Gabriela Bulisova & Mark Isaac

As the summer days grow longer and warmer, Siberians of all ages are drawn to the water -- to cool off, relax, and sometimes, perform ancient rituals. And so we found ourselves repeatedly on the banks of the Irkut River, encountering age-old rituals with decidedly contemporary implications.

Among the many peoples who emigrated or were exiled to Siberia, Poles and Belorussians are very prominent. We sadly missed the Polish celebration of Ivana Kupala Night, a pagan fertility celebration associated with the summer solstice. But we were relieved to be invited to the Belorussian version, reputed to be more mysterious and even shocking.

When we arrived along the banks of the river in the suburbs of Irkutsk, women of all ages were already gathering wildflowers and making them into garlands. A huge pile of wood promised a massive bonfire, and elaborate picnics on blankets and in makeshift tents made it eminently clear that many participants would stay until dawn, despite the promised heavy rainfall.

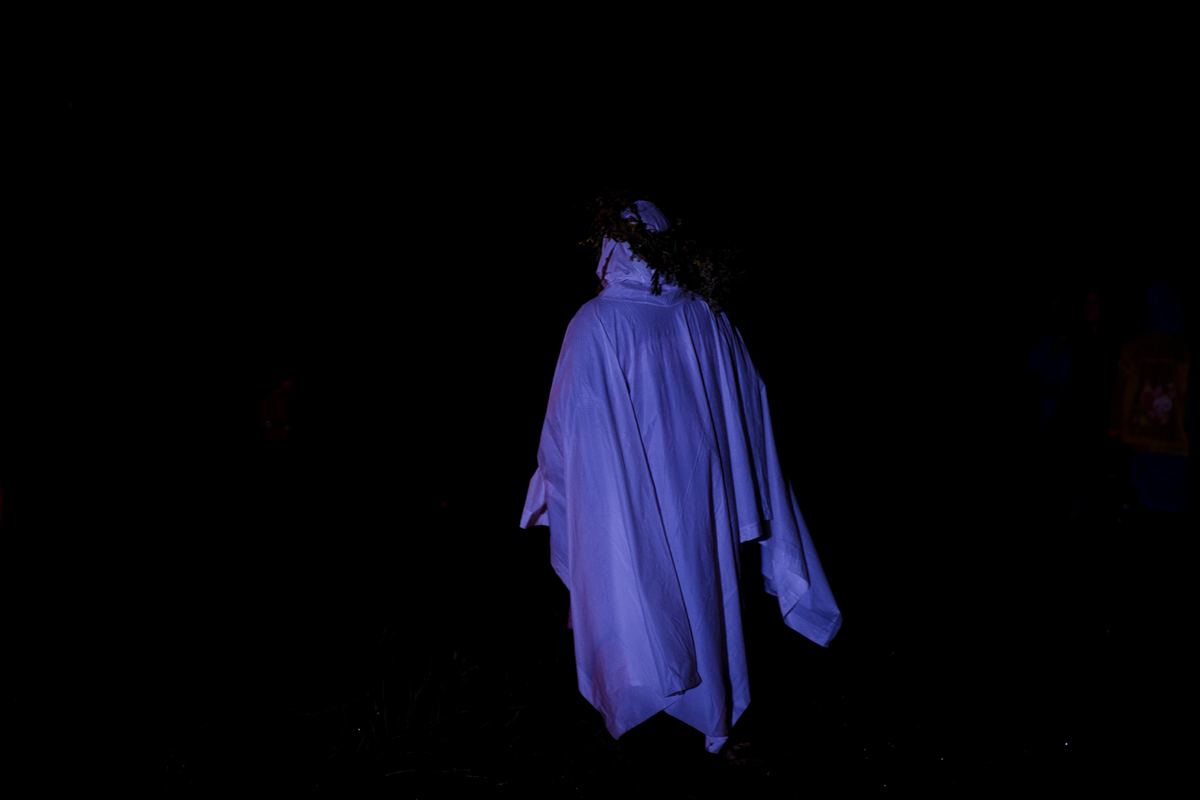

As darkness fell, the rituals got underway. Women crowned with elaborate wreaths of wildflowers formed a massive circle from which men were excluded. As the bonfire was lit, their faces flushed with color, and riotous dancing ensued. Next came games in which men chased women and tried to capture them. As the night wore on, drizzle escalated into rain and rain intensified into a downpour that soaked completely through clothes and shoes. The bonfire leapt ever higher, scattering sparks in all directions, and everyone bathed in the water, light and heat.

Traditionally, it is a night for couples to test their bravery and faith to each other by leaping over the roaring fire. It is a time for women to float their wreaths on the river, and for men to catch them, winning their affections. It is also a time when women enter the forest, followed by men, to seek flowering ferns -- and the possibility of a new relationship. (If a flowering fern is found, it is a truly magical event, since ferns are not flowering plants.) In short, Ivana Kupala is an ancient fertility rite -- connected closely to nature and the seasons. And as our Siberian Belorussians proved, it still resonates very strongly today.

There are two Russian language films we can recommend that touch on Ivana Kupala. For a psychedelic, Soviet-era take on this holiday, try Vechir na Ivana Kupala, created in 1968 by Ukrainian director Yuri Ilyenko. He based his film on a classic story by Nikolai Gogol (which may have also inspired Mussorgsky’s “Night on Bald Mountain”).

For more of a sense of what Ivana Kupala may have historically meant, there is a scene in Andrei Tarkovsky’s masterpiece, Andrei Rublev, in which the painter monk Rublev stumbles upon this pagan ritual, complete with furtive nighttime coupling, in the year 1408. The scene suggests the manner in which pagan worshippers resisted Christianity for generations after it was imposed on Slavic lands from the 8th to the 13th century. For example, some icons of the Virgin Mary were disguised representations of “Damp Mother Earth,” a pagan deity adorned with distinctive six-petaled roses characteristic of pre-Christian faiths. Slavic folk religions, particularly as a synthesis of Russian Orthodox and pagan beliefs, persist to this day, and there is a revival of Slavic native faiths underway in Russia.

Only a few days later, we found ourselves at the spot where the Irkut empties into the mighty Angara -- a sacred spot for Buryats that is used by local shamans to perform their rituals. More than 15 shamans gathered for a very important task. Severe flooding had occurred in the northern part of Irkutsk Oblast, killing approximately 25 people and displacing thousands. The shamans gathered with the purpose of asking the gods to stop any more flooding and to safeguard local people from the rising waters.

During Ivana Kupala, faces flashed in the night with bright colors, vividly bringing the ritual to life. Here the shamans donned traditional vestments, also in dramatic colors, that help them enter into a trance state in which they can communicate directly with the gods, intervening on behalf of local residents. The shamans prepared offerings of tea, milk, vodka, cookies, and the meat of a sacrificial sheep. They lit special herbs and infused the area with their scent. Arrayed in a long line, they beat on ceremonial drums and chanted special prayers. And one by one, assisted by helpers, they entered into trances, hopping up and down and speaking in voices.

The rituals of Ivana Kupala and those of the Buryat shamans are both closely linked to nature, to the seasons, to the natural rhythms of life. They also rely heavily on the forces of fire and water.

When nature is in balance, fire and water help create fertility. The rain feeds wildflowers, couples leap over bonfires to underscore their bonds, and women’s garlands float in the current. But when nature is not in balance, the results are not the same. Right now, in northern Siberia (and other Arctic regions such as Greenland and Alaska), massive wildfires are raging unimpeded across the landscape, burning huge forests to the ground. In Southern Siberia, endless rainfall -- likely accentuated by excessive logging -- is posing a mortal threat, collapsing roads and bridges, and dumping raw sewage directly into Lake Baikal.

The traditional ecological knowledge of long-ago traditions, Slavic and Buryat, teach us to find peace with nature, feel its rhythms, and apply them to our lives. Buryat traditions in particular urge us to take only what is needed and to respect all living things around us as sacred and precious to future generations.

The banks of the Irkut are a fine place for the “good humor mischiefs” of Ivana Kupala. But they are also a welcome spot to relearn the lessons of traditional culture and commit ourselves to basic principles that were never questioned in the past: to live in harmony with Damp Mother Earth and to preserve her fertile treasures for our children.