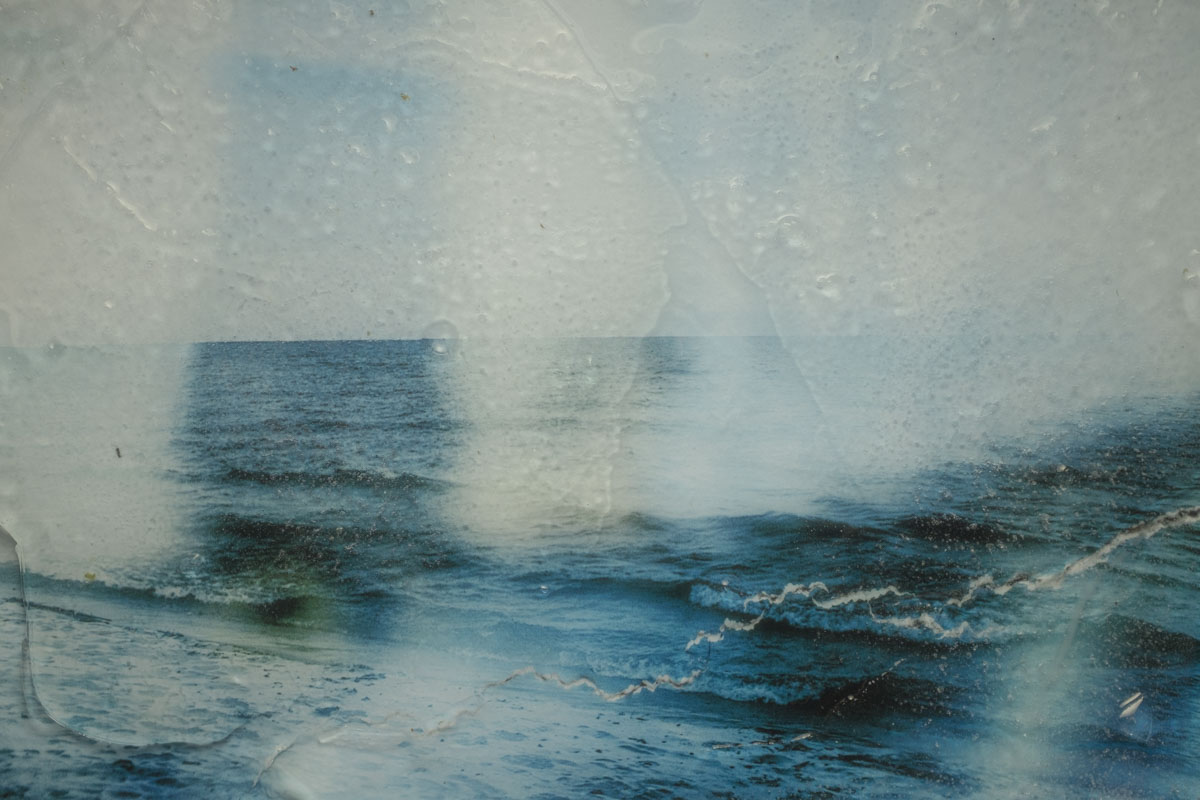

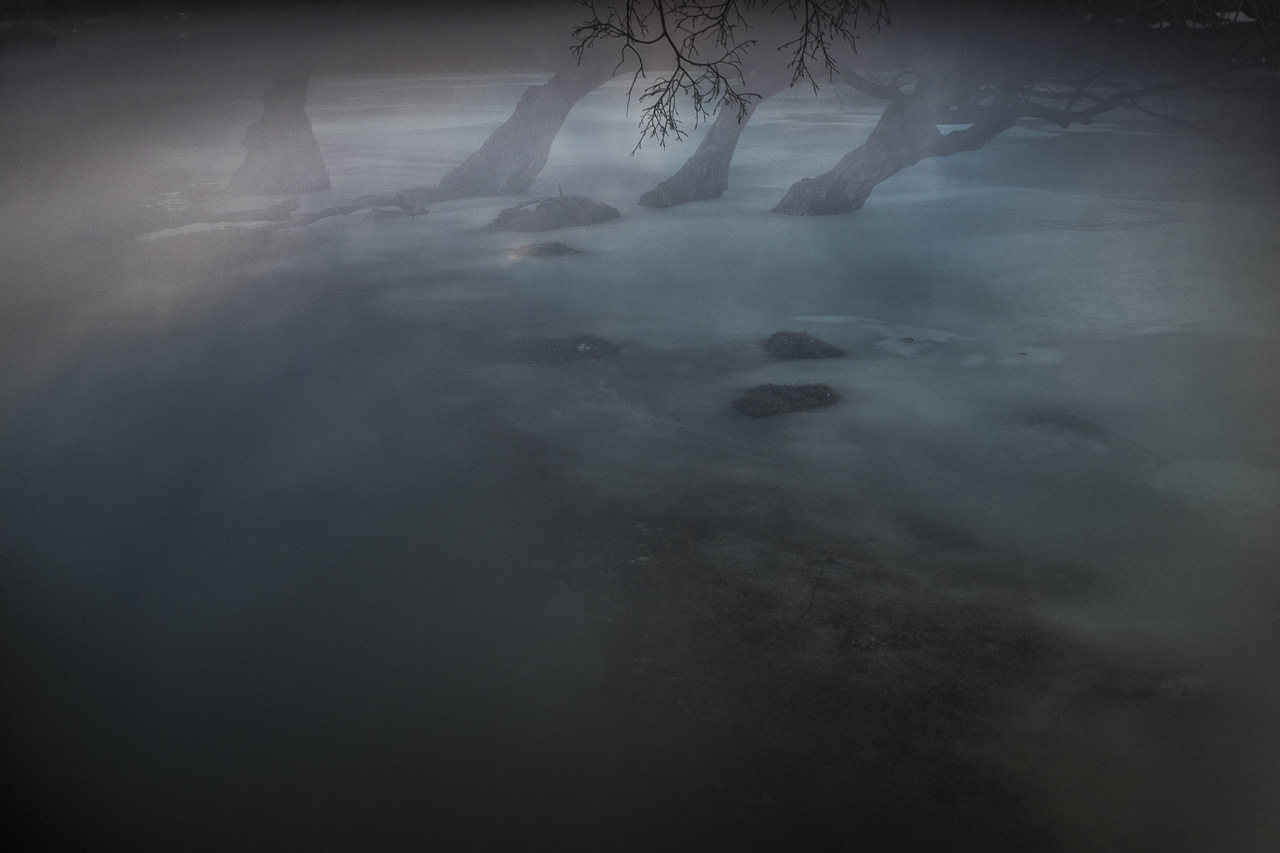

During our sojourn in Siberia, one of the most important tools we used to depict Lake Baikal was multi-channel video. The Second Fire, which was screened in Irkutsk’s Bronshteyn Gallery in late Summer, is a three channel video that focuses on the impact of climate change and pollution on the Lake. A Russian student described it as “truly frightening.” If it scares her and her classmates into action, we will take it as a compliment.

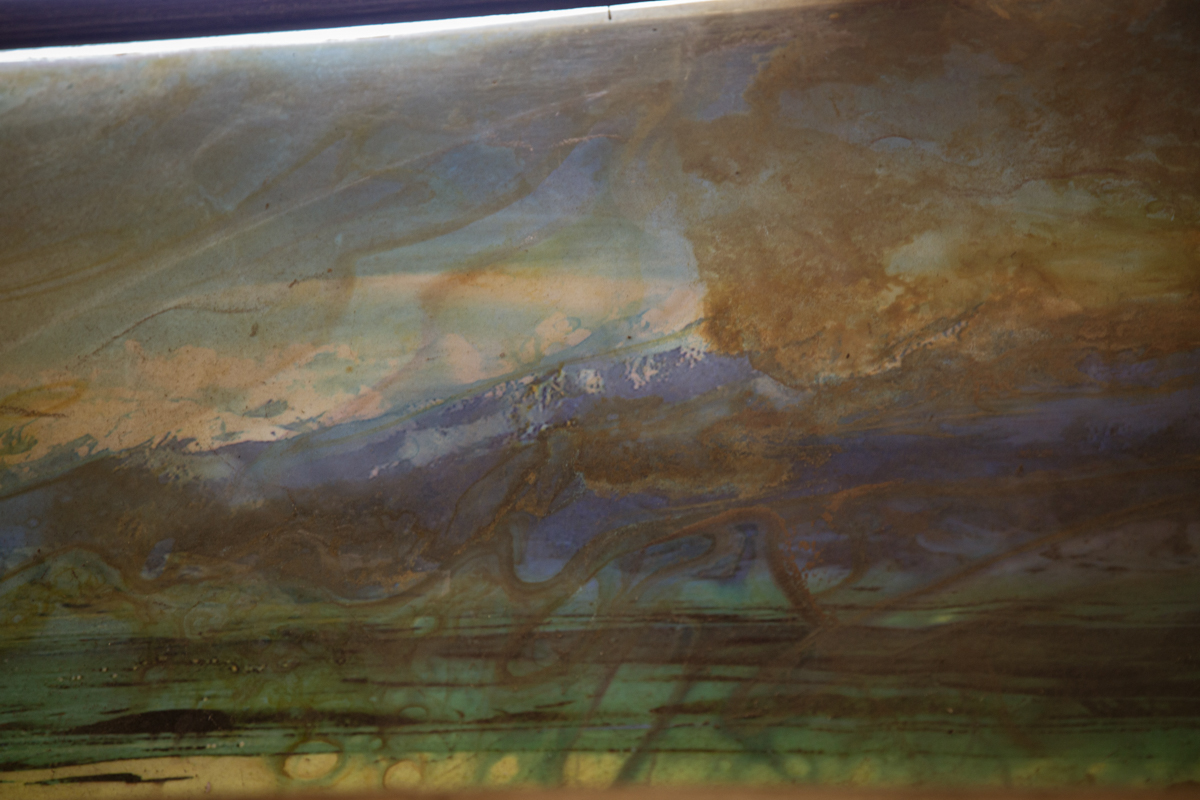

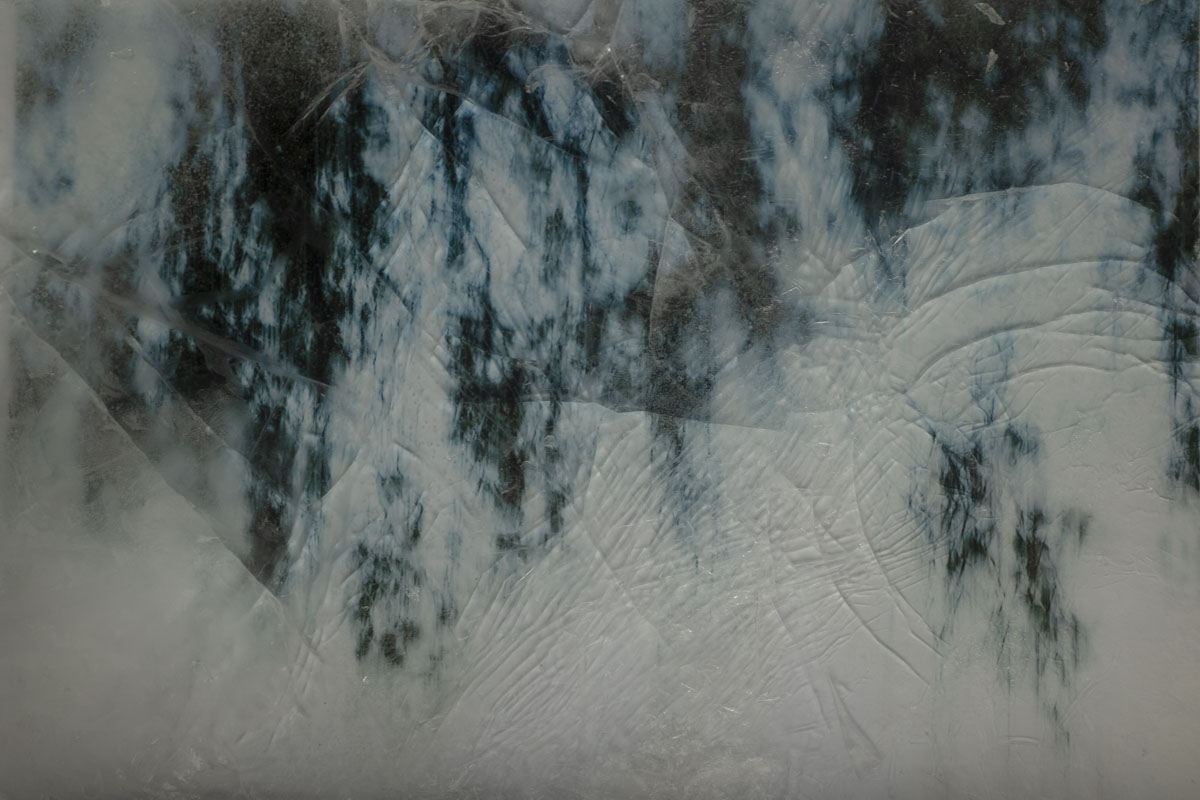

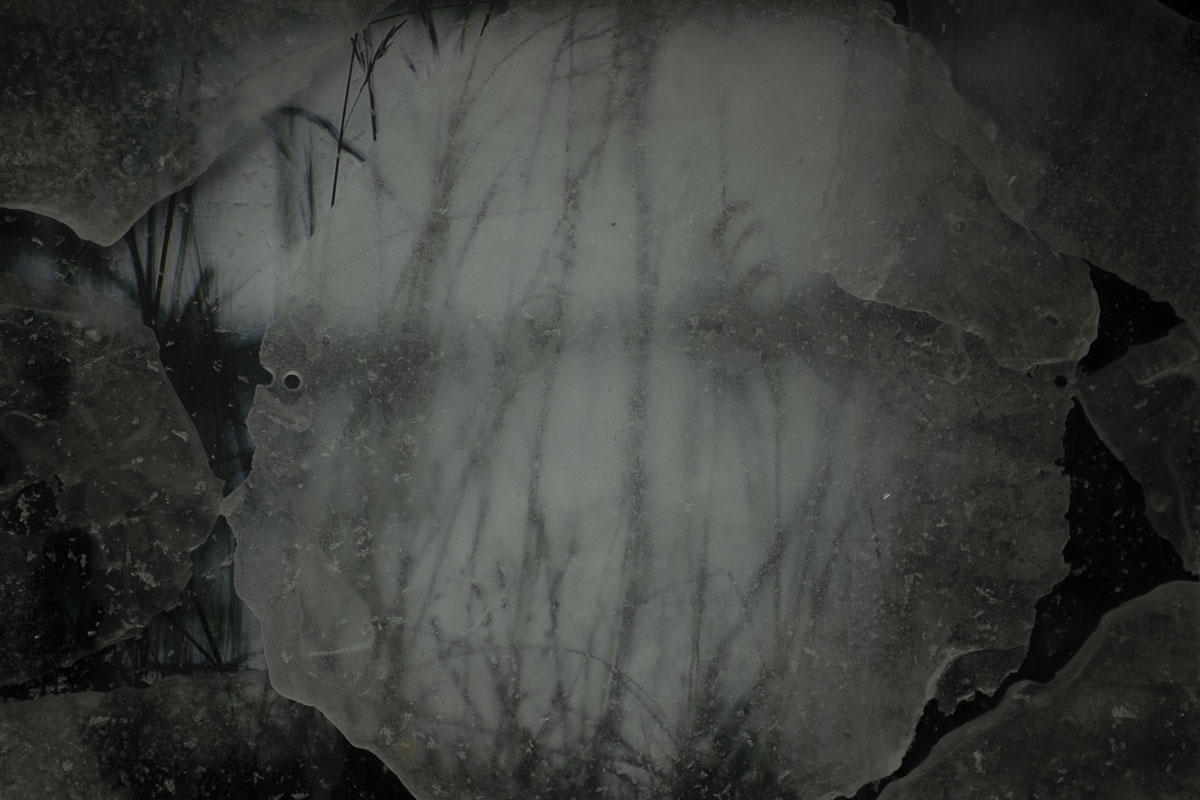

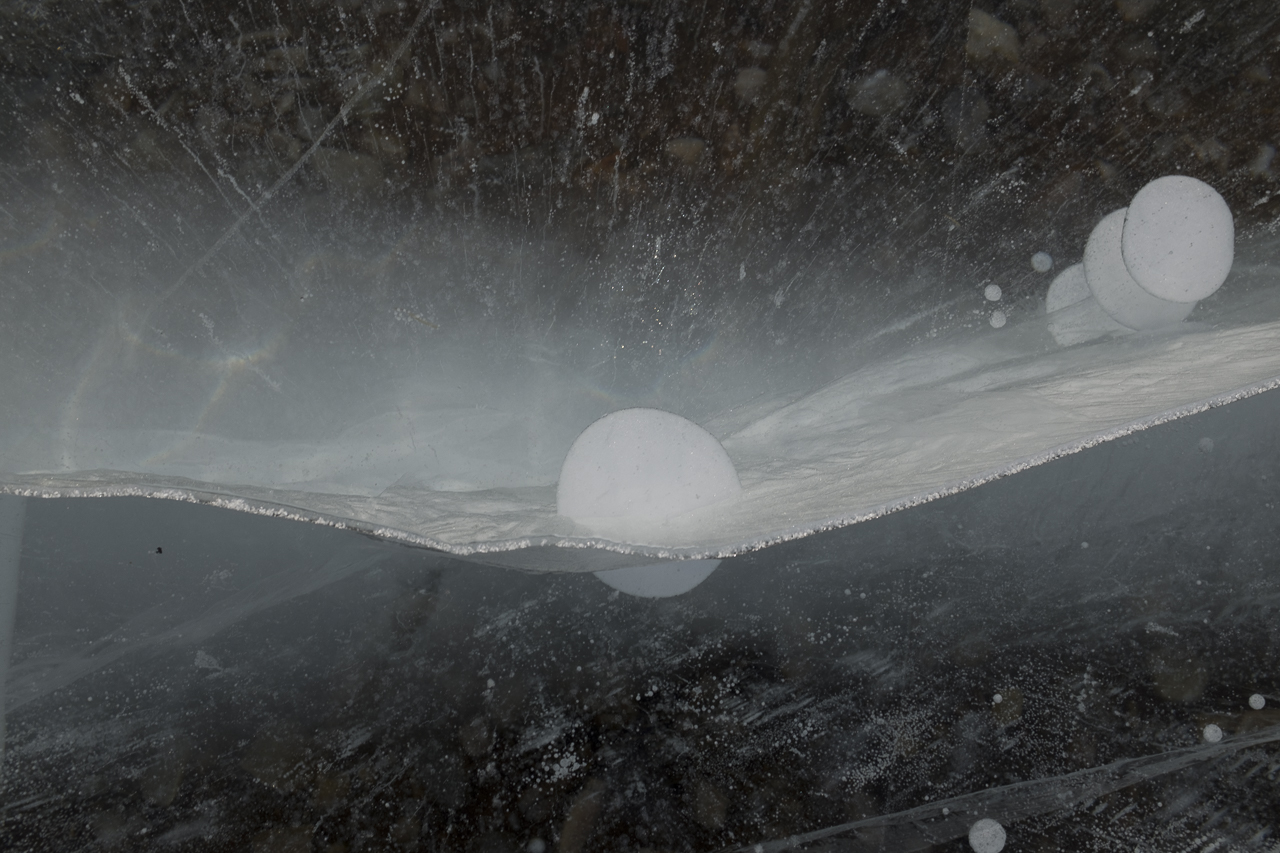

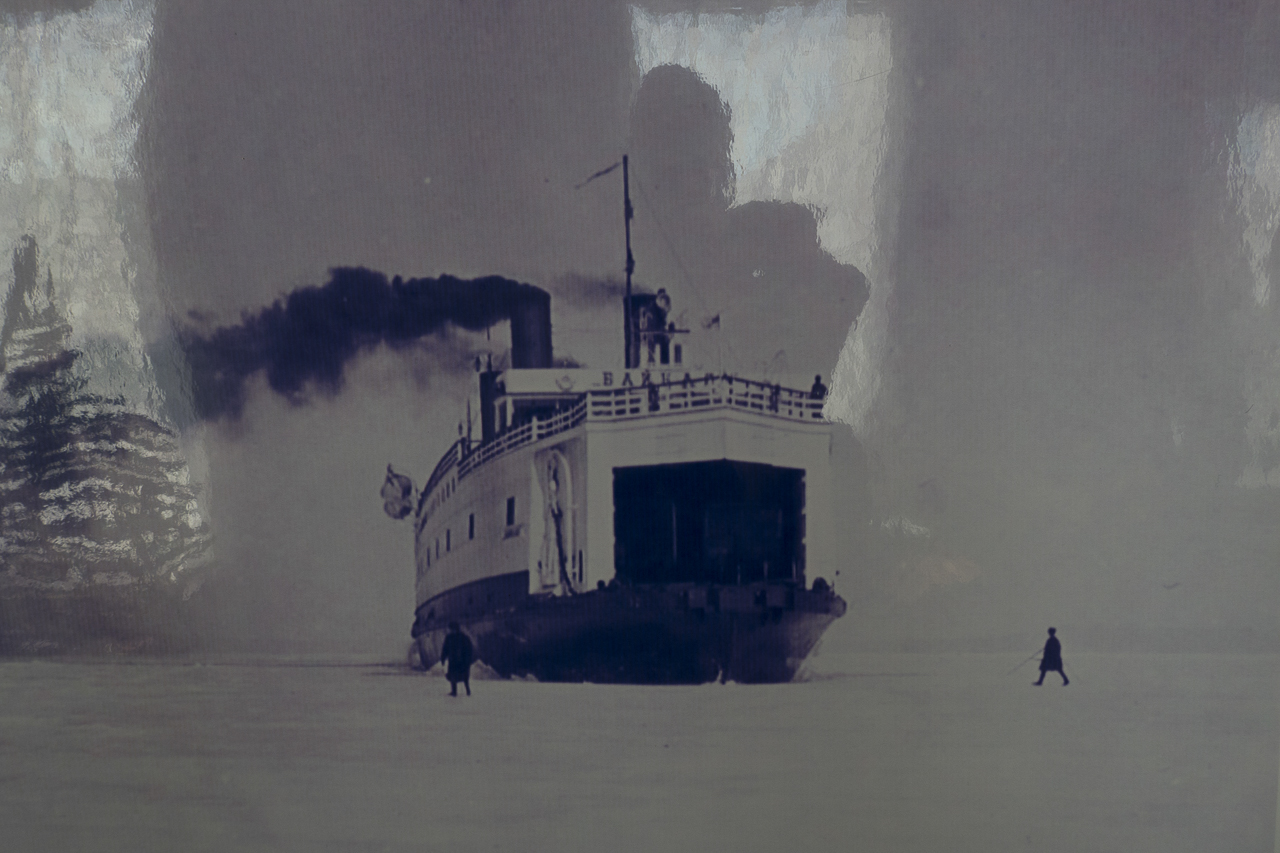

The Second Fire is inspired by a native Buryat legend about Lake Baikal. According to this origin myth, there was an enormous earthquake, fire came out of the earth, and native people cried “Bai, Gal!” or “Fire, stop!” in the Buryat language. The fire stopped, and water filled the crevice, creating the Sacred Sea. Now, the Baikal region is one of the areas experiencing the most rapid increases in temperature in the world. The video suggests that the warming of Baikal is a “Second Fire” that threatens the Lake and the people who rely on it.

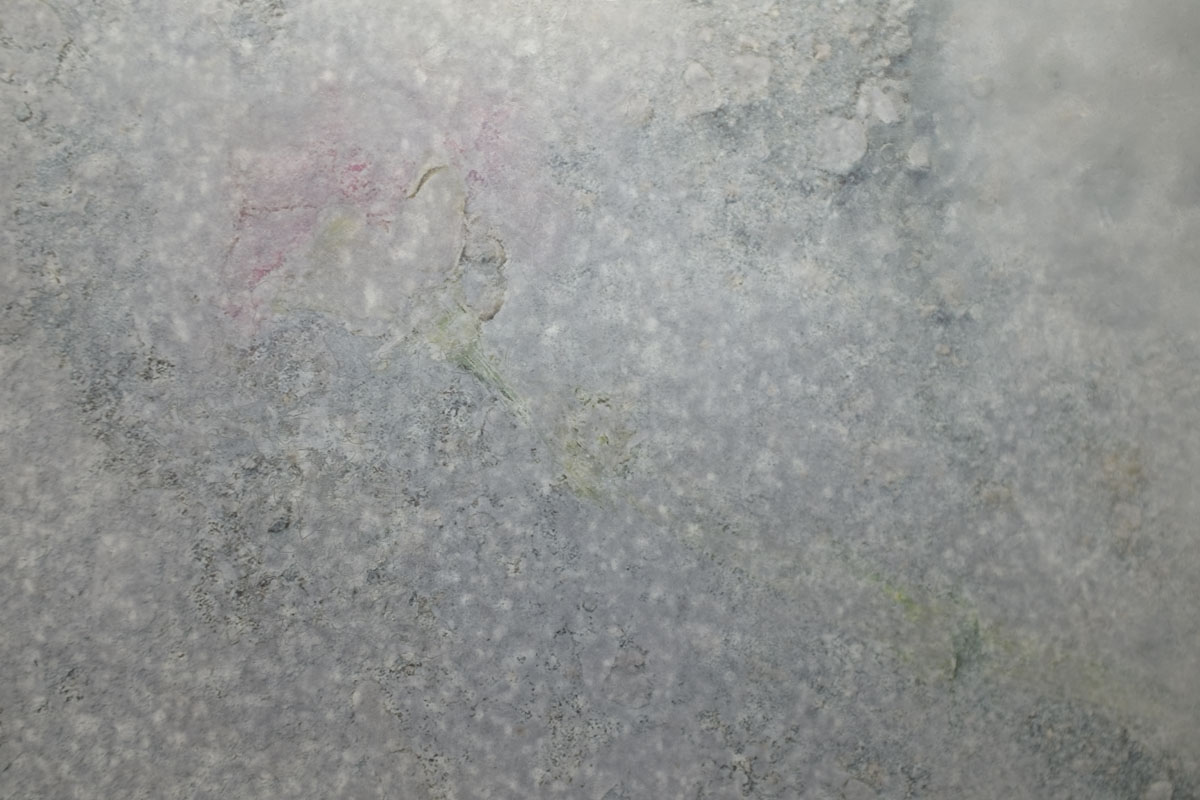

Now, we’ve produced a sequel...another three-channel video, called Embers and Effluents. This video goes beyond the most obvious challenges that Baikal faces to depict emerging threats that have the capacity to create a “feedback effect,” rapidly accelerating warming and environmental damage. Scientists know that these threats are approaching a tipping point more quickly than current climate modeling anticipates.

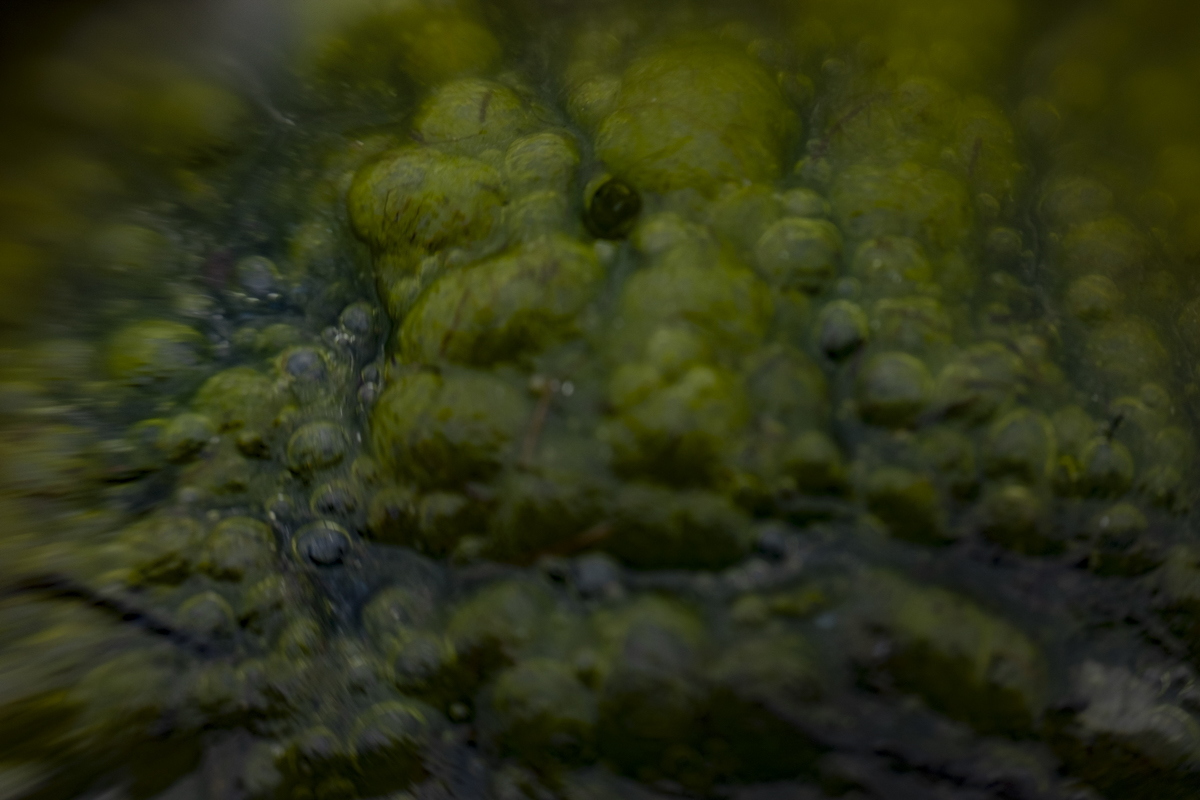

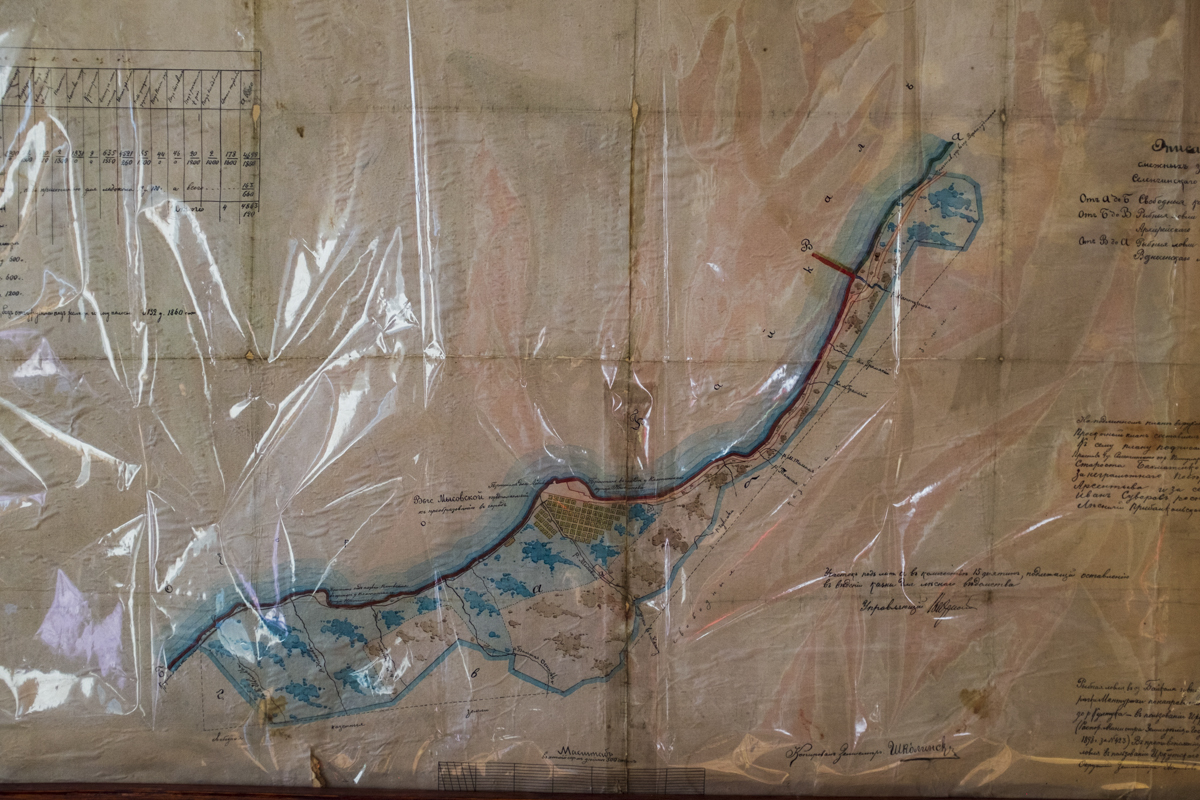

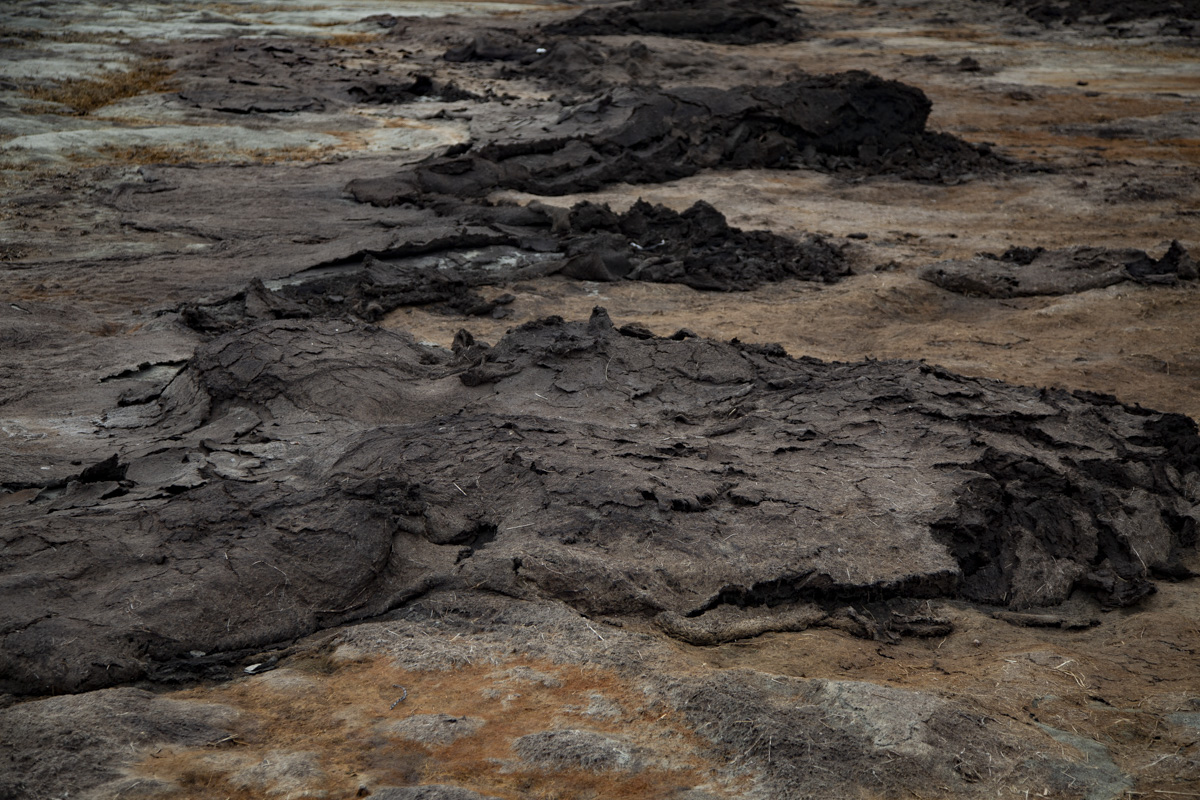

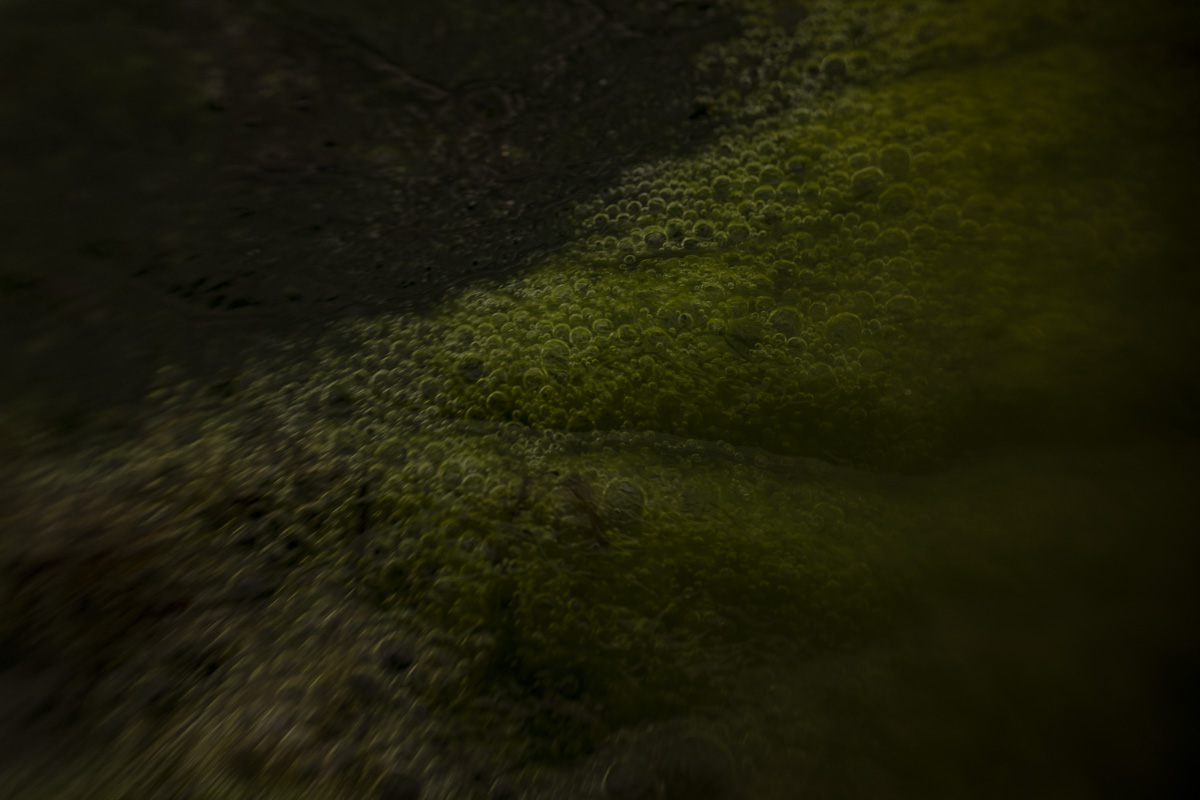

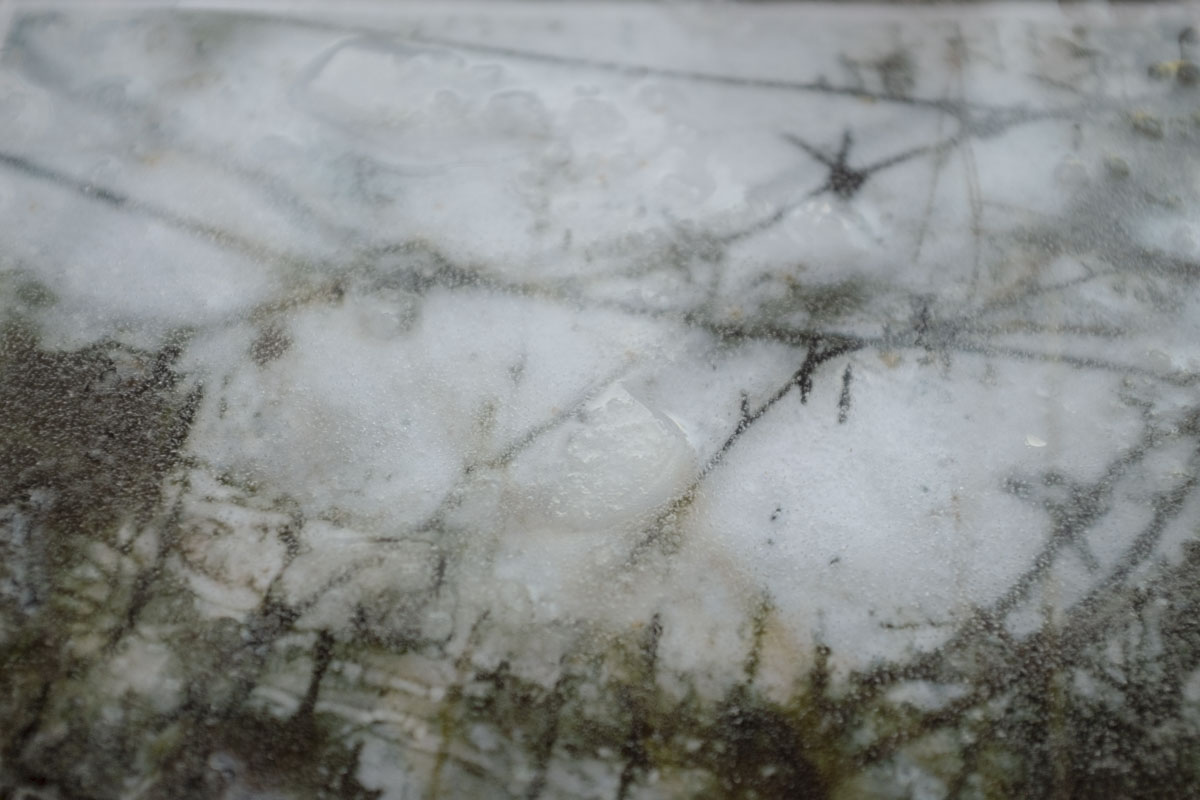

Vast territories of previously frozen permafrost are melting, discharging enormous quantities of carbon dioxide and methane. Rampant summer wildfires are causing dramatic loss of forested area. Widespread legal and illegal logging is also contributing to rapid deforestation. And as temperatures increase, the flow of the Lake’s tributaries is dwindling, reducing water quality and releasing additional methane.

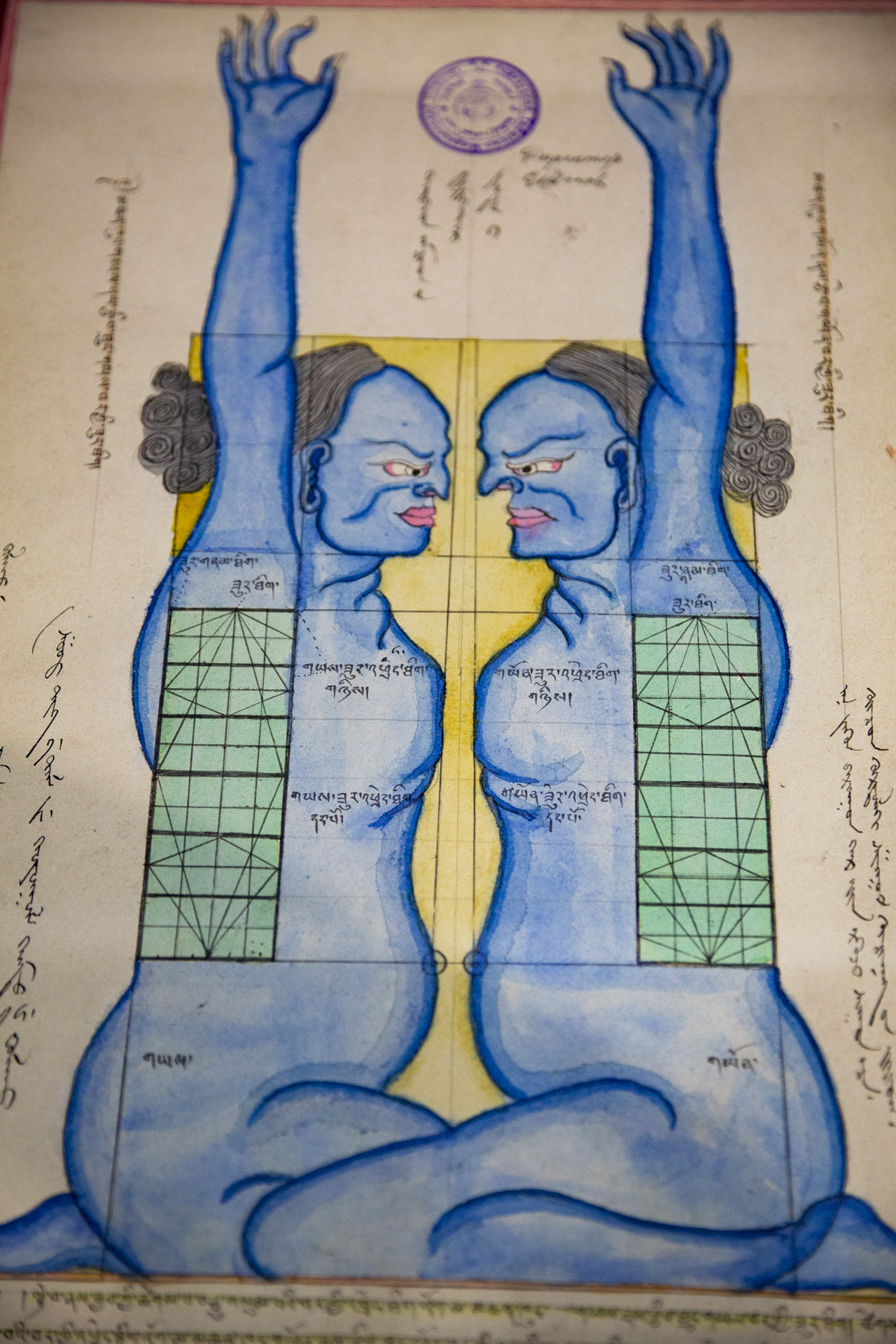

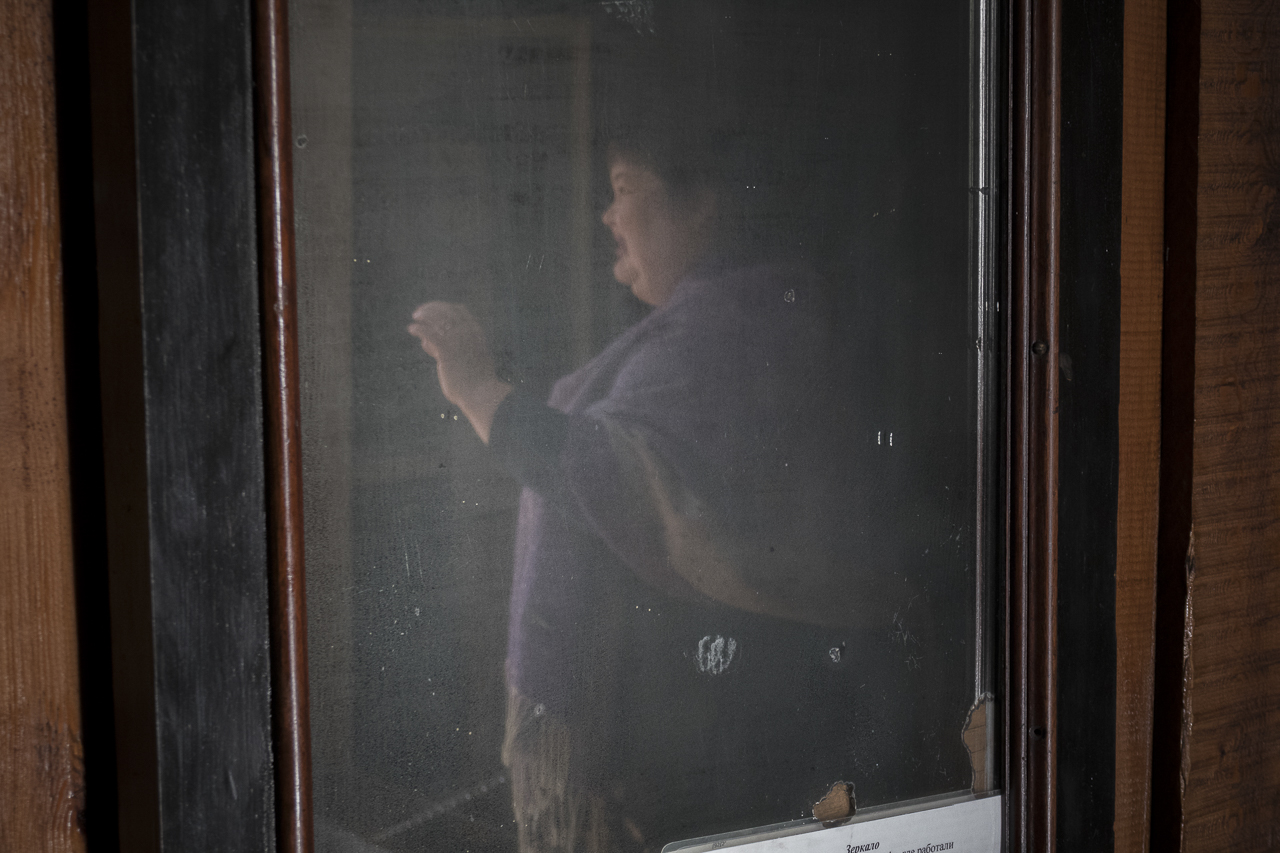

We were inspired greatly by the “environmental ethics” of Baikal’s first environmental stewards, native Buryats and Evenks. They lived in harmony with nature, taking only what they needed to survive. These indigenous people lived their lives in deep concert with the natural world long before the environmental movement developed in the West. Now, despite the serious threats that Baikal faces, the Siberian tradition of sustainability offers a reminder that we can restore balance in our relationship to the natural world.

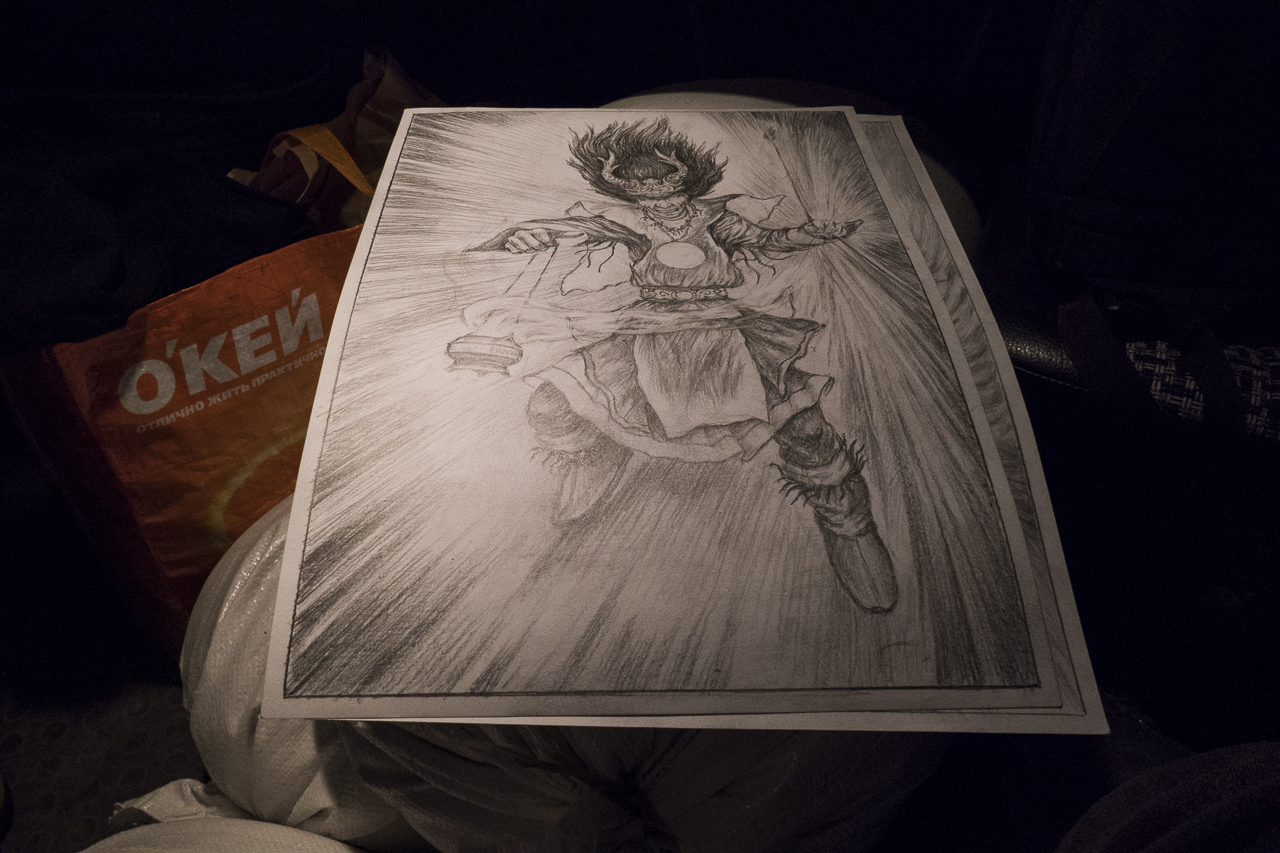

We witnessed and filmed multiple ceremonies of native Buryat shamans appealing to the gods for harmony and healing in the natural world. The shamans correctly insist that the Sacred Sea is powerful and resilient. But is this enough to turn things around? True hope will only emerge if the world is able to embrace transformational change, avoiding the feedback effect and the worst impacts of climate change and pollution.

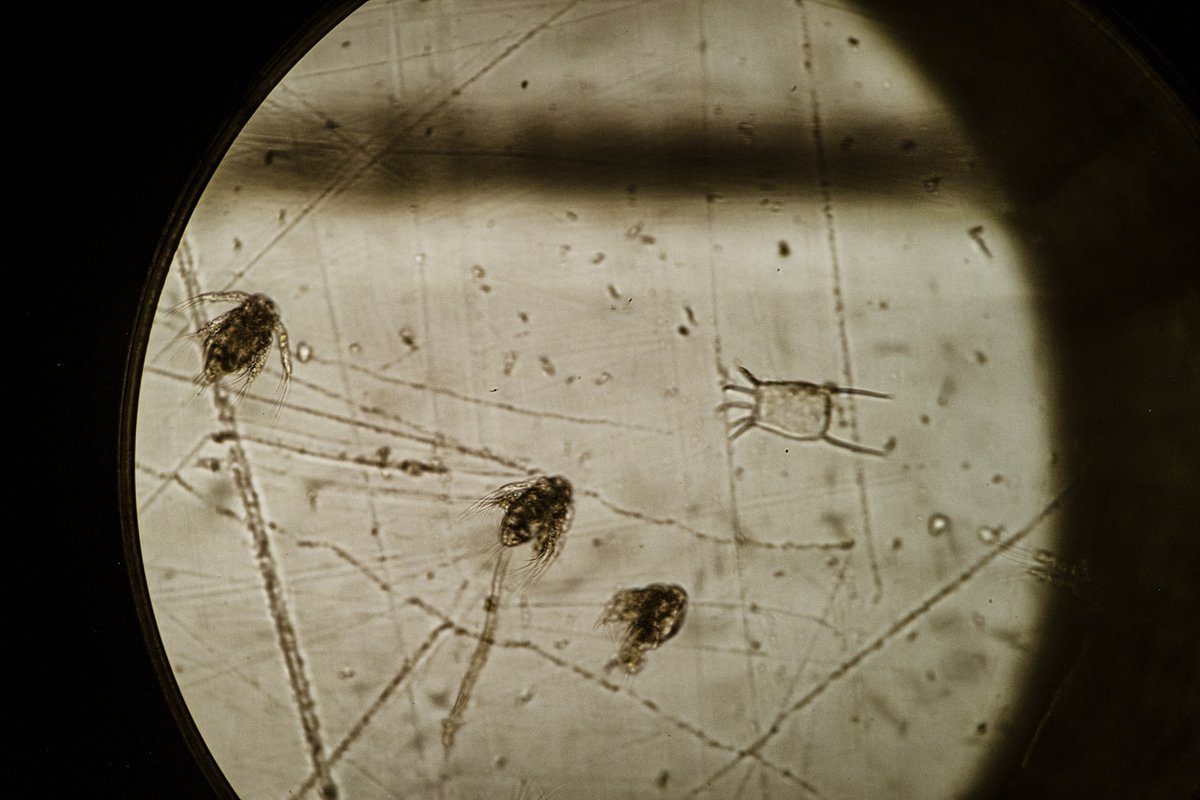

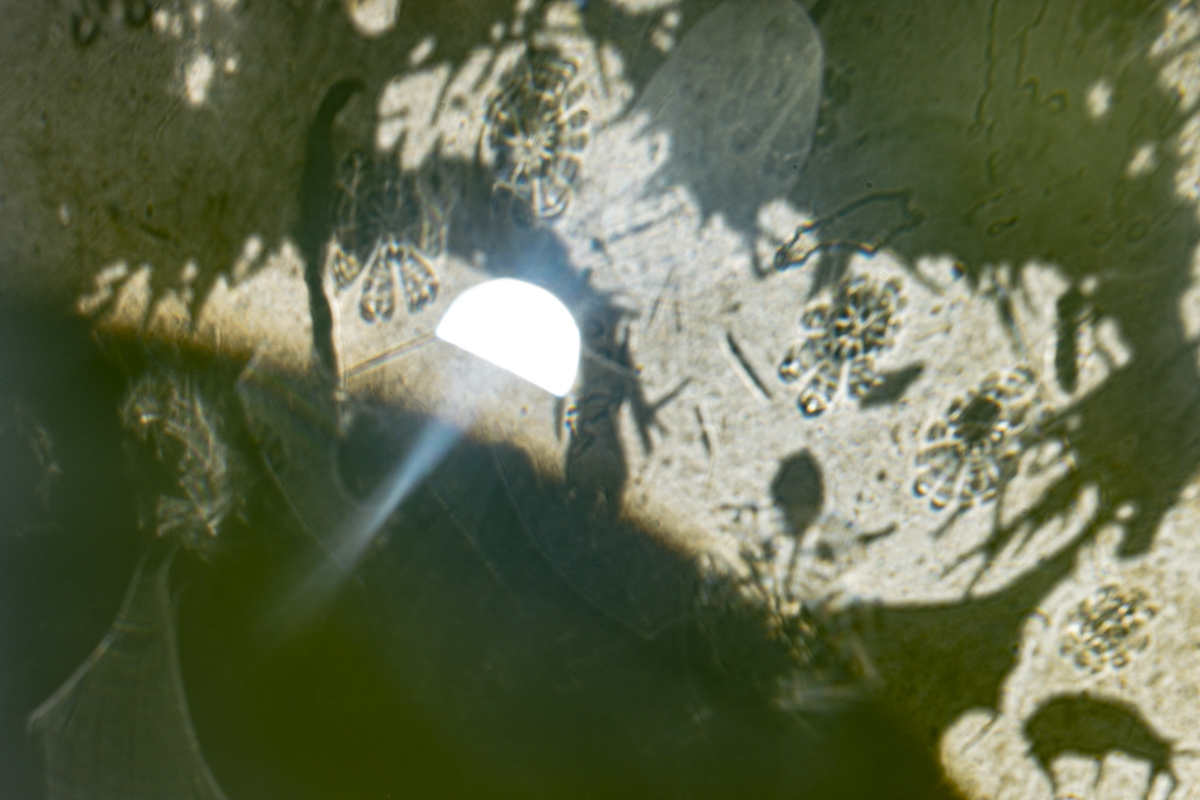

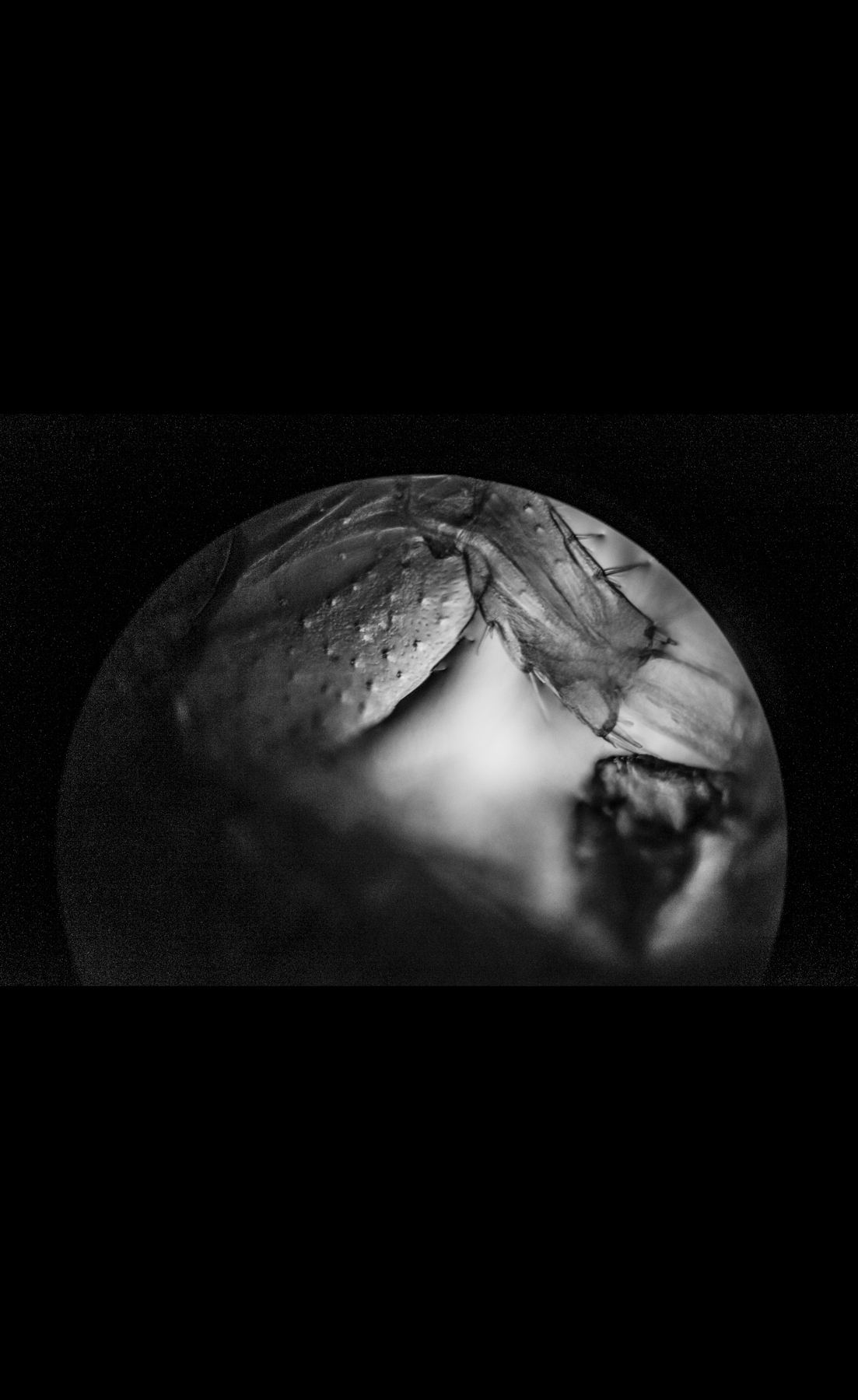

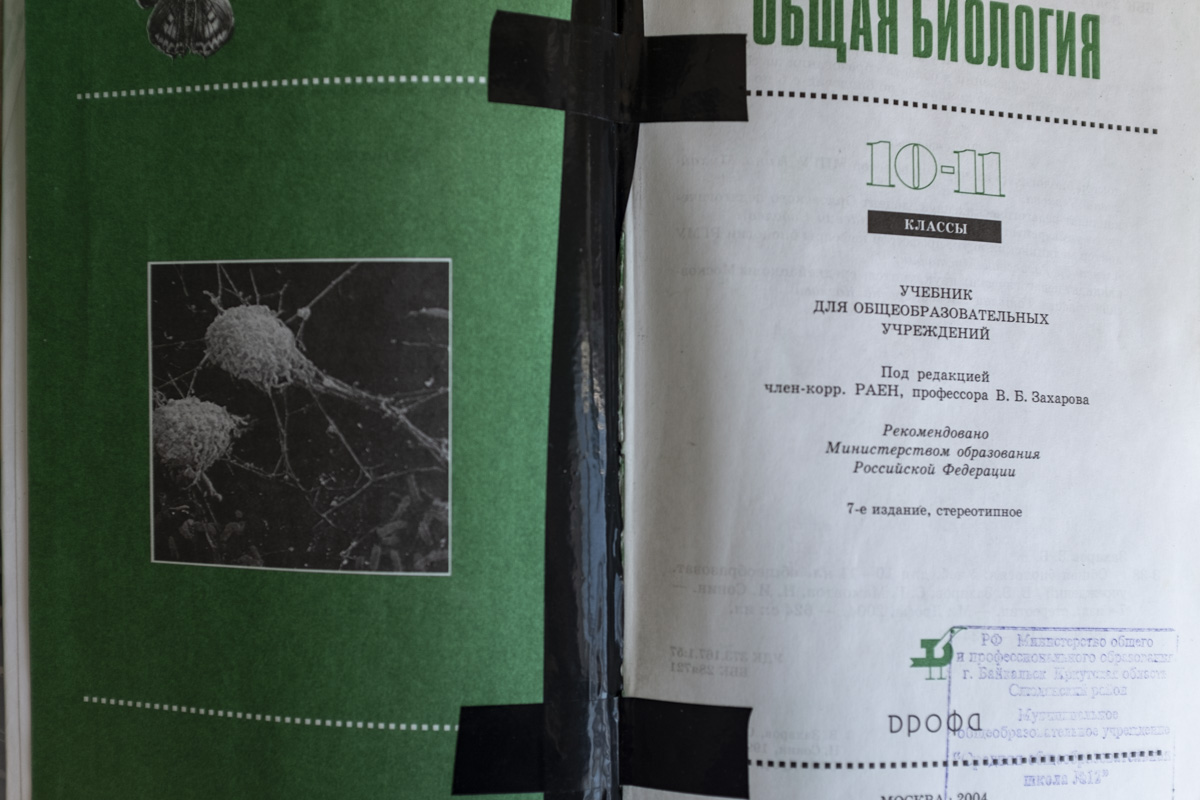

Like The Second Fire, our new video features original electronic music composed from scientific data about the impact of climate change on Lake Baikal. In particular, we used studies of the impact of temperature changes on some of Baikal’s smallest and most important organisms: tiny amphipods that inhabit the shallow banks, the deepest crevasses, and everywhere in between. The amphipods are heavily affected by temperature changes, and the film’s music gives them a voice that they wouldn’t otherwise have. As temperature data rises, the notes also rise and become more shrill, as if the amphipods are crying out for help.

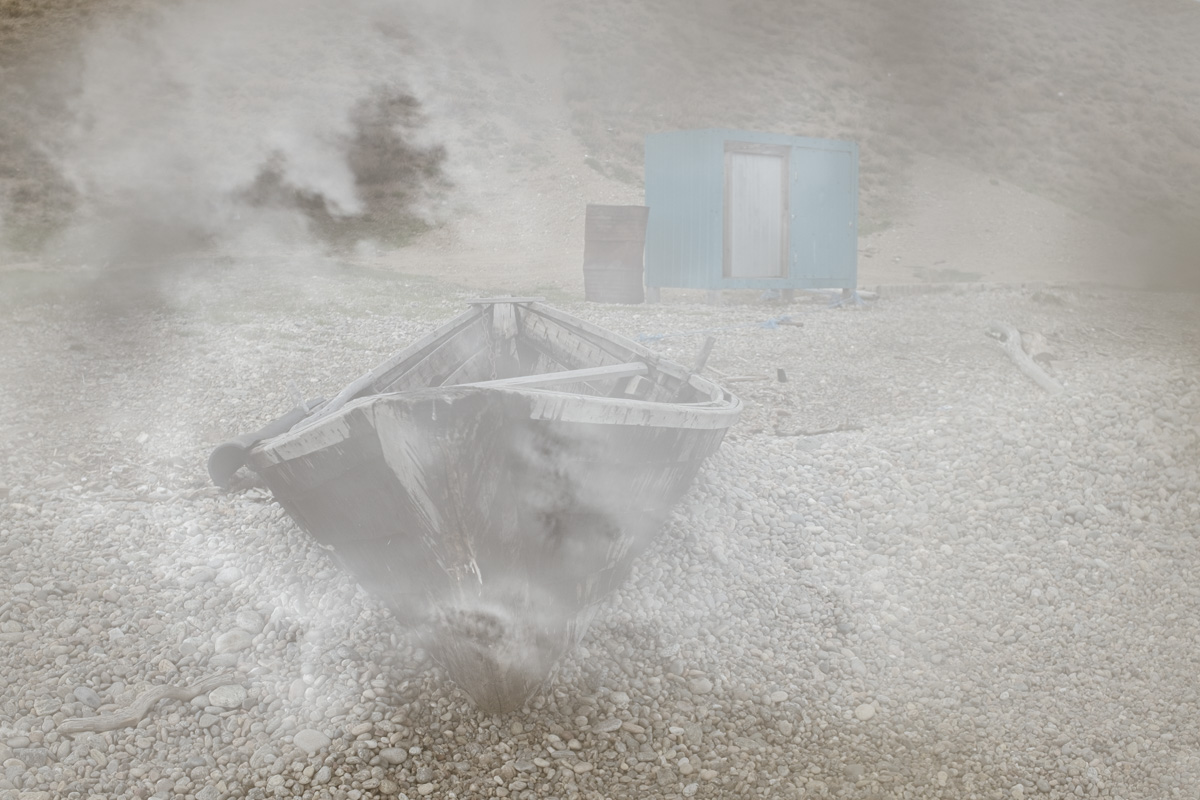

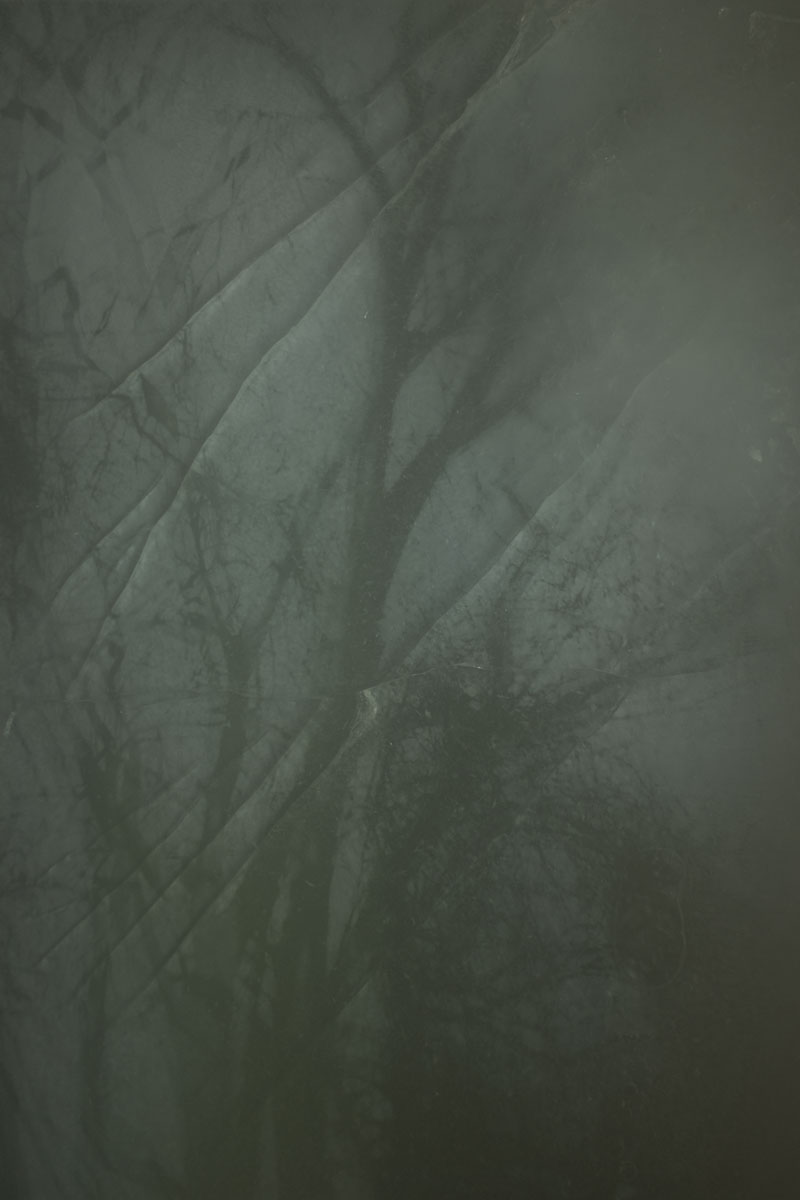

During our year in Siberia, we had almost daily encounters with the power and majesty of Baikal’s crystalline water, the looming white-capped mountain peaks that tower over its banks, and the endless forests that surround it. But we also witnessed endless trucks and trains hauling away the taiga’s precious trees. We breathed in the smoke from raging forest fires and witnessed the charred remnants of past fires. We photographed piles of rotting algae on the beaches, and we documented the shriveled banks of tributary rivers, running dry from the heat.

That is our choice now: reverse course and care for Baikal sustainably -- or resign ourselves to a future of embers and effluents.

----------

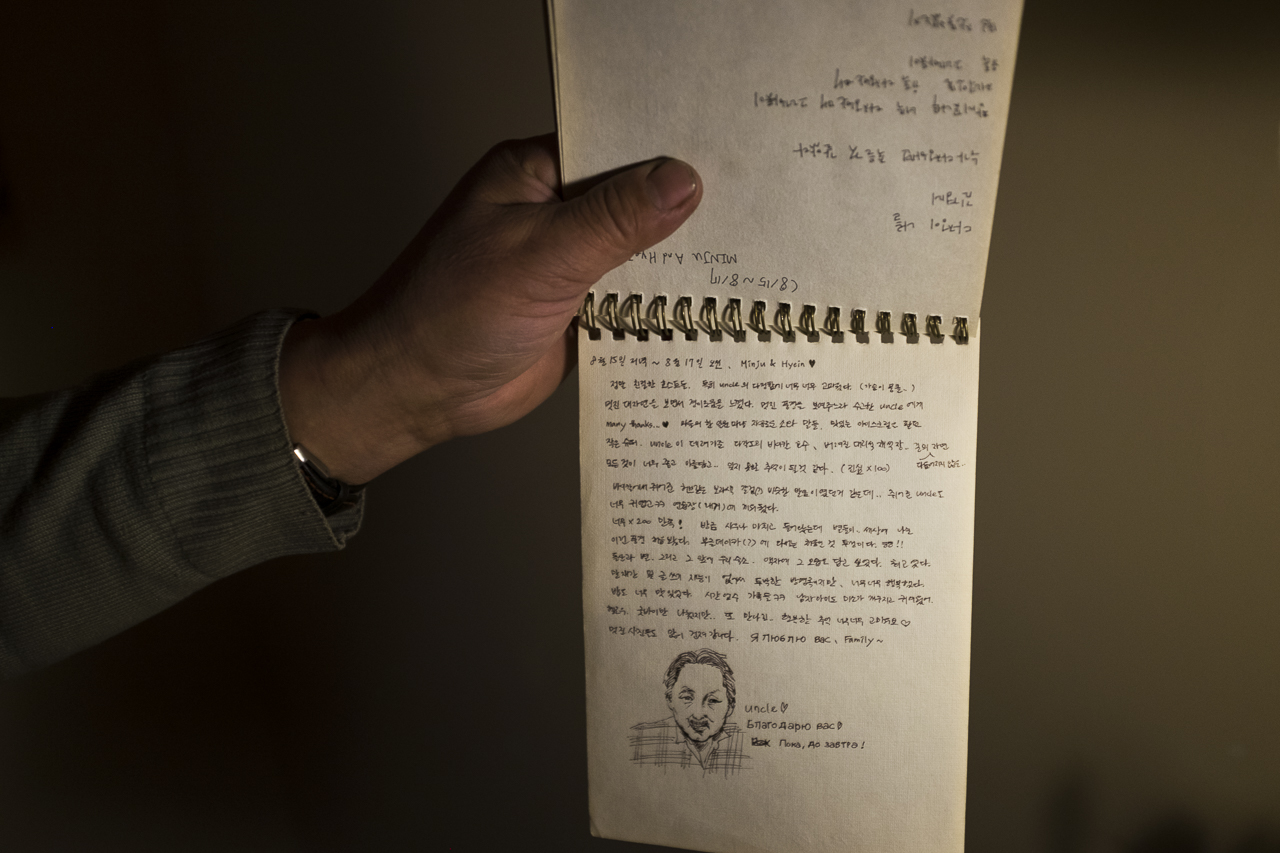

A few important acknowledgements: The music in Embers and Effluents was composed from data about climate change collected by scientists at Irkutsk State University. The music was enhanced in collaboration with Evgeny Masloboev, a highly innovative Irkutsk-based composer and musician. The video also includes footage of underwater life courtesy of the Baikal Museum’s live web-cams and native bird calls captured by Professor B.N. Veprintsev.