The indigenous, traditionally semi-nomadic Buryat people of Eastern Siberia used to live separately from one another until the Soviet Union forced them into collectives where their language and customs were suppressed. Now, in post-Soviet times, many still live side by side with Russians in villages like Bugul’deyka, a tiny hamlet of traditional wooden homes on the Western shore of Lake Baikal. There, Buryat families endeavor simultaneously to preserve important customs and traditions from the past while entering the modern economy.

Thus we came to stay with the Boldakov family in one of the only Airbnb rentals available near Lake Baikal. Run from Italy by multilingual Ilja, a classical Spanish guitarist, the Boldakov family farm, named “Eastories,” welcomes visitors seeking an off-the-beaten-track encounter with the natural beauty of Lake Baikal, the surrounding hills, and the nearby Bugul’deyka River. A visitor might find the path to the outhouse blocked by cows on this working farm, then return to the house to post on social media. But more importantly, the hosts are focused on doing everything in their power to support responsible tourism that preserves the health of the Lake.

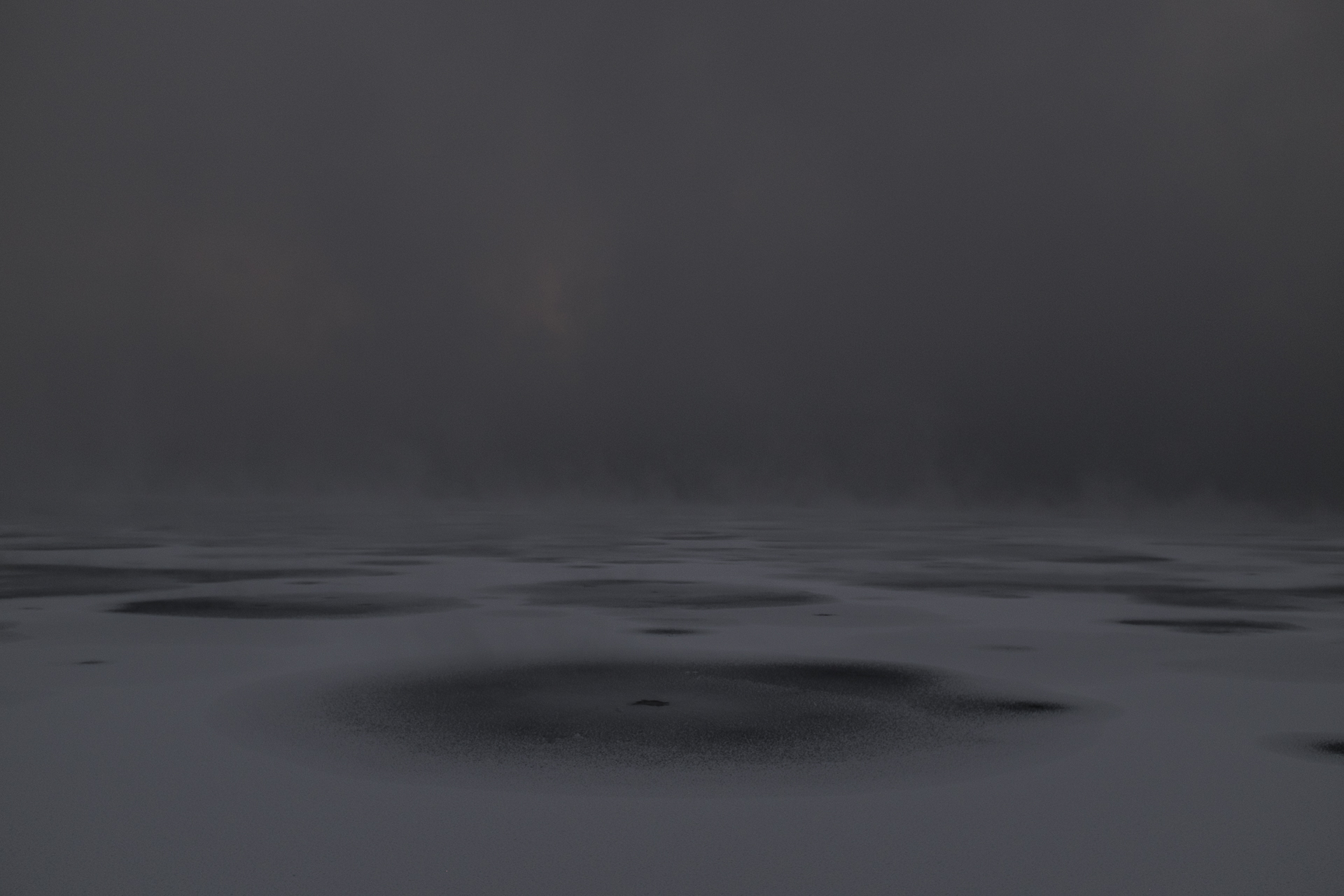

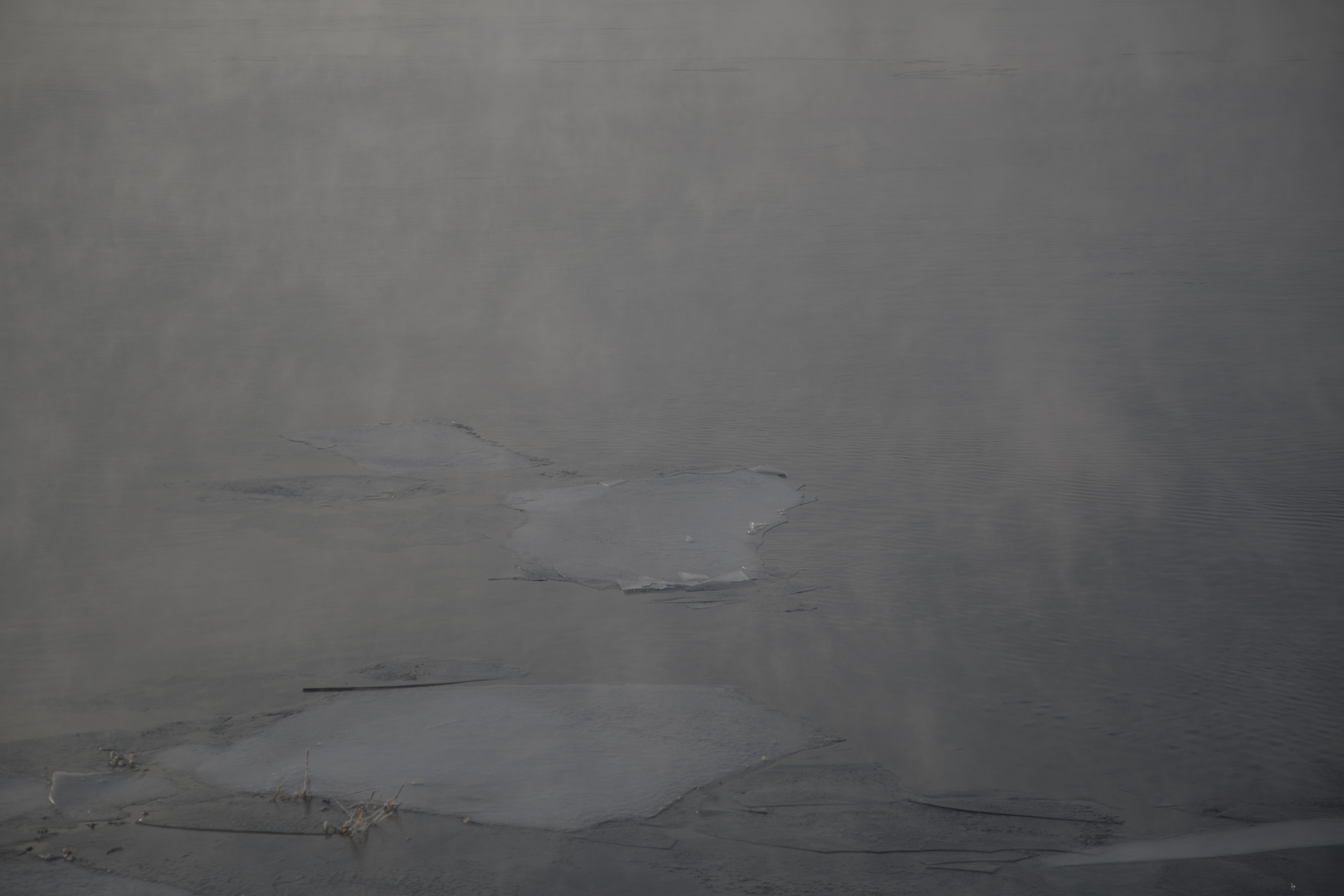

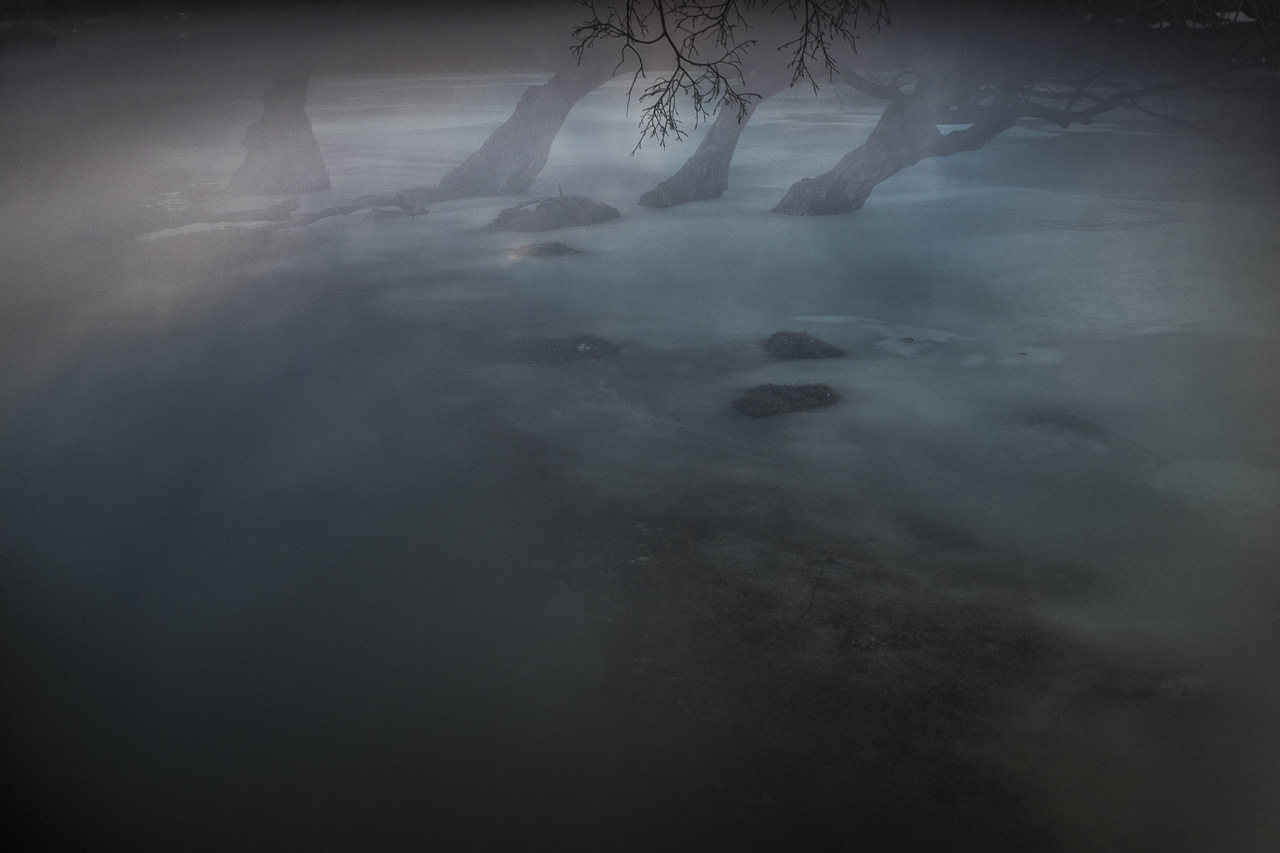

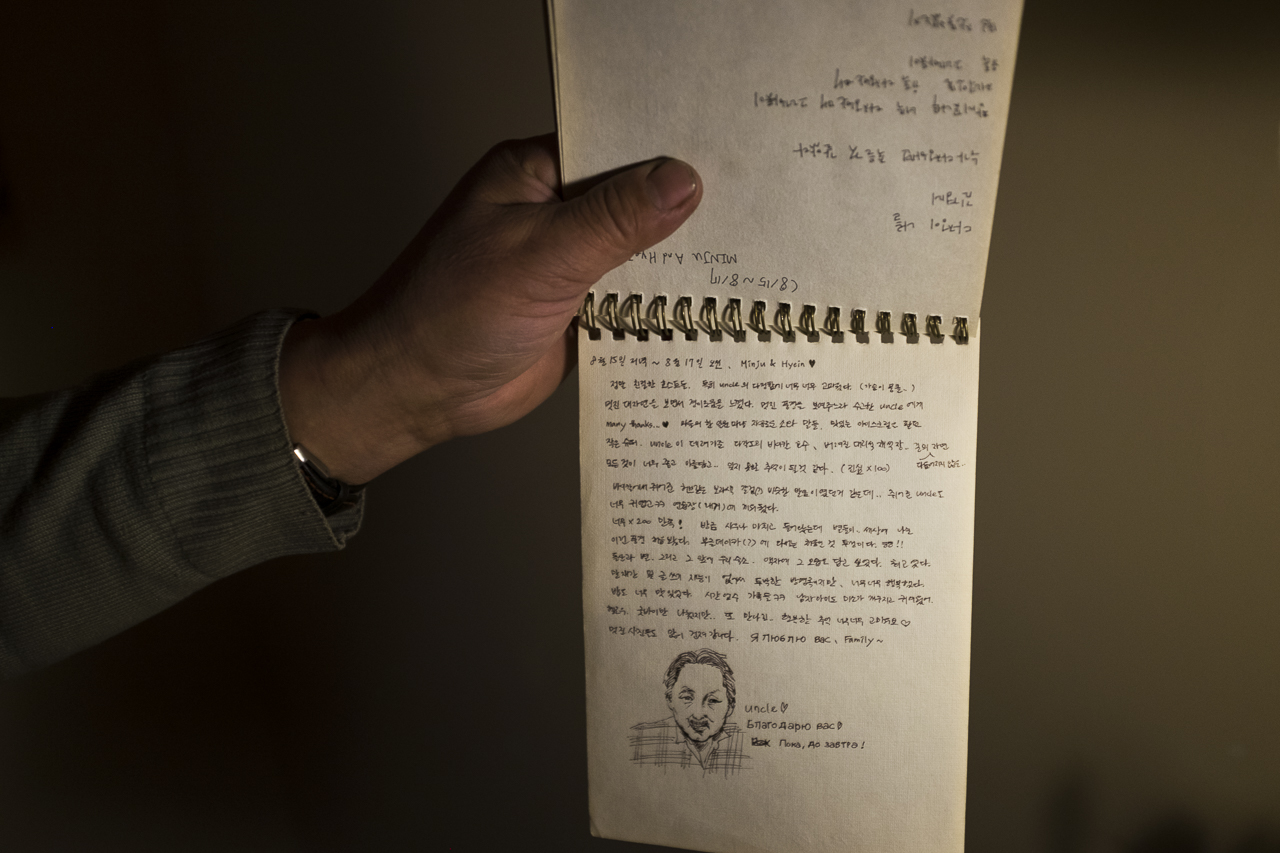

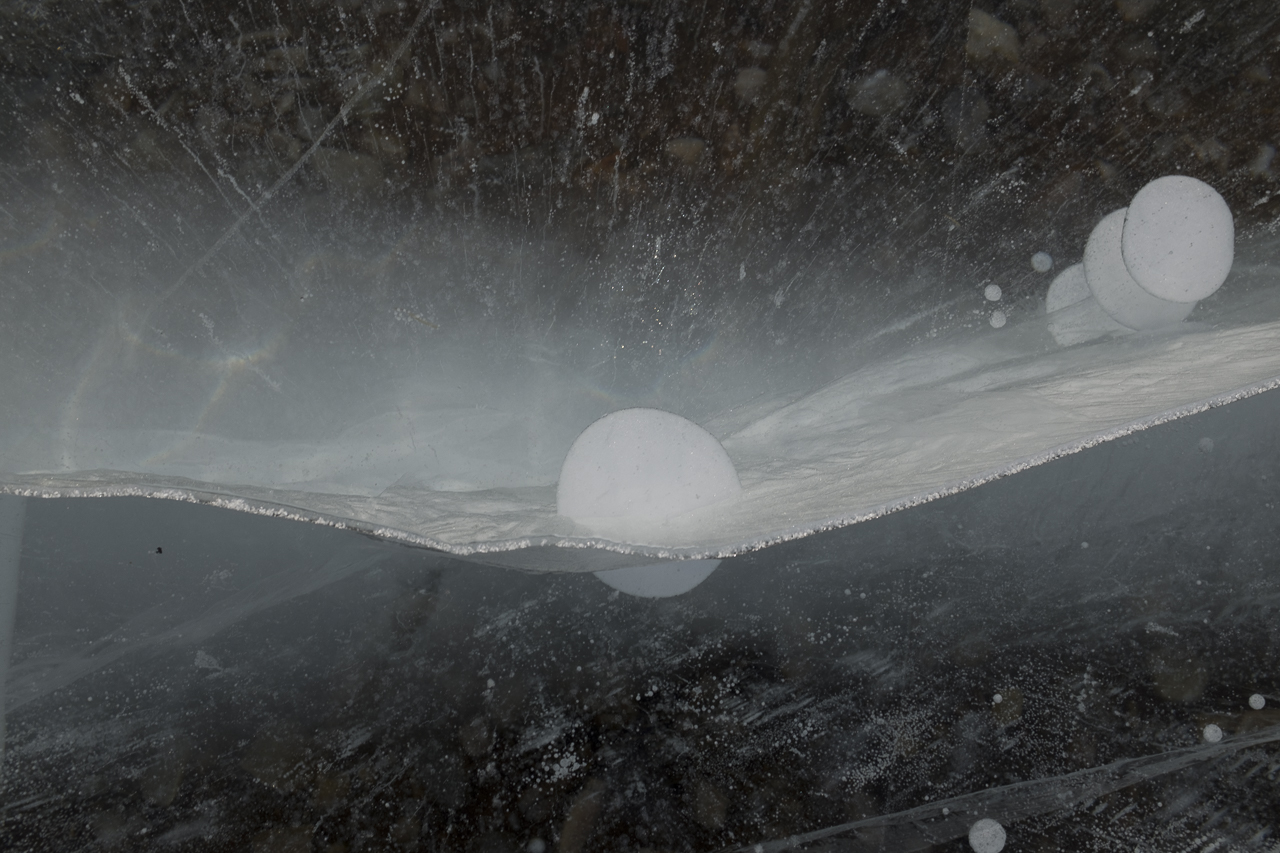

Fingering through the guest book, it was apparent that most visitors come in the summer, with a sprinkling in spring and fall. We came amply prepared for a bitter Siberian winter, wearing as many as six layers on our body, three layers of gloves and mittens, four layers of hats, Arctic boots, and balaclavas to protect our faces. But with temperatures plummeting to -40 Celsius (that’s the same in Fahrenheit!) in the night, and a howling wind relentlessly sweeping through the village and onto the Lake, our preparations were put to the test. We ventured out for at least several hours every day to the Lake, where fog steadily formed over the wind-driven waves and shaped icy sculptures on the banks. We climbed the monochromatic hills and struggled to operate our cameras with brittle, aching fingers until the final day, when we lost our courage and huddled inside, staring through glazed windows at spectacular cloud formations and listening in awe to the wailing blasts of attacking wind.

We survived, but we now know that the best preparations can fall a tiny bit short. Mark had his second experience with “frostnip,” a mild form of frostbite, and Gabriela’s eyes and toes throbbed in the relentless cold. So it was wonderful to return to the Boldakov homestead, where an inviting wooden banya restored full circulation and thawed shivering body parts.

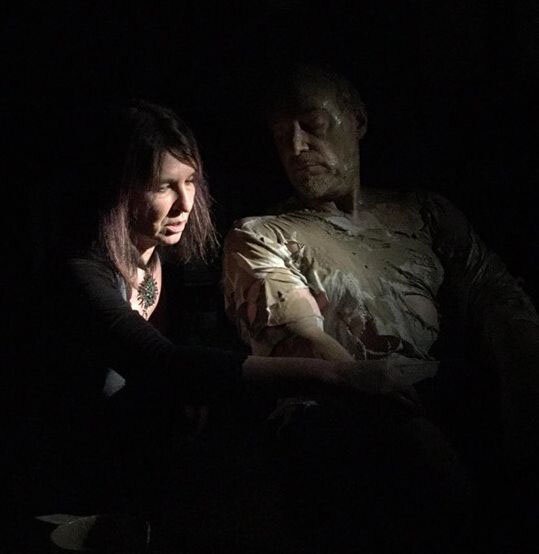

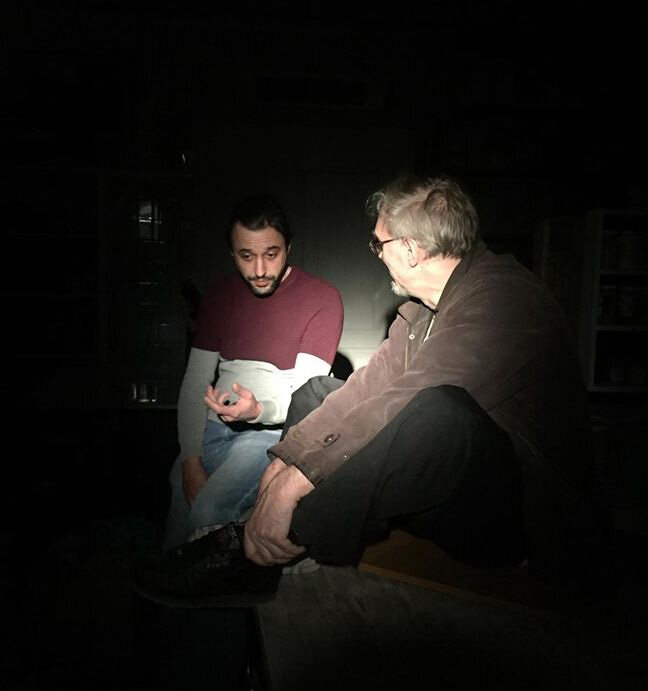

It was also satisfying to sit in front of the traditional Russian “petchka,” or wood-burning stove, where Ilja’s Uncle Volodya, an extremely kind-hearted man with an infectious laugh, shared astonishing tales of the Buryat past and present. In our experience, many Russians began a reminiscence with the phrase, “In Soviet times,” and Volodya was no exception. Like many others, he divided his memories into two categories -- the repressive and cruel actions of Soviet authorities, together with the kinder, gentler economy and humane conditions for workers.

Under the Soviet Union, instruction in the Buryat language was forbidden in schools, and Buryats weren’t educated about their own culture and history. Worse still, their land was appropriated and their lives were threatened if they failed to conform to Soviet ideals. One of Volodya’s grandfathers was taken from his birthplace on Olkhon Island, charged with “pan-Mongolism” and summarily shot. He could have fled in advance, as others did, but he chose to stand his ground and suffer the consequences.

His other grandfather, who lived on the mainland, had his considerable property confiscated and was sent to a prison in the north. The grandfather’s sister, unwilling to tolerate these conditions, fled across the ice of Lake Baikal in the middle of the winter, leaving a one-year old behind because she didn’t dare risk his life in the cold. She escaped to China, then Japan, and she ended up in Australia. But her son who was left behind became a Communist, and when his mother’s letters arrived from abroad, he refused to open them, perhaps because of his beliefs, or perhaps because it could threaten his safety.

Many of these stories came out into the open only recently, because family members were deeply traumatized and didn’t want to talk about them. But recollections of intolerable injustices coexist with positive memories of a time when education was essentially free, there was a very strong forestry and fishing industry, salaries and pensions were high, and living conditions for workers were generous.

Following perestroika, the Buryat language was recognized again, and a revival of Buryat customs is taking place, but Volodya’s generation is considered expendable. Like elsewhere in Russia, the collective farm in Bugul’deyka lies in ruins. There is little investment in the village, jobs are scarce, many houses are crumbling, and electric poles are patched precariously instead of being replaced.

Moreover, Volodya insisted that environmental protections for Lake Baikal and its surroundings were stronger under the Soviet Union than they are now. Officials at the nearby national park aren’t focused on the most important tasks and fail to understand and work with local people, whose respect for the Earth is deeply ingrained in their history.

Despite concern over poor stewardship practices, Volodya has a lot of faith in Baikal’s future. “Baikal is a living, breathing organism,” he asserted. “It is always moving. This is where my ancestors came from, and I’m a little piece of the lake.” While he knows that certain locations are affected by pollution, including chemicals from factories and sewage from increasing tourism, he considers the Lake to be “self-cleaning” and has strong confidence that Bugul’deyka and most of the Lake remains unaffected by these problems.

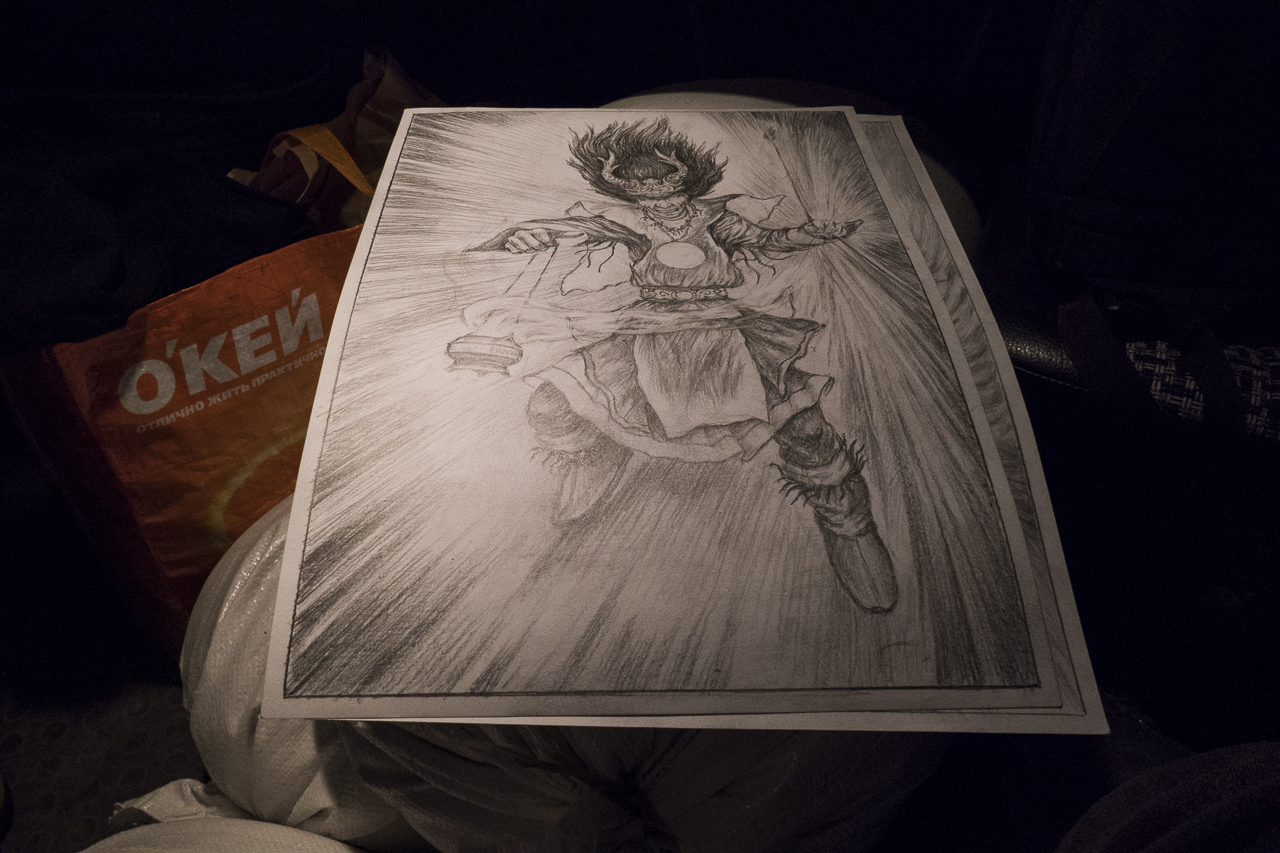

One of Volodya’s biggest worries is that traditional Buryat customs and beliefs are slipping away, including purification and healing techniques such as pressure points that prevent illness. Following a concussion, modern doctors could find no way to treat his continued dizziness, and it was only a female Shaman who restored his health. And at the age of 16, he participated in a ritual in which his uncle killed a ram without spilling any blood, then lay all the ram’s organs on top of his own. After lying underneath, Volodya “became a human being again,” in his own words.

As the fire continued to roar in the background, Volodya performed some simple Buryat rituals. He burned sacred herbs that are reputed to cleanse and purify, walking to the corners of each room to spread their scent. Then he blessed us and our work in Siberia, sharing a shot glass of vodka with us. We each moved our feet in circles three times in opposite directions, then spilled a small amount of vodka onto the hearth, where it hissed and evaporated instantly. Fire is considered an incredible force, helping or destroying depending on how you treat it, and it must be respected. Here, in remote Siberia, we spent our Christmas Eve and Christmas Day huddling around the fire and respecting its warmth and its power.

A Buryat legend says that Bugul’deyka was created when a member of a Buryat clan found a place where grass was wildly abundant and a bucket dipped in the river came out full of fish. Now, life in Bugul’deyka is much more difficult and uncertain, and local people struggle to find the right balance between the ancient and the modern, but faith in Baikal’s future still runs strong. This powerful belief is understandable in a people so deeply connected to the land, who embraced sustainable practices long before the term “ecology” was invented. But if we hope that modern stewards of the Lake and its surroundings will learn from Buryats and find ways to purify and heal the Lake, rather than destroying it in a mad rush to profit, we will all have to play a role.