Gabriela Bulisova & Mark Isaac

Especially in its depths, Lake Baikal is still relatively clean. But extensive research by Russian and international scientists shows that it is severely challenged by two pressing threats: rapid climate change that is disrupting its complex ecosystem, and pollution from ever-expanding tourism and development. Also of concern are specific development or regulatory proposals that could accelerate damage to the Lake. While several recent threats have been successfully thwarted, new ones are always emerging, and it is unclear whether activists can stop them all.

A Rapidly Changing Climate

Scientists have ample evidence that the Baikal region is one of the most affected by climate change in the world. One study demonstrates that summer surface water temperatures increased 2.0 degrees Celsius between 1977 and 2003 (Izmesteva et. al. 2016). There is also strong evidence that winter ice cover has decreased in duration and thickness compared with a century ago (Shimaraev et. al. 2002).

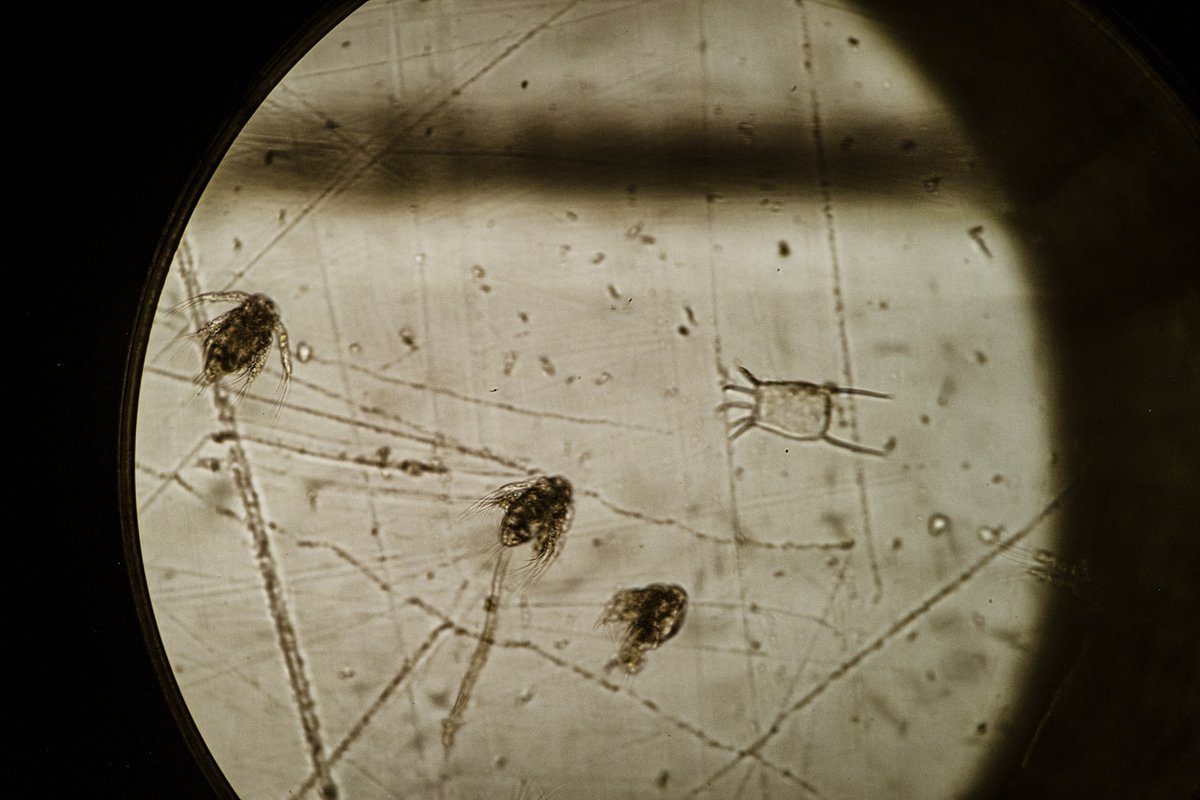

Changes in the transparency and yearly duration of ice as a result of warming have the potential to affect Baikal’s entire food chain. A recent study reveals that small native diatoms (or single-celled algae) that are critical to the food chain are already declining in the southern basin of the Lake (Roberts, et. al., 2018). These organisms provide much of the food for the tiny copepod, Epischura baikalensis, that filters Baikal’s water. Moreover, there is considerable data showing that Baikal’s magnificent amphipods (small crustaceans that are a food source for fish species) are susceptible to severe stress in warming conditions (Axenov-Gribanov et. al., 2016). At the top of the food chain, changes in the ice cover have the potential to harm the world’s only true freshwater seal by negatively impacting fertility and subjecting the young to predators. Moreover, changes in wind speed and direction have the potential to alter the process by which the Lake’s deep waters receive oxygen, with consequences for the entire ecosystem (Moore et. al., 2009).

Growing Levels of Pollution

Pollution is Baikal’s other great threat, creating a range of problems, especially in populated areas and those that draw the most tourists. A variety of pollution sources are already creating negative impacts on sponges, snails, amphipods, and other Lake creatures.

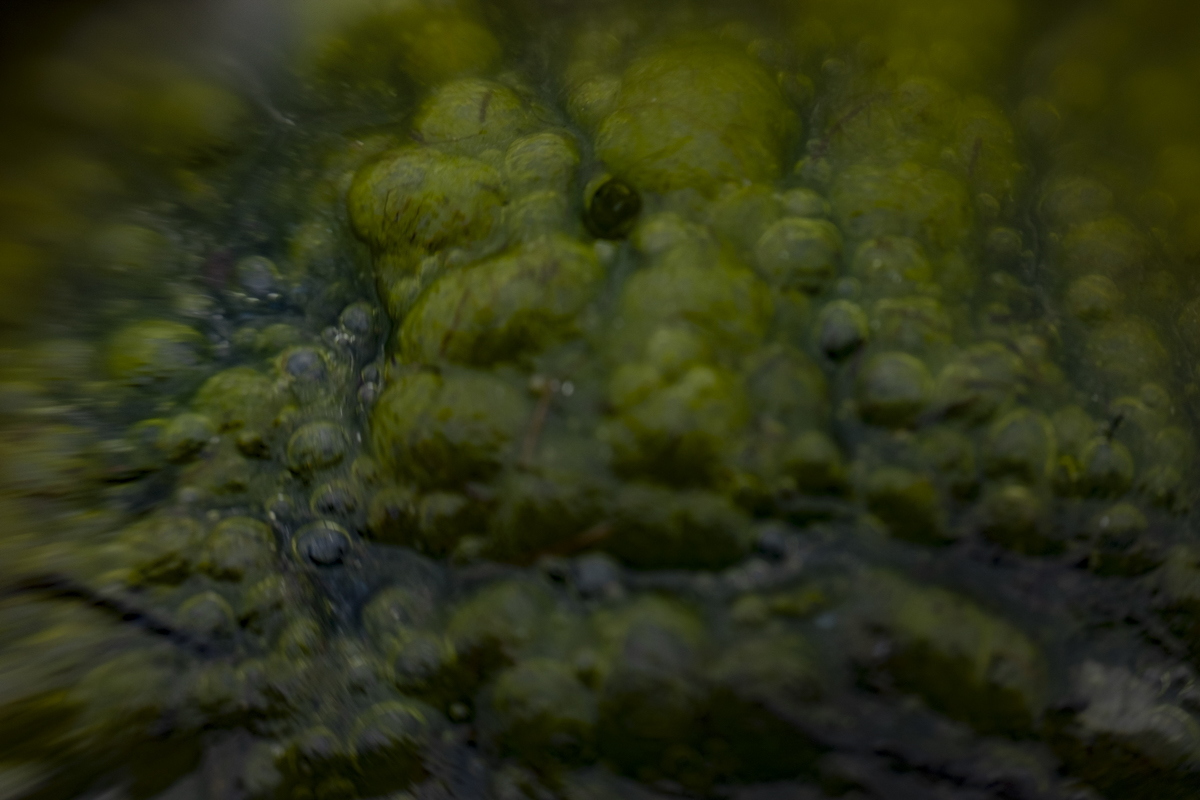

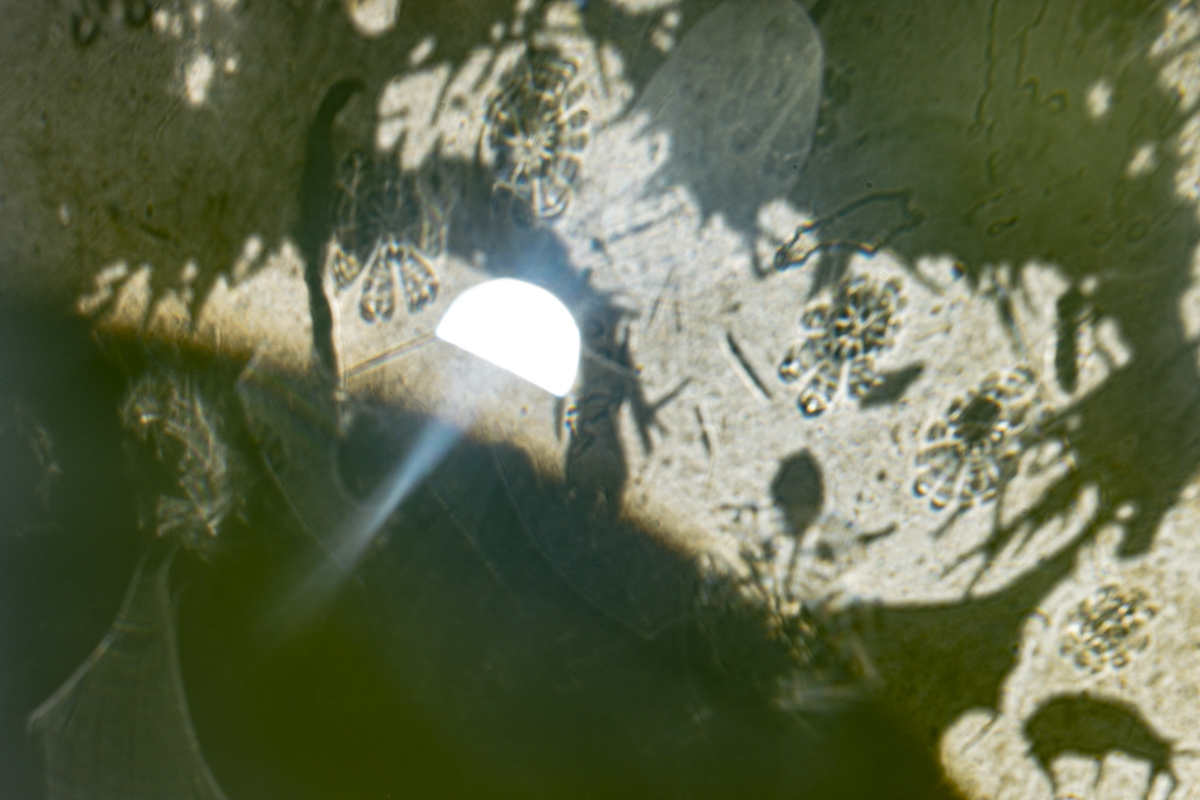

Nutrient inputs are contributing to massive blooms of non-native algae in the coastal areas of the Lake. These blooms choke out endemic species and pose a risk to humans, wildlife, and livestock. There is also a growing epidemic of sickness and death of endemic Baikal sponges and a mass mortality of snails in some areas of the Lake. (Timoshkin et. al., 2016).

Studies show that these problems result primarily from sewage and detergent waste that flows into the Lake from hotels, houses, and tourist destinations. Wastewater treatment in populated areas around the Lake is either lacking or outdated. Moreover, many small homes and businesses rely on unlined pits rather than lined septic tanks, allowing human waste to leach through the soil into the Lake. (Timoshkin et. al., 2018).

A variety of chemical pollutants are also entering the lake, including pesticides (Tsydenova, et. al. 2003) and PCBs (Mamontov, et. al., 2000). Some reach Baikal by air from nearby industrial facilities, but there are also significant discharges of petrochemicals from boats, and dangerous pollutants entered the water when rail cars were washed in Severobaikalsk.

There are inadequate means of disposing of garbage in the Lake Baikal area, and accumulating solid waste is a growing problem in areas around the Lake. Also, tourists are responsible for erosion, damage to trails and campsites, and negative impacts on local flora and fauna. Some of this damage results from inappropriate transportation such as ATVs, which have been banned in some parks.

Synergy Between Climate Change and Pollution

An unfortunate synergy between climate change and other anthropogenic changes poses special challenges the Lake’s future. For example, scientists believe that melting permafrost in the Baikal watershed is a possible source of increased phosphorus and nitrogen in Lake Baikal, contributing to algal blooms. Increased melting of permafrost from climate change may also increase the release of dangerous industrial pollutants such as PCBs into the Lake (Moore et. al., 2009).

Forest fires have also increased in numbers and intensity in the areas surrounding the Lake. Most fires are caused by careless conduct or arson, but they are worsened by a warmer climate. The ash and soot from these fires is likely contributing to blooms of algae in the Lake. In general, a warming climate is likely to exacerbate threats from increased tourism and development, erosion, and other factors.

Damaging Projects and Proposals

Environmentalists have successfully blocked some of the most damaging proposals to exploit Baikal or pollute its waters. In 2008, environmentalists convinced President Putin to re-route an oil pipeline originally planned to come dangerously close to Baikal’s shores. In 2013, one of the most dangerous polluters, the Baikalsk Paper Mill, closed its doors forever, but left behind huge pools of dangerous sludge that are leaking into the groundwater and in serious danger from flooding or earthquake.

A Chinese-owned water bottling plant was recently built on the southern shore of the Lake in Kultuk, in an important wetlands for migratory birds. After protests across the Baikal region and Russia, the plant was blocked from opening because its environmental impact had not been properly studied.

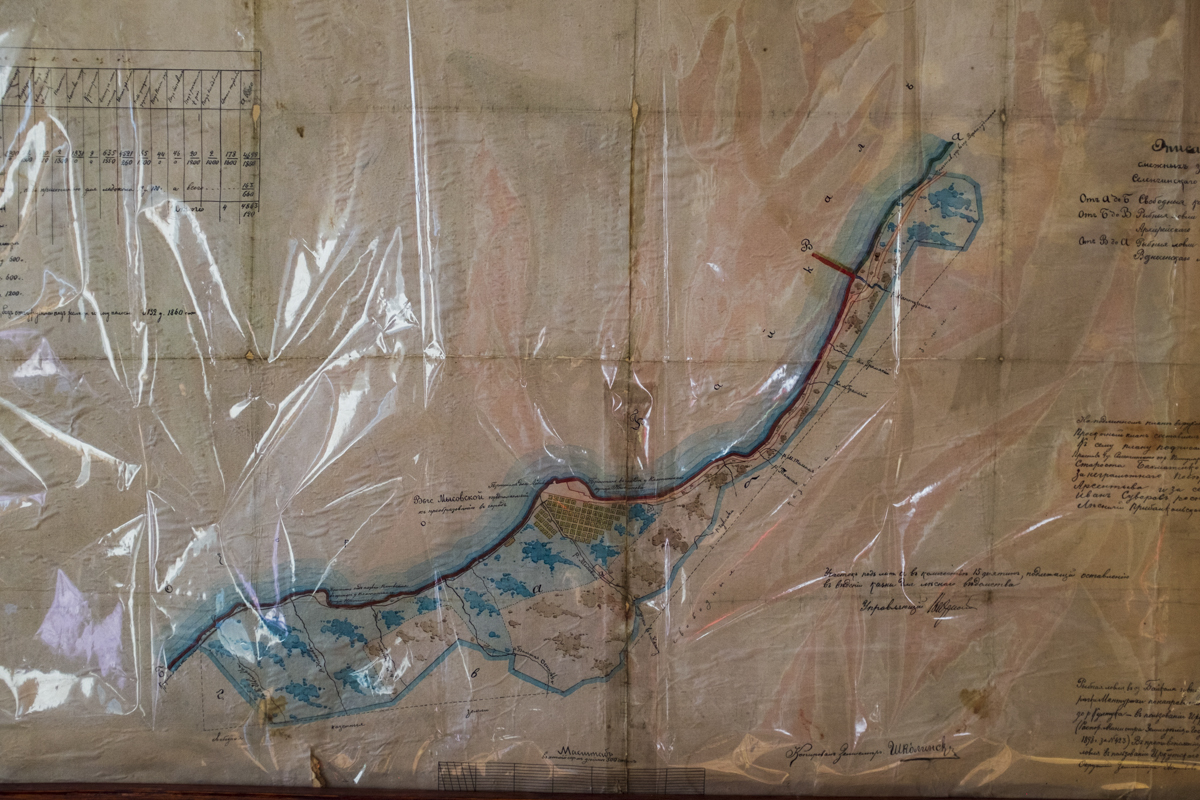

Mongolia has proposed to build up to 8 hydroelectric dams on the Selenga River and its tributaries, the source of 50 percent of Lake Baikal’s surface water. Fortunately, these plans are currently on hold in light of concerns expressed by the World Bank and UNESCO, but Mongolia is intent on achieving more energy independence. There are also proposals to divert water from Baikal to China by way of a massive pipeline. If approved, these projects would lower water levels in the Lake, damage precious flora and fauna, and block migration routes.

But the most important threats facing Baikal at the moment are regulatory ones. In 2018, the water protection zone for Lake Baikal was substantially reduced, allowing considerably more development to occur in protected areas. Now, under the guise of “modernizing” the rules about discharges into the Lake, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment is proposing that allowable releases of dangerous pollutants into the Lake can be increased by as much as 32 times the prior limits. Scientists at the local Limnological Institute and their allies have weighed in with ample evidence that the change would be catastrophic, but no final decision has been made.

Further, some locals bitterly complain that rules about building new structures and boundaries of protected zones are unclear or conflict at different levels of government, so their efforts to create businesses or homes that benefit their families are endlessly blocked or mired in confusion. Rules to protect the Lake must be consistent, strong and fair.

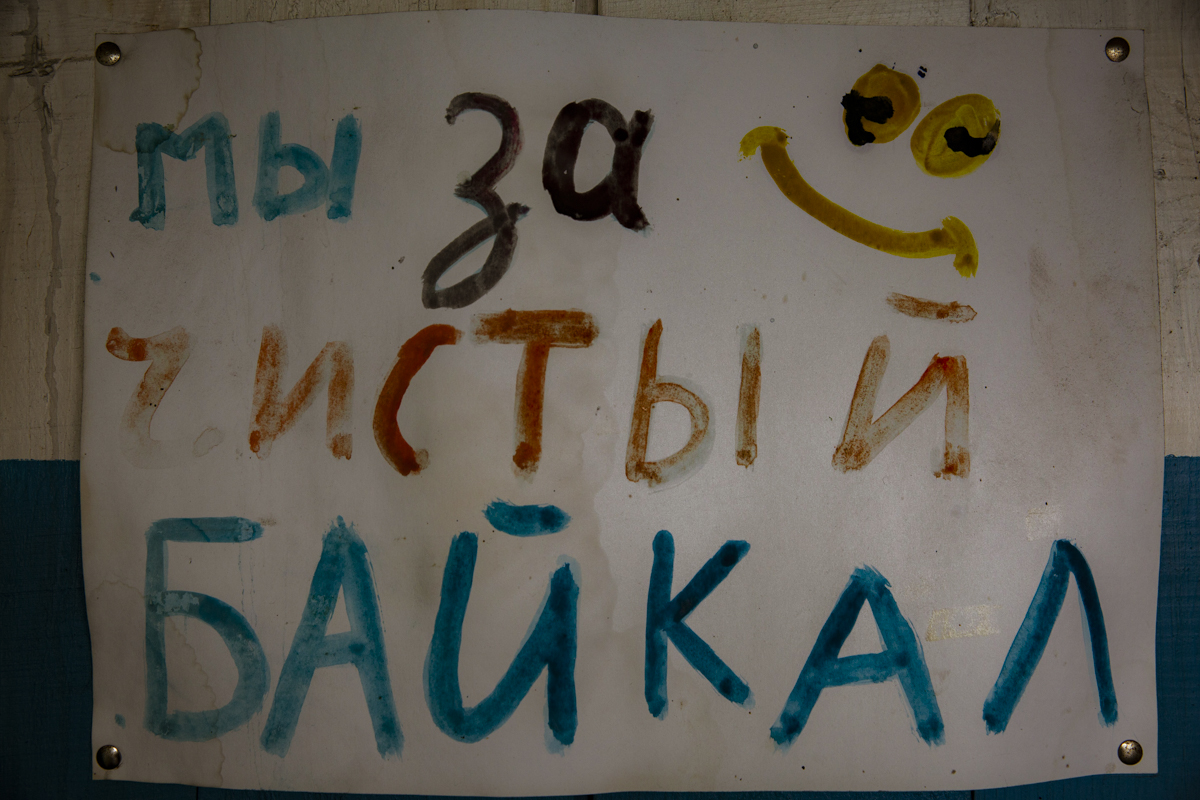

Mobilization Needed to Save Baikal

The combined threats of climate change, pollution, and proposals for harmful developments and regulatory changes not only threaten the health of the lake, but also represent serious risks to future economic activity and human health. A major mobilization is needed to save Lake Baikal, including urgent action by scientists, NGOs, government, and citizens. Here are some action steps that make eminent sense right now:

Immediate steps should be taken to reduce nutrient loading, including substantial funding for sewage treatment. Individuals should end their use of detergents containing phosphates, and Russia should ban the use of these detergents, as was done in the European Union.

Regressive regulatory changes must be blocked and instead replaced with clear prohibitions against damaging discharges into the Lake. Also, policies regarding building in sensitive areas must be clarified so that they can be easily understood and implemented.

Trash collection in the Baikal region must be dramatically improved, and major education campaigns should be initiated to reduce litter in coastal zones.

Strong steps should be taken to enhance eco-tourism opportunities, to provide support for businesses that adopt environmental principles, and to create standards that will help consumers validate their claims. A push toward eco-tourism should include expanded education about best practices for the use of the Lake and its surrounding trails and recreation areas.

The moratorium on dam building in Mongolia should be made permanent, preventing tragic harm to the Selenga River and Baikal.

Strong steps must be taken to prevent widespread illegal logging and forest fires, both of which are widespread.

Action is required to prevent the worst effects of climate change by adopting worldwide policies to reduce carbon emissions and limit the rise in temperatures. Individuals can assist by limiting their energy use and pushing for rapid expansion of alternative energy sources such as solar and wind energy.

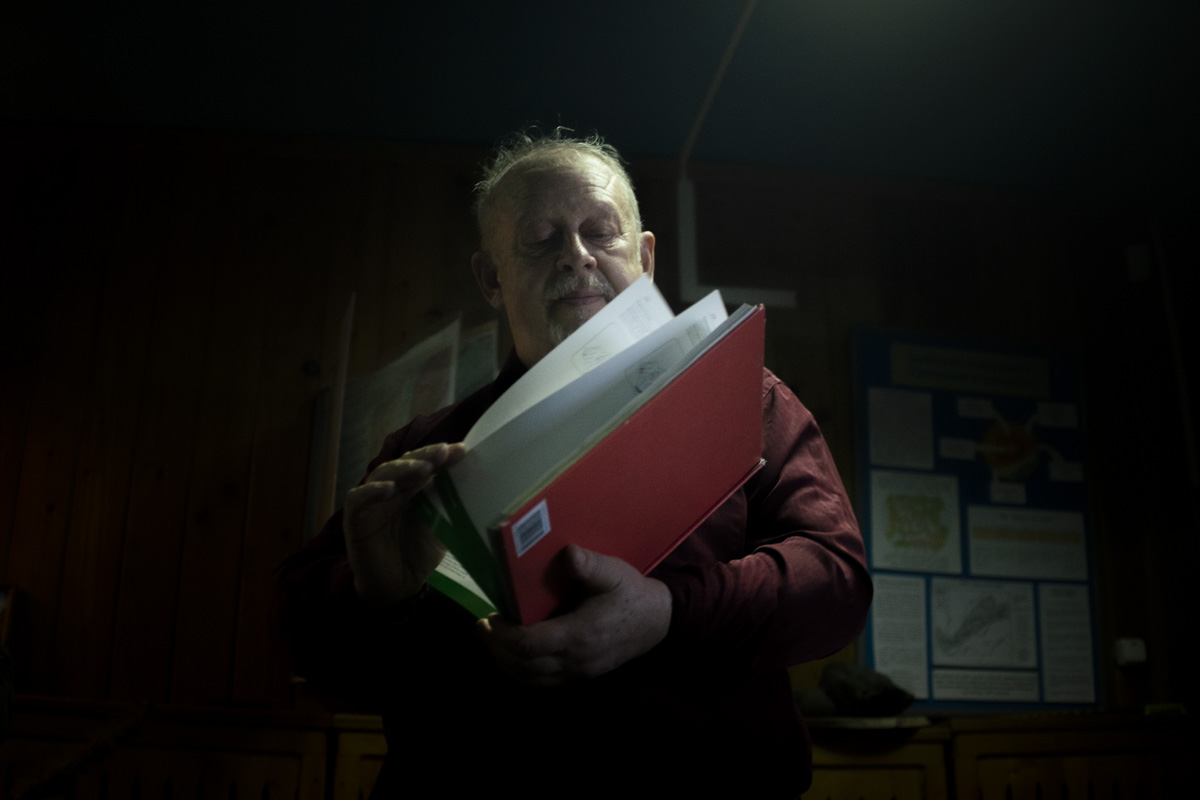

Additional study is urgently needed about anthropogenic changes in the Lake and the impact of climate change, including careful monitoring of coastal and deeper waters. It is essential that Russian and international researchers have ample resources to continue monitoring a wide variety of concerns. It is also urgent that scientific findings be communicated to policymakers and the public in a form that is easily understandable.

Right now we face critical tests of our commitment to preserve the world’s most important lake for future generations. It will be impossible to save Baikal overnight, but an alliance including scientists, environmentalists, artists, and concerned citizens can help make a real difference in safeguarding what Vladimir Rasputin called “the eternity and perfection” of the Sacred Sea.