Joe: So what else is in that mad art history brew? You know I have to ask!

Todd: It’s like a really playful romp through mostly the history of photography, though there are certainly some earlier references as well. Roger Fenton’s “Shadow of the Valley of Death” is something I think about a lot, as well as “Moment of Death” by Capa. In fact I’m hoping to produce a photobook this fall that looks at one of the students of the Bechers, Thomas Struth’s series “New Pictures of Paradise”. They’re these very big, German, sharp pictures of jungles and forests, and I got the book and I ripped out each page, and I photographed it with a pinhole camera. I took this idea of Eden and paradise that he’d made so clear and precise and I tried to romanticize it again. That flip from analytic to romantic again. Like the birds colliding into nets, The World is Round is really about weird collisions of different ideas. I’ve rephotographed Earth Rise [from Apollo 11] in various media and in different ways. Or used a microwave to melt CDs and created a contact print of that explosion.

Joe: One association I had not thought of before in the art historical brew was how much these remind me of daguerreotype portraits. I was thinking about the way the birds appear in some very traditional portrait poses, with a certain rigor. But I think more precisely it’s daguerreotypes, because of the lack of affect in those animals in the captured moment. It made me think a lot about how that visual language of early photography is one that lacks an emotional connection, or is one that we supply in a particular way, sitting alongside the very formal compositions. So I had a good time going through the book again, kind of imagining them as 19th c portraits.

Todd: Yes, there’s definitely a coldness to a daguerreotype aesthetic and to my bird aesthetic as well, despite daguerreotype-mania taking hold in Paris in the early 1840s and the excitement around it, just like my youthful excitement in birds.

Joe: I wouldn’t call it coldness, I’d call it a stillness that was completely technical in the 19th c., but that I read here as scientific and, as you’re saying, abstract and formalized. But I like that overlay of someone who has been stilled for the camera in that moment.

Gabriela: Another phrase I keep thinking about as I look at your images is ‘nature and nurture.’ This is a concept that you’ve been exploring a lot. Can you elaborate on your interpretation and understanding of nurture as it relates to nature?

Todd: Yeah. Some folks hit me on this idea of nurture in relation to the birds because the work seems brutal (but I would argue that we need this knowledge to nurture bird populations). But beyond that point, I’m interested in again thinking of how to walk a historic trajectory, this time from nature or nurture to nature and nurture… It’s tough but interesting to me to take that discourse from the sciences and see how I can map it onto the arts (I think Dennis Dutton did an amazing job of it in The Art Instinct). Each time I think about this relationship between our culture and our DNA, it morphs a bit. I guess you might call my quest for beauty the “nature” in my work. I’m earnestly interested in beauty and the sublime, but I also use it as a hook to attract my viewer to look. The beauty they see is never easy to digest (as opposed to the term “nature porn” that some use when referring to wildlife and landscape photography that doesn’t have an overt critical position). I almost always include visual clues and context that complicate the viewer’s relationship to this beauty, and make them think about the environment side of things: what’s going on.

Gabriela: To follow up, can you talk about your explorations of post-industrial Edens within the concept of nature/nurture?

Todd: I guess there’s also formally wrapped up in the post-industrial Edens and the birds this combination of the grids and these organic branching patterns, and how those two interplay in a myriad ways - as the birds literally crash into these nets and mess up the nets as much as the nets mess up the birds. Or the way that a tree might grow through a fence and create a strange pattern or break through the fence. So how these two systems of interpretation might function together, that are both so critical in terms of how we interpret the world today. Formally, certainly, the grid is the rational (nurture), the branching pattern is organic (nature).

Joe: That metaphor of paradise and Eden you’ve mentioned several times: what is that threading through your projects? How do you think of that?

Todd: It’s one of those penumbral things that if you look at it too directly it will disappear, this idea of wilderness. What pissed me off about the Thomas Struth work is that he was so analytic in his approach to this idea of the prehistoric unknown idea of paradise. It’s impenetrable in the way that his photographs are indeed impenetrable, it’s one of those things the closer you look at it, the farther and quicker it runs away. That’s probably why I’m so compelled to look at it, due to the chase that ensues.

Gabriela: In your projects you also address human impact on wilderness, such as the effect of climate change and global warming.

Todd: Today there is no wilderness, everything is being affected, known, measured. So it only exists in our imagination, and probably on some other planets far beyond human reach! But that unknown, we can’t know it. So I’m trying to focus on weird little edges where we might bump up against it and see it obliquely.

Joe: Do you think we need that space right now? Whether we can see it or not, why do we need that idea of untouched space?

Todd: There’s a part of me that envies the John James Audubon kind of romantic, woodsman explorer tramping off into the unknown. And yes, there’s this idea of exploration and innovation that certainly drives me as an artist and I think drives humanity more generally. So things like the moonshot captured folks’ imagination. I think that aspiration is really critical and crucial, and sometimes today it can become romanticized and backward-looking, which isn’t necessarily a problem, but which could start to be a problem. I definitely find myself actively trying to balance that romanticism and and that forward-looking idea of innovation, and how to walk that tightrope. There’s all these little dichotomies that I try to sneak in back and forth - this spiderweb of modernist specialization going in all these different directions, and I like trying to connect those different directions in weird little tightropes.

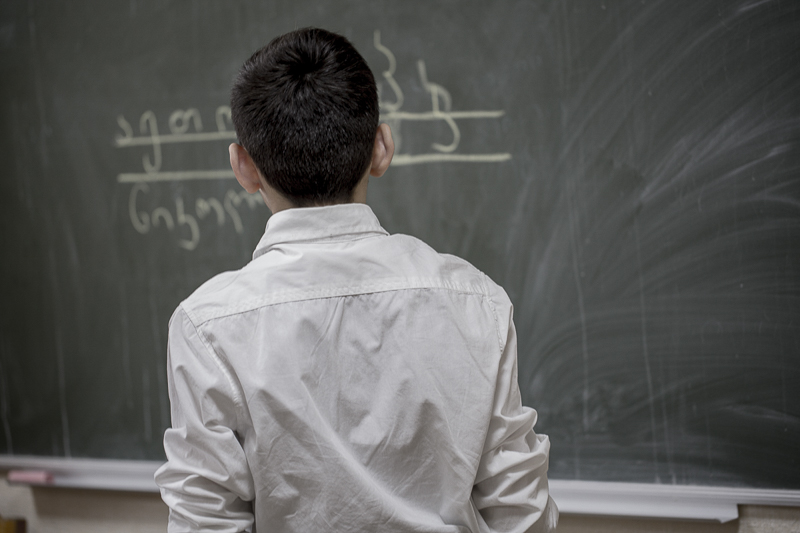

Gabriela: Can you tell us about your choice of different media and processes in your projects? I’m looking again at the Ornithological Photographs, and I’m thinking what would video look like? What would an image immediately before and immediately after the capture look like? How did you decide to choose this specific format?

Todd: It was kind of stupid for me to shoot in large format just because it’s such a pain in the butt with that equipment! And it certainly did make each photograph very precious, since I only shot 2-4 photos of each bird. I think if it were moving, that struggle would become almost too apparent for me, in this visceral, painful way. The stillness negates part of that. But the clarity of it, the fact that I can blow up a print of a bird to make the bird pretty much the size of you or I, creates a different kind of sense of empathy that was important to me. That’s also why I chose a large format as well with the gardens, to take this (in many ways) very banal landscape and present it in a very precious way, to still the constant change that takes place in the garden. In terms of medium these days I’ve just embraced more of the tinkering side, where I am really playing with the history of the medium as well as the future of the medium with the “World is Round” series. Rather than large format, it can be anything from a camera phone and video (though video that is still about stillness) to early non-silver processes.