Gabriela Bulisova & Mark Isaac

The expedition to collect amphipods at Bolshie Koty was led by Ksenia Vereshchagina and Anton Gurkov, scientists from the Biology Institute of Irkutsk State University.

What do peace trails, a strawberry festival and the future of Lake Baikal’s amphipods have in common? More than we thought, it turns out.

Several days ago, we embedded with scientists from the Biology Institute of Irkutsk State University on a one-day expedition to Bolshie Koty, where the Institute has a lab and monitoring station. The main goal of the trip was to capture much-needed amphipods for the Institute’s critical research on the health of the Lake.

In late March, the ice on Baikal was still thick and strong in most places, but driving a car in locations that aren’t regularly monitored is no longer guaranteed to be safe. So, after the one-hour marshrutka ride to Listvyanka, we hopped into one of the many hovercrafts now operating on the Lake. These crafts move easily between ice and water, offering safety that Uaziks (the Russian military vehicle favored on Baikal’s ice) simply can’t offer at this time of year.

A half hour of twisty-turny skimming over the surface later, we arrived in Bolshie Koty, which is accessible only by boat during the summer and ice during the winter. We were picked up at the shores and chauffeured deep into a nearby canyon, along a mountain stream tucked under a rapidly melting ice blanket. Here the scientists had earlier carved a deep rectangular hole in the meter-thick ice, revealing the rushing waters below. This stream is one of more than 330 that feed Baikal, but it is not the pure, virginal water that the scientists coveted. Instead, they were on a mission to find the tiny amphipod (crustacean) named “Gammarus lacustris” hiding below. G. lacustris is not native to Baikal, and experts fear that, as temperatures warm, G. lacustris may move from the rivers, ponds, and wetlands surrounding the Lake directly into its shallow waters, crowding out precious endemic organisms and causing dangerous shifts in its ecosystem.

First, a spear wielded by a young biologist shattered the delicate coating of ice that had formed since their most recent visit. Down went a net, capturing a generous helping of riverbed muck. The muck was deposited on the nearby ice, and several scientists knelt over it, spreading it and poking it with yellow plastic spoons. Several minutes later, a cry went up. A tiny amphipod was found and ceremoniously delivered to a ceramic bowl. Then, several pairs who were locked together in preparation for mating. The scientists found that perplexing since mating usually occurs in May. The process continued, with more and more goo lifted to the surface and meticulously inspected. When 20 amphipods were identified, they were cleaned, wrapped in labeled packets, and lowered into a cylindrical sample case filled with liquid nitrogen designed to keep them alive on their trip to downtown Irkutsk.

After a potluck lunch, we all rushed back to the Lake, this time to gather samples of the amphipods that inhabit the coastal zone. The scientists had arranged with a diver to plunge under the ice and scoop samples of amphipods from the bottom of the Lake. His formidable white mane and moustache revealed him to be in his sixties. Despite the sub-freezing temperatures, he gamely donned aging gear that left part of his face uncovered and disappeared with a sudden splatter unseen below the ice.

A half hour later, he emerged in an explosion of bubbles, bearing a cornucopia of wriggling Lake life. Dozens of organisms were immediately identifiable, from tiny darting crustaceans no bigger than a fingertip, to large, bright orange amphipods with lengthy tentacles and menacing armaments that stretch more than 4 inches long. These were also meticulously sorted, cleaned, labeled and deposited into the sample case in a process that took several chilly dives and multiple hours.

In a flash, the scientists were on the move again, thanking their diving companions, packing equipment and beginning their journey back to Irkutsk, where the amphipods will inform critical research about the impact of temperature changes on aquatic life. Research at Irkutsk State University confirms that most amphipods evolved to live at a specific depth and within a specific temperature range. The Central Siberian Plateau is one of the three areas experiencing the most rapid climate change, and summer surface water temperatures on Lake Baikal have increased by over 2 degrees Celsius over the past 60 years. As temperatures continue to rise, amphipods will be forced to migrate to unfamiliar depths. The result will be competition with other species, loss of population, and disruption of the entire food cycle.

Two days later, we were up early again and on the road to Baikalsk, a city that is best known as the site of a notorious paper mill that was the biggest industrial polluter of the Lake. The paper mill shut down in 2013, more for economic reasons than as a result of ongoing protests. Environmentalists were thankful when it shuttered, but its closure did not end the threat. More than 6 million tons of toxic sludge are stored in unsealed tanks that continue to leach into the groundwater, and they could be propelled directly into the Lake in the event of a mudslide or an earthquake.

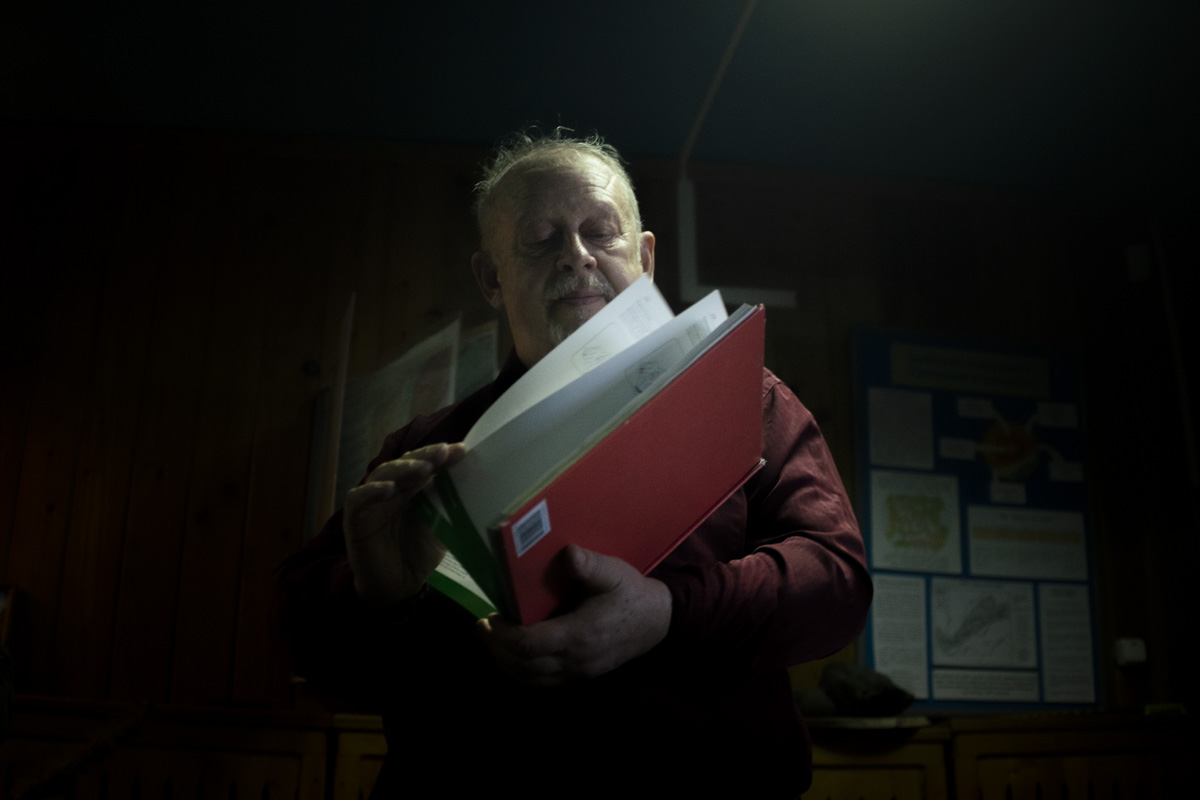

The plant’s closure also created an economic crisis, since most residents relied on the mill for their livelihood. Importantly, environmentalists didn’t forget about these families. They established training programs and incentive grants for former workers to reinvent the economy based on sustainable ecotourism. For example, a program created by Elena Tvorogova challenged local residents to devise plans for profitable businesses that leave the Siberian taiga and Lake Baikal pristine and untouched. The School for Environmental Entrepreneurship has already held 14 session, with more than 600 participants, and it has led to the creation of 28 new startups and assistance for 22 ongoing businesses. Successful -- and sustainable -- new businesses include cycling services, yoga, teas from local herbs, handmade chocolates, wood ornaments derived from logging waste, and oils and butters from local plants.

But the new economy in Baikalsk is wider than these innovative products and services. On the slopes overlooking the Lake, a sprawling resort has opened for skiing and snowboarding. And the city has initiated a well-known festival that celebrates the uniquely delicious strawberries that grow in the Baikalsk area. While many were skeptical it would succeed, the festival now draws significant numbers of hungry tourists each Spring.

And idealistic activists like Evgeny Rakityansky are busy building new tourist trails and bridges in the region with the help of Russian and international volunteers. Rakityansky speaks with glowing pride of the increased safety and improved respect for nature that new trails have created in nearby Sludyanka and Kultuk. But he is most animated when he describes his vision for overcoming differences between nations through shared, loving work in the taiga. His summer camps for trail construction have already drawn participants from more than 10 foreign nations including the United States. With two trails already close to completion, he is now planning a trail in Baikalsk, and he is initiating a reality show on YouTube that will unlock the “inner spiritual code” of the landscape.

Throughout the Baikal region, environmentalists have a vision of creating a future of ecotourism that brings more visitors to support local residents and minimizes their ecological impact. But an economy that goes beyond slogans to build genuine ecotourism is difficult to forge. One activist, Roman Mikhailov, defines authentic ecotourism as a low-impact form of tourism in which participants enter wild nature, leave no trace, learn from local people, and provide concrete benefits for the local community. However, the number of visitors is expanding much more rapidly than strategies for minimizing their impact. As many as two million visitors arrive at Baikal each year, and the New York Times named Olkhon Island to its list of the 52 most important places to visit in 2019. Tourists arrive in a region where most businesses haven’t ever heard about ecotourism, let alone implemented its principles.

Baikalsk, with its many initiatives around sustainable development, is in the forefront of efforts to jump-start ecotourism in the local economy. Elsewhere, in places as far-flung as Listvyanka, Buguldeyka, Bolshoe Goloustnoe, and other locations around the Lake, a new style of guest house offers home stays or lodgings for only a few tourists at a time, a welcome alternative to the large hotels that have proliferated in recent years.

These promising initiatives represent real progress. But to implement full-fledged ecotourism, attractions around the Lake need to do even more. Research shows that waste leaching from guest houses and homes is the main source of nutrients that create widespread blooms of algae around the Lake and choke endemic coastal organisms. It’s essential for tourist enterprises -- and the government -- to embrace rapid advances in sewage treatment, septic systems, composting toilets, and strict limits on discharges into the Lake. It will also be important to offer tourists some form of an ecological rating system, so they know which claims about ecotourism match actual practices.

Right now, peace trails and strawberries are leading the way toward a more sustainable future, but these valuable initiatives can’t keep pace with the increased burden on the Lake. If we hope to save Baikal’s precious amphipods -- and its singular ecosystem -- we must wriggle free of our current thinking and make a rapid leap forward on eco-tourism.

Baikalsk, the site of a shuttered paper mill that once was the largest source of industrial pollution in Lake Baikal, is trying to reinvent itself as a center of sustainable development and ecotourism. Environmentalists are in the forefront of efforts to train a new generation of socially conscious entrepreneurs.