Gabriela Bulisova & Mark Isaac

Pacific swifts that spend the summer in Siberia migrated in August to their winter home in Australia and Indonesia.

The swifts lived in the roof above our apartment. They often woke us in a cacophony of sound at about 6:00 a.m. They swooped and cavorted and dive-bombed in the treetops just outside our windows. But the Siberian summer is warm, exquisite, and brief, like a sun-ripened fruit. And its time had already passed. As temperatures also swooped lower, we woke to find that the birds had vanished...already traveling an exceptional distance to winter in Australia or Indonesia. And it was time for us to take flight also, leaving behind a very unexpected and welcoming homeland in the Far East (see Cyberian Dispatch 19).

As we left, the complications of climate change were at play around the globe. Unprecedented wildfires in Brazil and the Arctic captured headlines around the world and were a topic among heads of state. A major hurricane, rated among the most powerful in the North Atlantic of all time, decimated part of the Bahamas and raked the coastal United States and Canada. Alaska’s sea ice melted completely for the first time in history. Iceland’s Prime Minister officiated at a memorial for a lost glacier.

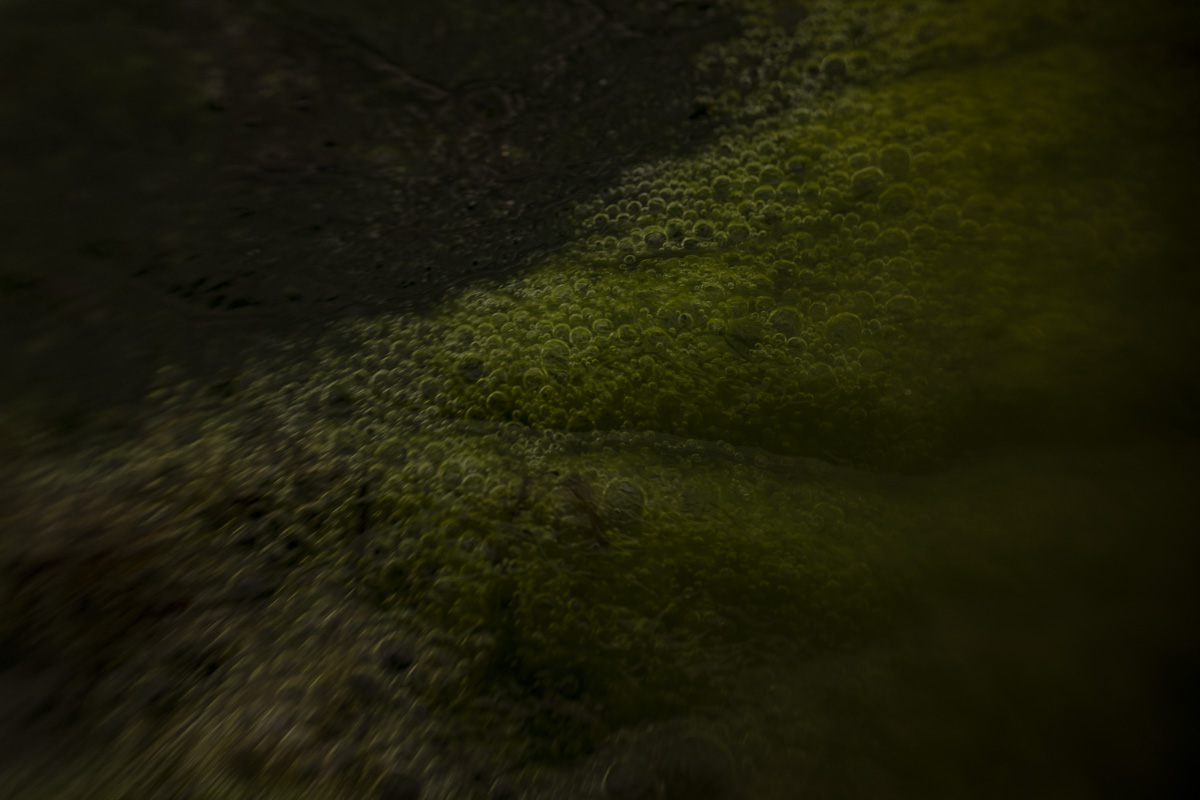

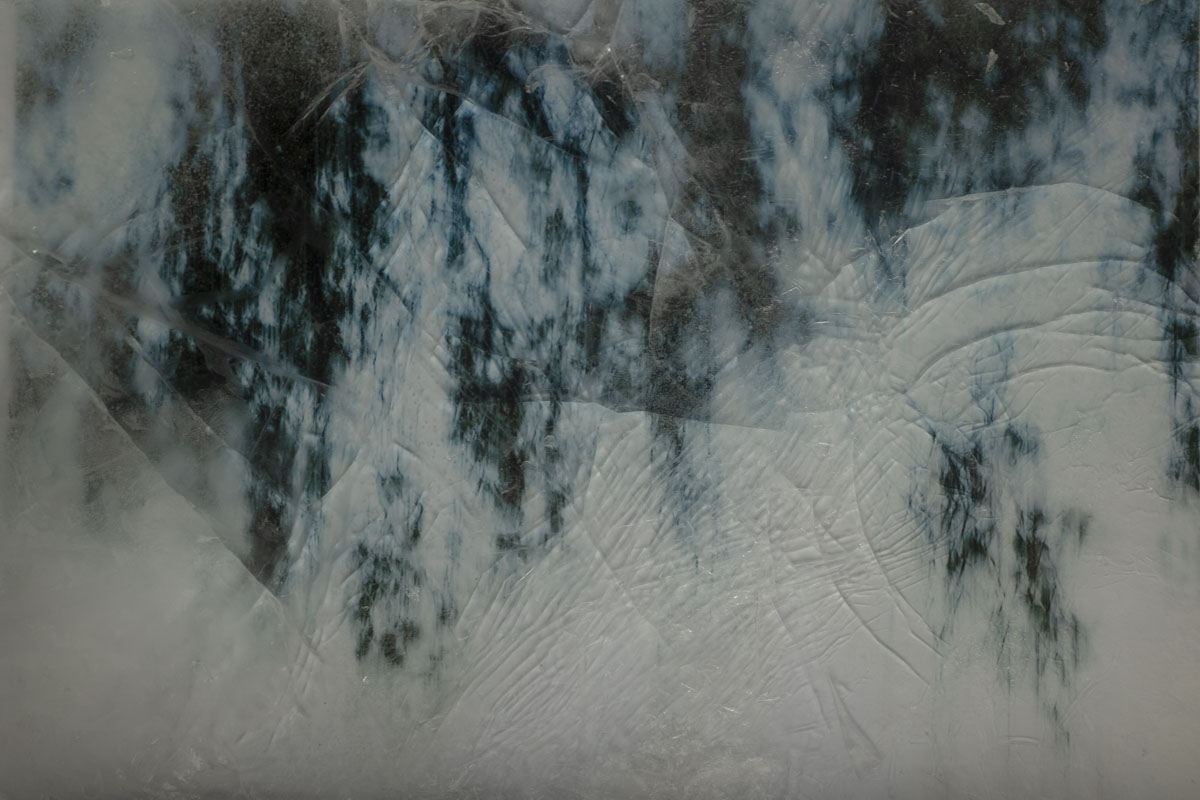

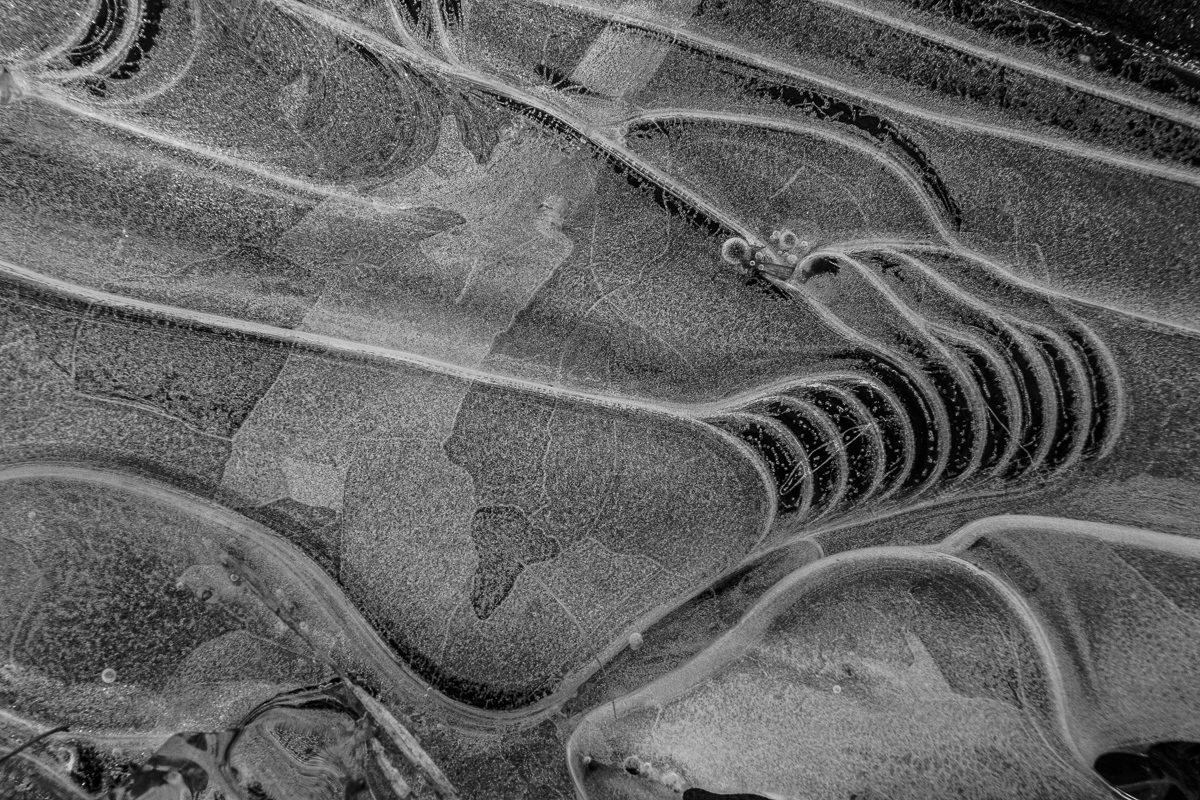

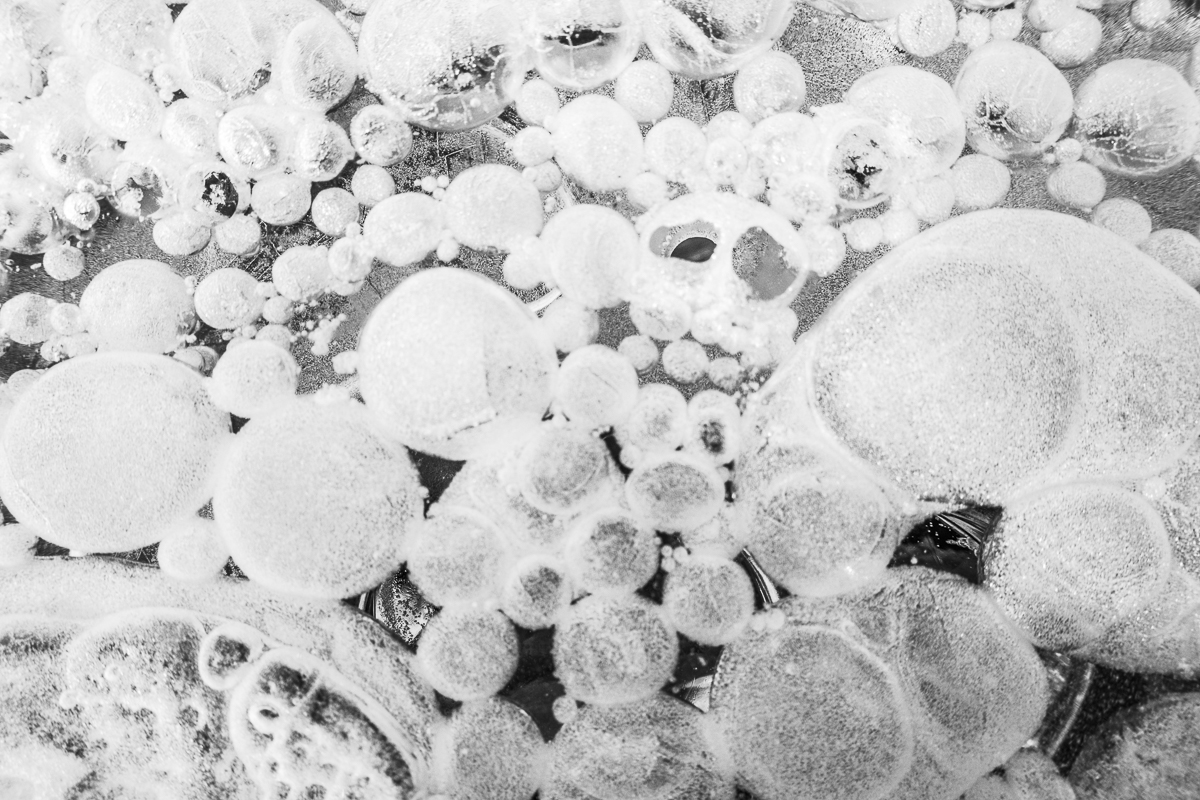

Unfortunately, Siberia and Lake Baikal are in the vanguard of these changes, with temperatures increasing two times faster than other parts of the globe. In our final weeks, multiple challenges punctuated the news, emphasizing Siberia’s leading role in climate change. Wildfires in Siberia, accelerated by high temperatures and extremely dry conditions, consumed an area larger than the nation of Belgium, sometimes sending thick blankets of smoke into Irkutsk and raising air quality alerts to the urgent level. Also, areas north of Irkutsk -- especially Tulun -- suffered severe floods in which dozens lost their lives, and Greenpeace Russia attributed the catastrophe to climate change. Scientists once again reported that Baikal’s precious small organisms are vulnerable to rising temperatures and will suffer, disrupting the Lake’s entire ecosystem, if water temperatures continue to rise.

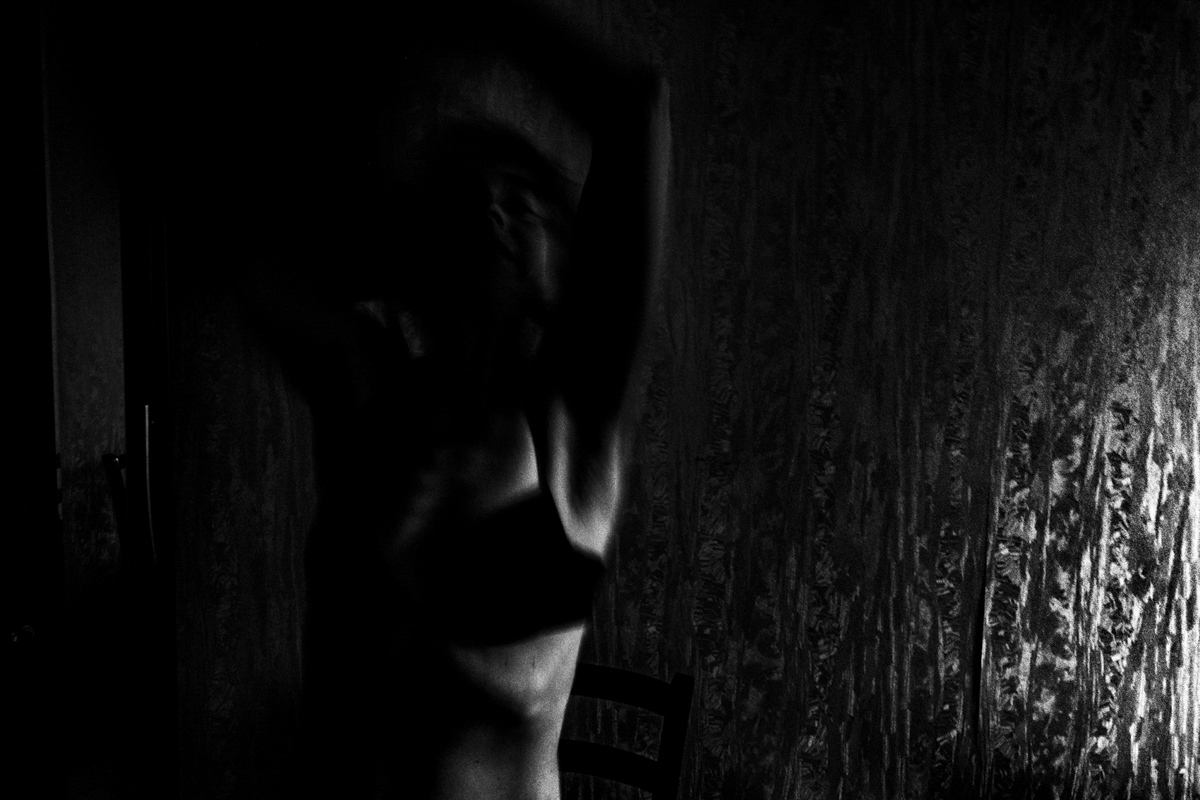

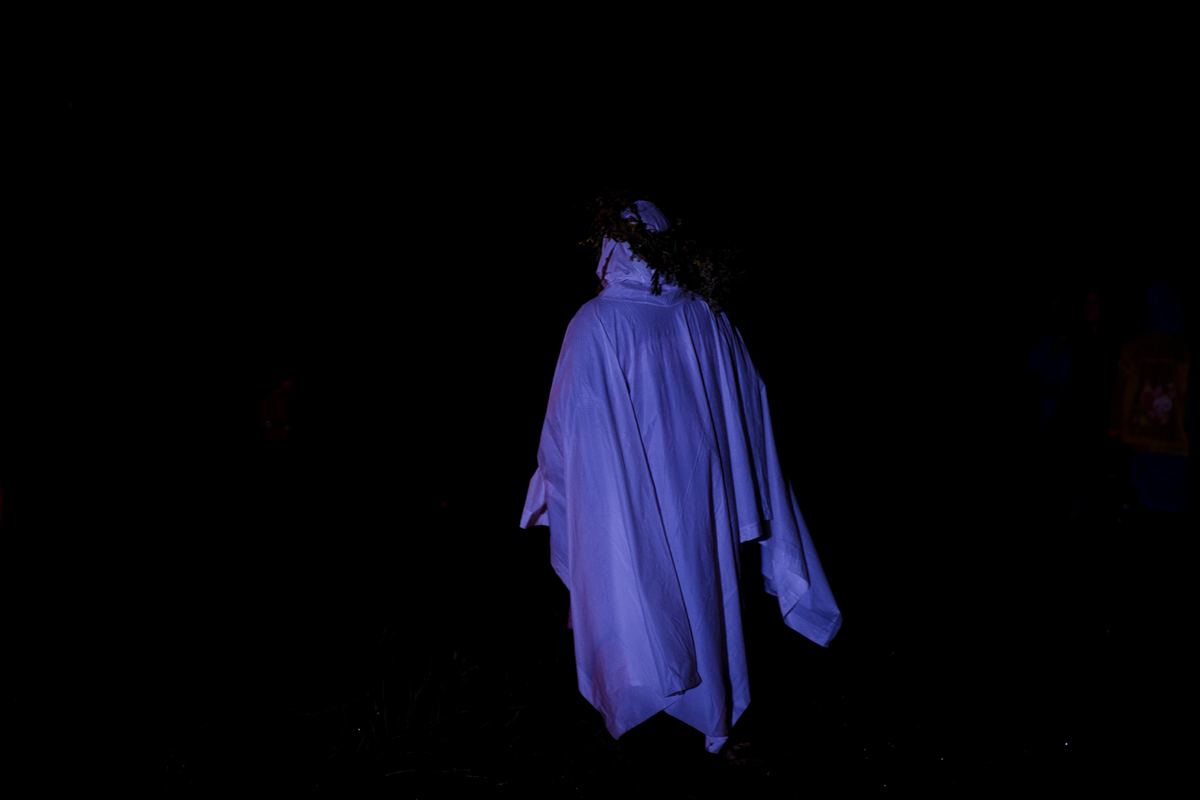

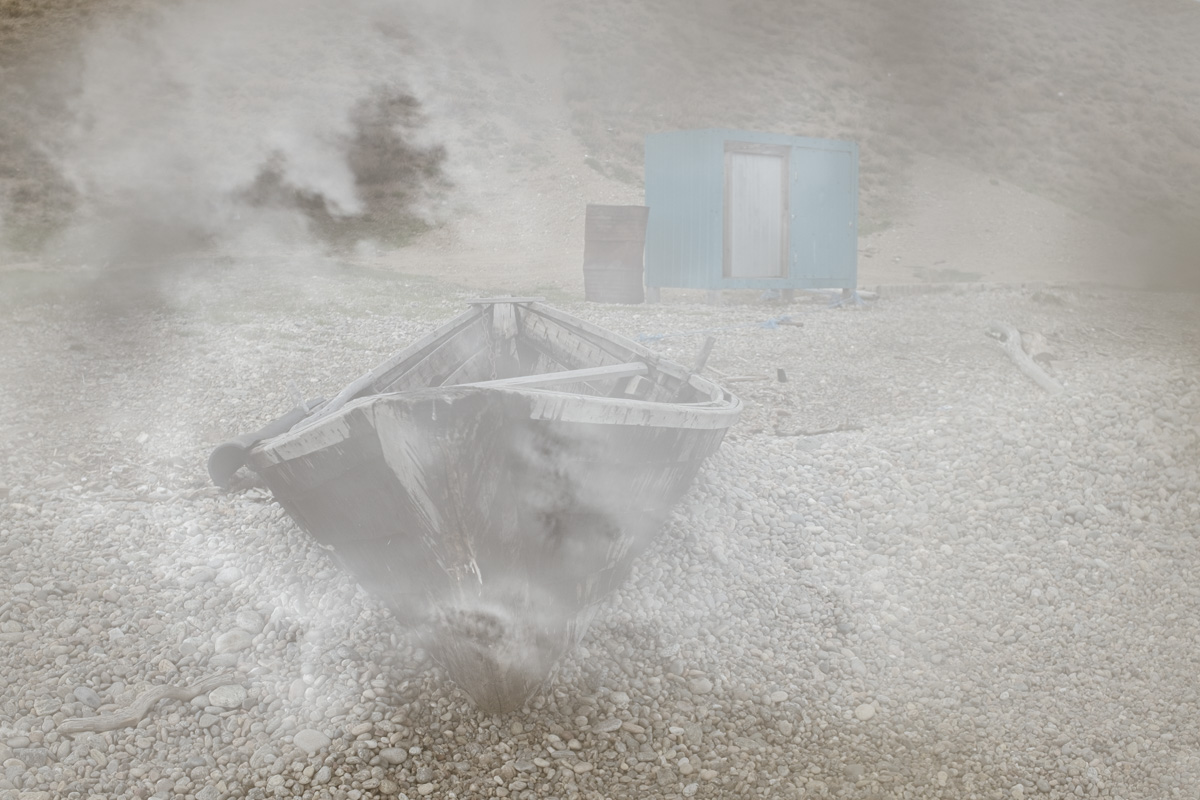

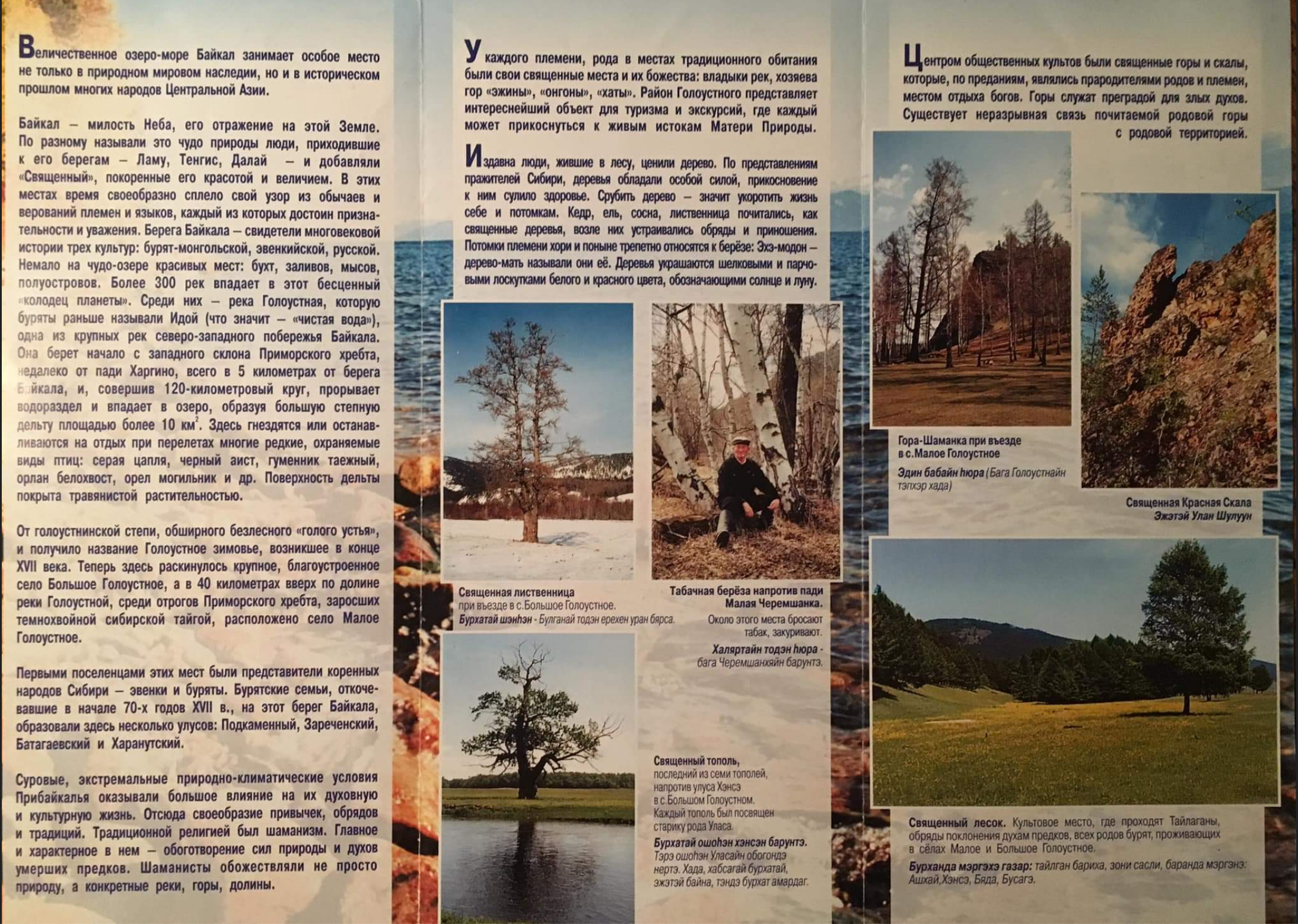

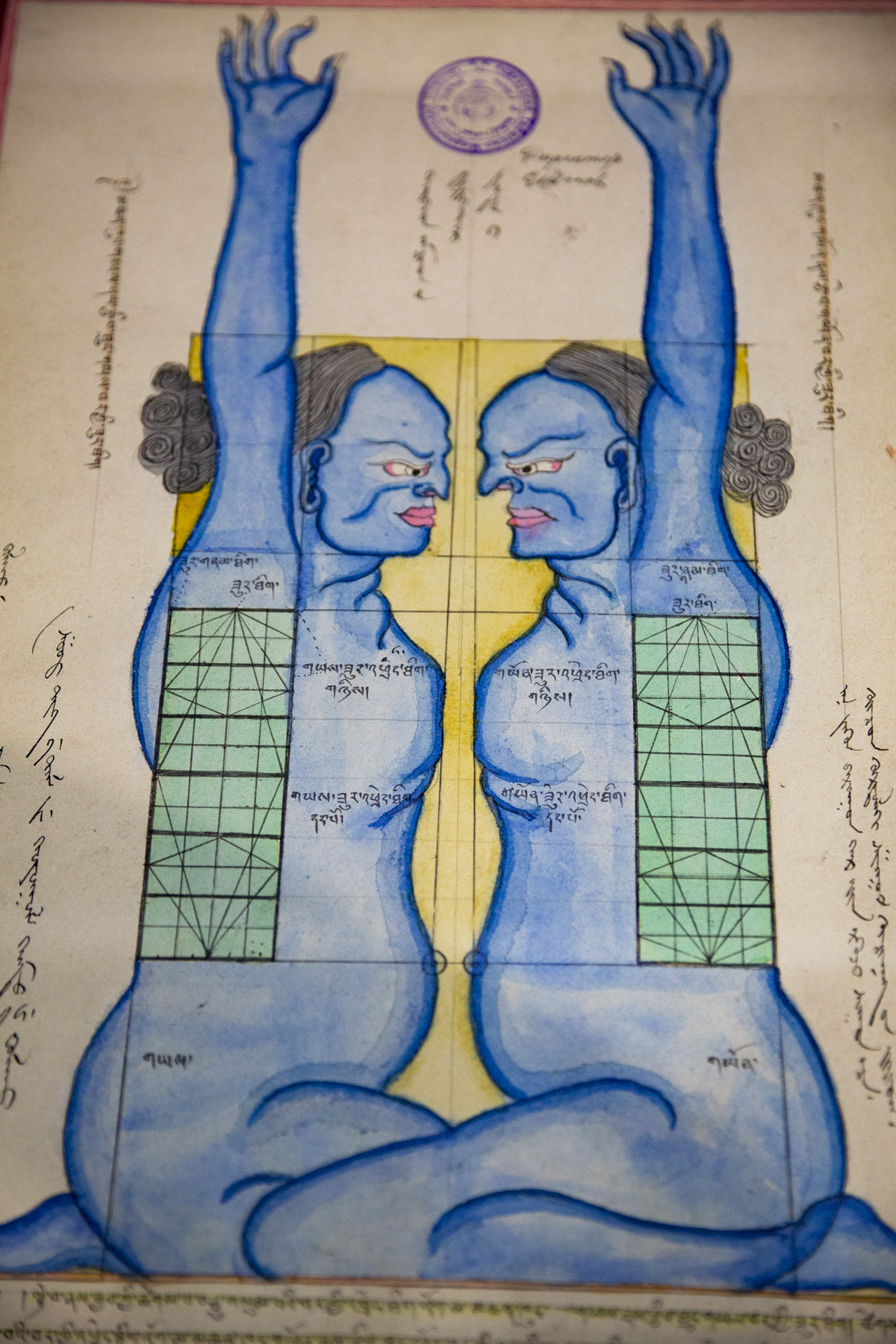

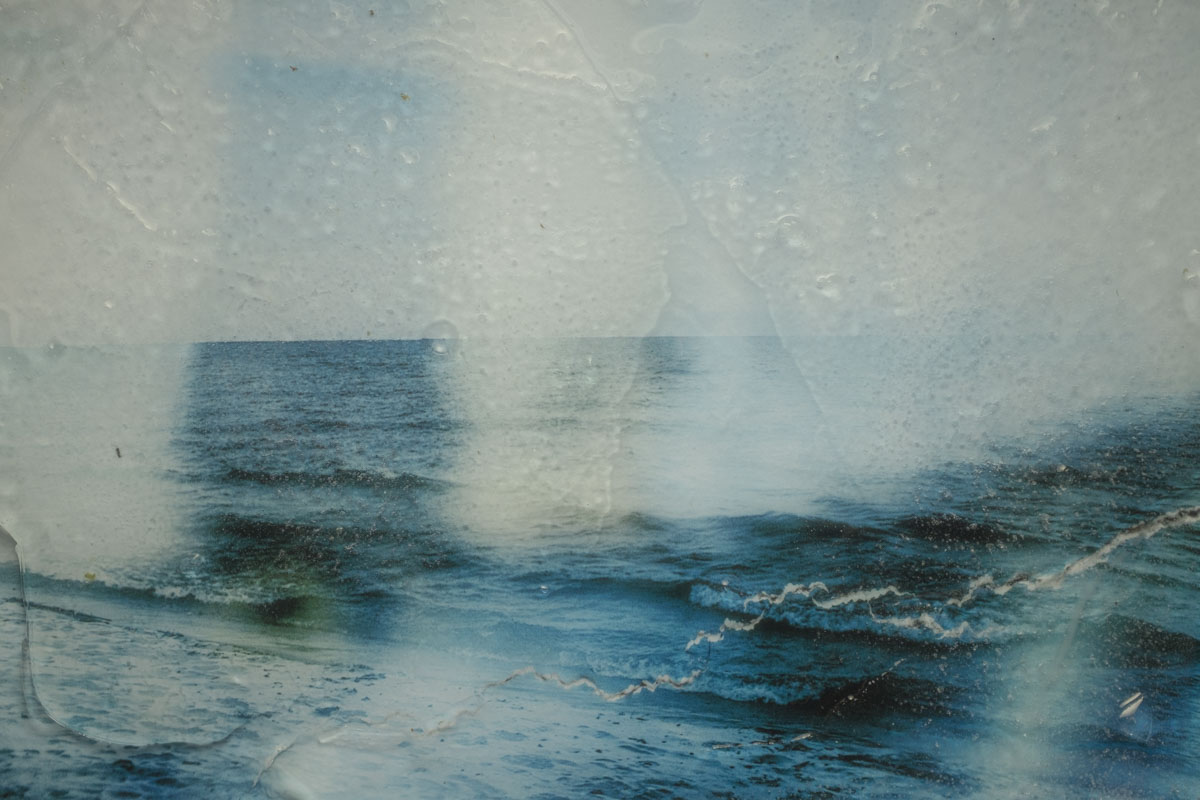

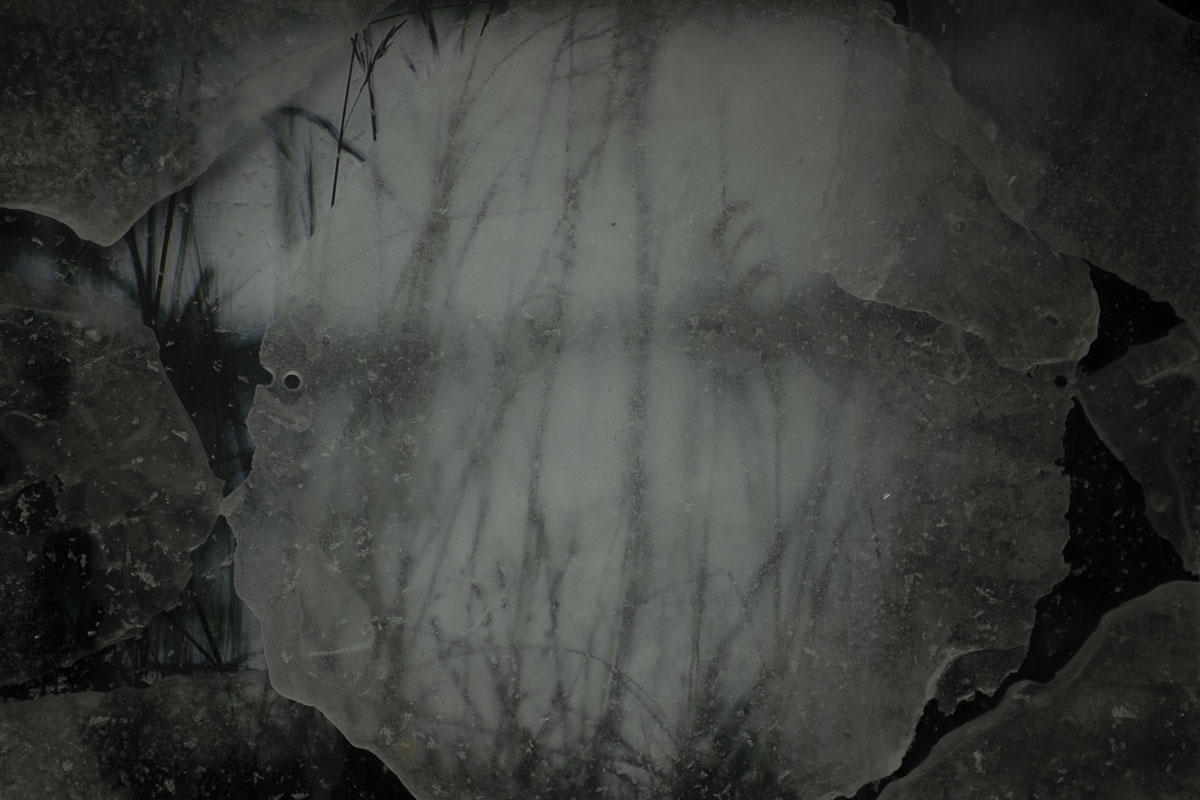

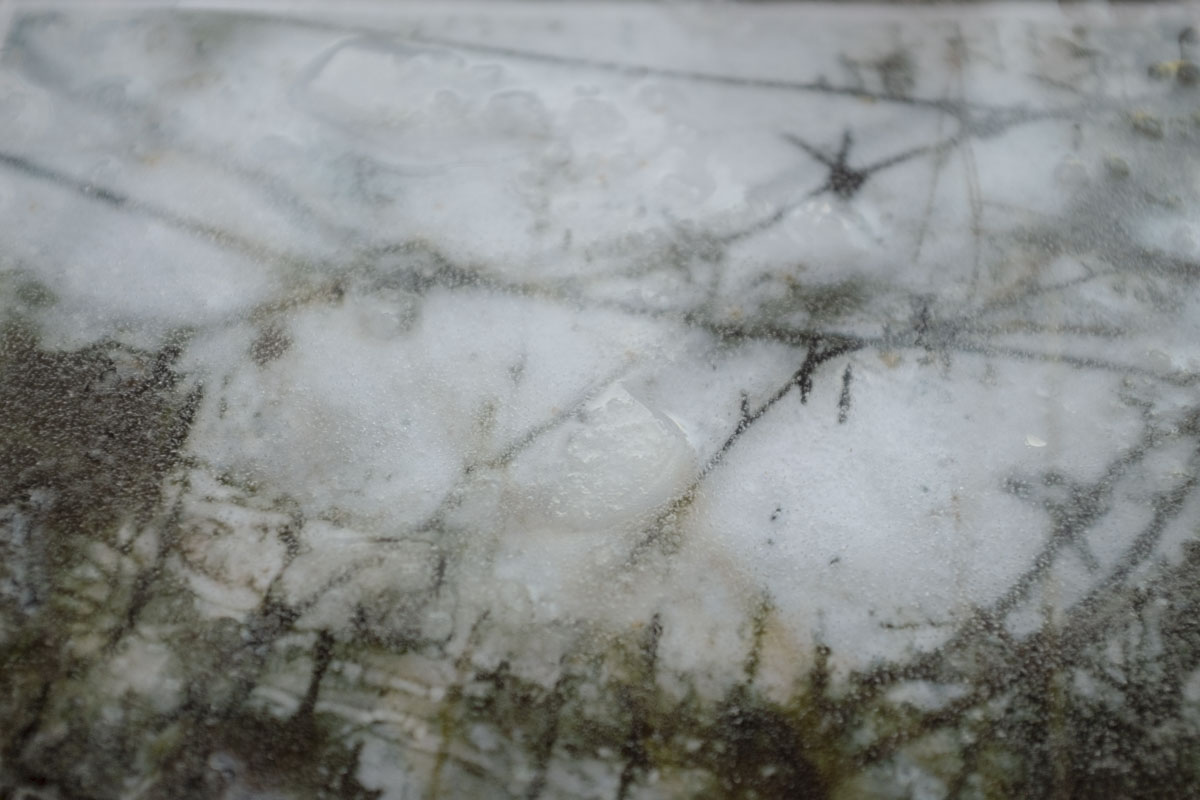

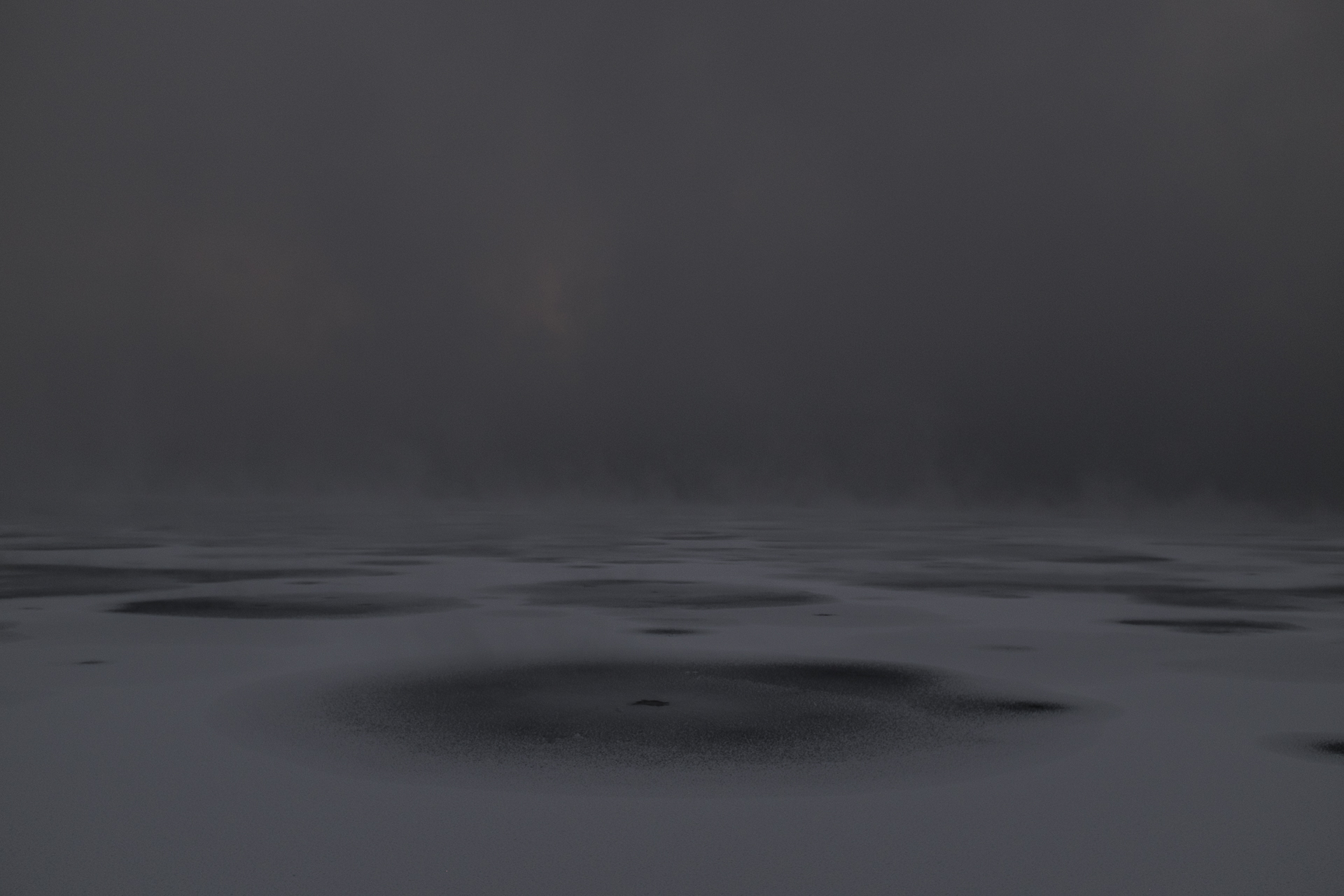

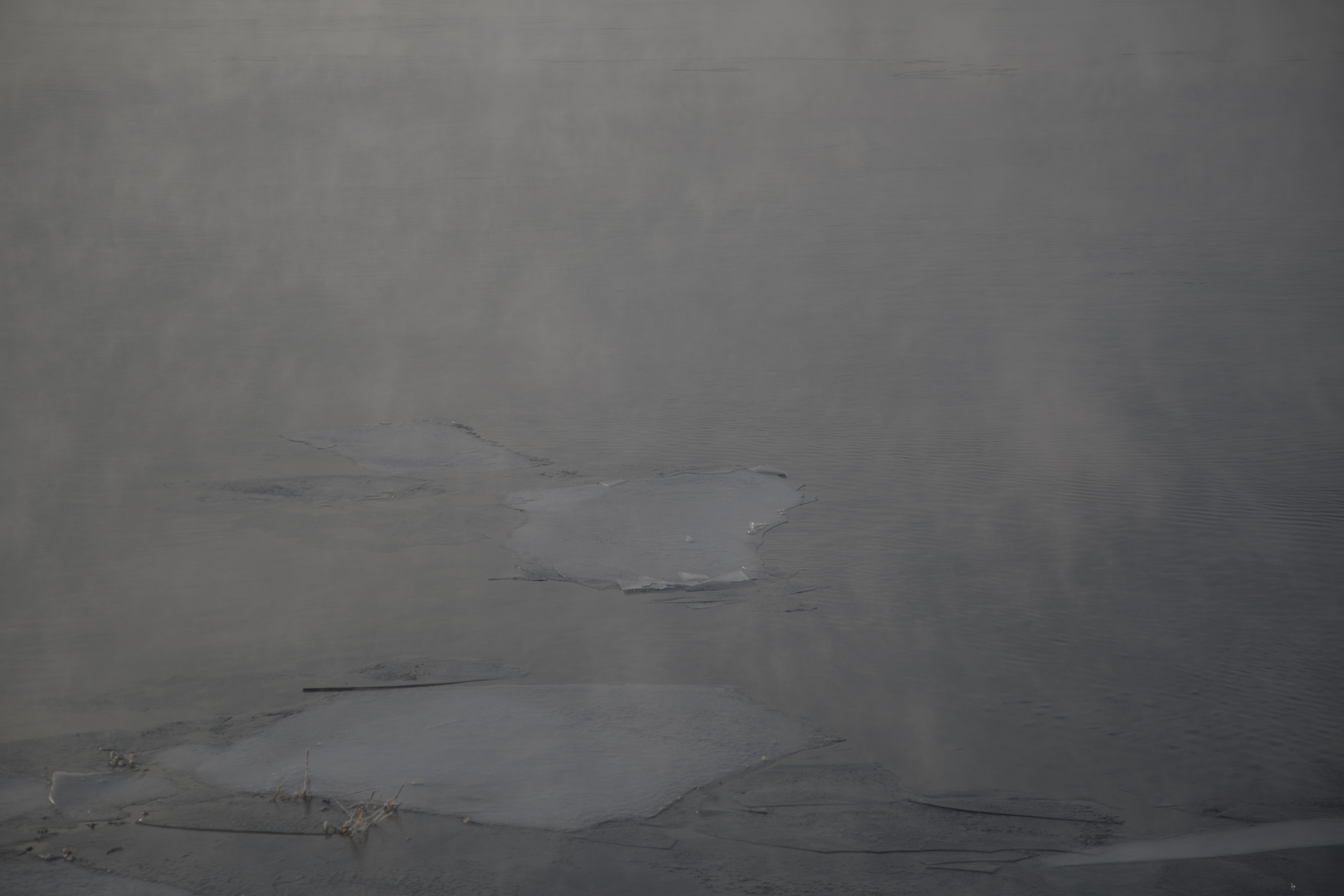

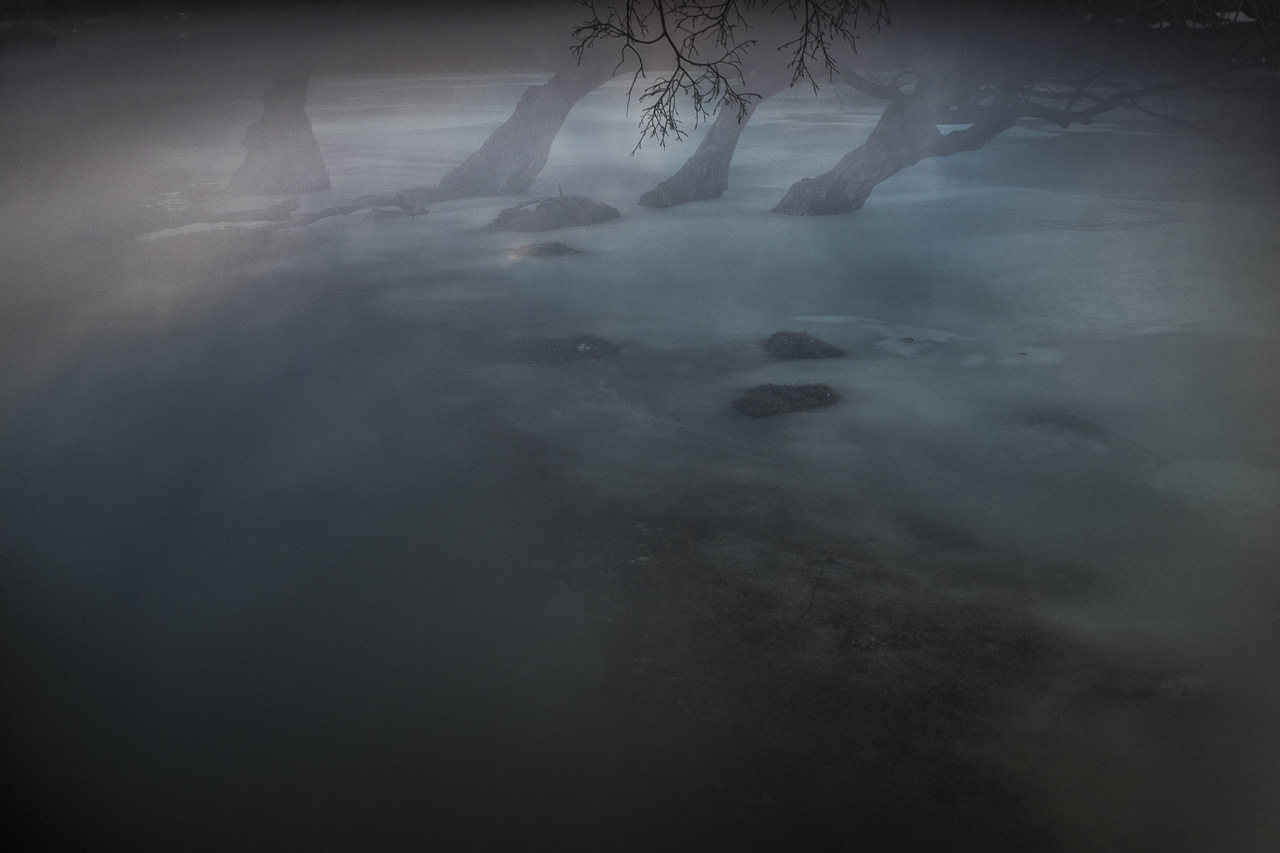

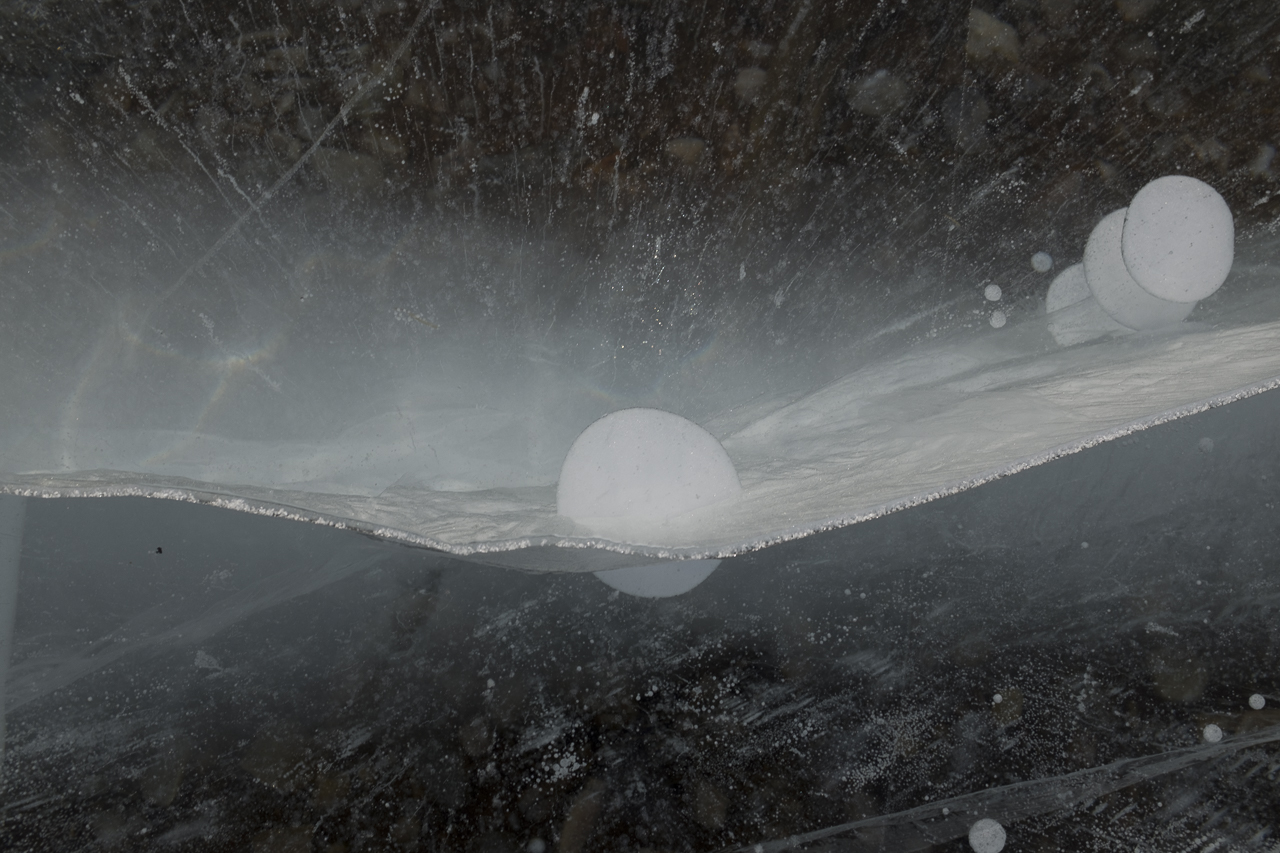

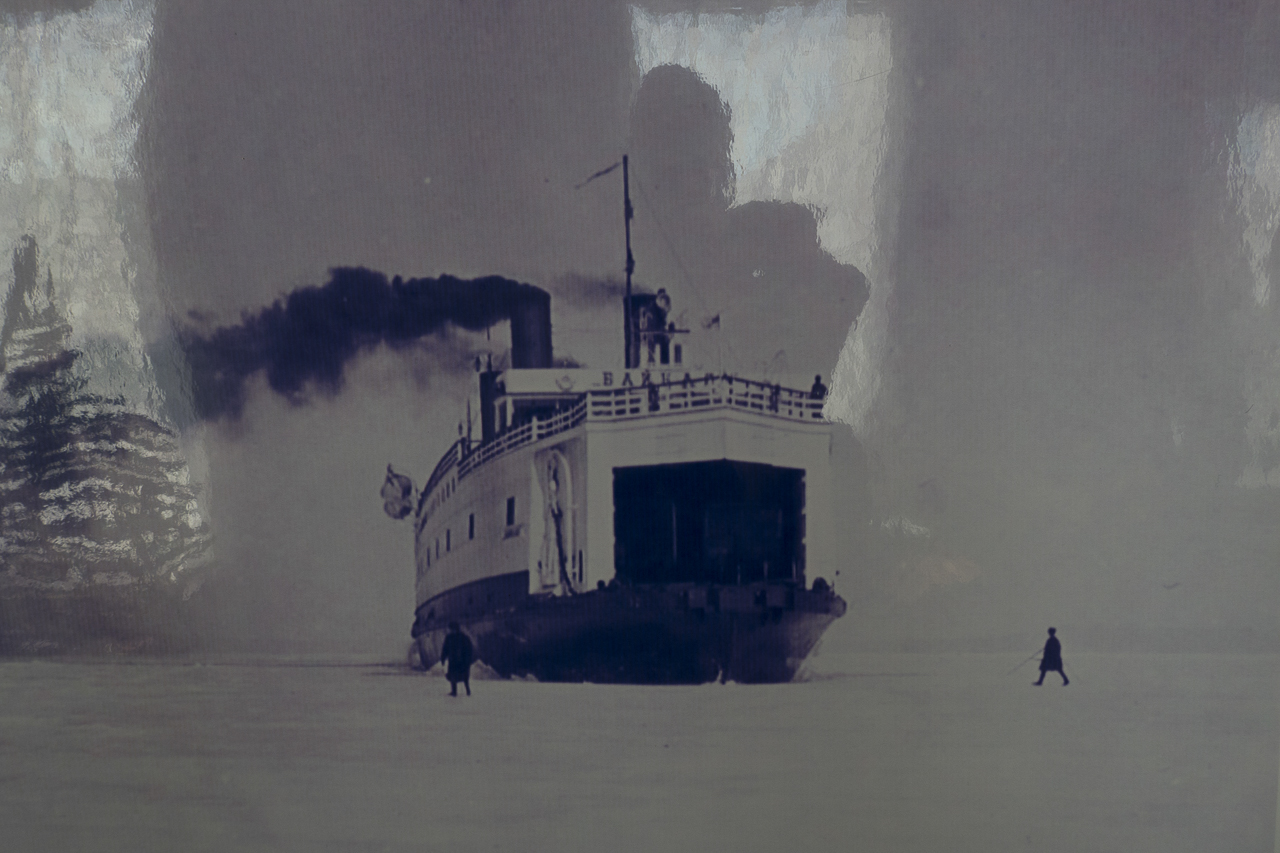

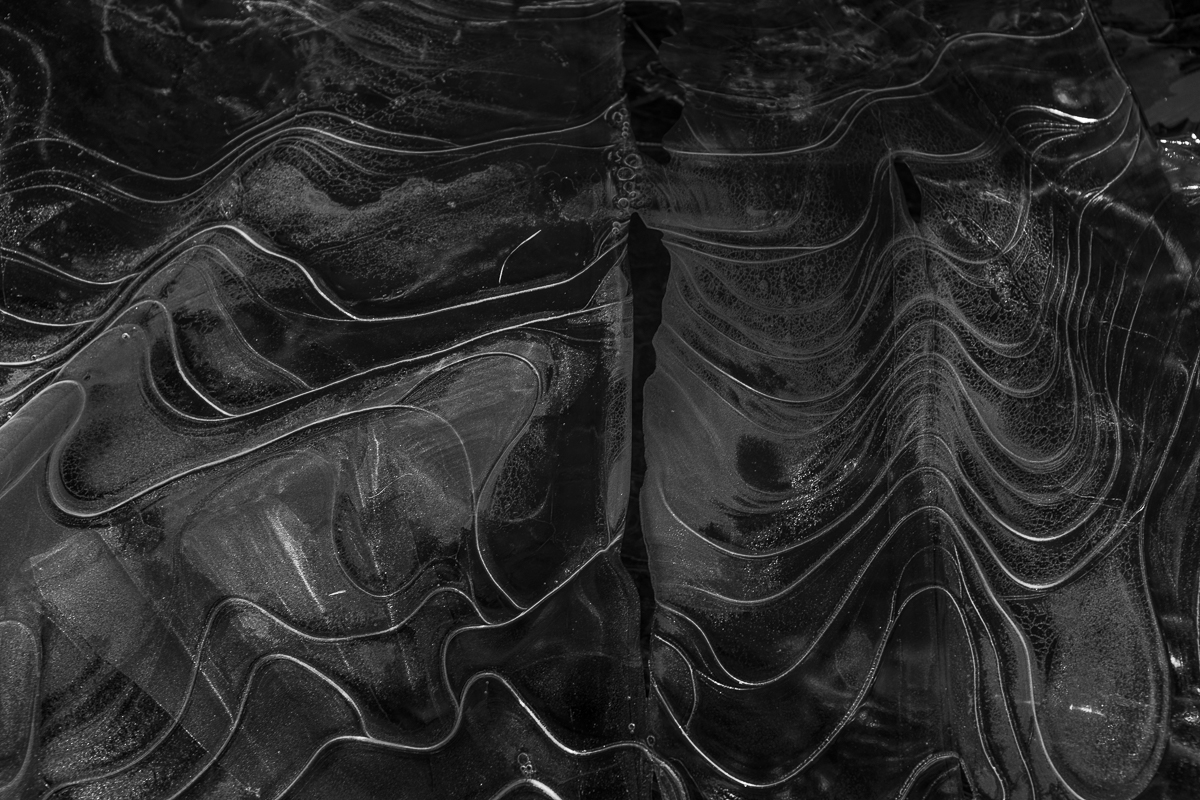

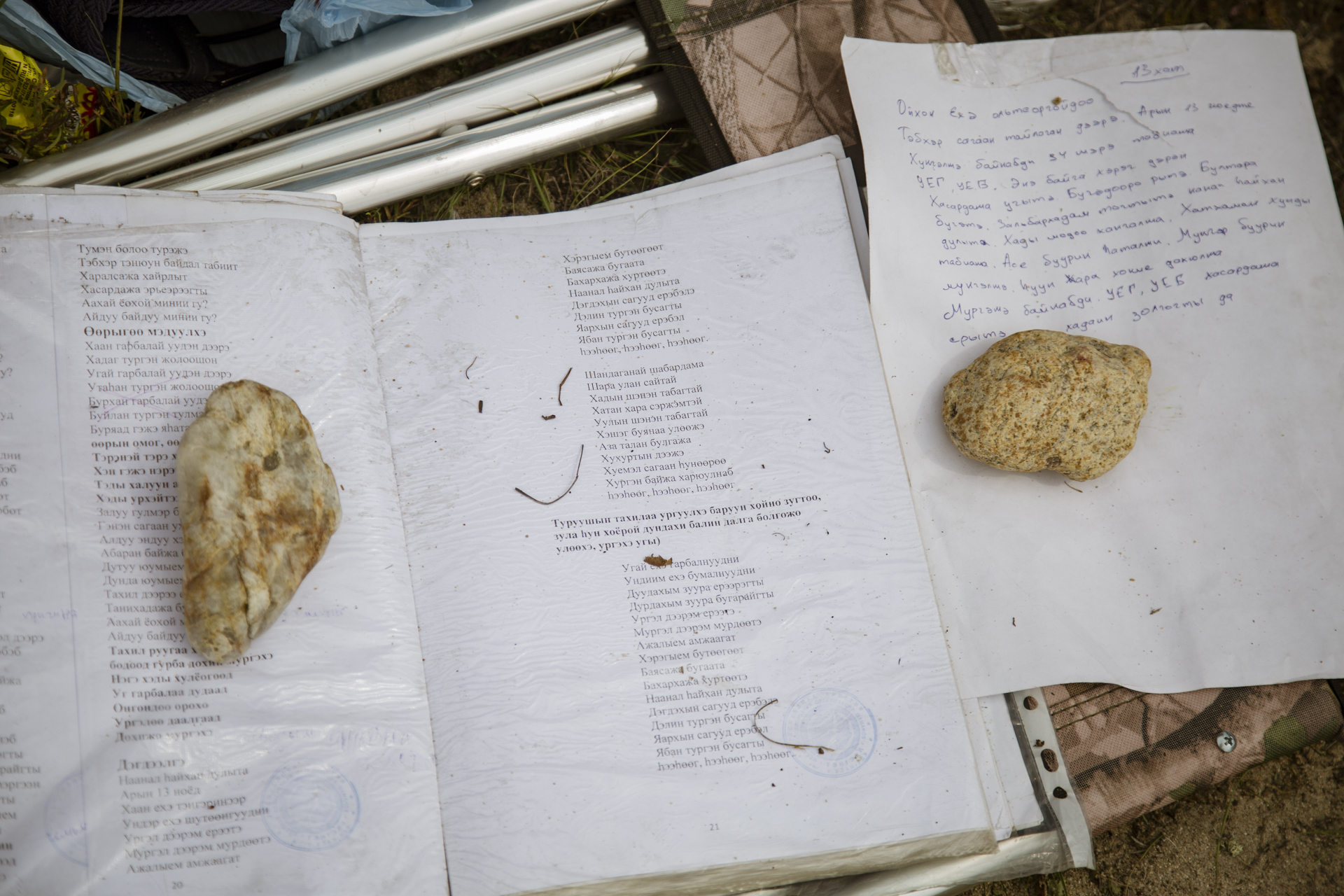

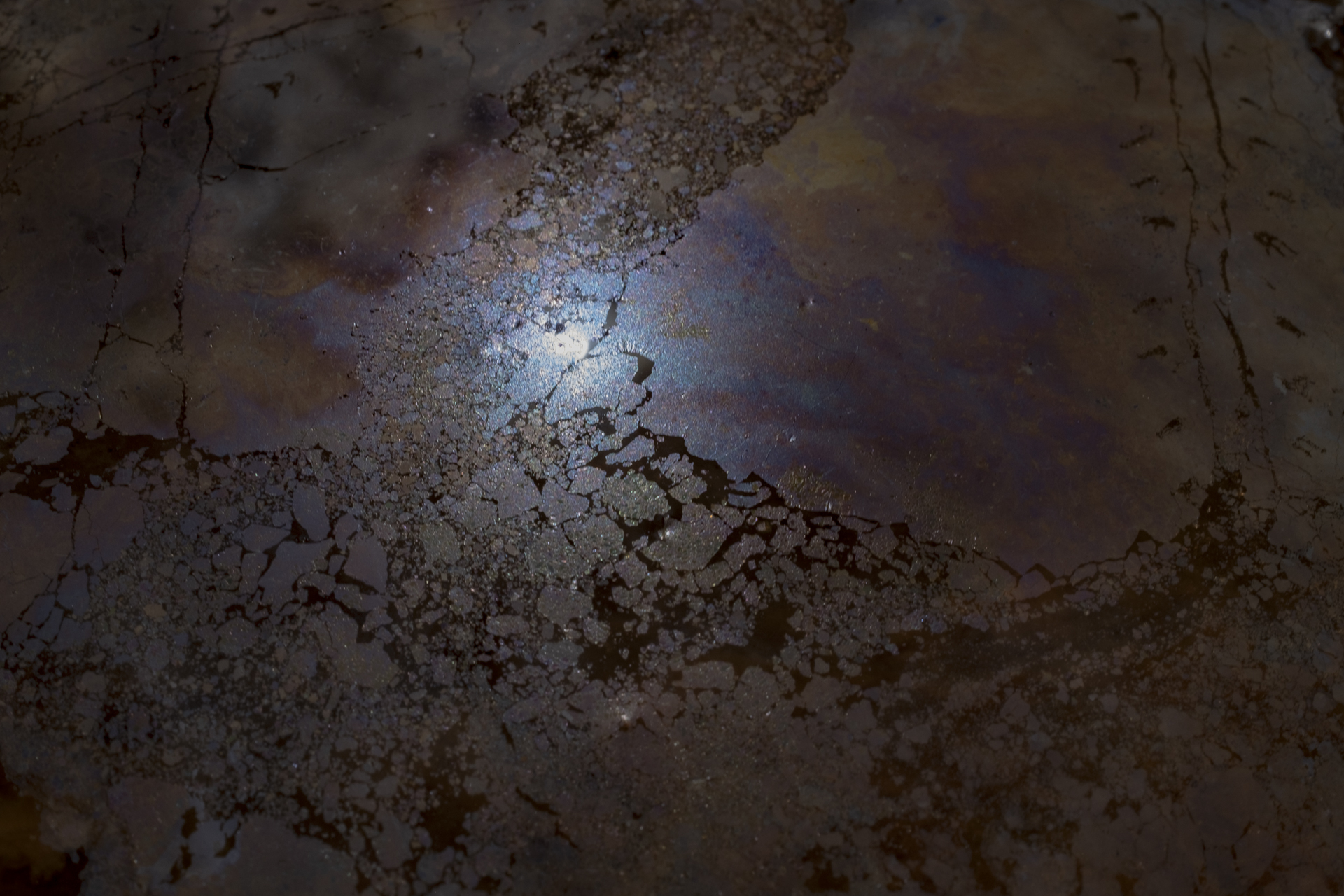

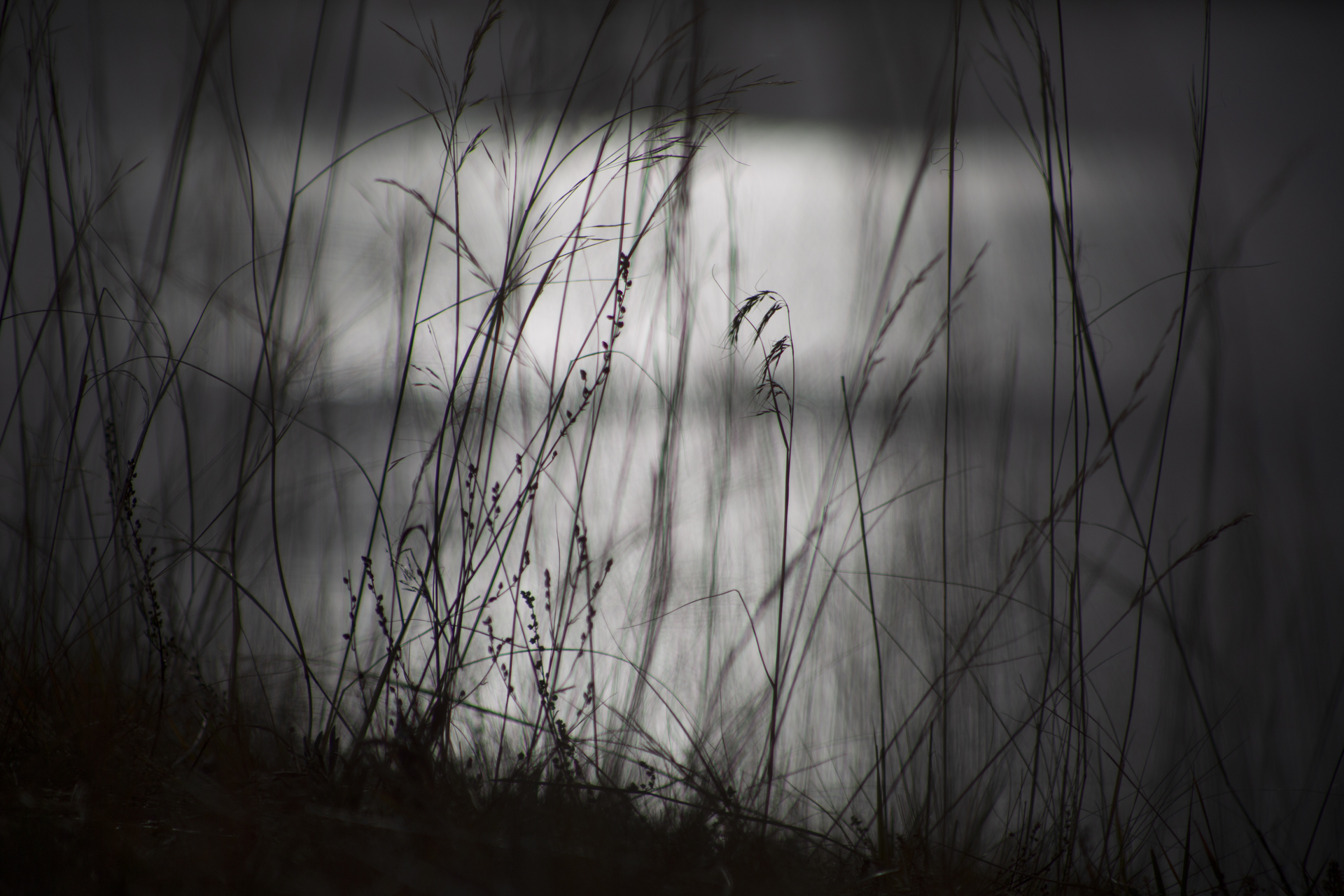

Our parting weeks were filled with nostalgia for the mystery, power and enormity of Baikal, not just as a body of water, but as a living being, a space where spirits rule, a territory where the power of the natural world pervades all the human senses. We said goodbyes to the Angara River, Baikal’s only outlet and the site of exquisite encounters with winter “tuman” or fog (see Cyberian Dispatch 9). We traveled again to Olkhon Island, witnessed a very special ritual in which more than 40 shamans prayed for rain to extinguish wildfires, and paused to reflect in one of Baikal’s most sacred sites (see Cyberian Dispatch 3).

If the spirits of Baikal had the only say, all would be well. Unfortunately, greed, folly, and indifference also hold sway. Our year in Siberia has given us ample understanding of the main threats facing the world’s most important lake: climate change and various forms of pollution that have already damaged shallow areas and now threaten the entire Lake. But the final weeks of our stay also revealed the extent of new, emerging hazards that threaten an exponential increase in harm. These new concerns have unique attributes that reinforce each other and have the potential to rapidly accelerate warming in a “feedback effect.” For example:

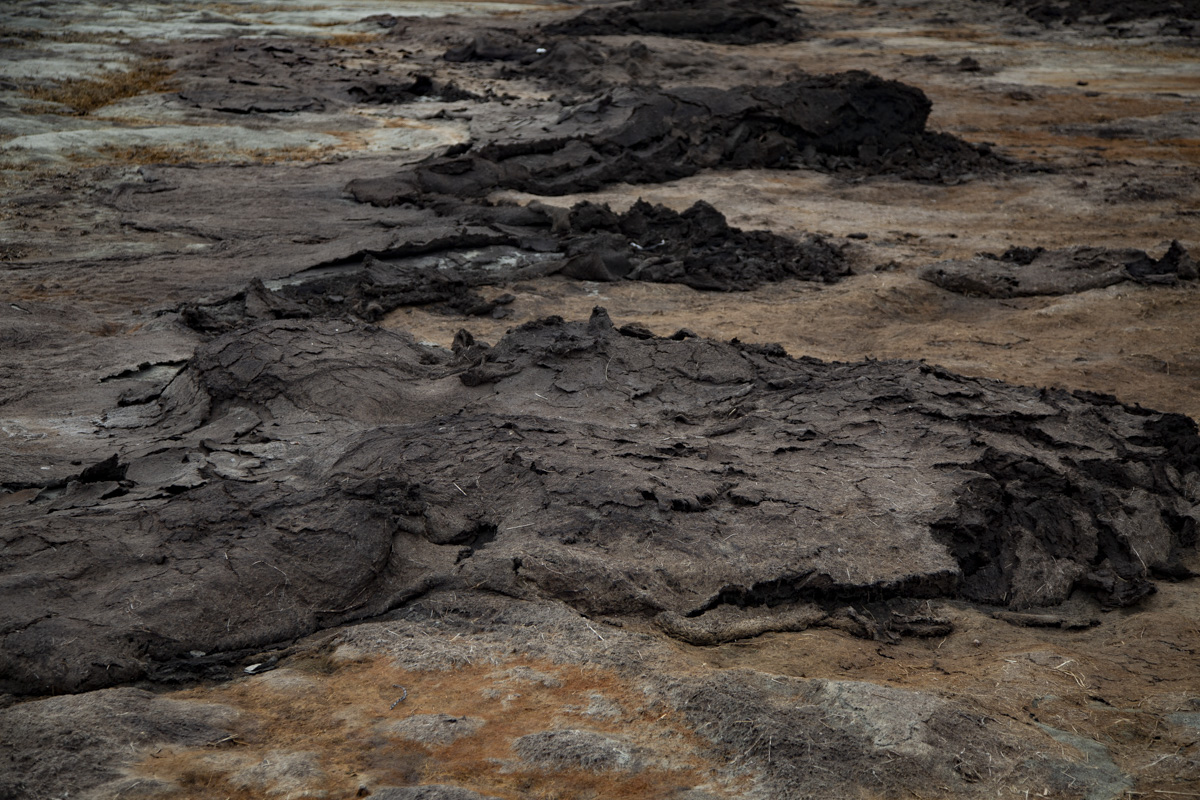

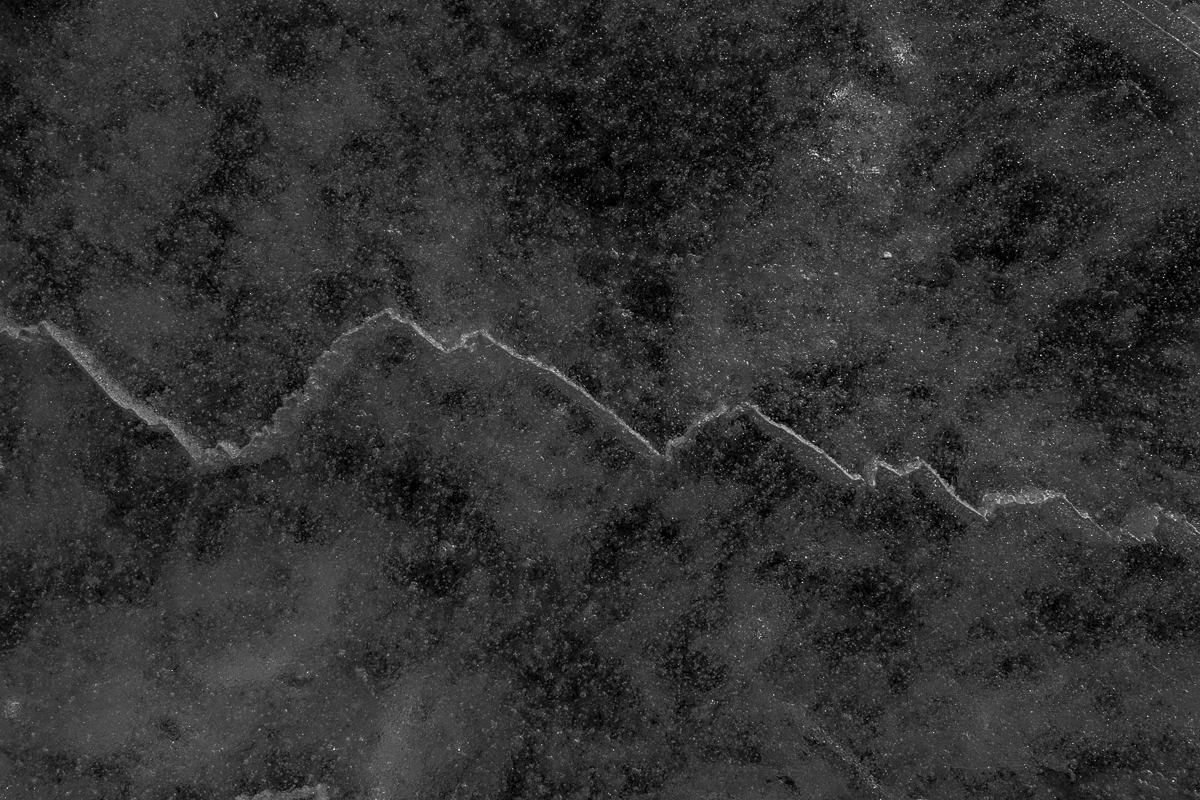

Melting Permafrost: Temperatures in Siberia are increasing twice as rapidly than other parts of the world. As a result, vast territories of previously frozen permafrost are melting, discharging enormous quantities of carbon dioxide and methane -- enough to result in “catastrophic” warming.

Spreading Forest Fires: According to prominent scientists, the growing number and intensity of forest fires is causing “dramatic loss of forested area,” further accelerating climate change.

Excessive Logging: Widespread legal and illegal logging is also contributing to rapid deforestation that accelerates warming; and

Deteriorating Rivers: As temperatures increase, evaporation intensifies and the flow of the Lake’s tributaries is reduced. Dwindling water levels reduce pressure at the Lake’s bottom, releasing additional methane and harming sensitive species.

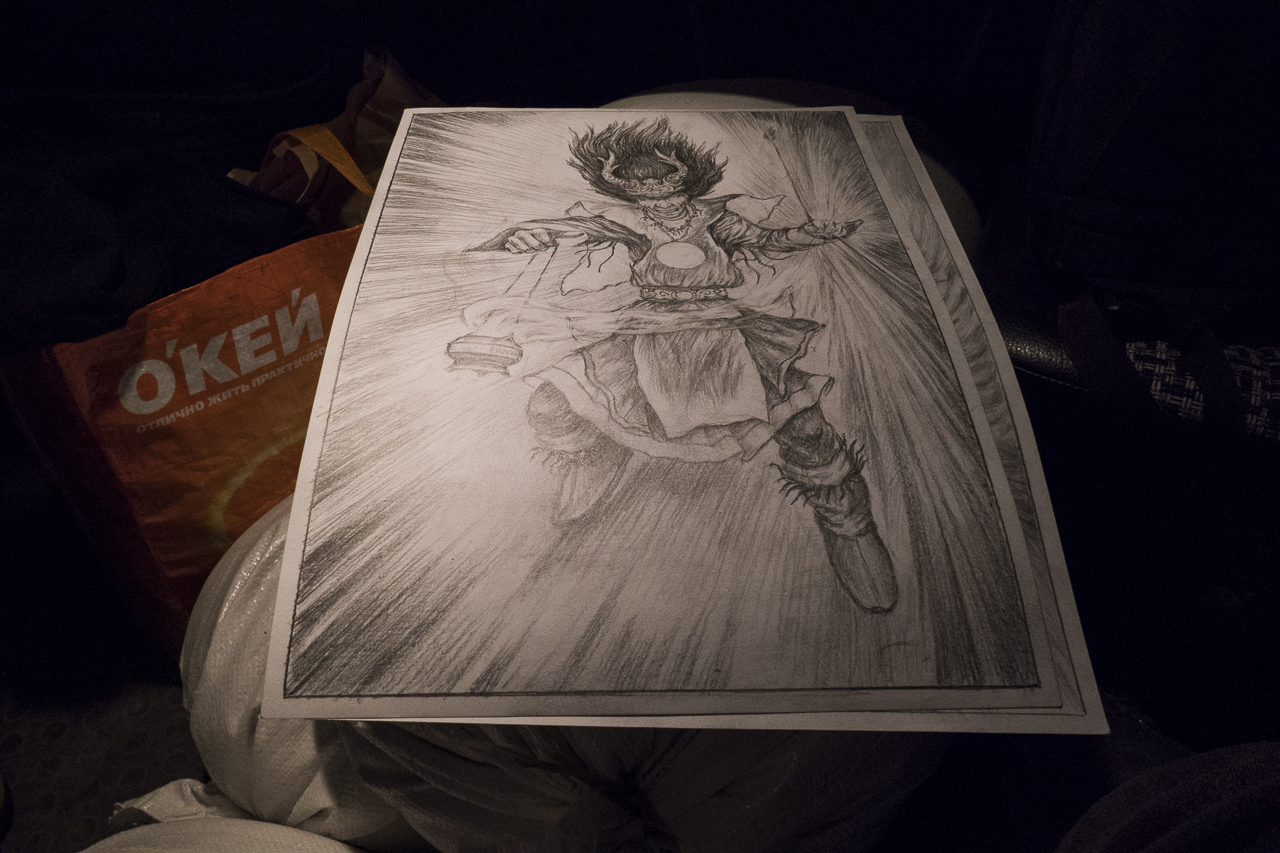

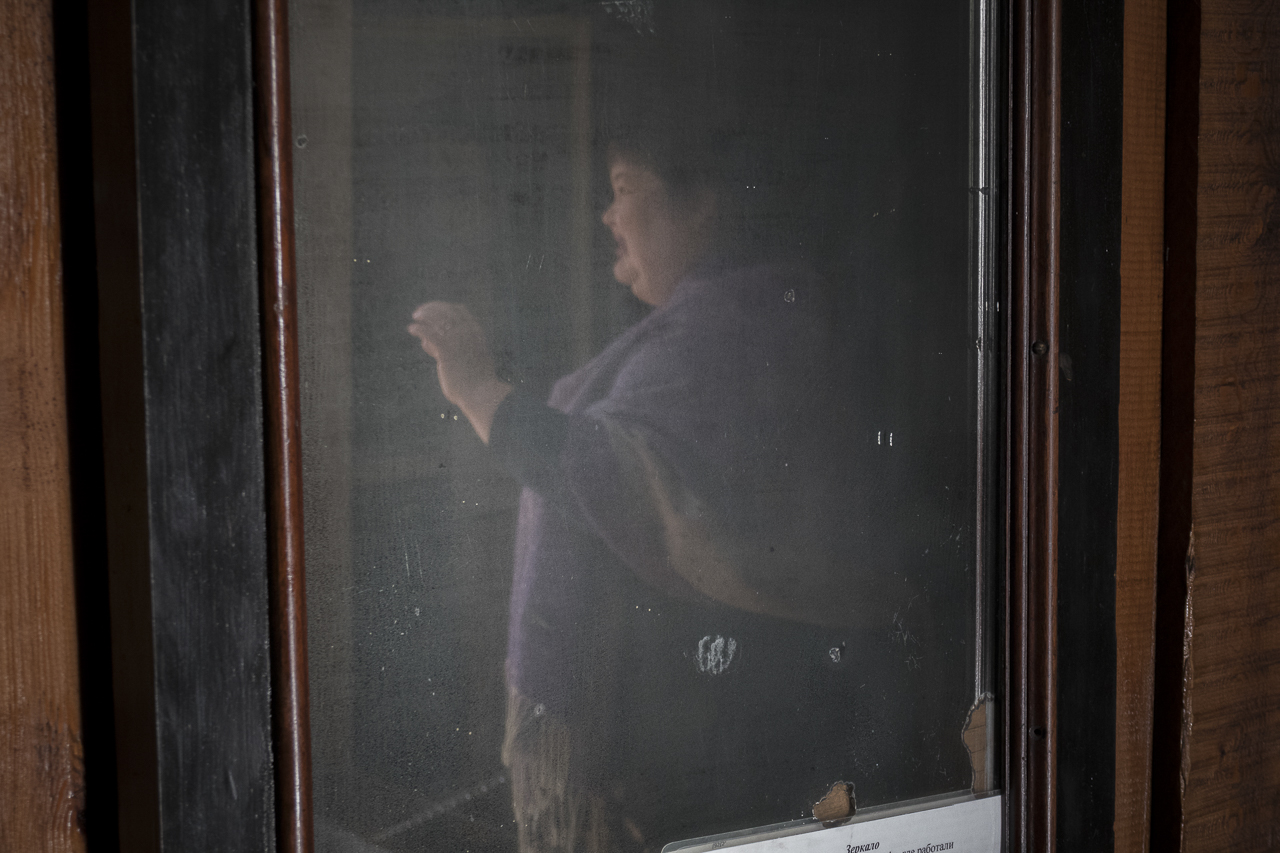

Many of our most memorable moments at Baikal involved sound or music (see Cyberian Dispatch 10). Evgeny Masloboev, an Irkutsk-based experimental composer and musician, can elicit music out of almost anything, including coat hangars, plastic bags, or the leaves of plants. He favors improvisation, and before we left, he very memorably asked us to pull out our phones, hold them near each other, and create music from...a feedback effect.

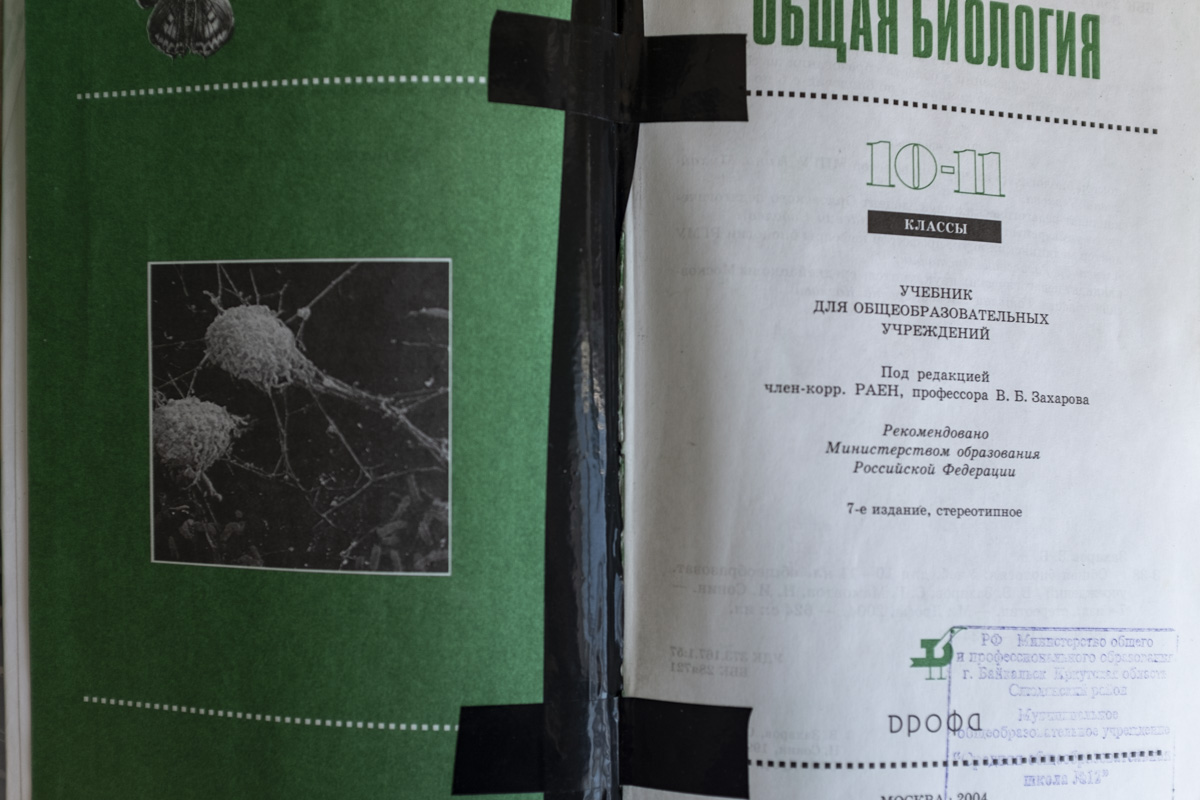

Scientists know that these emerging threats can quickly approach a tipping point that accelerates environmental degradation much more quickly than current climate modeling anticipates. Artists like Evgeny Masloboev sense it and intuitively find a way to express it. The natural landscape already signals distress: people choke on smoke from mega-fires and die when their homes are inundated by flash floods. But in Russia and around the world, many people are not fully aware of how serious the problem is, and policymakers are in denial, immobilized or unsure of how to act on a scale large enough to be consequential.

The swifts departed suddenly one August day, darting into the sky because they knew the environment will soon not be hospitable. Following a small visa snafu, we also took flight to Central Europe on very short notice, uprooting ourselves from our Far Eastern homeland and finding a roost near the Danube River, another threatened body of water.

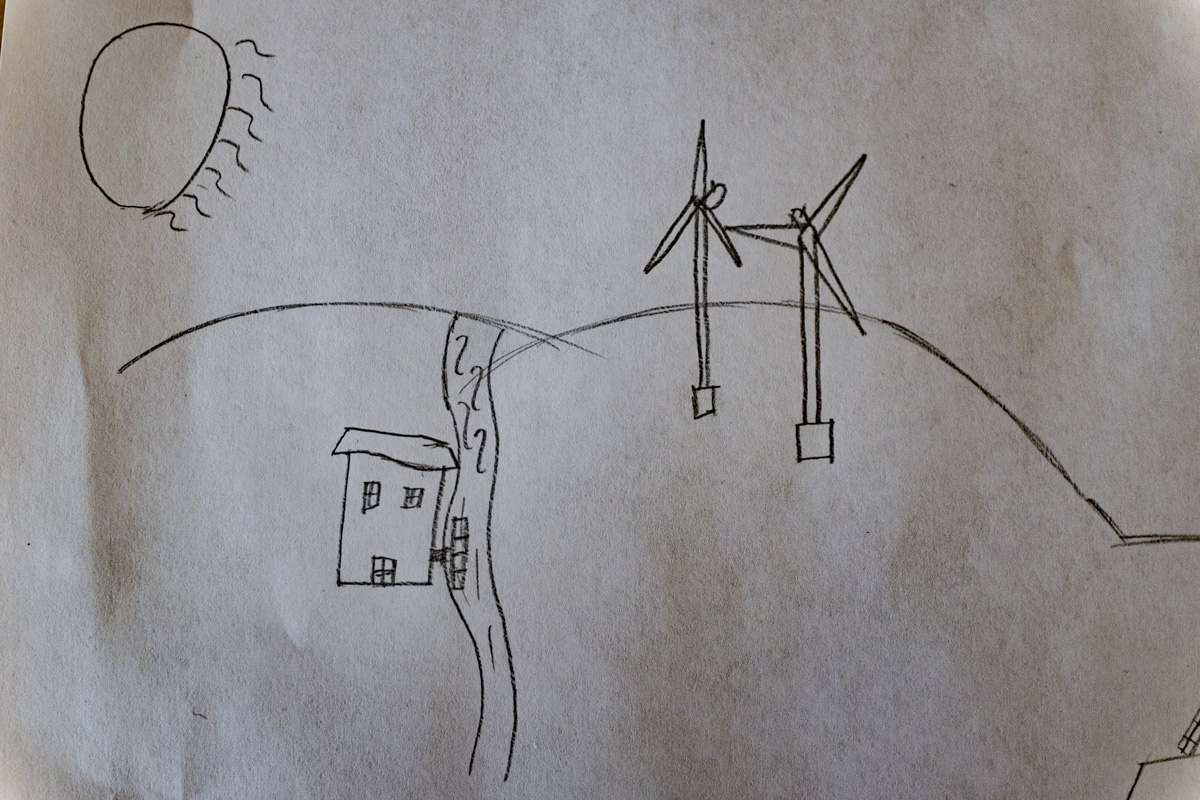

Time is precious now. How can we speed the pace of change on ending the use of fossil fuels and embracing clean energy? How can we embrace the use of alternative energy sources -- ones that are in ample supply in Siberia and many other places around the globe? How can we turn the corner on simple changes like ending the use of phosphates in detergents or stopping the endless stream of bottles that clog our waterways?

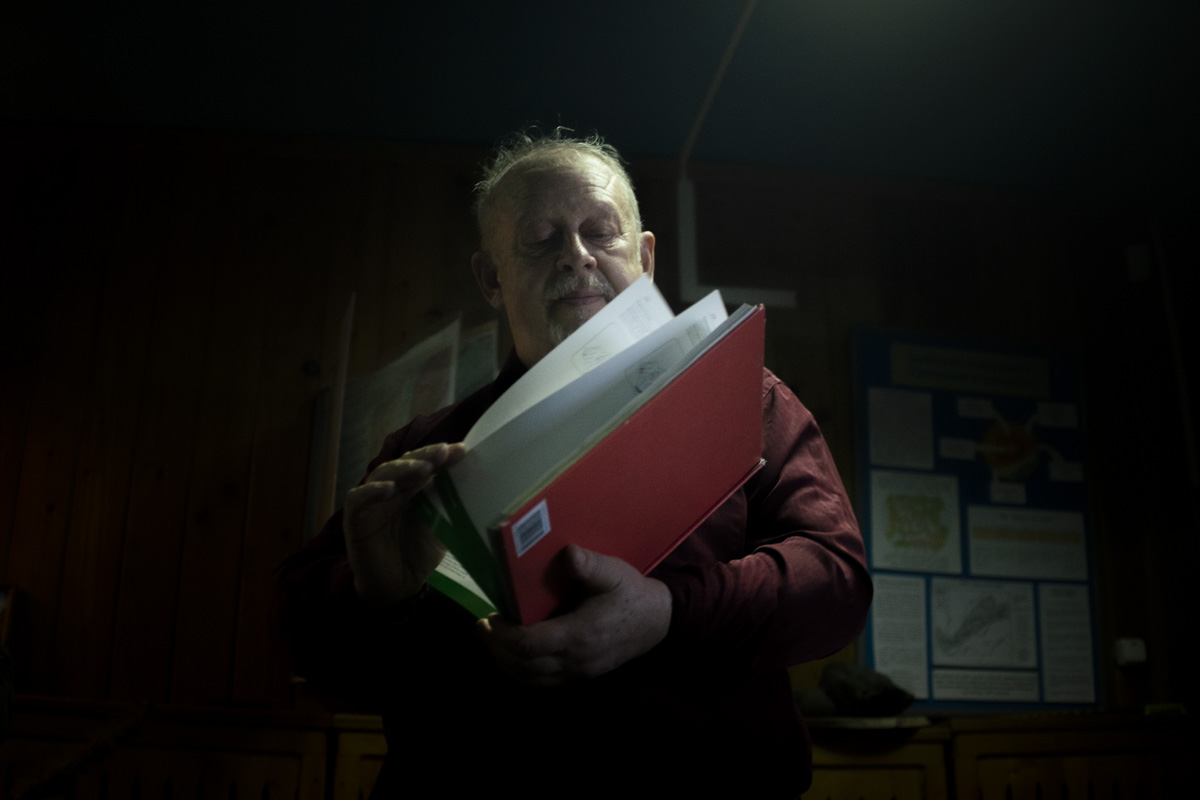

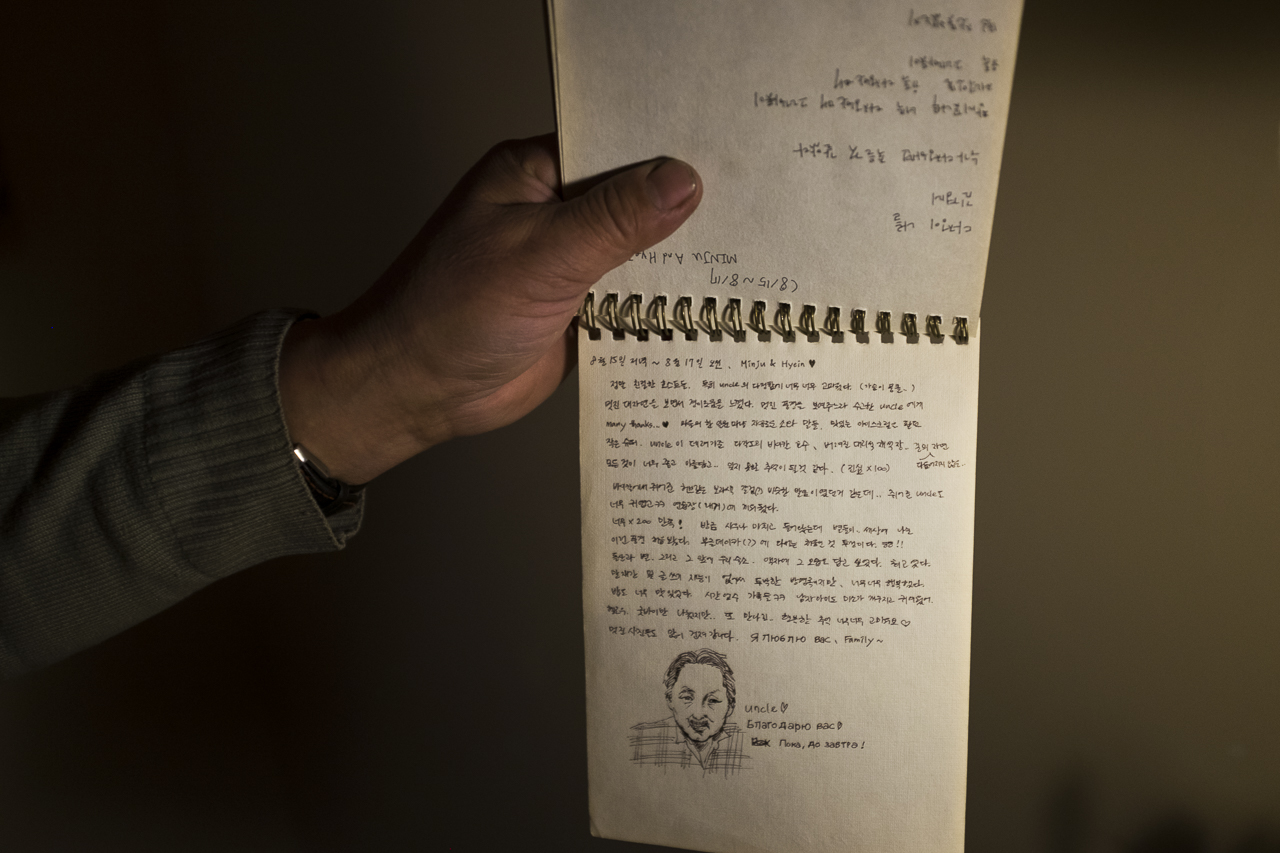

Our year long Fulbright experience proves that we can build alliances across cultures and among diverse stakeholders who share common values and goals. It was an exceptionally meaningful, moving and beautiful experience, and we are forever grateful to our warm, welcoming, and kind Russian hosts, who selflessly ensured the project’s success.

But can those of good faith and good mind work together quickly enough to safeguard Baikal? Can we chart a new course as swiftly as the swifts?