Gabriela Bulisova & Mark Isaac

Outside of Sukhaya, a village in Buryatia so small and remote that it doesn’t appear on Google Maps yet, we paused at a roadside monument for Khaim, the spirit that holds sway in four local villages. A posted sign warned foreigners who don’t understand local traditions against participating in rituals. But our Russian guide Georgii firmly disagreed, insisting that anyone can and should honor Khaim. We searched our pockets for small coins, often favored in this situation, but found none. Alcohol is suitable, but was unavailable. So a small measure of hot Earl Grey tea was poured from a thermos in Khaim’s honor, also appropriate. Khaim’s sacred location also overflowed with the colorful ribbons that locals tie to trees as a symbol of respect.

During our first trip to Buryatia, several weeks ago, we were enthralled by the virgin ice that had just crystallized. (See our blog post, here.) We were also captivated by the spirit of the place, or should we say, spirits. Each set of small villages has a native spirit who plays an important role there. “We don’t necessarily believe in these spirits,” Georgii clarified, “but we definitely respect them.”

More than 60 percent of Lake Baikal’s shoreline is in the Republic of Buryatia, on the east side of the Lake. Buryatia is sparsely populated, harder to reach, free of the most intensive tourism, environmentally more pristine, and in theory, a homeland for the indigenous people of the region, although many Buryats live in Irkutsk Oblast and elsewhere. It also is a spiritual center, home to a unique mixture of Russian Orthodox, Old Believers (who maintain an ancient version of Orthodox tradition), Buddhists, and people who embrace Shamanic traditions.

As we traveled the coast of Buryatia, the remoteness and the serenity were undeniable, but we also tried to measure the spirit(s) of the landscape. At Vydrino, the border town with Irkutsk Oblast, we crossed the Snezhnaya River on a pedestrian bridge unlikely to pass a safety inspection and marched into the snow-filled woods with Georgii leading the way. We stopped briefly at small lakes created from former quarries, including one renamed Fairy Tale Lake instead of Dead Lake to better attract tourists. Here a sign improbably warned against spearfishing in the ice-covered water. Then we entered a valley in the Khadar-Daban mountain range that dominates the eastern part of the Lake. A long, peaceful hike in the fresh, deep snow brought us to an unexpected obstacle: a mountain stream that could not be safely forded. Instead, we fought through thick brush and ample snow to ascend a small peak with dramatic views of the mountains in all directions.

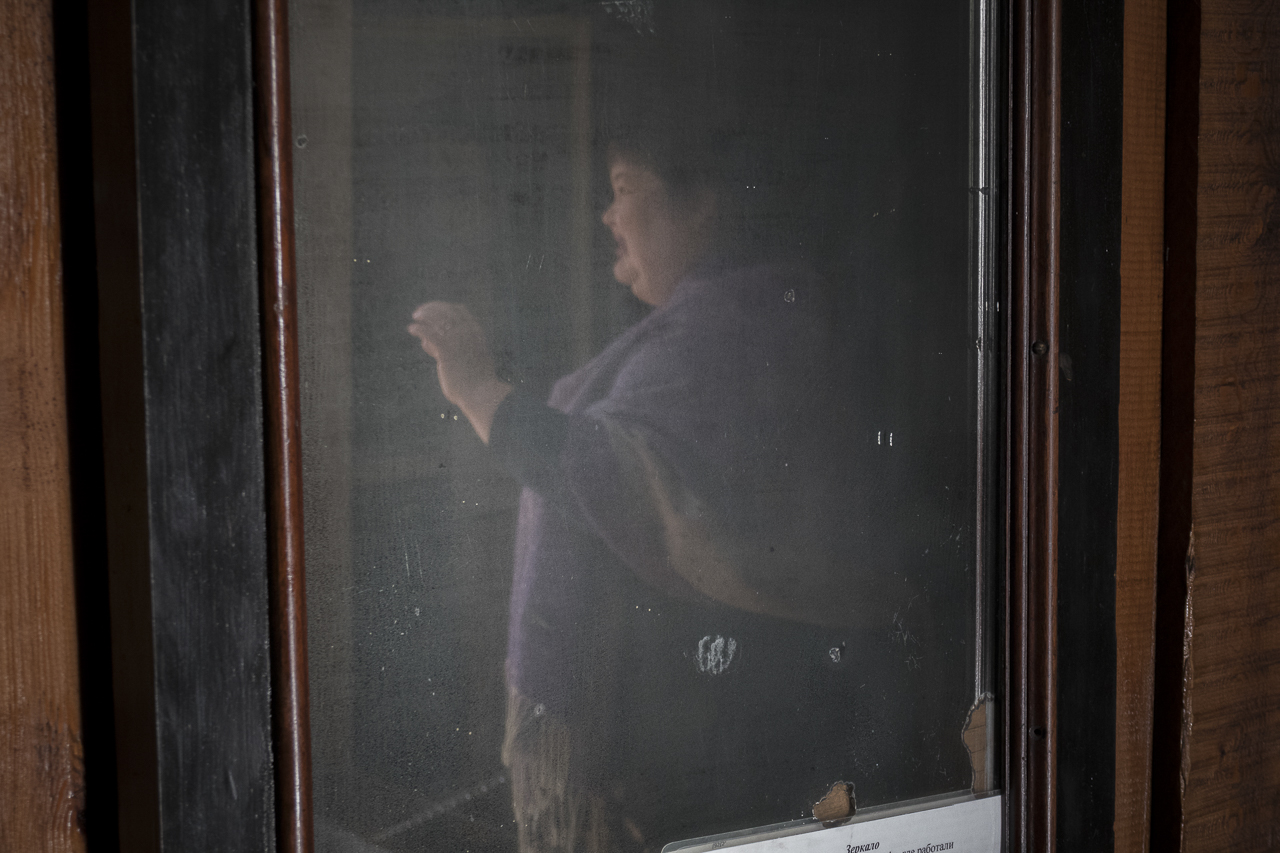

In Tankhoy, a small village adjacent to a nature preserve in the mountains, our goal was also to hike into the mountains, but the preserve has a higher level of protection than a national park, and advance arrangements are required. Instead, we hiked the first and only wooden trail for disabled people in this region, through a special grove created for the protection of Siberian Cedars, which are not really cedars but a hardy species of pine endemic to the region. Except for one woman who crossed our path in the evening, we were satisfyingly alone in meditative contemplation and image capture for an entire day.

In Babushkin, a tiny coastal town, we encountered Marina, the animated and knowledgeable docent at the local museum, who shared artifacts of the town’s relationship to the Lake, including photographs of the oversized ferry that transported people and rail cars across the Lake before the Trans-Siberian Railroad was completed. When asked about the environmental health of Baikal, Marina insisted that the Lake is strong and will withstand any pressures that humans place on it. Then she hosted us on a whirlwind tour of the Babushkin waterfront, where a defunct, graffiti-covered lighthouse can be accessed by climbing a rope 3 meters to its lowest staircase. From the top of the lighthouse, the Lake spread out in three directions, with a scruffy railyard and desolate beach anchoring the scene.

In Posolsk, one of the most ancient Russian settlements in the region, we visited a male monastery of the Russian Orthodox church. In 1651, a Russian ambassador to Mongolia and members of his party who came ashore from their boat were slain here, and there is a prominent monument to their memory. Like many religious sites in Russia, the monastery was commandeered during Communism and has only recently been restored to its original purpose. The young monks continued their daily chores, oblivious to our small group of visitors, and we strolled to the expansive shoreline, bleak, endless and alluring.

Along the main road at Proval Bay is a large wooden monument to Usan-Lopson, the spirit who is reputed to live underneath the Lake with his wife and to rule its waters. Near a caravan still prominently marked with Soviet symbols, workers repaired modest tourist facilities that overlook the spot where, in 1861, a catastrophic earthquake dumped several Buryat villages into the Lake. While most locals escaped, some drowned, and Russian families welcomed homeless Buryats into their homes for the remainder of the winter.

Further north, we visited Enhaluk, a thriving tourist mecca in summer, now frozen and ghostly. Nearby is a hot spring with healing properties discovered when Russians drilled for oil decades ago, and a Buddhist temple that hosts large outdoor meditation retreats in the summer months. Also in close proximity is a monument to the Evenk indigenous people, now dwindling rapidly in numbers. A gate to the monument has tumbled to the ground, and banners with information on Evenk traditions have torn in the wind, but in spite of this, or perhaps because of it, the ground feels weighty and significant.

Finally, we ascended rapidly to the peak of Biele Kamen, or White Rock, where a pale calcium derivative in the stone was used to paint the walls of houses. A local tradition suggests that if you pick up a stone at the bottom of the hill and place it at the top, you will be forgiven one of your sins. On the summit, anthropomorphic towers of rounded stones register as a gathering of tiny penitents lamenting their improper deeds.

Back in Sukhaya, we took note of the uneven pace of development that brought a smooth highway and a blinding array of streetlights, but stopped short of funding wastewater treatment that will protect the Lake from the coming increase in tourism. At the Tengeri Guest House, run by a Buryat matriarch, we settle into a quiet sleep on a hillside near the Lake.

In the night, Mark dreamt that he was on a bus and someone tried to sit next to him. He shooed the newcomer away, thinking he was undesirable, but moments later realized it was Khaim, the spirit of the Sukhaya region. Khaim accepted this affront without taking umbrage. He urged Mark to hold Gabriela tightly and vanished.

In the morning, we awoke to an unending procession of lumber trucks that noisily rumbled past the guest house and faded into a translucent curtain of newly falling snow. We knew without any conscious thought that these trucks, rapidly denuding Siberian forests, do not pay tribute to the local spirits.