By Gabriela Bulisova and Mark Isaac

If the goal is to get to Lake Baikal quickly, Listvyanka makes it easy. Sitting at the source of the Angara River, Baikal’s only outlet, Listvyanka is a mere one hour marshrutka (minibus) ride from Irkutsk. It also has a reputation as the most commercial and touristy of all lakeside destinations, drawing a surfeit of visitors twice a year. In the summer, the warm weather inspires swimming, boating, and hiking. In the winter, skiing draws the crowds.

In late autumn, though, tourists are more of an oddity. We were the only ones registered at the Gavan Baikala (Baikal Harbor) Hotel, and we selected a choice room with views through a deep canyon toward the immensity of the Lake in the distance.

One reason people are scarce in fall is the capricious weather. When we arrived, it was sunlit and undeniably warm. In the evening temperatures plummeted, and we woke to a delicate snow powdering the landscape. Throughout the next day, faint sun alternated with blasts of wind and drizzle. It was every season in one.

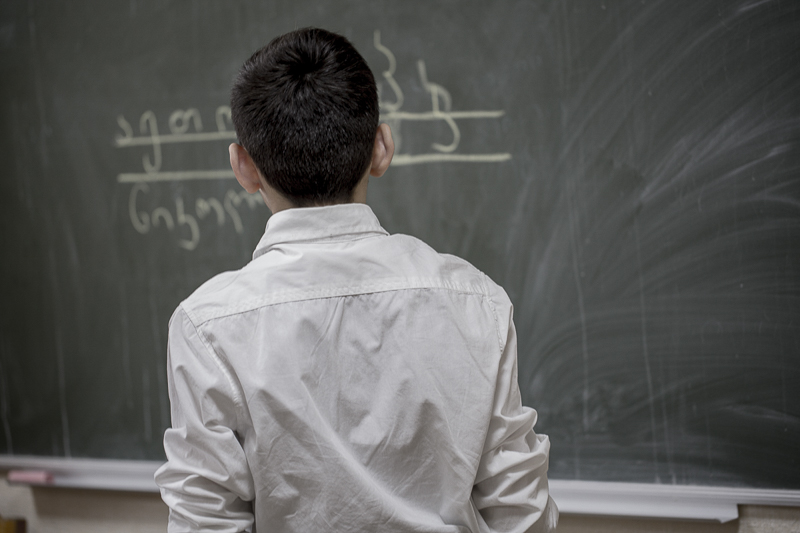

Despite catering to tourists, Listvyanka is a small town with cows wandering its dirt roads and traditional wooden houses packed in amongst Soviet-era apartment buildings. It also has a burgeoning collection of small luxury hotels -- some legal and some that likely are not. There is a buzz about excessive construction fueled by Chinese investors, who allegedly build structures under rules for family homes and then operate them as hotels. And there is outrage over “lectures” by Chinese guides who contend (indefensibly) that Lake Baikal is historically Chinese and only in Russian hands temporarily.

The problem with the building boom is that the town has very limited sewage treatment capacity, so when tourists inundate the area, excess sewage flows directly into the Lake. While an influx of easy money is hard to resist, it may culminate in an environmental catastrophe that chokes off tourism permanently. And scientists are already raising alarms about high levels of dangerous pollutants and the mass death of native sponge populations in the waters surrounding Listvyanka.

For the moment, this tourist mecca is a strange blend of visual and emotional experiences. The collapsing concrete esplanade attracts sightseers who bound out of cars with selfie sticks to make a permanent record of their rapture in front of the Lake. The wooden houses, wandering bovines, and roadside stands offering smoked omul (the most prevalent of Baikal’s fish) present a pastoral scene. The stuffed seals, omnipresent Coca-Cola signs, and men using bullhorns to tout boat trips expose a kitschy capitalism. The construction of faux-glamorous hotels suggests a luxury that is still mostly aspirational. And often there is a rough (but photogenic) edge to the scenery, with building materials strewn about, crumbling fences, and peeling paint.

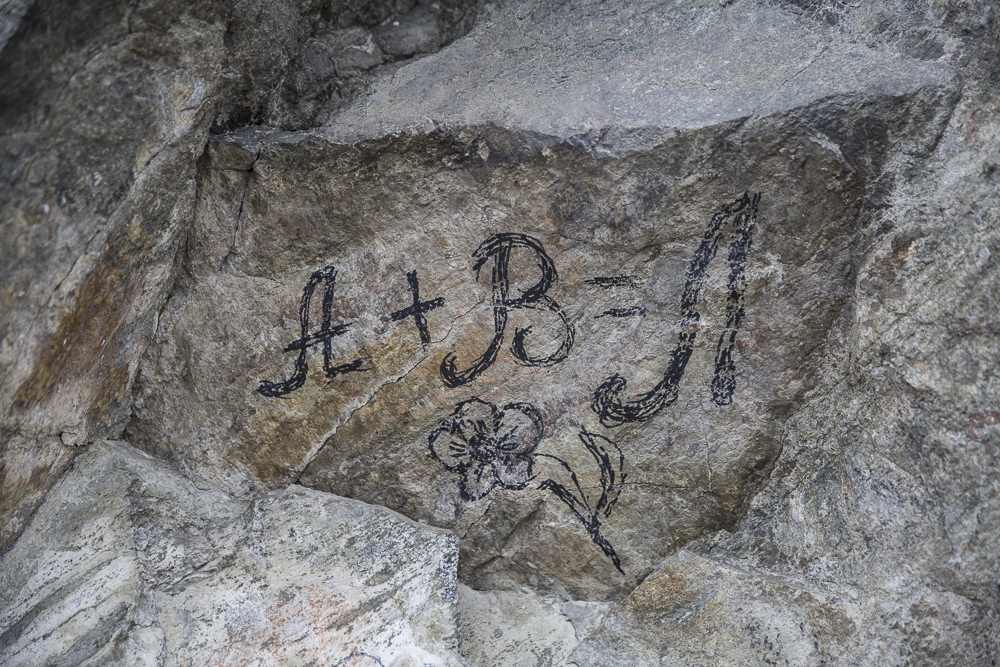

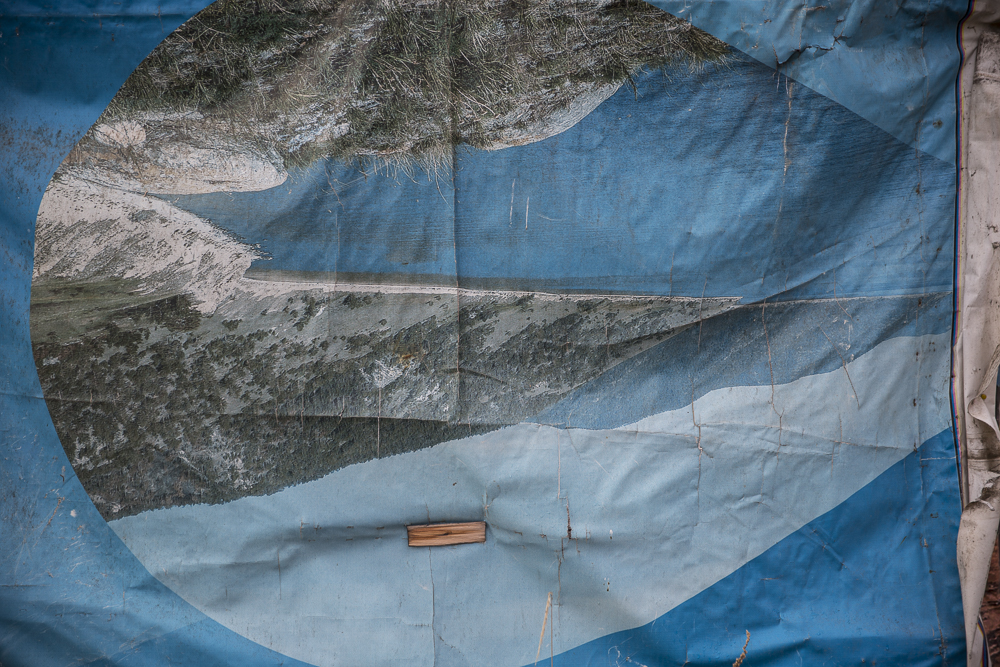

All that is juxtaposed with the sublime experience of walking out of the village to the east, in the direction of Bolshie Koty (see our blog post from that location, here). At first, grim metal lockers mar the pebbled beach. A few steps away, a landslide has deposited a torrent of boulders on the banks. Then, an ascent along the cliffside offered an astonishing perspective on the Lake’s incomprehensible vastness. Despite a dense cloud cover, a slim opening in the sky in Buryatia created a luminous white line on the Lake’s surface, a divine presence that persisted implausibly. Did it mean the gods were pleased with our visit?

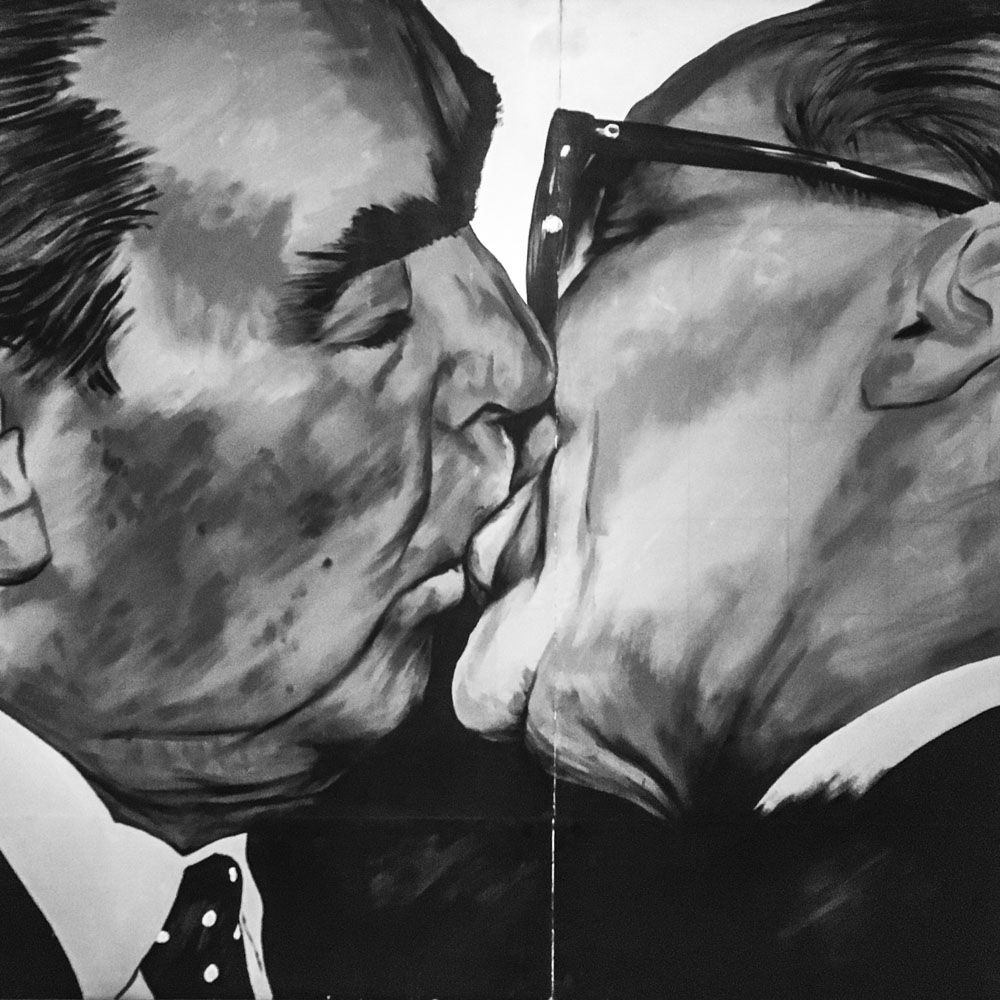

We’d like to think so, but ultimately, it’s difficult to be a visitor in Listvyanka. The town’s messages are mixed, and it is disturbing to think that in small ways, we contributed to the growing problems facing the Lake. We came to kiss Lake Baikal and tell others of its charms, but we were left to ruminate...was it a kiss goodbye?