Todd Forsgren

While writing this post, it has been raining in Los Angeles and much of America has been plunged into a deep freeze caused by the break-up of “the polar vortex.” But these bits of weather are at odds with the broader trends happening in our climate right now.

Last year I moved from Washington DC to Los Angeles, California (although when my current President talked about “draining the swamp,” I assume he was thinking about folks with more political influence than me). So, for my first post to Atlantika’s blog, I want to reflect on moving from a city built near a swamp to a city built in a desert, and the urbanization and development of the American landscape in between DC and LA. I think that this resonates with my interest in contributing to the Atlantika Collective, as well as recent changes in Atlantika’s vision and scope.

I lived in DC for seven years. That’s longer than I’ve lived anywhere aside from Ohio, where I grew up and my parents still reside. So, DC was home. I formed a lot of very meaningful relationships there... It was where I met many of the founders of Atlantika (you may remember I was interviewed by Gabriela Bulisova and Joe Lucchesi a few years back).

My photographs have long been about climate change and globalization. I’ve photographed urban and community gardens in Cuba, Mongolia, Europe, Japan, USA, and elsewhere. I think that these tiny patchwork gardens seem to exemplify the environmental mantra of “think globally, act locally” and that such gardens will become an increasing necessity for food security as our planet’s population increases. Then there are my Ornithological Photographs, images I made alongside bird scientists that consider the abstraction from individual bird to concerns for species and ecosystems. My World is Round project is a more direct confrontation of this battle between the senses and reason/data. All three of these projects consider how hard it is for us humans, observational creatures by nature, to really grapple with abstract thinking.

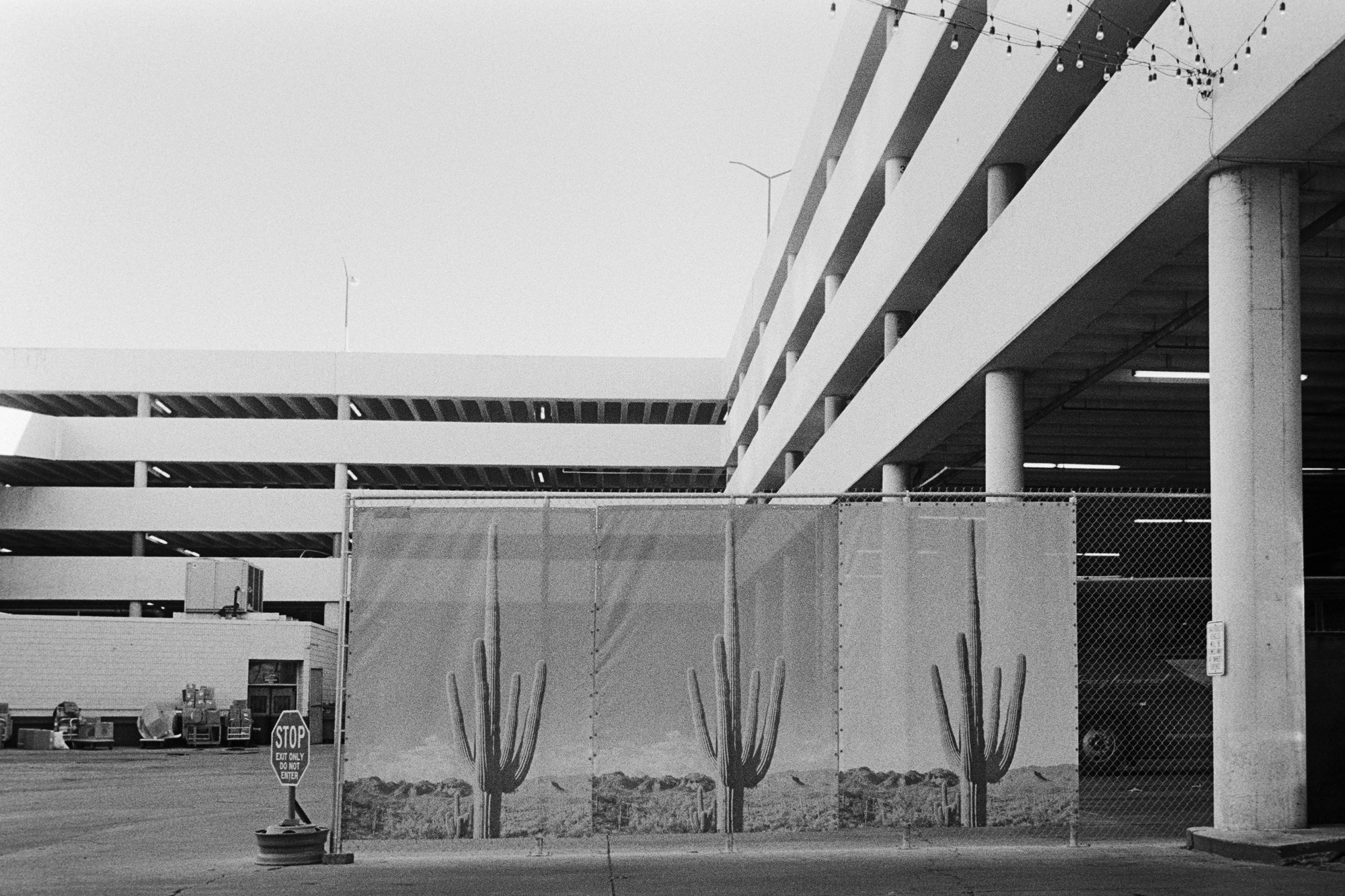

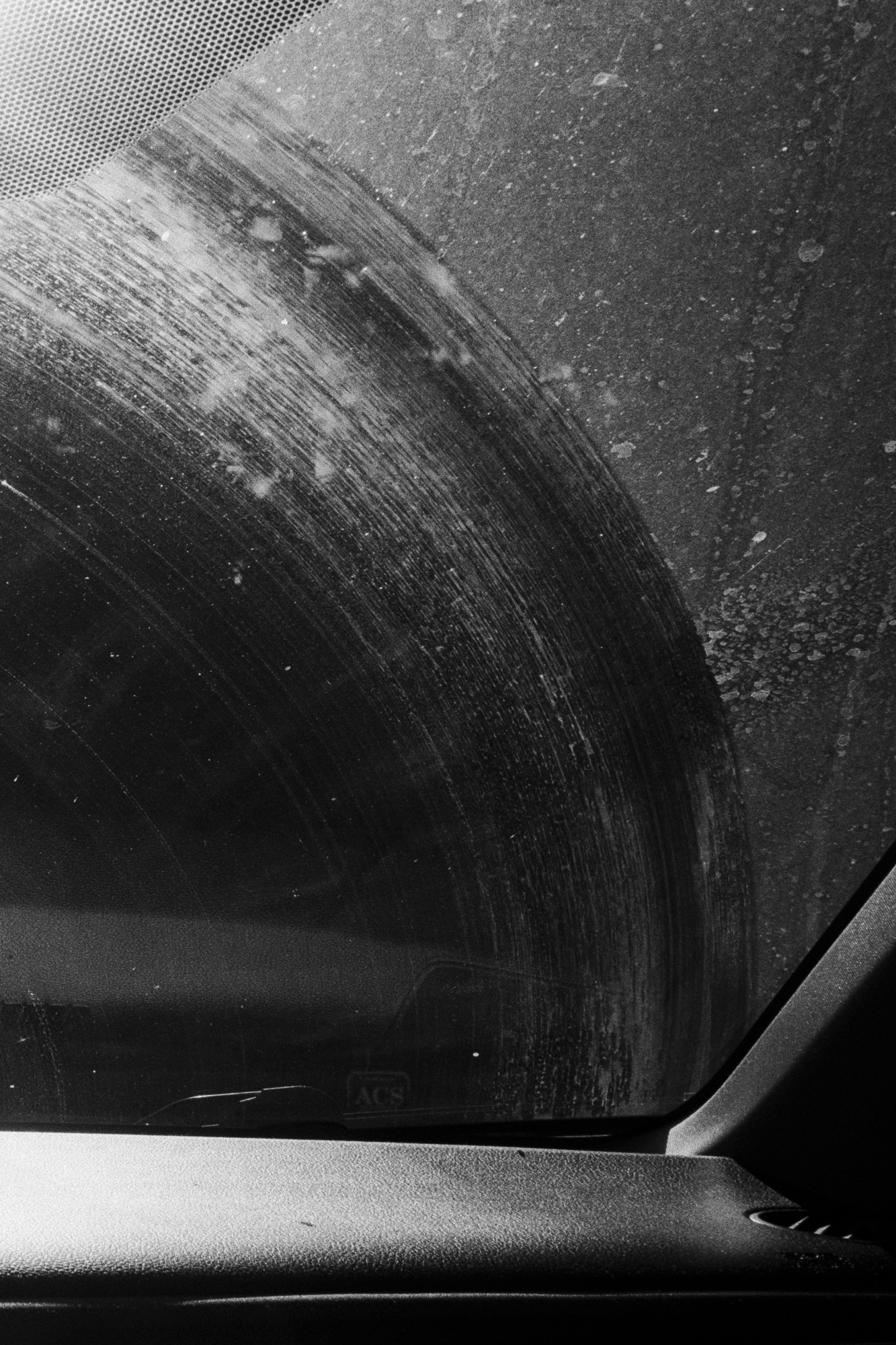

Lately I have been crisscrossing the United States as I move from one coast to the other. During these trips I’ve been using my 35mm camera with black-and-white film to document America, and these are the images I’m using to illustrate this post (and which I plan to make into a limited edition book from sometime in 2019, once I finish developing and editing all the film I’ve shot).

The series, which I’m calling The California Trail, reflect more directly on the history of Manifest Destiny and American Modernist photography than any other work I’ve made to date. This move from northeast to southwest has been consistent throughout America’s post-colonial history. It has also been a move from forests to deserts.

To a certain point, the B&W photograph I have been taking feel indulgent and sentimental. Yes, I feel guilty as I run the sink in my Los Angeles home for half-an-hour to wash my film. And I feel a bit guilty too, burning the fossil fuels required to take two road-trips from east to west (one in my wife’s car, followed by one in my car). But these trips were when I took the majority of these pictures, although a few other excursions have helped to round out the series. I also feel a tinge of guilt for another reason... sentimentally looking back at an era of photography that I have long tried to turn a blind eye to: the American modernists.

I ran away from American photography in graduate school, instead studying in the Czech Republic and becoming steeped in the parallel traditions of photography and modernism that have thrived in Central Europe. I’ve also spent a lot of time in Japan, because of my wife’s research, and there I have become really engaged in the history of postwar Japanese photography. And while these European and Asian traditions do influence this series, it is the American Modernists that I have really been thinking about, finally.

This move from east to west has placed me directly into the history of Europeans movement across America in a very tangible way. As I drove across the country, looking at all the other evidence of this movement, all the scars across the landscape, I often found myself thinking about a computer game I used to play called The Oregon Trail. Though I have seen a lot of America before this move, The Oregon Trail and its simple early computer graphics kept coming to mind: a wagon drawn by oxen across an ever-changing landscape. As I saw an iconic scene in front of my eyes, I’d think back to the tableaus depicted in these early computer graphics. And how the game also tried to portray the hardships faced by the pioneers via text descriptions (i.e. “You have died of [dysentery, cholera, typhoid, diphtheria or measles]”).

My initial choice to use 35mm film to document my road trips was practical: if I took just one roll of film a day during these drives, it would be a constraint that would limit my obsessive photographic impulses. Having only thirty-six frames per day would also mean that my photographic addiction wouldn’t drive my wife crazy during our road-trip, constantly stopping the car to get the right shot. In fact, many times I wouldn’t even stop the car, instead shooting from the moving vehicle in hopes of both finding unexpected compositional solutions as well as limiting my OCD large-format oriented photographic mind from trying to take too much control.

I didn’t have any serious intentions at the beginning of the road trip, but by the time we got to Montana I was already scrambling to find more film, as I had certainly gone over my one-roll-a-day limit! Though they’d started as impulsive documents, my ideas for why I was making these photographs kept growing as I was becoming very interested in the challenge of trying to make “good” and “fresh” photographs of these sites that had been photographed so many times before by so many great photographers.

The last time I drove across the country was 15-years-ago, and the only camera I had was a large-format camera. I was thinking about Bernd and Hilla Becher, Hiroshi Sugimoto, and Pavel Baňka as I photographed the urban and community gardens. On this more recent trip, with my 35mm camera at the Grand Tetons, or at hotels in small towns across the country, I couldn’t help but think of Robert Frank, Robert Adams, Ansel Adams, Paul Strand and Lee Friedlander.

So, let’s just go over the routes I took... Trip one (with wife and three-year-old daughter): Washington DC to Cleveland, OH to Chicago, IL to Minneapolis, MN to Bismarck, ND to Miles City, MT to Yellowstone National Park, WY to Grand Tetons National Park, WY to Salt Lake City, UT to Zion National Park, UT to Las Vegas, NV to Los Angeles, CA. Trip two (partially with my father): Washington DC to Cleveland, OH to Nashville, TN to Hot Springs National Park, AR to Dallas, TX to Guadelupe Mountains National Park, TX to Albuquerque, NM to Grand Canyon National Park, AZ to Los Angeles, CA. That’s over 100 hours and 7000 miles of driving through 25 states. And I’ve picked up five more states since then!

You won’t be shocked to hear that I noticed the landscape change as I went from east to west and north to south. Nor that what those early travelers like Lewis and Clark and the pioneers on the Oregon Trail had seen, those wide open and natural spaces, are now in quite a different state. The New Topographics photographers certainly showed us as much! Where there once were deserts, there are now oil derricks or huge pivot agriculture arms watering fresh green lettuces. The ruins of rusty infrastructure are everywhere. The bison that used to have thunderous migrations from north to south across the plains are now confined to a series of relatively small parks and reserves.

These wilds have been photographed, thought about, and written about by so many intelligent and thoughtful people (and yet, against all reason, a frightening percentage of the American population has not changed their opinion on this landscape since the days of Manifest Destiny and "Go West, young man, and grow up with the country." To me, this is the miraculous thought: not just to go West, but the need to grow up. To think about the complicated and messy world that we live in in a way that will preserve it for the future. To bear witness to the landscape’s current state. This landscape is interesting to reflection upon. There are many aspects of American history that I’m proud of, but also so much that needs a critical eye. This is essential in identifying problems and my own role in shaping its future. And that’s what I hope to be doing in this series of photographs.

But as I reflect on living in a desert on the West Coast, my mind has drifted more and more to the sea. And so, for my next post, I’ll be writing about another new project of mine called Full Fathom Five.