Gabriela Bulisova & Mark Isaac

It was a long weekend in both the U.S. and the Czech Republic. While the U.S. celebrated its Independence Day in an atmosphere that was decidedly muted and uncertain, the Czech Republic celebrated its greatest religious reformer, Jan Hus, who was martyred in 1415.

The memorial to Jan Hus in Prague’s Old Town Square.

Hus was one of the first leaders of the reform movement in Christianity, long before better-known figures like Martin Luther. After calling for a series of changes in doctrine, Hus was excommunicated and eventually captured and burned at the stake by the church hierarchy. But local believers, called Hussites, defeated five papal crusades and lived true to Hus’s teachings until they came under the control of the Habsburg Monarchy in 1620.

We raise Hus’s memory not to make any point about theology, but to call further attention to the many notable figures who were capable of being powerfully true to their beliefs in this part of the world. Hus was given multiple chances to save his own life by recanting his beliefs. Instead, he is reported to have replied, "I would not for a chapel of gold retreat from the truth!" As flames engulfed him, he could be heard singing Psalms.

The photograph from Jan Palach’s student ID card.

But Jan Hus is not the only Central European Jan who was willing to die for his beliefs. Not far from the memorial to Hus in Prague’s Old Town Square is the site where Jan Palach, a student at Charles University, decided to make the ultimate sacrifice to protest the Soviet invasion and occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1968. Unnerved by the Prague Spring reforms of Alexander Dubcek, who sought “socialism with a human face,” the Soviets rolled tanks into Czechoslovakia and occupied the nation in August of that year. Five months later, distraught over the demoralization of the people of Czechoslovakia, Palach set himself on fire in protest and died several days later in a Prague hospital. His heroic act inspired several others to follow suit, both in Czechoslovakia and in other Warsaw Pact nations. One commentator called it, “arguably the most dramatic suicide of the 20th century.”

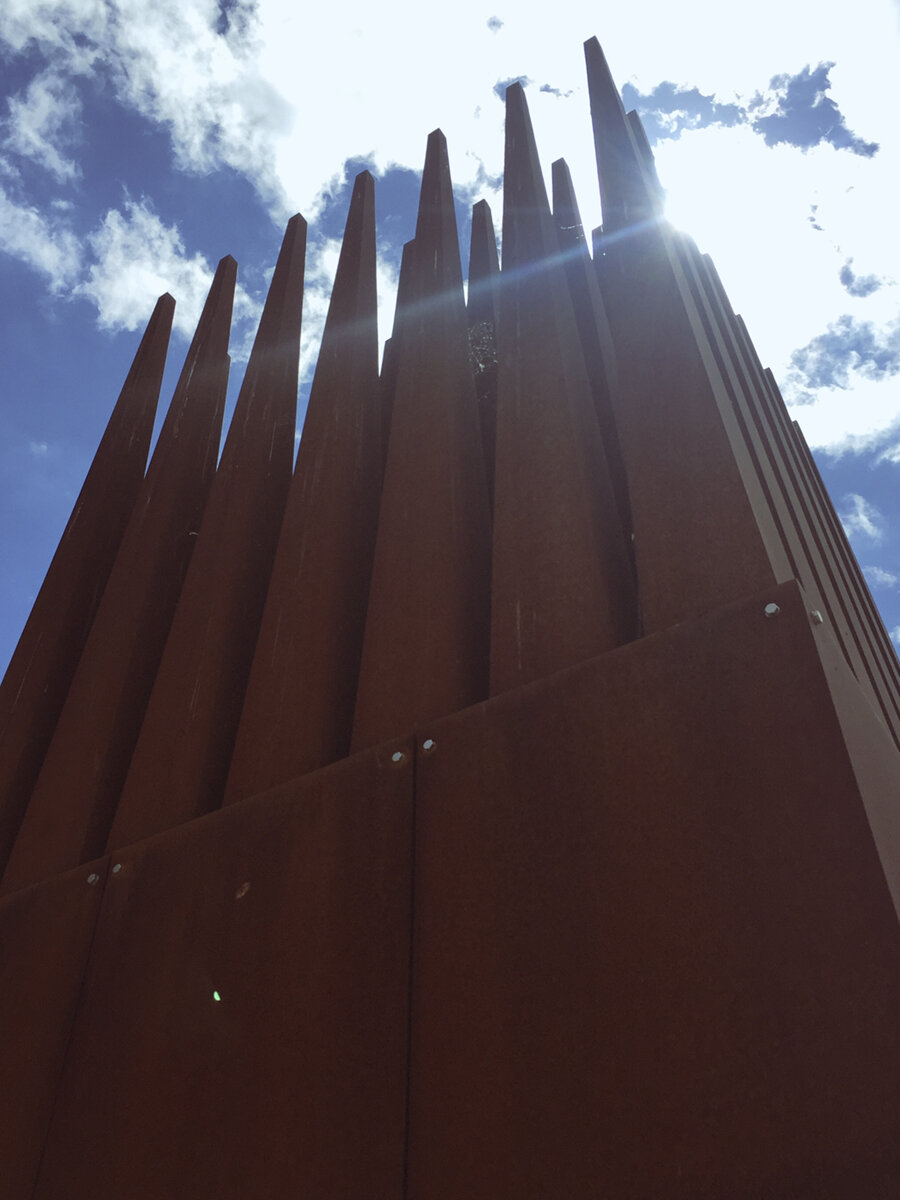

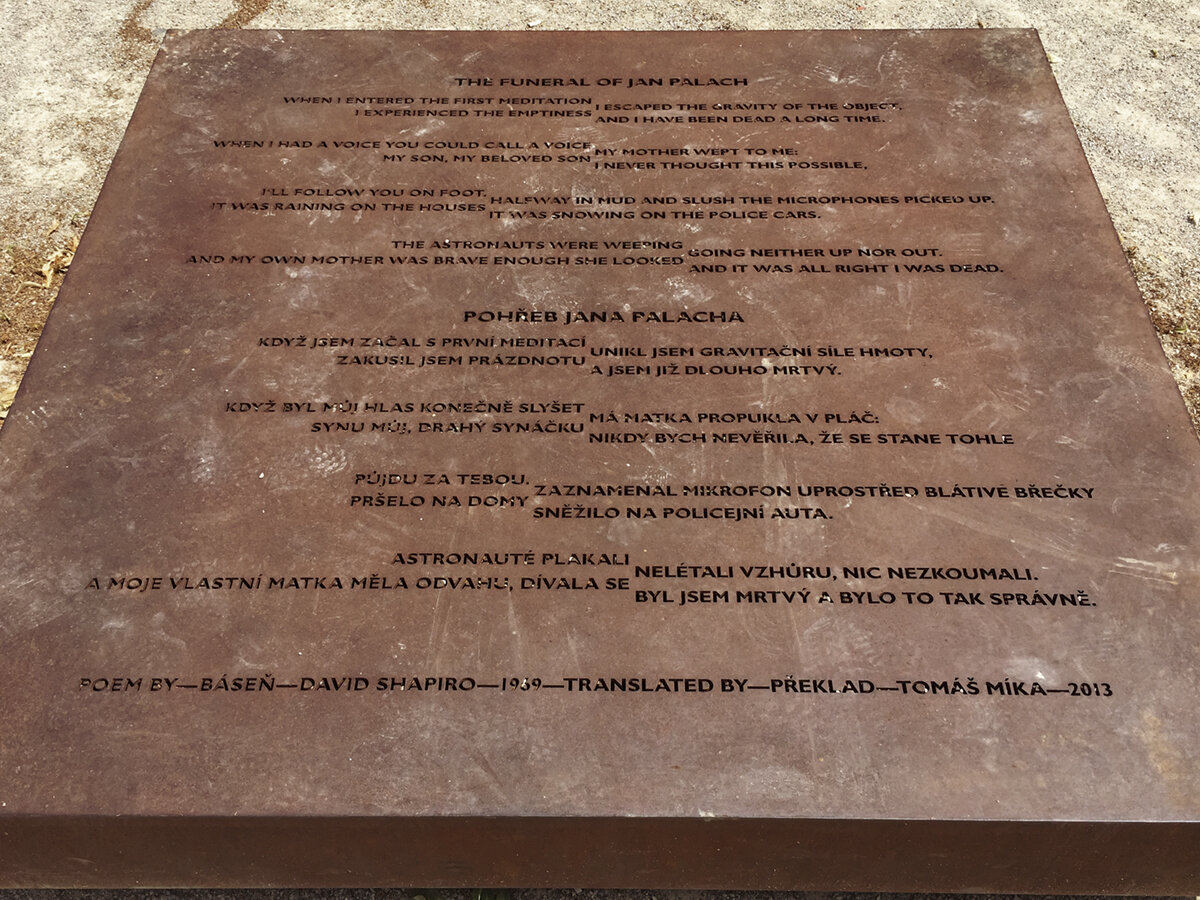

Images from a sculptural memorial to Jan Palach near the Vltava River in Prague.

Jan Kuciak, the Slovak investigative journalist who was shot to death as a result of his exposes of ties between Slovakia’s ruling party and organized crime. Photo: Eva Kubaniova, investigace.cz

And now, a third martyred Jan can be added to the list. Jan Kuciak, an investigative journalist who reported on corrupt ties between officials of the Smer (Direction) political party and organized crime in neighboring Slovakia, was shot to death in his house, along with his fiance, in February 2018. This brazen act sparked outrage throughout the nation and engendered some of the largest protests since the Velvet Revolution. After a lengthy investigation, several people have been tried for the murder, and the notorious businessman Martin Kocner, who was under investigation by Kuciak, is currently on trial for ordering his murder. Kuciak’s assassination led to a series of dramatic changes in Slovakia, including: the resignation of former Prime Minister Robert Fico; the election of the first female, progressive President, the remarkable Zuzana Caputova, who is committed to a reform agenda; and the downfall of the Smer Party in the most recent parliamentary election.

The fact that all three of these men are named Jan has not been lost on observers, and graffiti has appeared on the streets listing all their names together. But of course it is not a requirement to be named Jan to stand up for one’s beliefs, and it is certainly not a requirement to be male. A few days ago, we reported on the moving tribute that marked the 70th anniversary of the execution of Milada Horakova by the Communist Party in Czechoslovakia. Please read that post also for another story of superhuman Central European courage.

A memorial to Jan Kuciak and his fiance, Martina Kušnírová, in the Square of the Slovak National Uprising in Bratislava, Slovakia.

Now, on the occasion of Jan Hus Day, we venerate not only the three Jans, but the importance of free expression and conscience for all people. We know that in many places around the world, democracy is in decline, freedom of thought is evaporating, and journalists are subject to harassment and violence. One of those countries, sadly, is the United States, and it’s time to face up to that fact very directly. Now is a compelling moment to be inspired by those who sacrificed to defend these freedoms, and search for the right way to make our own, purposeful contributions.

When it comes to defending basic human rights and dignity, after all, it’s “Jan for all; all for Jan.”