Gabriela Bulisova & Mark Isaac

In the middle of Lake Baikal is a remote archipelago called the Ushkanii Islands, including Big Ushkan Island, and three smaller islands, Tiny, Round and Long. These secluded and rugged isles are primarily known as the site of a rookery.

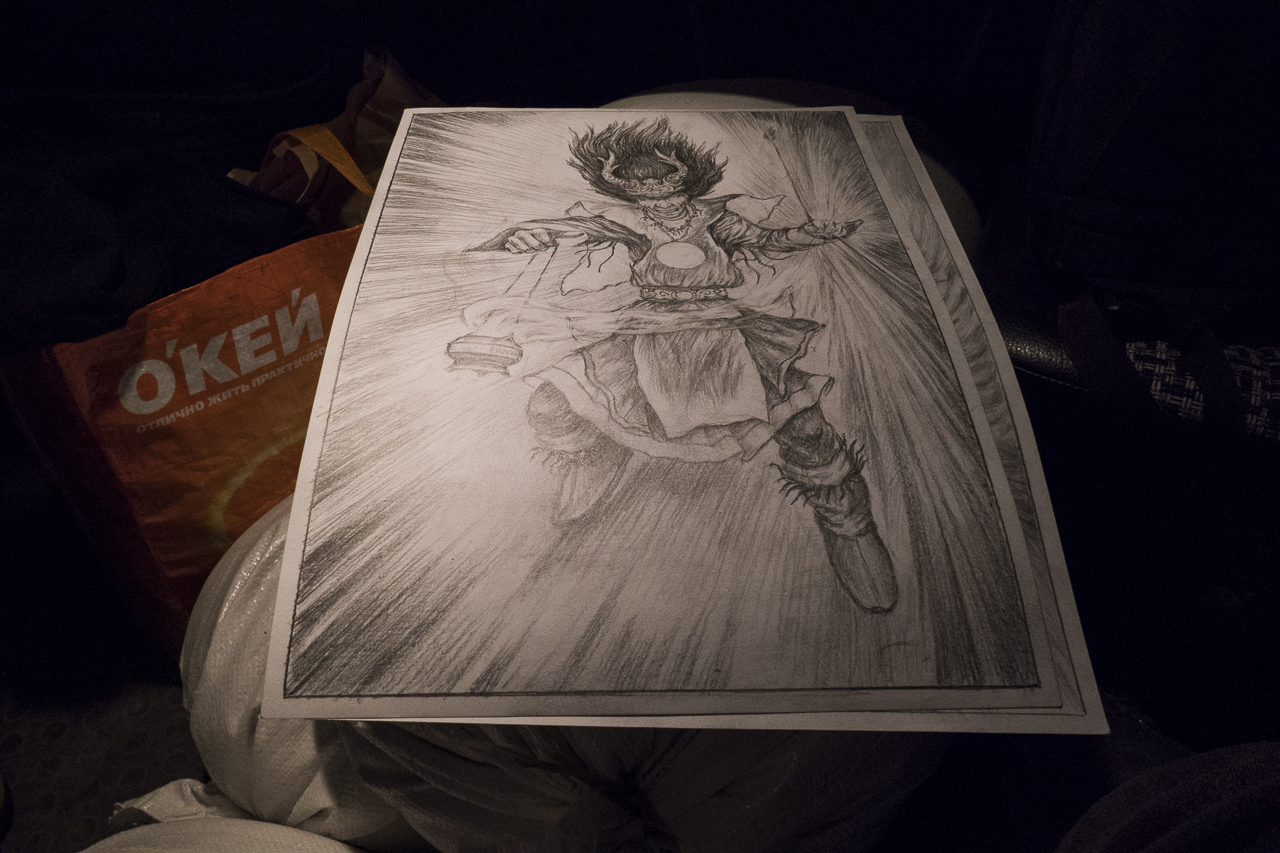

Can’t remember what a “rookery” is? Neither could we. Dictionary.com defines it as “a breeding place or colony of gregarious birds or animals, as penguins and seals.” The Ushkanii Islands are the mating spot of the world’s only entirely freshwater seal, or nerpa, the exceptionally cute mammal that is at the top of Baikal’s food chain.

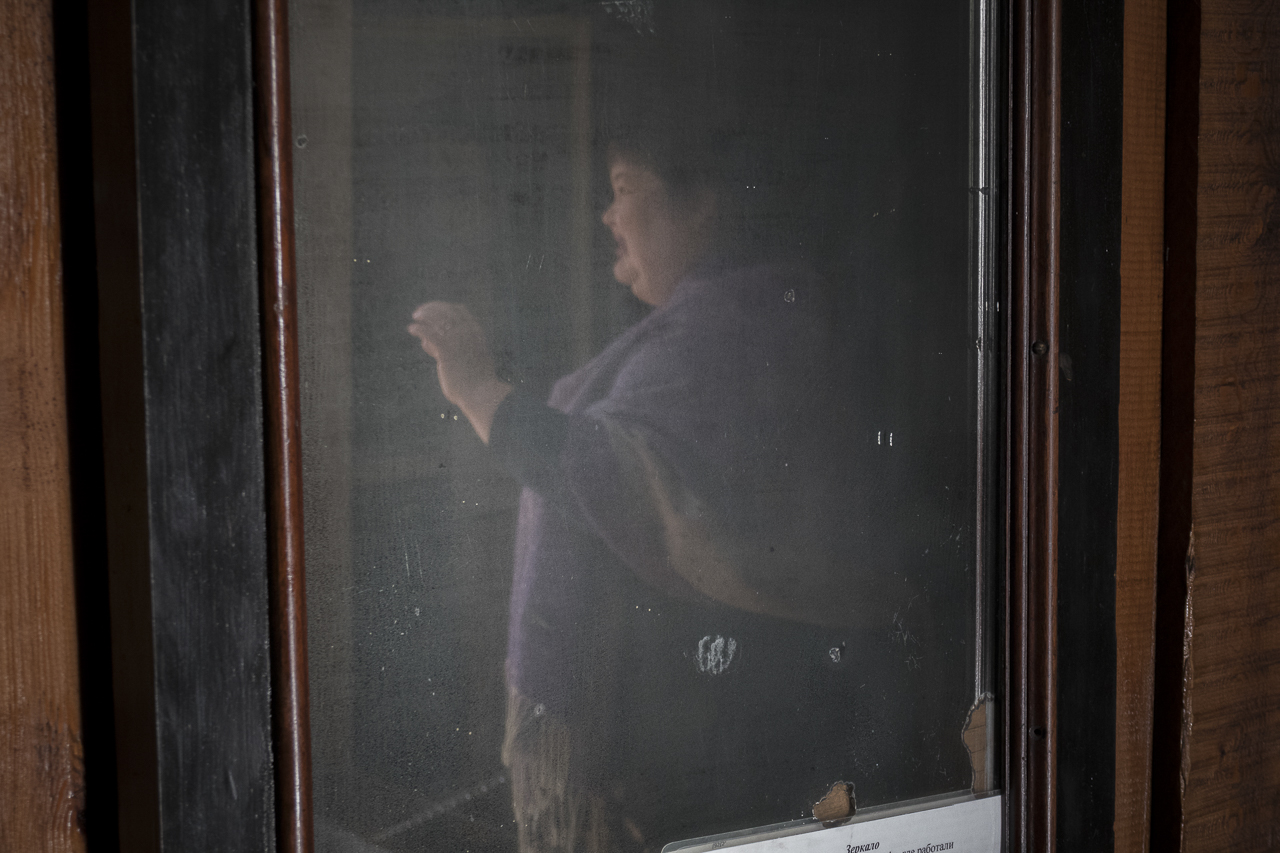

A few days ago, we had the unique opportunity to embed with a group of scientists from the Baikal Museum. The Museum operates a number of live cameras that let you peer into Baikal’s depths, scan its shoreline, and most impressive of all, view the summer rookery of the nerpas. But one of their cameras on the Ushkanii Islands was disabled, and they planned an expedition to repair it.

Outfitted with ample warm clothes, sturdy boots, flashlights, sleeping bags, dry food, and high hopes, we climbed into a truck called “Bongo” at 7:00 am. After stopping for more provisions, our driver Alexander, the Deputy Director of the Museum, stayed in touch by walkie-talkie with another group of scientists, including Director Alexander Kupchinsky, driving a truck called “Patriot.” Gradually we made our way from Irkutsk to the southern end of the Lake and started up the eastern side, entering Buryatia. By nightfall, we had reached a very modest national park hostel in Ust-Barguzin. There, amidst celebrations and libations, we attempted to sleep in a common room, some on cots and some on the floor.

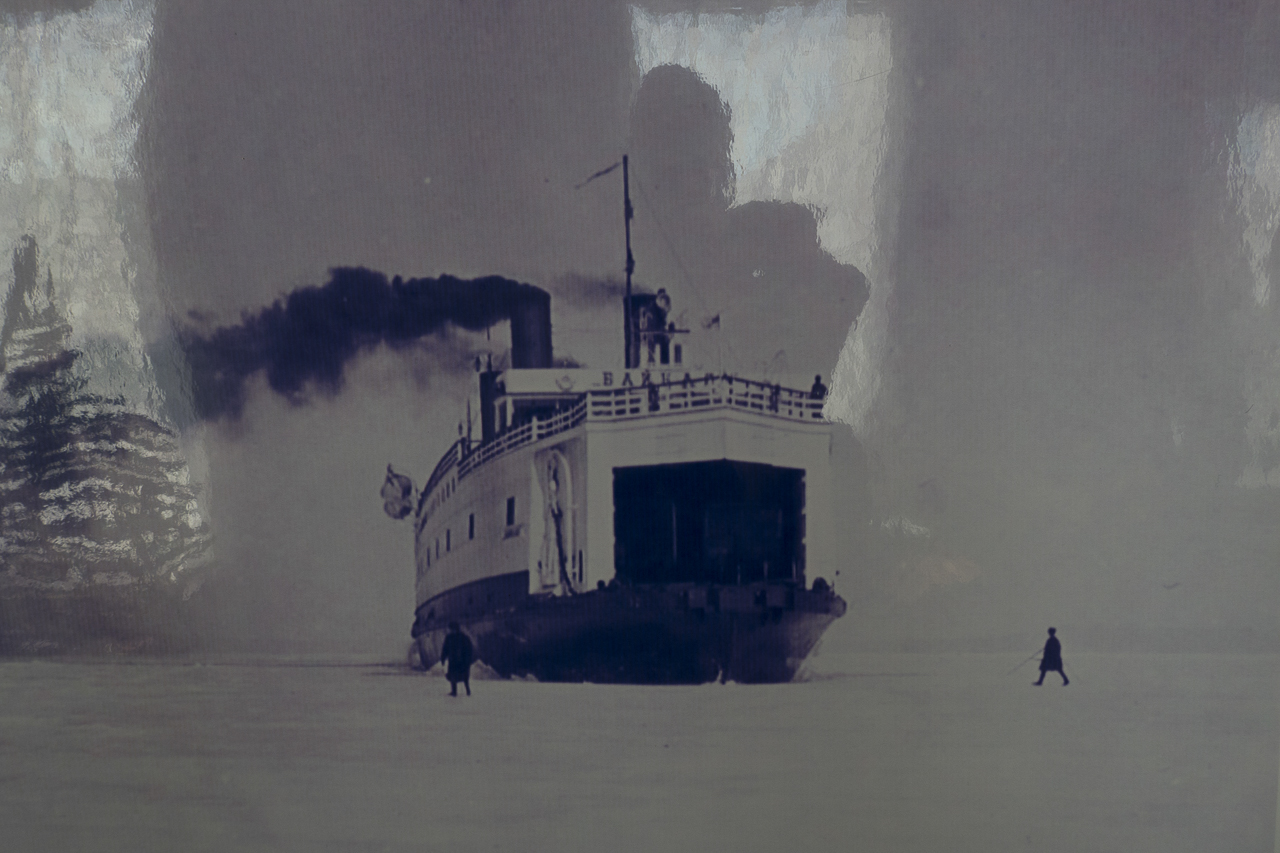

The next morning, we entered Zabaikalsky National Park on the territory of a peninsula known as the “Holy Nose.” Winding our way on dirt roads through the park, we eventually reached a set of signs with a variety of prominent warnings in Russian. Here the expedition would enter the open ice of Baikal and travel to the Ushkanii Islands.

It was only one week earlier when we first rode in a marshrutka (or minibus) on Baikal’s ice, on our way to Olkhon Island. It was quite fantastical at first because the mind can’t fully comprehend how ice safely supports an entire bus. But at Olkhon, the frozen road is marked and monitored by authorities. This time, we were sneezed out of the Holy Nose to navigate on our own.

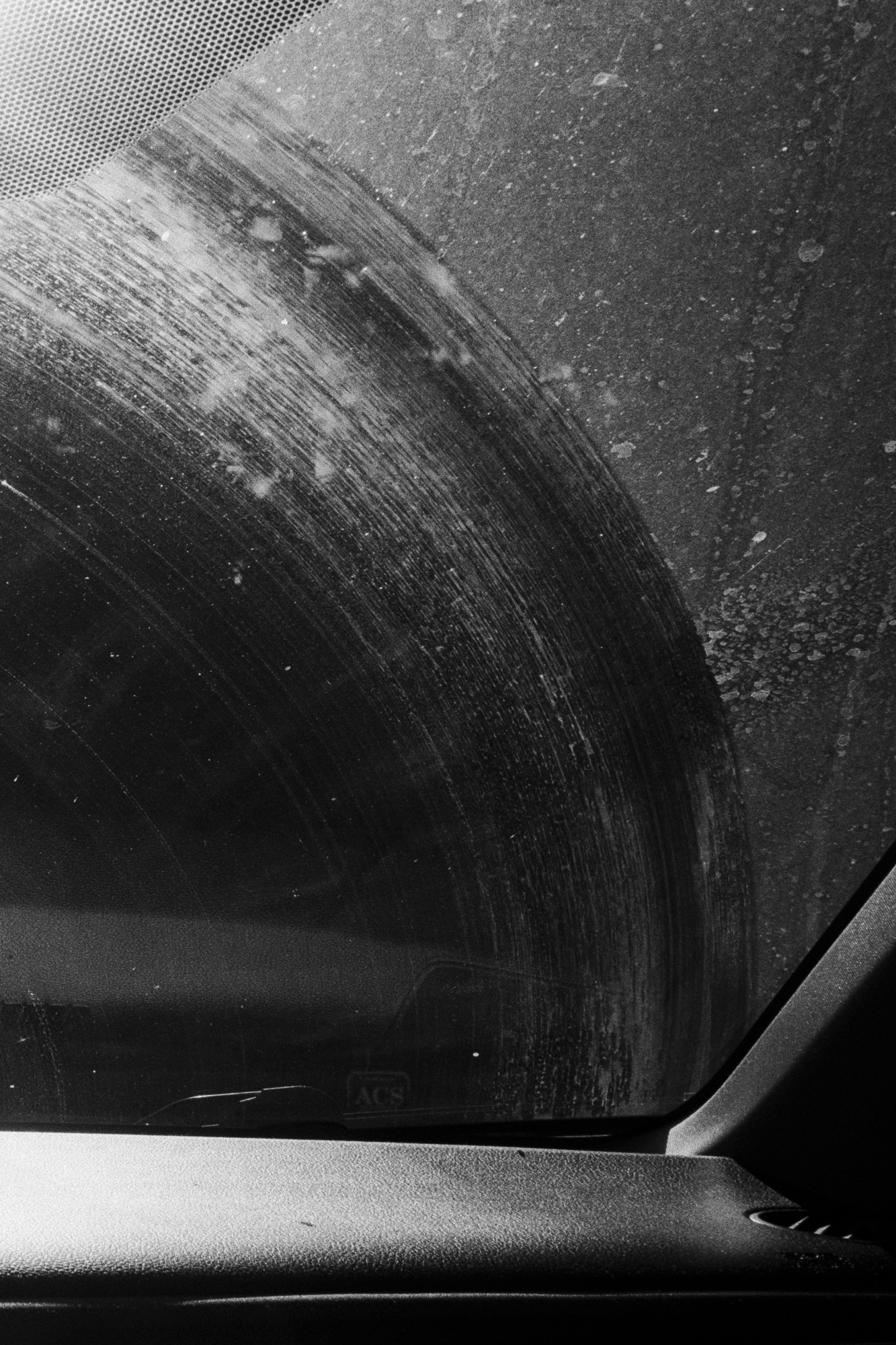

Sometimes Google can find your car on Lake Baikal.

Sometimes it can’t.

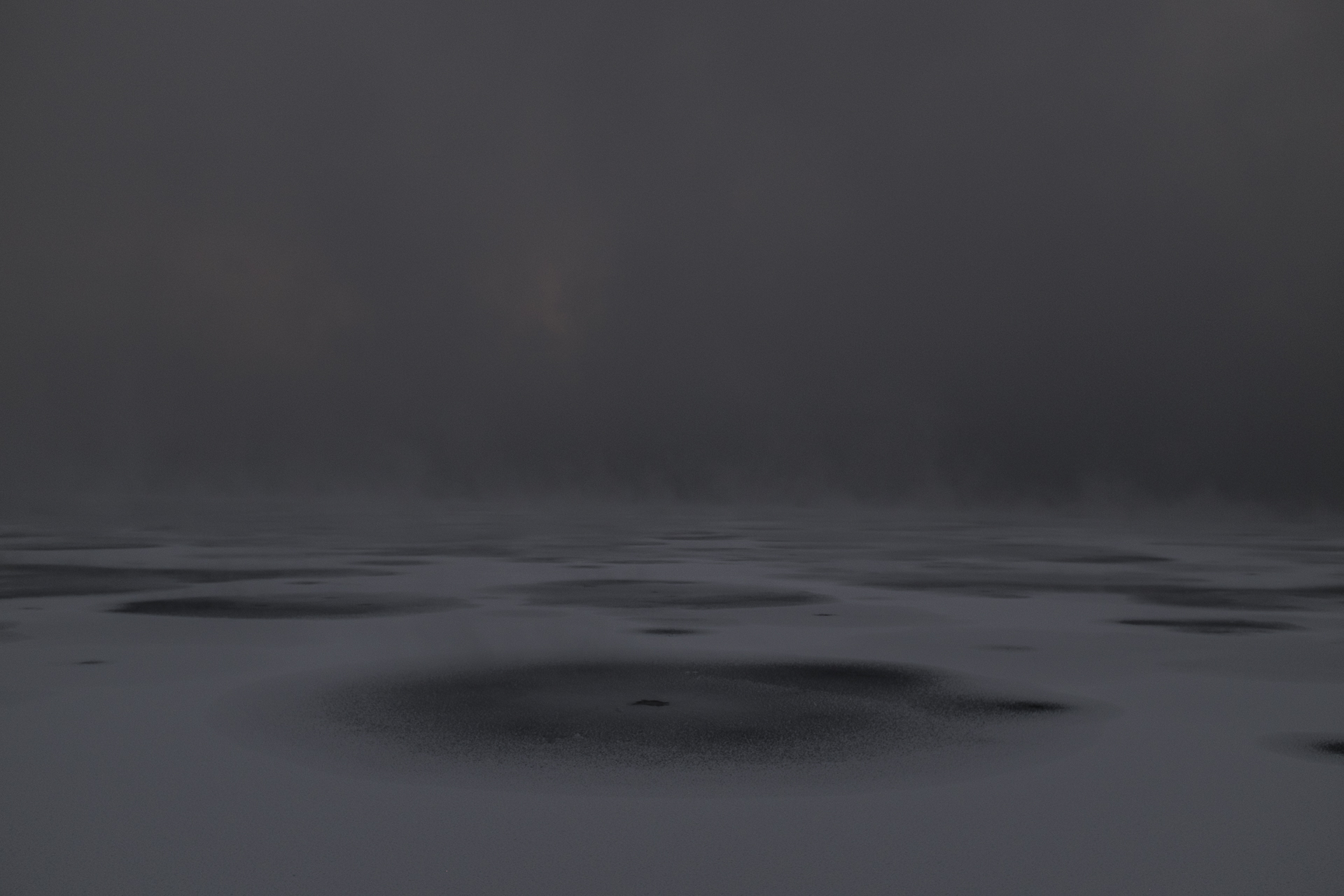

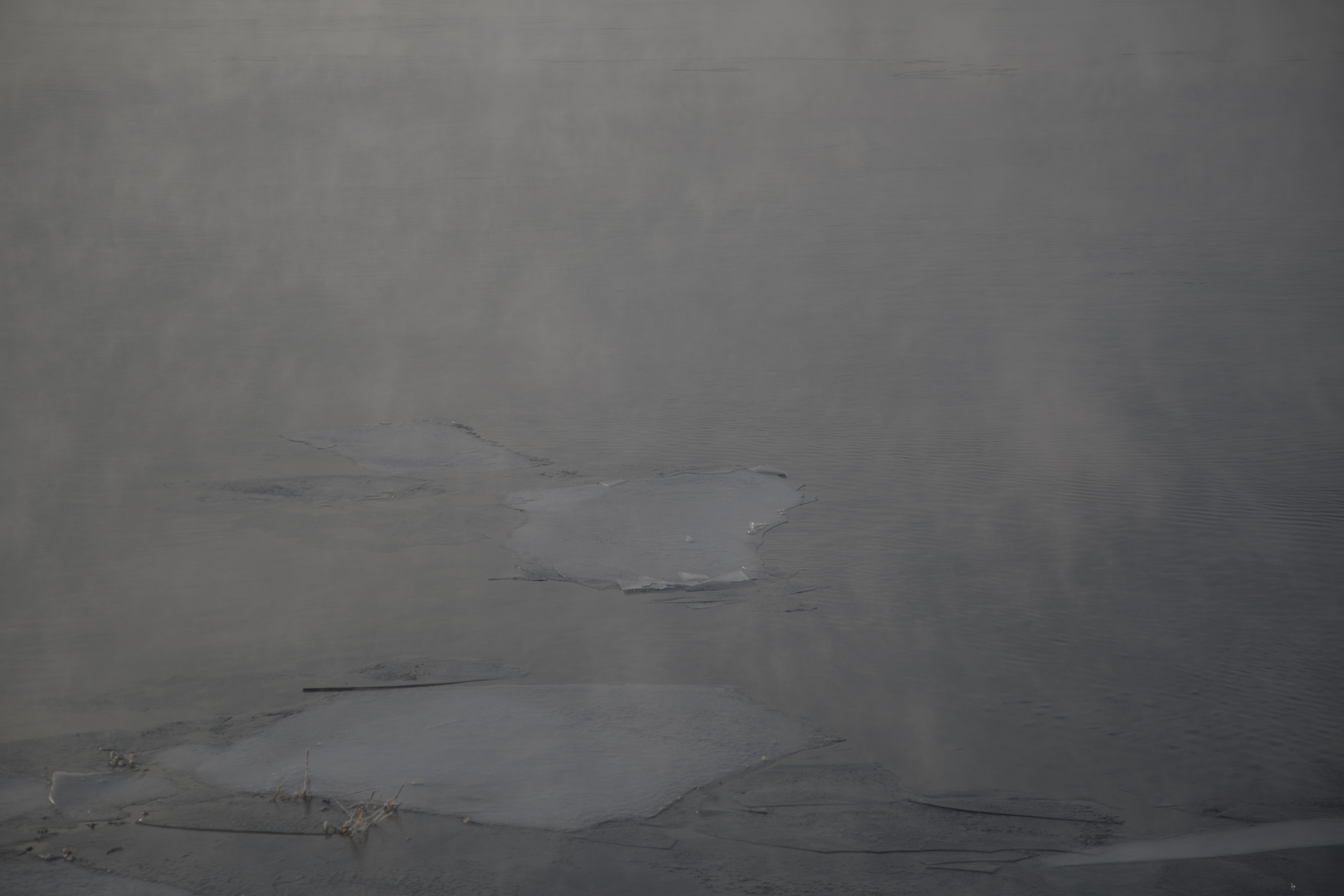

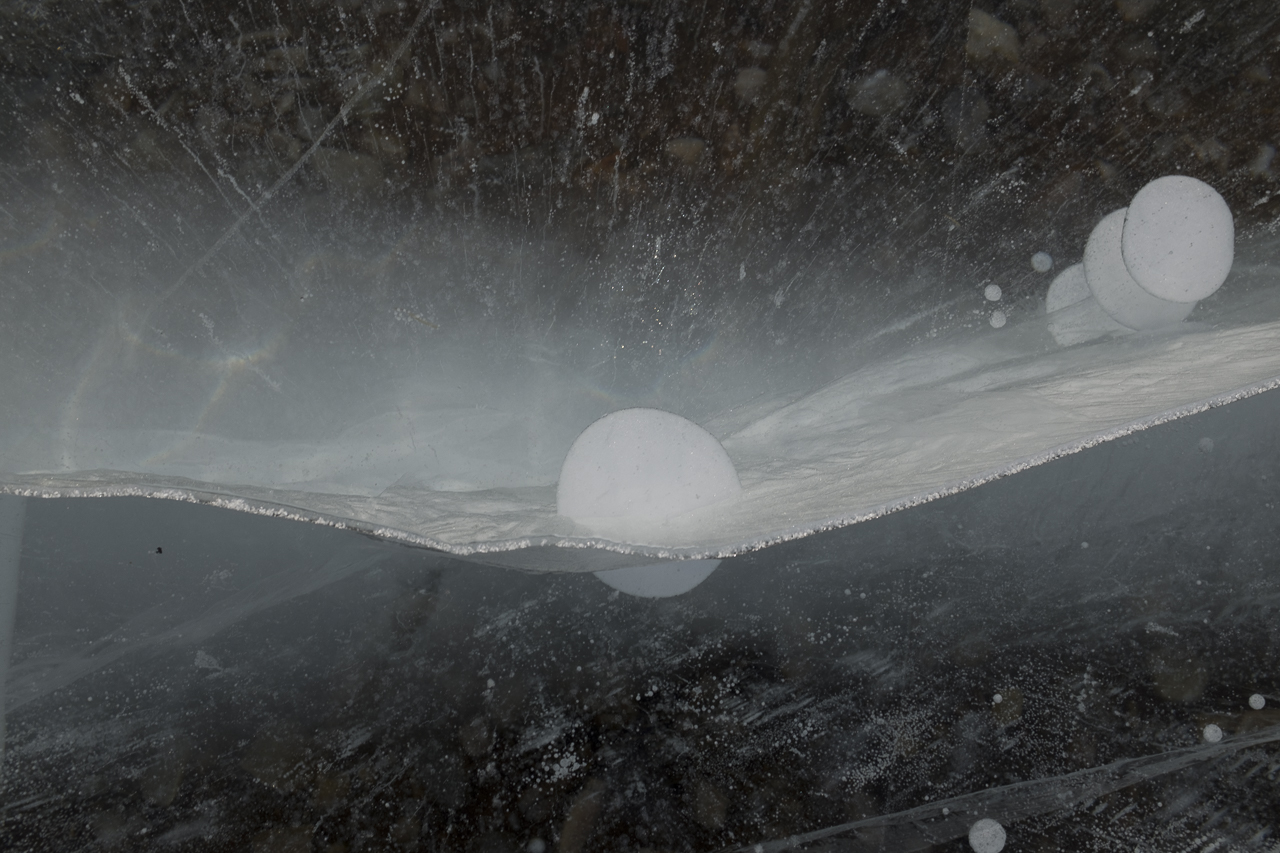

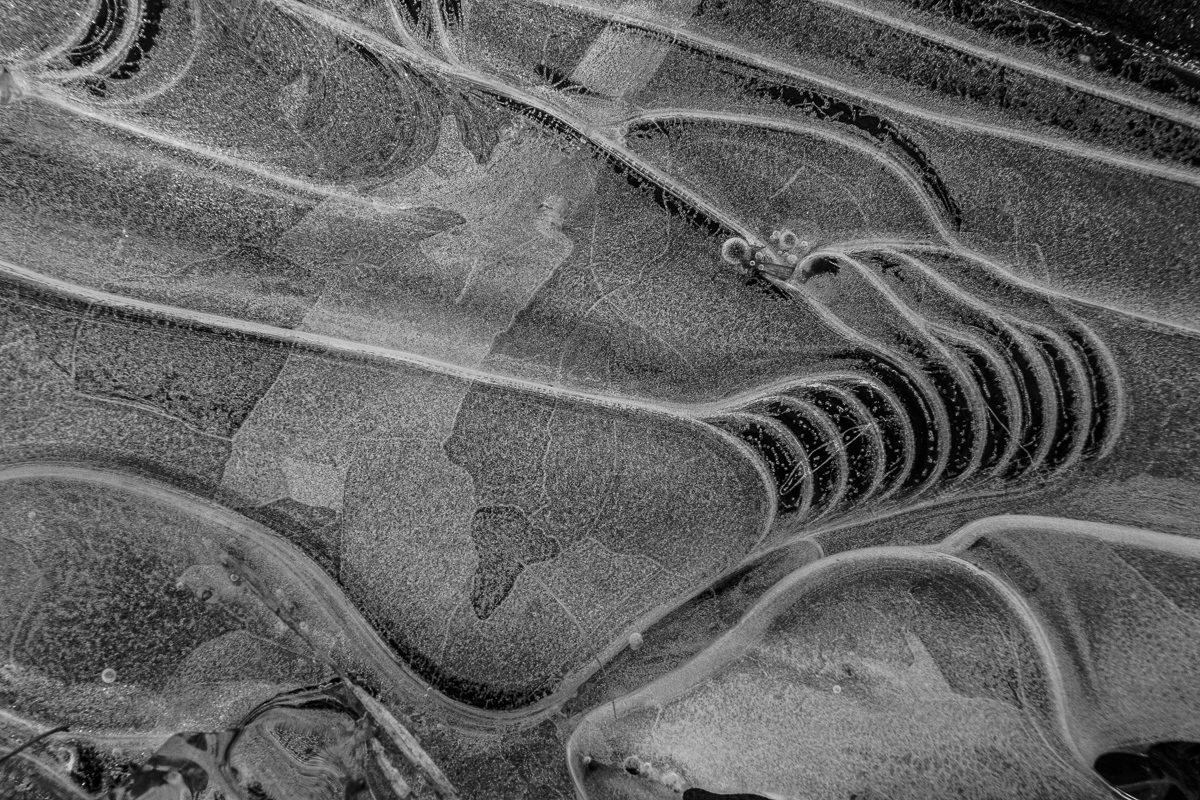

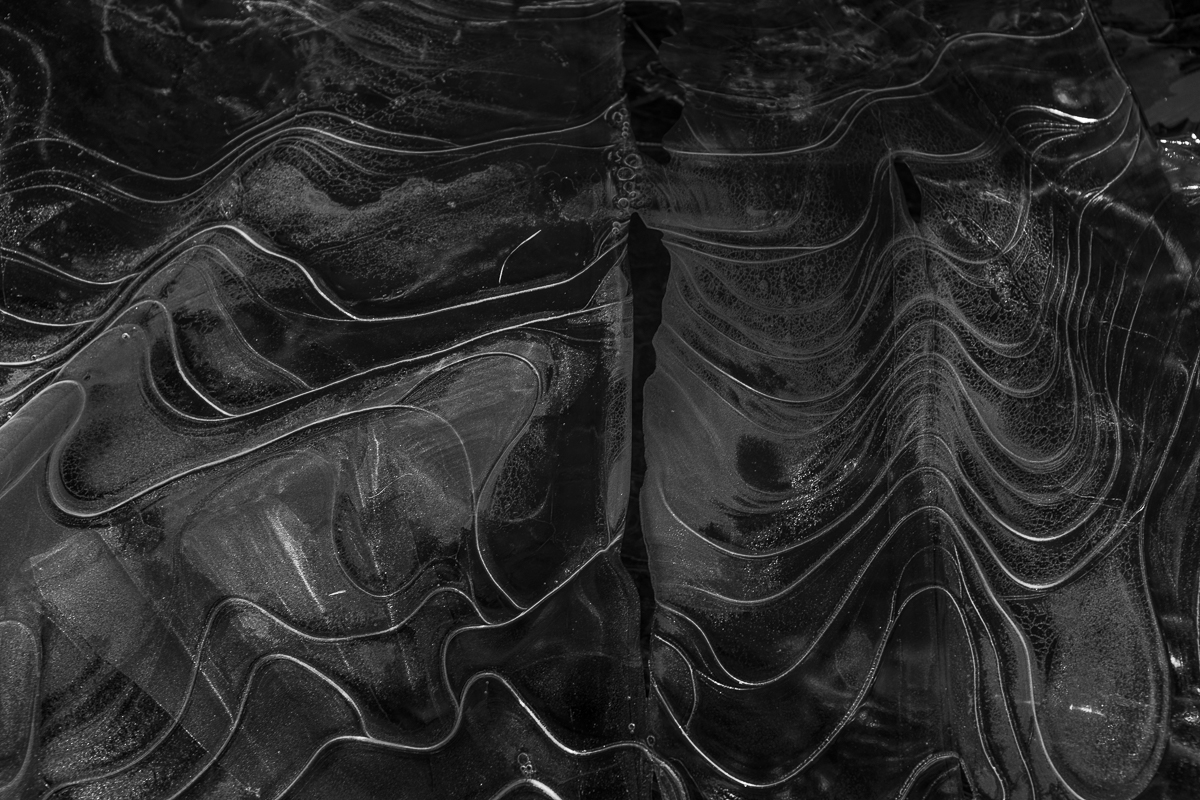

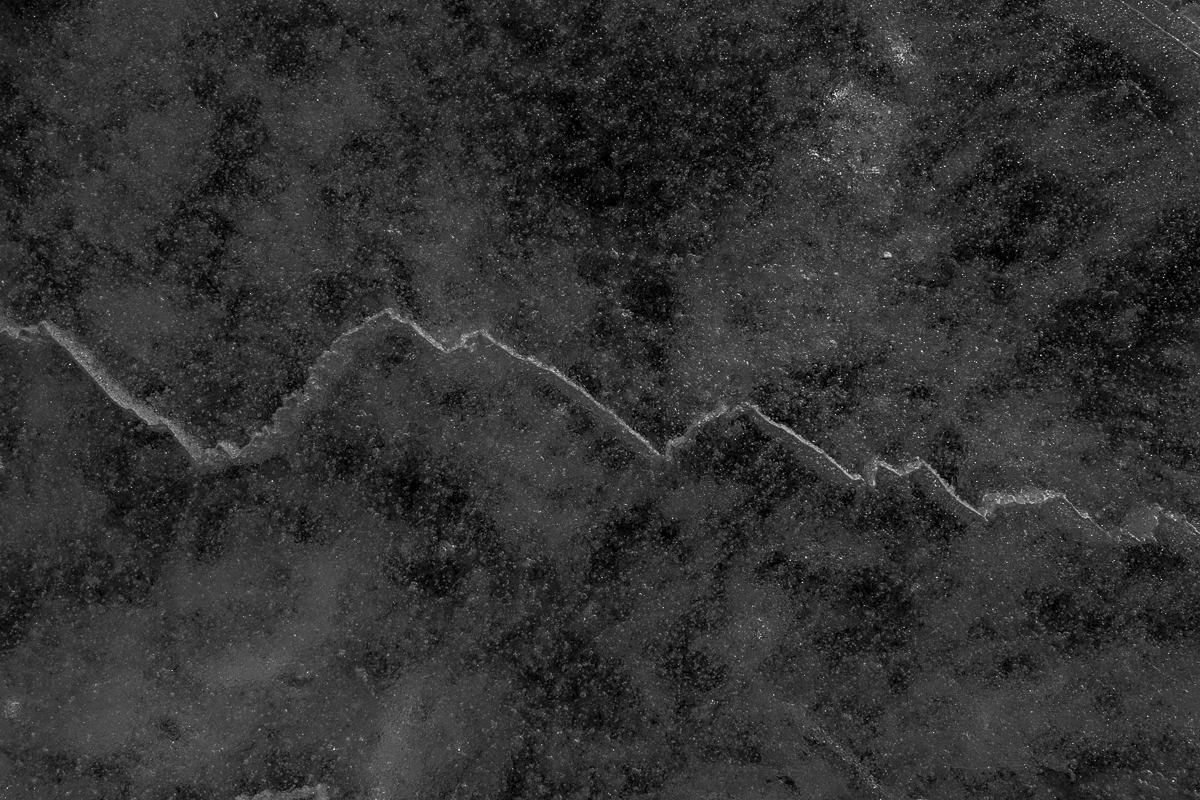

And the ice is not without perils. This year, there are a startling number of large cracks, many stretching kilometers in erratic patterns. Some have refrozen and can be crossed easily with four wheel drive. But others are “live,” meaning they are still actively piling massive, bright blue ice boulders in front of passenger vehicles, or exposing dangerous open water into which truck wheels -- or an entire truck -- could plunge.

In fact, we quickly met several obstacles of piled ice that were insurmountable, and we were forced to drive many kilometers searching for a suitable location to pass. And then we came upon open water that emphatically blocked our way forward. We waited uncertainly, wondering if the mission might need to be abandoned. But the resourceful scientists were ready. They lay long wooden boards across the lapping waters and navigated the vehicles across an improvised bridge to the other side.

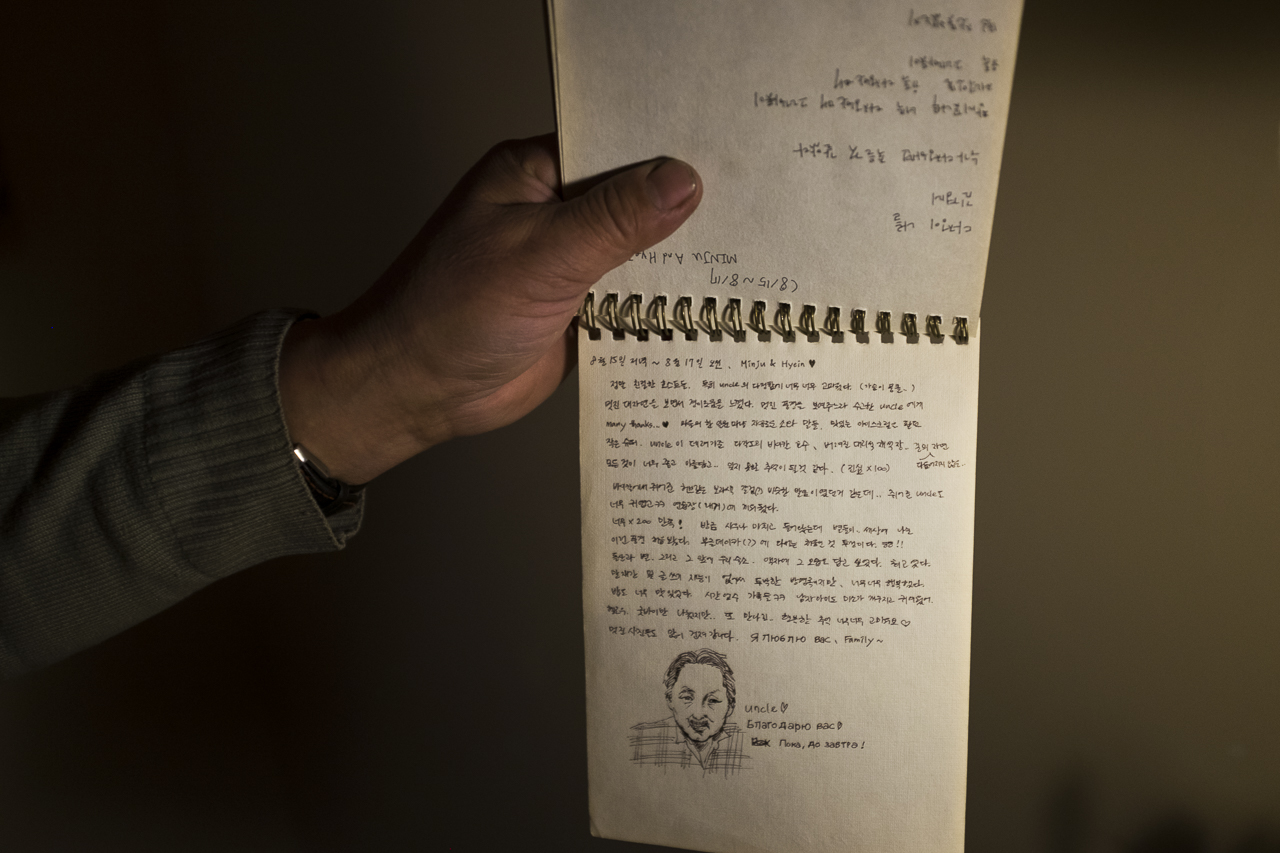

This maneuver enabled our arrival by evening to living quarters on Big Ushkan Island, hosted by Tatiana, a kind-hearted Russian women who lives year-round in this location. We warmed ourselves next to a traditional pechka (Russian stove) and feasted on simple but satisfying dishes.

In the morning, we left camp, driving a short distance in Bongo and Patriot to the base of a hill. We darted up the steep slopes, across the snow and through the forest to the peak, where the broken video camera was situated. Here, reticent Volodya quickly diagnosed the problem, and Anka, a spirited guide from the museum, descended to the trucks to retrieve a critical part.

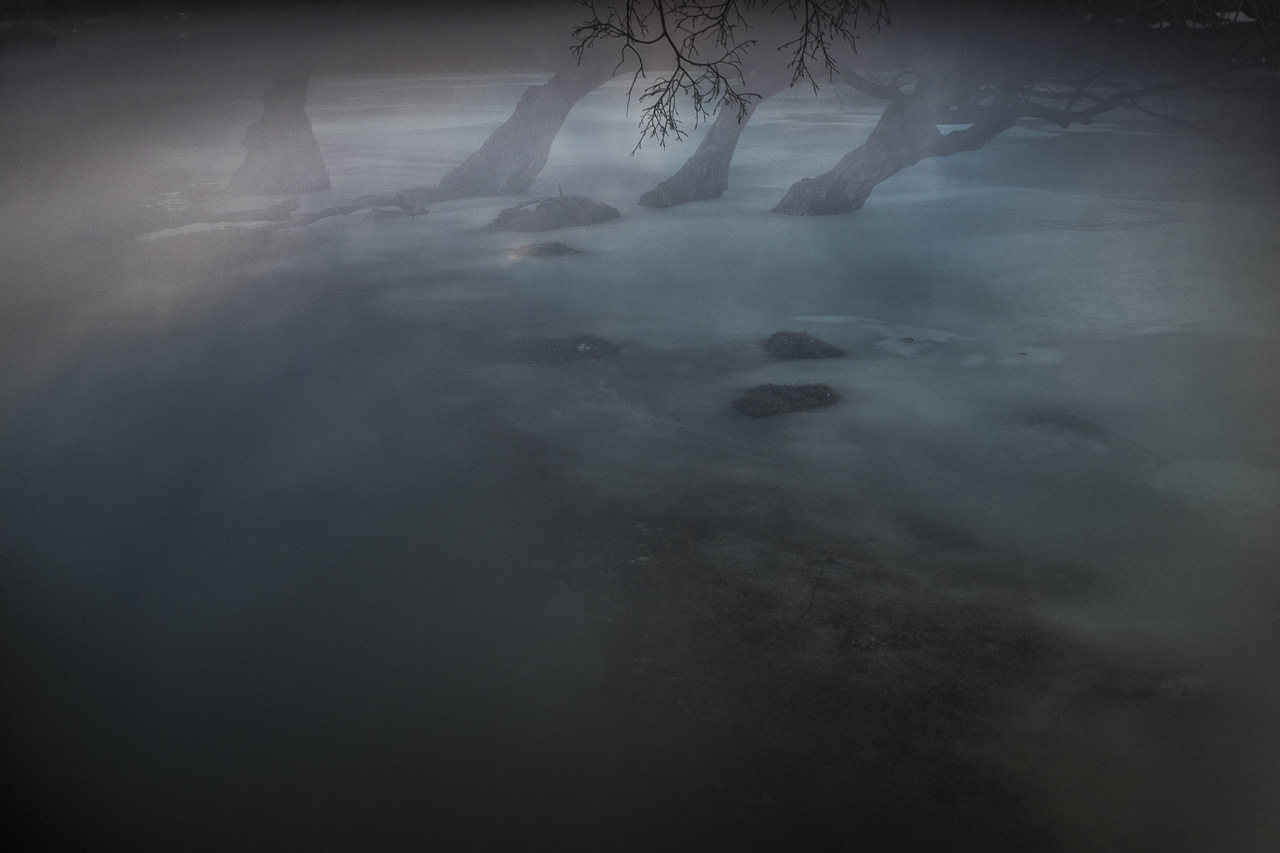

In the meantime, we savored the delicate, precious quiet that is so rare in today’s world, with only a woodpecker and the gentle wind punctuating the silence. And we stood in awe, gazing from the heights at miraculous vistas. The unending expanse of ice, interrupted only by massive cracks. The majestic mountains of the Holy Nose, rising in perfect triangles that betray the story of their cataclysmic, seismic origins. The smaller Ushkanii Islands, their thick larch forests blurred by a nebulous fog. They are all incomparable to any other place we know.

Repairs were accomplished quickly, and after one more night at the camp, we found ourselves departing this Shangri-la -- and again searching for ways across Baikal’s serpentine crystal blockades. Tatiana attributed the large number of cracks to the sudden temperature change in February. In the beginning of the month, the Baikal region was still experiencing “moroz,” or the severe frost of -20 to -40 Celsius. But by the end of the month, temperatures had soared to between +5 and -15 Celsius.

Of course, no one event can be attributed specifically to climate change. Instead, it is the trends over time that establish scientific validity. But back in Irkutsk, Daria Bedulina, a scientist at Irkutsk State University’s Institute of Biology, wrote a telling post on Instagram. “The planet heats unevenly,” she wrote. “On average, since the beginning of the 20th century, the temperature on the Earth’s surface has increased by 1 degree, but in polar regions and in Siberia, this is happening two to three times faster.

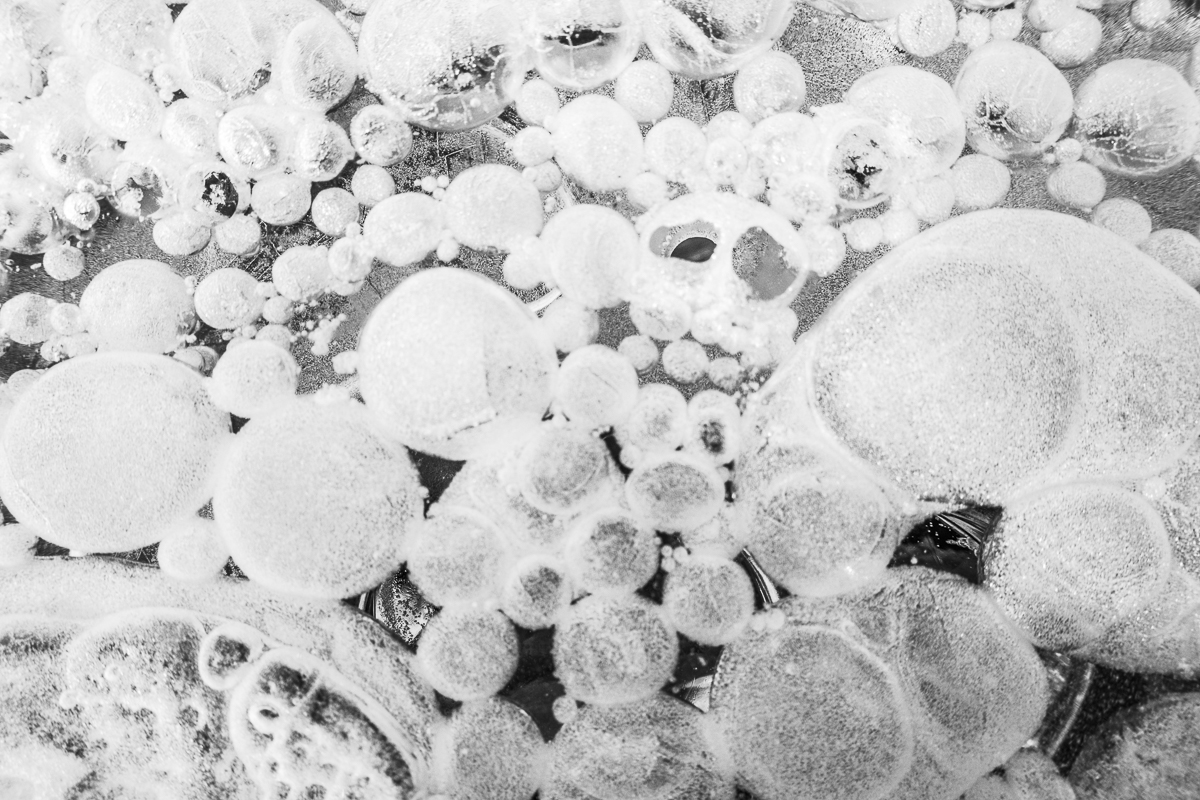

“Ice is very important for our lake, and it is gradually going away,” she continued. In 50 years, the duration of the ice has reduced by 14 days. And this did not happen without any impact for cold-loving native species. Their numbers began to decline sharply, and they were replaced by heat-loving non-native species that are plentiful in other lakes.”

Sadly, we did not see any nerpas at the Ushkanii Islands. At this time of year, they are still hiding under the ice, and will emerge later in the season. You, too, will be able to view them on the newly repaired live web cam, located on the Baikal’s Museum’s website. (See especially the top two web cams on the left side of the screen.)

But nerpas, like other native species, rely heavily on the ice for their survival. It is under the ice that new pups are raised, and if pups don’t completely molt while the ice is still standing, they will become ill or suffer attacks from birds. Also, the nerpas eat fish that, in turn, feed on smaller native species that are negatively impacted by rapidly rising temperatures. It is an unfortunate fact that the entire ecosystem of Baikal is at risk if there are drastic changes in the ice cover.

Daria Bedulina’s post was immediately disputed by climate skeptics claiming that warming is cyclical and not a serious issue for the Lake. But she defended the findings of Russian and international scientists, and she called attention to simple steps we can all take to reduce negative outcomes.

As we crossed huge cracks in Lake Baikal’s ice, we worried about our own safety. But it is the safety of Lake Baikal that should be foremost in our minds. We must not let fissures in society turn us away from incontrovertible evidence. Nor can we let Baikal’s ecosystem be irreparably fractured.

A Buryat legend suggests that Lake Baikal was created after an epic earthquake when fire sprang out of the earth and local people chanted, “Bai, gal!,” or “Fire, stop!” in the Buryat language. Now, the Lake is threatened by a new type of fire -- temperatures that are rising more rapidly than scientists expected.

This time, an inferno did not erupt from the earth in a sudden convulsion. Instead, accumulating heat creeps and glides and insinuates itself under Baikal’s precious ice. But a cry of “Fire, stop!” is just as apt today as it was at the moment Baikal was born.