Mark Isaac

It is a time of loss, and even as vaccinated people poke their newly maskless faces into the world and think about new beginnings, we all have a need to process the tragedies that have surrounded us for a seeming eternity -- and threaten to pursue us into the future.

But of course, loss was always with us. And every day and in the course of normal human events, we are faced with the loss of family, friends, acquaintances, those we never knew. We also face the loss of the environment as we once knew it, and the increasing likelihood of epic ecological collapse. We’ve faced a period of endless wars that blended one into another. Each one a tragedy, each a reminder that life can never be immune from death.

Now comes Atlantika member Sue Wrbican, whose latest multi-faceted and highly accomplished exhibit operates as a tool for processing loss. On July 2, her show titled “The Iridescent Yonder” opened in the Riverviews Artspace in Lynchburg, Virginia, a capacious setting that gives ample breathing room to a formidable installation of large-scale sculptures, diverse photographs, and two accompanying paintings by select collaborators. One day later, laptop in hand, she guided us through the show piece by piece during Atlantika’s monthly meeting, elaborating on her inspirations and intentions, and introducing us to some of the people who are central to its themes.

In 2019, within a matter of weeks, Sue lost two close members of her family. First, her brother Matt, an accomplished artist and archivist at the Andy Warhol Museum, succumbed after a lengthy battle with brain cancer. Not long after that, Sue’s mother also passed. The pain of this double loss was searing, but by now it is literally soaring, since Sue seems to have used every available moment of the subsequent lockdown to craft the elements of this show, which include some of the towering cloth sails that have made repeat appearances in her work in recent years.

Oil Tanker, Matt Wrbican, Phil Rostek, and James Nelson. Discarded plastic objects, paint and tar, 192” x 72”, 1991.

The nautical theme is especially fitting in this instance. The entire show is ordered around a very unique and prescient painting of an oil tanker created in 1991 by her brother Matt, along with collaborators Phil Rostek and James Nelson. A looming monolith of a black ship, plying a slick of suspiciously foul and spoiled waters, is visible against a backdrop of conflagration and acrid smoke. As Sue introduced us to this work, held in storage for the last 30 years, it first appeared flat, as many a painting often is. But as she moved her laptop closer, the hull of the ship was suddenly revealed to be a veritable constellation of discarded plastic products, rising off the surface as a bas-relief. And the skilled artists have crafted the oil tanker in such a way that its colossal prow seems likely to escape the picture plane and advance right on into the gallery, sloshing its unctuous cargo on our shoes.

Also on hand was Phil Rostek, one of the creators of this piece, who regaled us with tales of how it was created and how it responded specifically to current events. It was the time of the Gulf War, and our powerful republic had decided to defend its access to inexpensive petroleum. The artists not only greeted this moment of combat and colonialism with appropriate alarm, they were farsighted enough to incorporate a commentary about the pervasiveness of plastic waste, a problem that has in the meantime grown to gargantuan proportions. It is a work whose import has been appreciating every moment that it remained in storage, like a finely crafted spirit aging in a remote cellar.

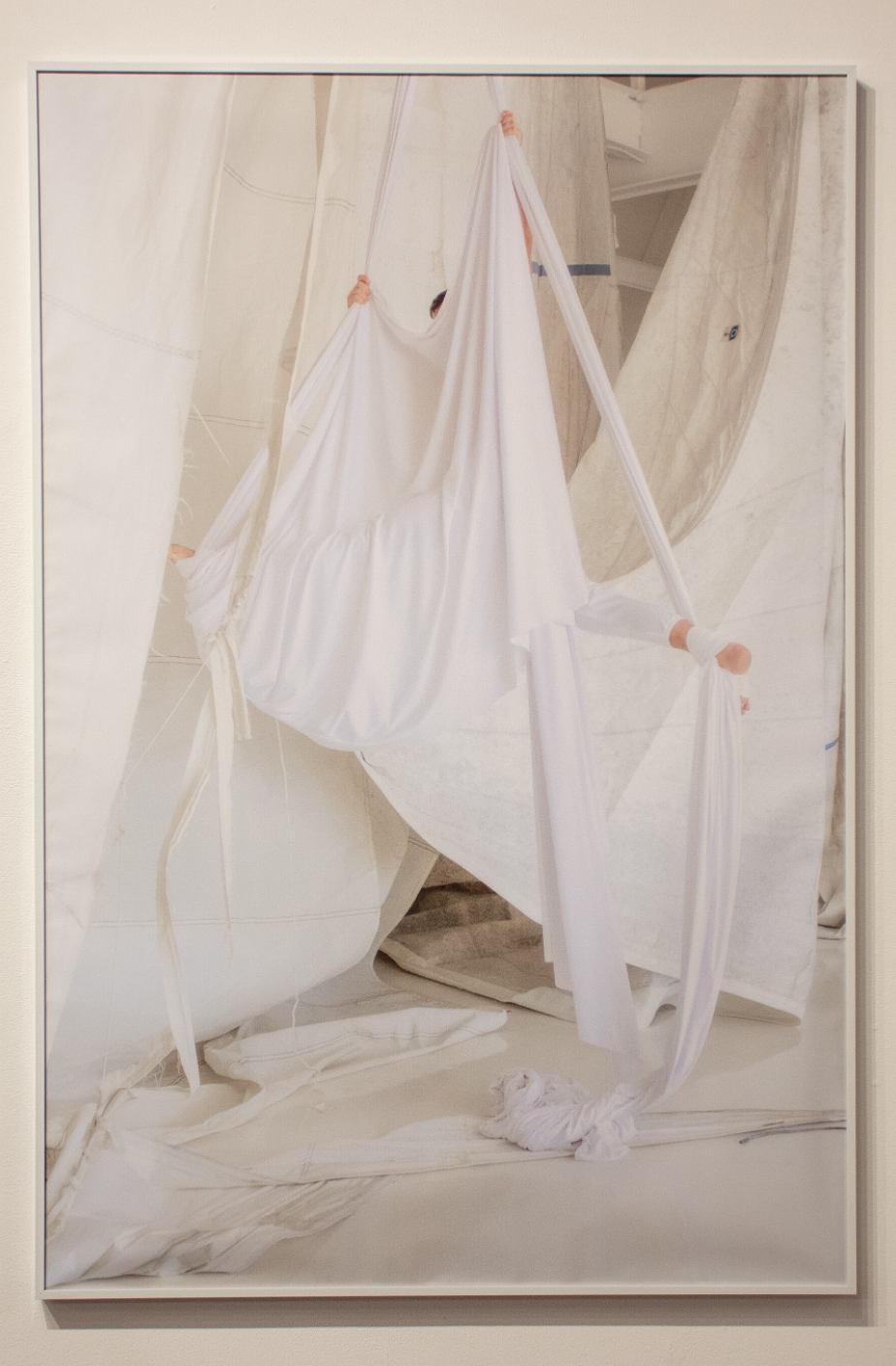

Now all of the artwork gains substance and essence, in proximity to the tanker. The sinuous nautical ropes; the sculptural fish; the dramatic oversize print on silk, laid on the sails like a wardrobe accessory of the gods. The painting of a “Fragile Rainbow” contributed by friend Claire McConaughy in which a reflection of prismatic colors on adulterated water partially vanishes into an ambiguous mire. The photographs that chronicle dystopian assemblages of consumerist waste, yet at the same time point us beyond cataclysm.

Fragile Rainbow, Claire McConaughy. Oil painting diptych, 120” x 40”, 2021.

But let us remember that it is not only the health of our environment that is at risk of loss. The Gulf War was a time of violent loss, as were the many wars that have continued after that time. The battle against COVID remains a time of stunning worldwide bereavement. The many personal losses in all of our lives continue apace through the years, without any cessation. But now, courtesy of “The Iridescent Yonder,” they all come with some valuable tools for processing mortality and moving into a new phase of life. Sue emphasizes that her “quiet, repetitive, meditative process” helped her deal with the pain she was feeling and create a fitting and eloquent tribute to her brother and her mother.

None of us knows in advance precisely how we will react to agonizing loss. But there is something especially eloquent and gripping when human beings do their utmost to overcome adversity, using whatever means is at their disposal. And there is something especially memorable when the tool is gifted and skillful artmaking in which we can all find a glimmer of our sorrow and our yearning to transcend.

In the end, we emerge from mourning with the metaphysical challenge of deciding what to do with our remaining allocation of time. What will we prioritize in the wake of personal losses? Will the post-COVID era be a “return to normal” or will it be a time of change? How will we move beyond the era of endless war? Will we succeed in saving the planet?

In this regard, The Iridescent Yonder offers a subtle but effective push into the realm of action. Set your sails, it suggests. Protest against the intolerable. Safeguard the environment and cherish our fellow human beings. We could take it all sitting down, Sue seems to say, and there’s even a chair if you want to do that. But helpfully a nearby sign advises patrons to “sit with caution.”

The Iridescent Yonder was supported in part by the School of Art at George Mason University and a Gillespie Research Fellowship for exhibition assistance from Michelle Smith.