“Before I learned to speak the grown-ups in my world stole my language, my right to speak. My mind has always been jumbled with images of Satan and God and my first memory is of fog and images no one else could see. I stopped looking in the mirror when I was 11, until I went into foster care in high school, because my mother told me I had 'seven plus one demons' in me and I could see them so I stopped looking at myself. Can you see that demon to the right? Mocking me. When I turned 13 I started having migraines that felt like if I opened my eyes someone, one of those demons, was stabbing me in my skull all the way down to my eyes. I had no words; just fear, pain and demons reminding me I was damaged. Not even God could love me.” — Taylar Nuevelle

Social Justice, BLM, and Atlantika is a series of posts by Atlantika members that focus on the critical issues of race and social justice. The year 2020 has tragically brought together a pandemic with outsized impacts on communities of color and ongoing protests against the murder of George Floyd and the many others who have lost their lives as a result of racist violence. As our mission statement makes clear, Atlantika members have always valued “social responsibility, community, and nurturing a contemporary humanism through art.” However, in the wake of recent events, which are critical to the future of the nation and the world, Atlantika has renewed its commitment to make racial and social justice a lasting focal point -- and to do our part to bring about a powerful movement for change.

Atlantika Collective members Gabriela Bulisova and Mark Isaac have done extensive work on issues related to mass incarceration, the racist policy that inordinately targets people of color, subjecting them to lengthy prison sentences, often for nonviolent crimes. Their work has included in-depth and intimate accounts of people’s encounters with the criminal justice system, the difficulties faced by returning citizens trying to reintegrate into society, and a special focus on the impact of mass incarceration on children. In this project, titled Who Speaks for Me, the duo collaborated with Taylar Nuevelle, a Black activist who served four-and-a-half years in prison and now advocates to end the “trauma to prison pipeline” for justice-involved women with mental illness.

Please be certain to read the other posts in this series thus far:

Bill Crandall: Minding the Traces

Billy Friebele and Yam Chew Oh: Social Justice, BLM, and Atlantika

Gabriela Bulisova, Mark Isaac and Taylar Nuevelle

One of the most shocking injustices associated with mass incarceration is the fact that our prisons have become a dumping ground for people who have experienced severe trauma, resulting in mental health issues. Instead of receiving the needed treatment, they are subjected to additional abuse and mistreatment. This project is a collaboration with Taylar Nuevelle, who served four-and-a-half years after she was charged with breaking and entering the house of a former girlfriend and attempting to commit suicide. Taylar was diagnosed with PTSD, trauma, and severe anxiety disorder, and a pre-sentence report recommended that she be treated rather than sent to prison, but the judge overruled this recommendation. In prison, rather than receiving treatment, she was raped, locked in solitary confinement and placed on suicide watch.

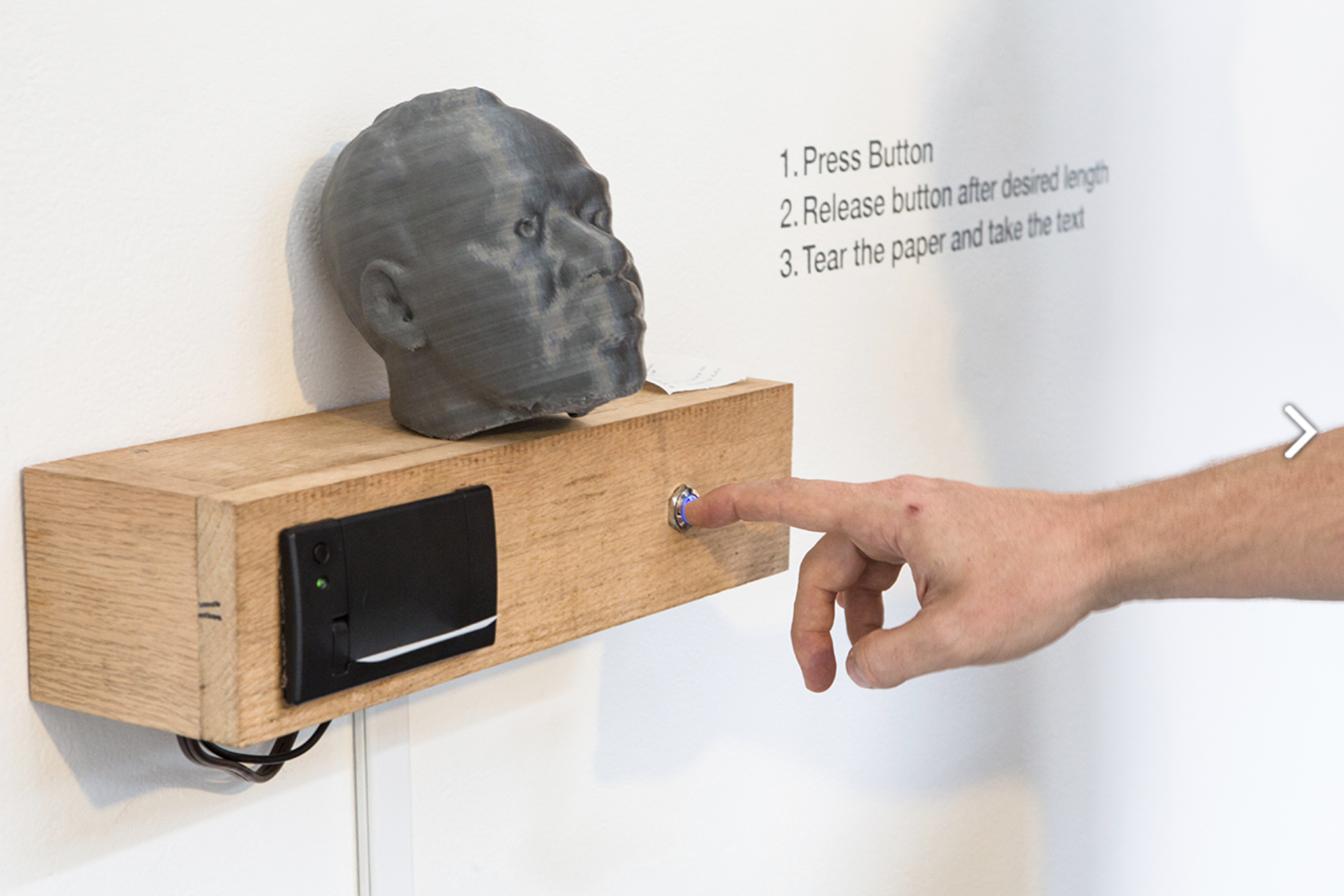

We adopted a novel visual and storytelling strategy that allowed Taylar to personally represent her experiences. First, we photographed her and created digital negatives. Taylar then took the negatives and distressed them to represent her abuse. For example, she used bleach as a means of depicting the times her mother scrubbed her skin with a metal brush and bleach. We passed the images back and forth, working on them until we fully represented her pain. Some of the photographs also incorporate text from her writings and diaries. The final images expose the manner in which our criminal justice system has dehumanized those with mental health issues. By sharing her deeply traumatic and painful experiences with us, Taylar is opening the door for others to find their voices, challenge societal stigma and bring about much-needed reforms. She now leads a non-profit named Who Speaks for Me? that is devoted to ending the “trauma to prison pipeline” for women with mental health issues.

“I’m not afraid to stare down the demons. I’m getting ready. The head is born first then the rest comes. The fog will lift and one day I will walk free and clear. I am giving life to myself and will bury that child born into demon-laced fog and pain.” — Taylar Nuevelle“

“There is not one day that goes by that I do not look at my neck and those small specks of discoloration from birth and not remember. I stand in the mirror fixing my hair, brushing my teeth and saving the jewelry for last because then I have to look and remember. Ajax, S.O.S. steel wool pads and my siblings watching as my mother scrubbed my neck raw down to the white meat. Blood and white and no pain, because she saw dirt where there was just a skin discoloration. 'You always filthy. Now this tha color your neck ‘sposed ta be.' Blood, white meat and no tears--a mother who scrubbed me clean.” — Taylar Nuevelle

See my eye? How many times did Ma make my eyes swell shut? I lost count by age 10. Life for black women and girls is very hard. I can see, not clearly, but I can see I never stood a chance. And I cannot make anyone love me or hurt me.”—Taylar Nuevelle

“I laugh because I am lost and I see the fog demons. Look closer, I am not laughing I am grinding my teeth something I started doing at age two. The grinding focuses my mind and so I am not lost completely to the demons that grow from the fog of violence I was created by and hatred I was born in to.” — Taylar Nuevelle

“I love butterflies. Always, but especially after my son Kalil was born and ‘The Very Hungry Caterpillar’ was our favorite book. See the butterflies above me? I am becoming that beautiful butterfly because I am learning to nourish myself and transform.” — Taylar Nuevelle

“Sepia creeps in because my mind and body were bruised beyond their actual years. I have lived many lives and the aged me is inside of my cracked mind and soul that will never know youth. Sepia creeps in so you can see where I’ve been — never young; never a child. Made a woman before I knew what being a child was all about.” — Taylar Nuevelle

"This is my chest and it bleeds from the inside out. My disability is not apparent, yet it has been present and acute since childhood. As a child I remember when I first started self-harming—I was in the second grade. I used to take straight pins and stick them through the flesh in my chest, cover myself in a shirt and go about my day as the pins tore into my skin. This was nothing compared to the physical violence I endured almost every day from my mother and/or stepfather. The straight pins turned to razors and scissors, and I found release from slicing and cutting other parts of my body. Sometimes life is too painful to carry, and I feel like I might explode and slice here and cut there, and the pain inside will be transformed. I don’t use pins, knives, razors or scissors on myself anymore. I had to stop because I take a blood thinner for a hereditary clotting disorder. My ability to self-harm has been snatched from me, but not the desire. The ache of life’s traumas is etched in my memory and carved in my skin—there will never be relief." — Taylar Nuevelle

"Mug shot of what would be seen of my trauma-to-prison pipeline. Outside the nurse’s office, when I was in elementary school, was a poster titled, ‘Children Learn What They Live.’ I saw this poster often from kindergarten until fourth grade because I became nauseous and vomited often as a child. As I waited outside the office I would read the poster and stop after line seven. Then I would think, ‘There are no good things in my life.’ I knew this by age five. Over the years I have thought about that poster often and then I was given a copy one day while in prison. If mug shots could speak mine would tell you how much I understood as a child about being abused and how often people looked away at the obvious signs that I was living a nightmare. I believed I did not deserve goodness, kindness or gentle touches—Love." — Taylar Nuevelle

"Most scars are easily hidden, but not from the mind—not from my memory. My mother used to burn me with hot combs. These are iron combs placed in fire to straighten the hair and sometimes she burned me with curling irons. Then I went to prison, and there was a woman that worked in the hair salon and one day she burned me on purpose with a flat iron right next to the spot my mother had burned me as a child. This woman in prison laughed and told the other inmates she did it because she did not like my voice and all the hair I had on my head. My mother used to burn me saying, 'All this hair‘n you got a nerve ta be tenda headed. Didn’t git all this hair from my family it’s from yo’ fatha’s side.' Abusers despise me for things I cannot control. I can hide many of my scars, but not from my mind, and it cracks over and over because my memory burns." — Taylar Nuevelle

"The abuse in my family is generational. My great- nephew was born, while I was incarcerated, to my niece who is my older sister’s daughter. When my niece was born, I was in foster care, but I went to the hospital the day she was born and I whispered in her ear, “I will never let anyone hurt you." — Taylar Nuevelle

"After prison, people who you have loved a lifetime have no idea of how trauma before prison merges with prison trauma, and they act and do things accordingly. Twenty-two years of friendship and love. Goodbyes hurt but are also freeing. My beautiful lips (yes, they are beautiful to me) show I’m determined. I can let go. I deserve people in my life as lovely as my lips that ask, 'Who Speaks for Me?'" — Taylar Nuevelle

"I am just learning that it doesn’t get any better just because the sun shines and the rainbows appear. Rainbows and sunshine are not love if they come after you’ve been raped, beaten and told you are worthless—unlovable. Rainbows can be deceitful like abusers." — Taylar Nuevelle