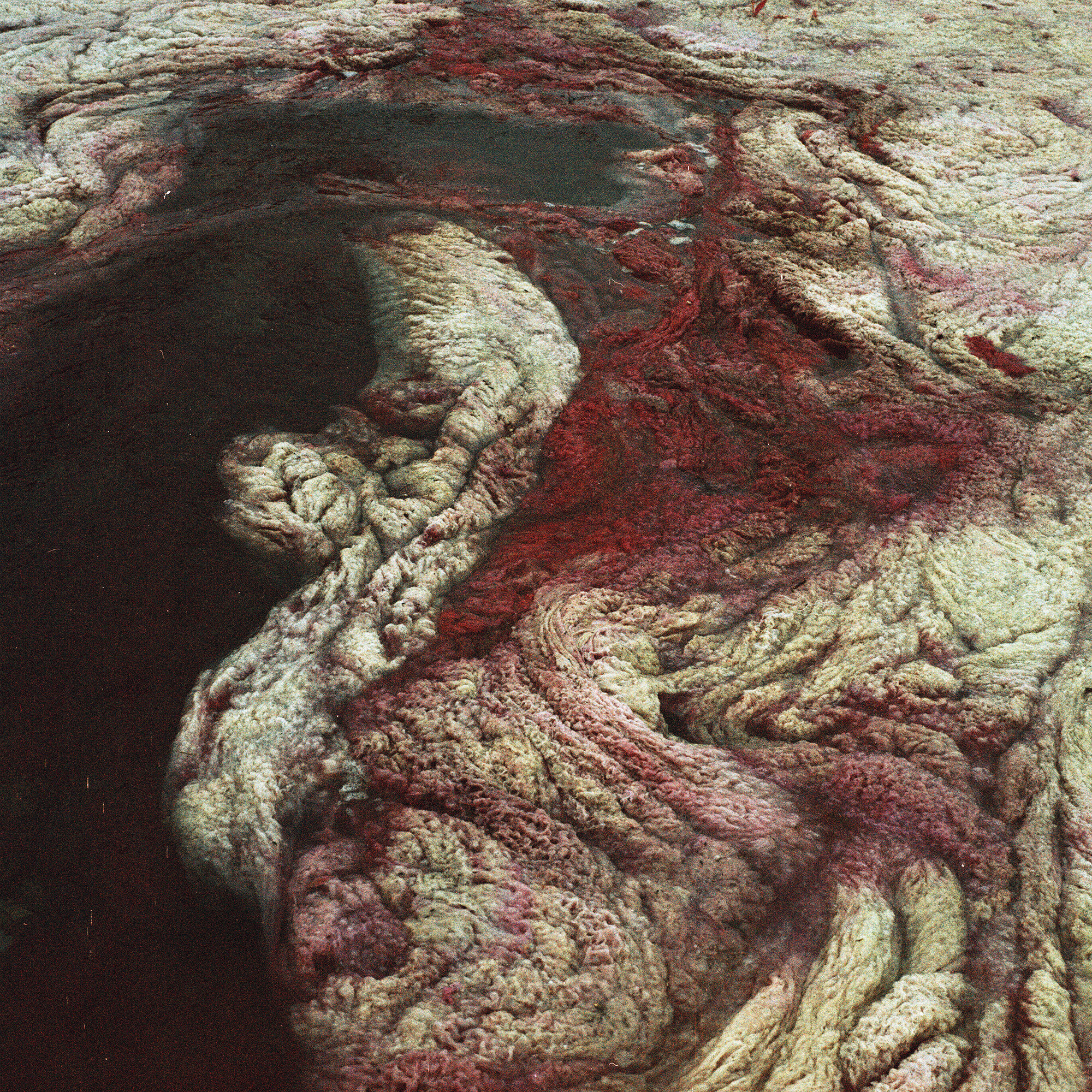

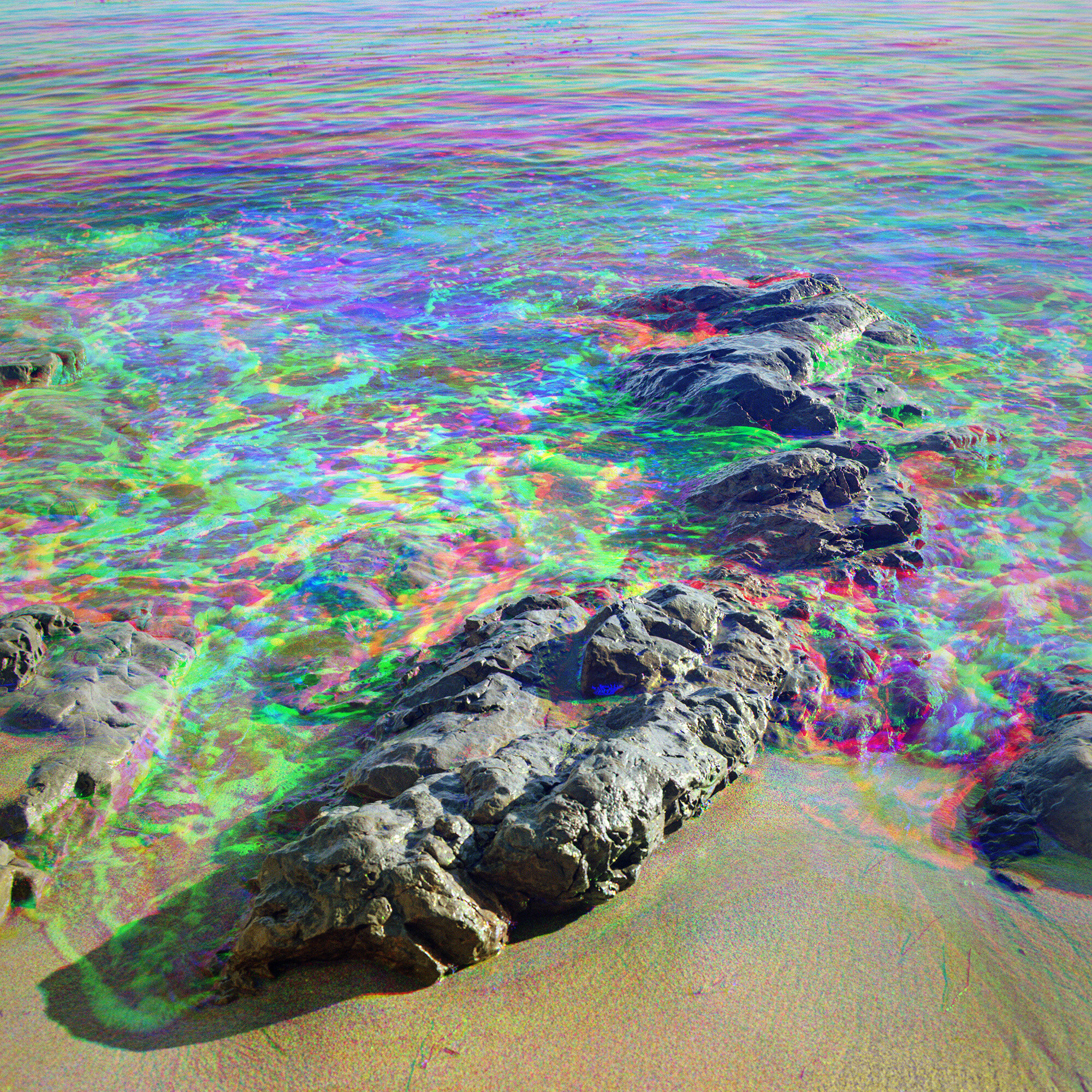

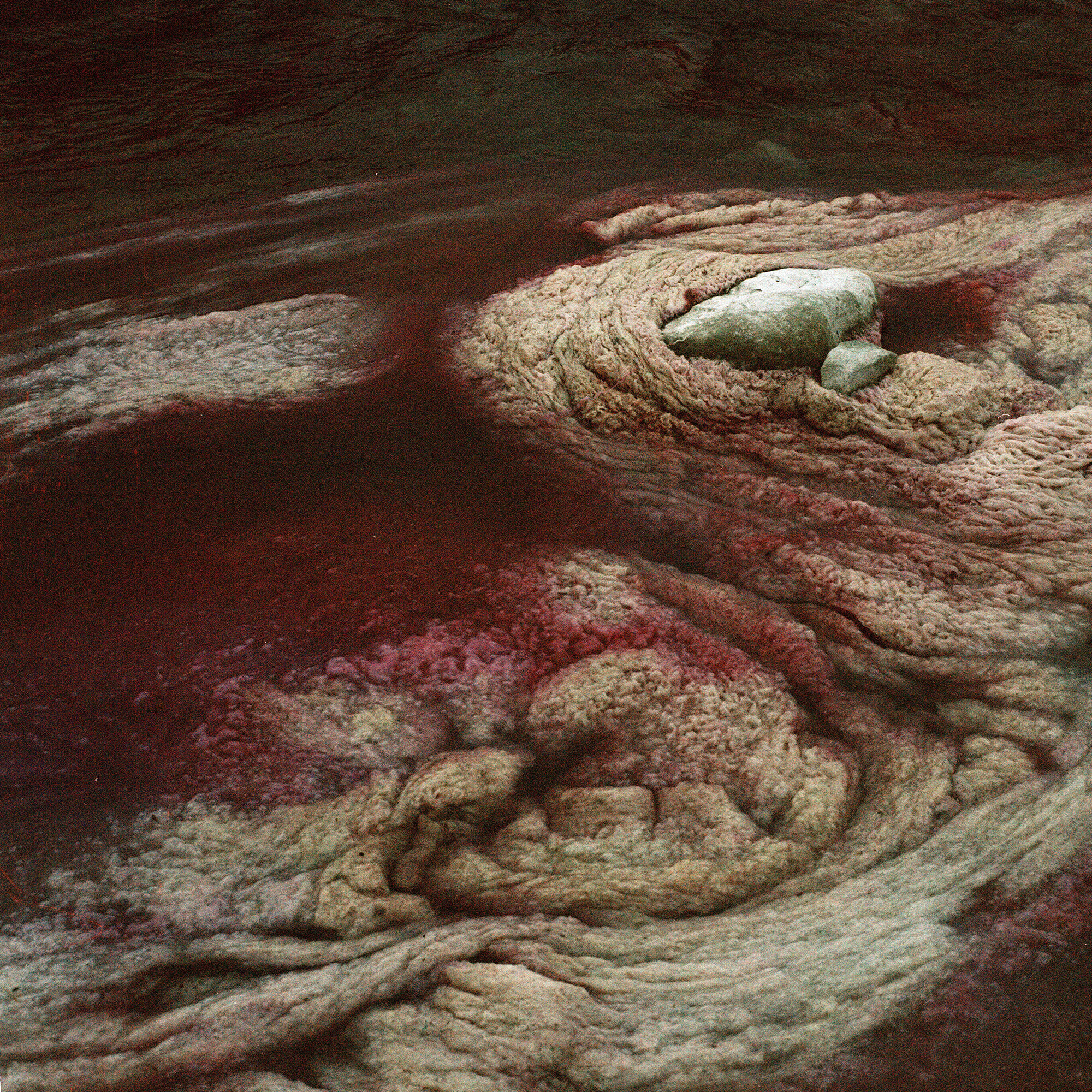

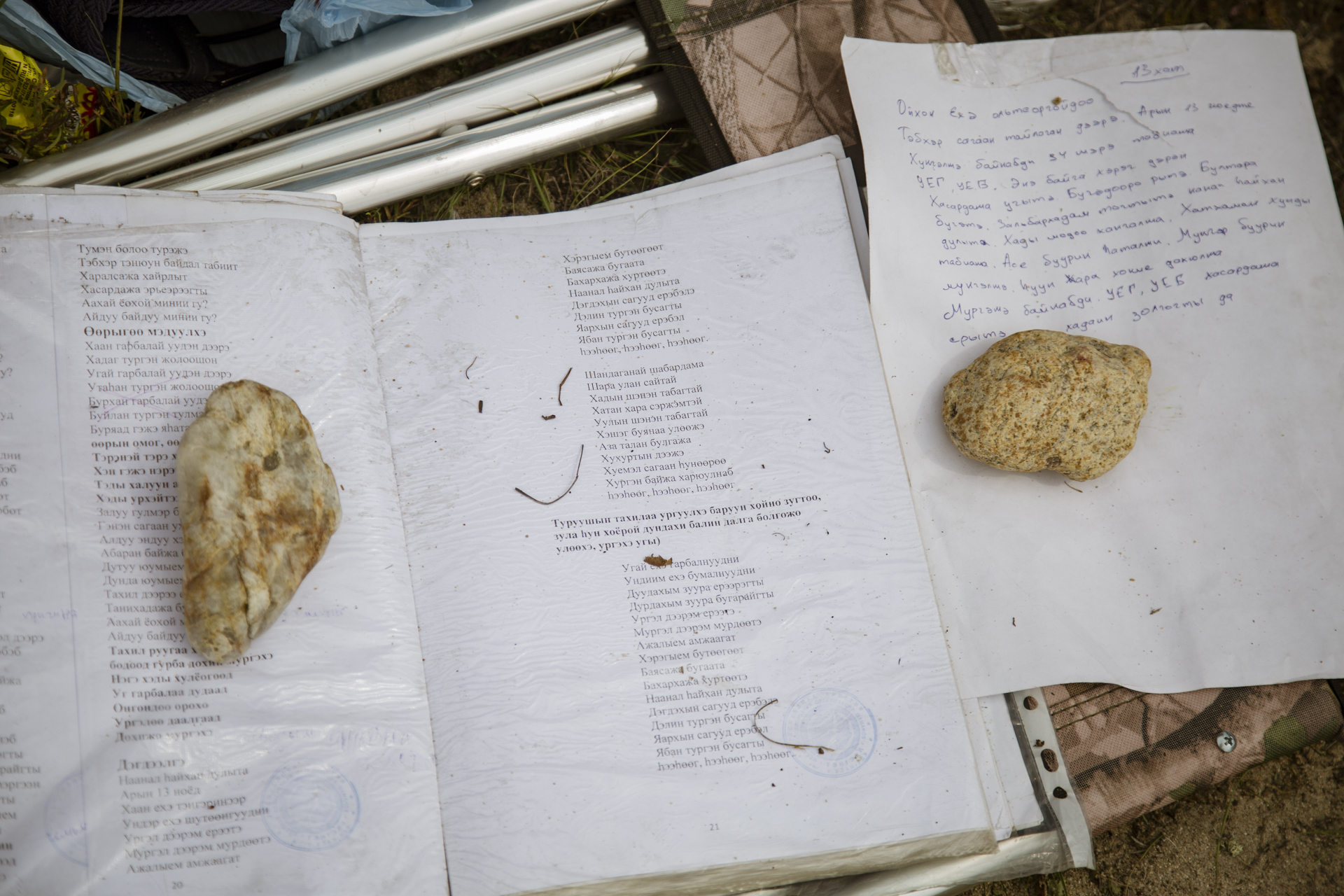

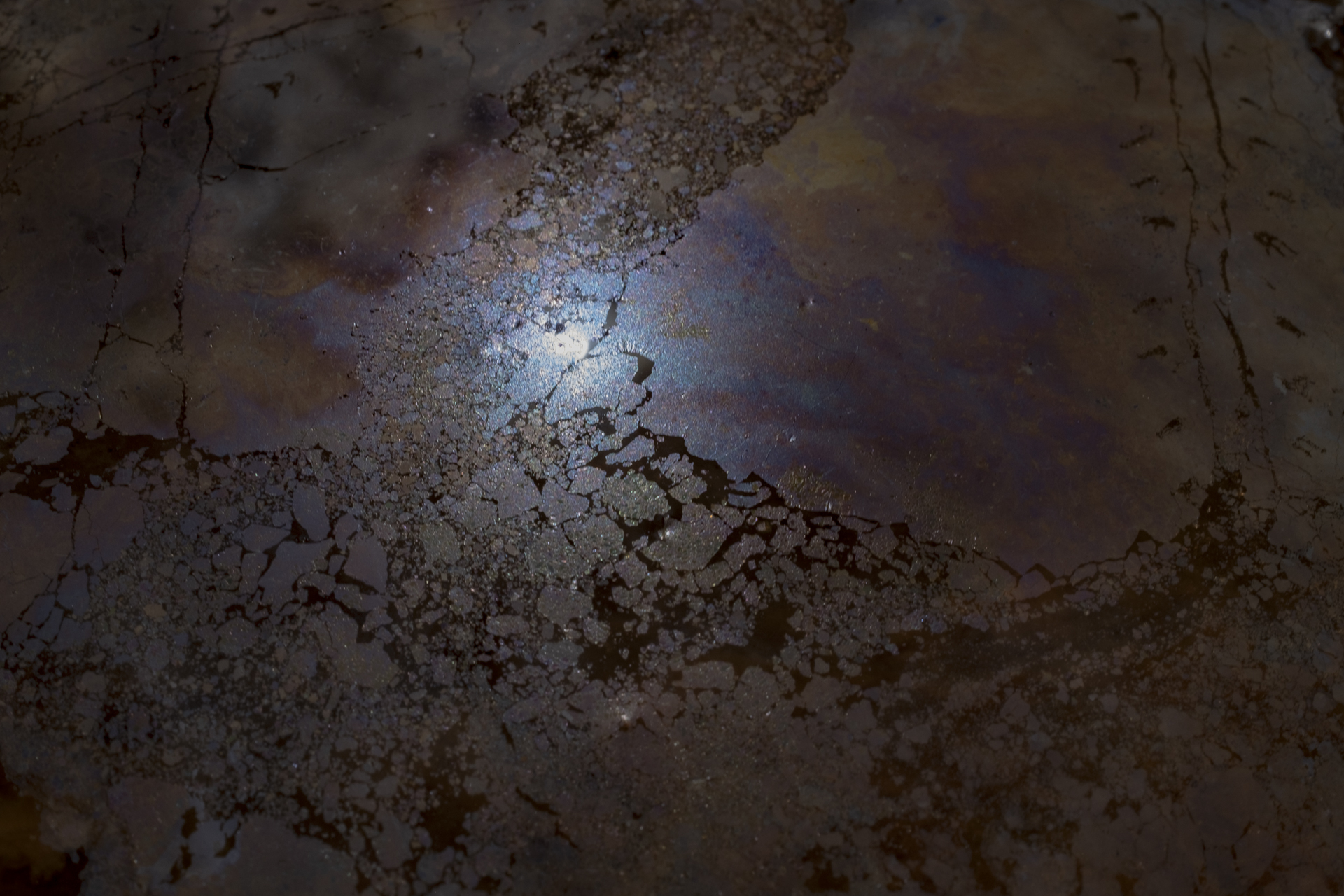

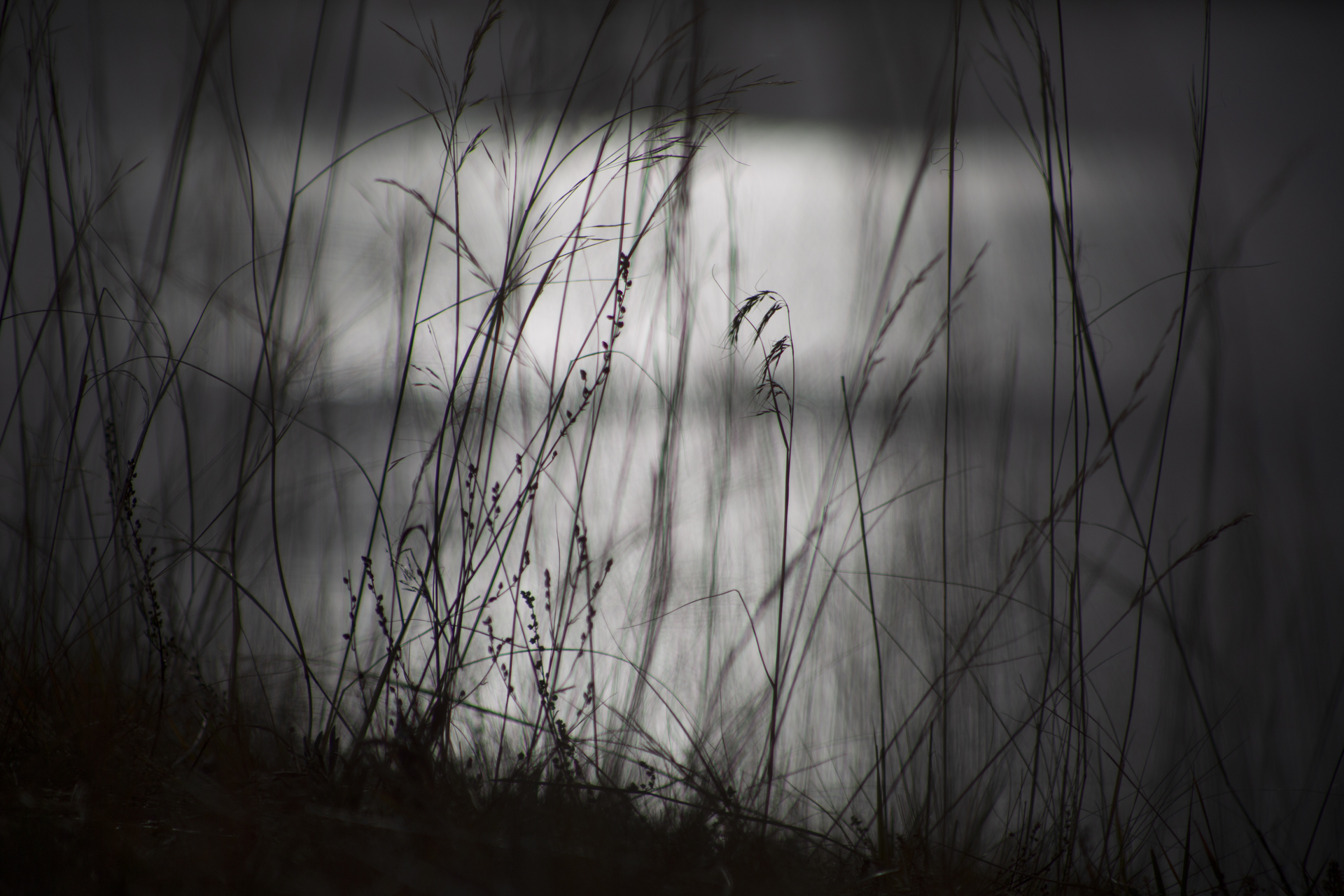

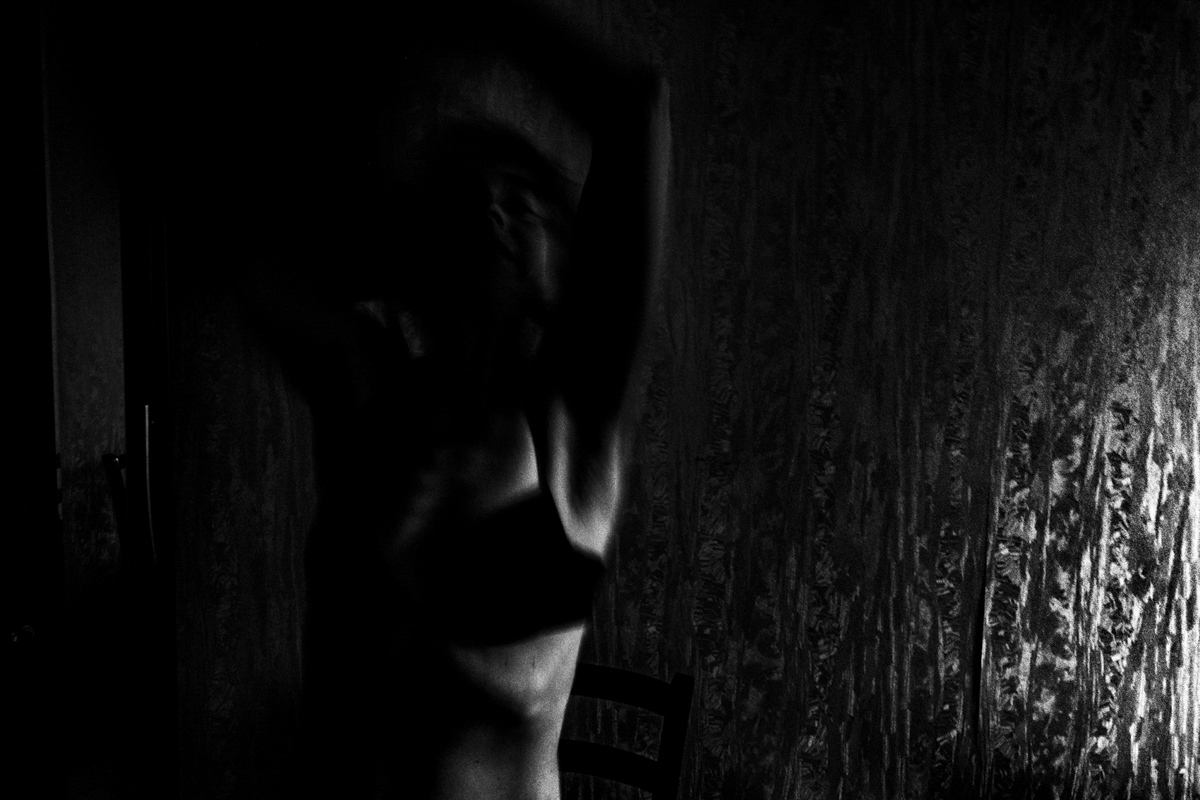

This post is part of a series by Todd Forsgren on his project Post-industrial Edens — photographs or urban and community gardens worldwide, which has been ongoing since 2004.

The popularity of urban and community gardens has seen a rapid rise around the world in the early 21st century. Gardeners cite a wide variety of reasons for this, from the practical and economic, to the political and philosophical. Globalization, and our increased awareness of abstract global issues, does indeed seem to be linked to an increasing number of people seeking this tangible and intimate connection to the landscape.

A renewed interest in self-sufficiency and local/organically grown food is apparent in the developed world. Increasing food prices and shortages have encouraged those in the developing world to grow their own produce. As populations continue to rise and the climate changes, it seems inevitable that such gardening projects will become even more vital and these needs more pressing.

While community-based agriculture has long been part of American culture, the allotment gardens reached their height during the Victory Garden program of World War II. During the war, gardens were planted according to a systematic plan for maximizing productivity from a small space. It is estimated that this popular program produced a full forty percent of vegetables consumed in the United States during the war, allowing more surplus food and resources to be sent overseas to support the troops.

Today, community gardening is seeing a large resurgence. These tiny plots of land can still be incredibly prolific: a carefully managed 20ft x 20ft garden can potentially grow $2000 worth of produce annually. The diversity of gardening practices currently seen in these spaces also suggests that community gardens possess other values to those who cultivate them.

Despite this long-standing tradition, community gardens still exist in a manner quite novel to American land-use philosophy. Notably, our concept of land ownership, often thought of in terms of a public/private dichotomy, becomes much murkier within these gardens. The gardens run the gamut from individuals cultivating their own plot to land worked in a truly communal manner. Gardens are often created on abandoned lots or publicly owned land, where individuals can rent space for a nominal fee. Yet individual land ownership is often quite tenuous.

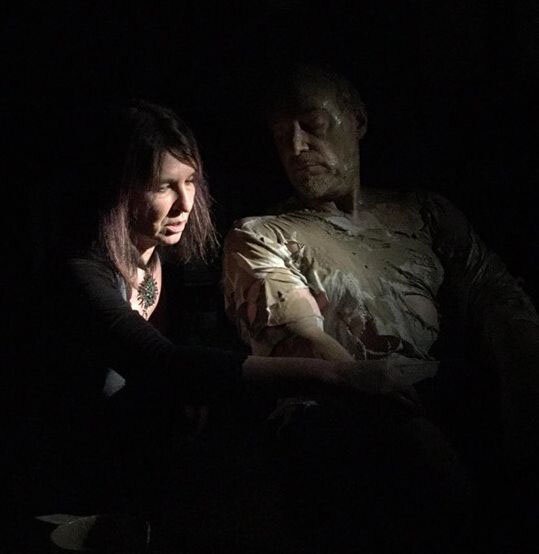

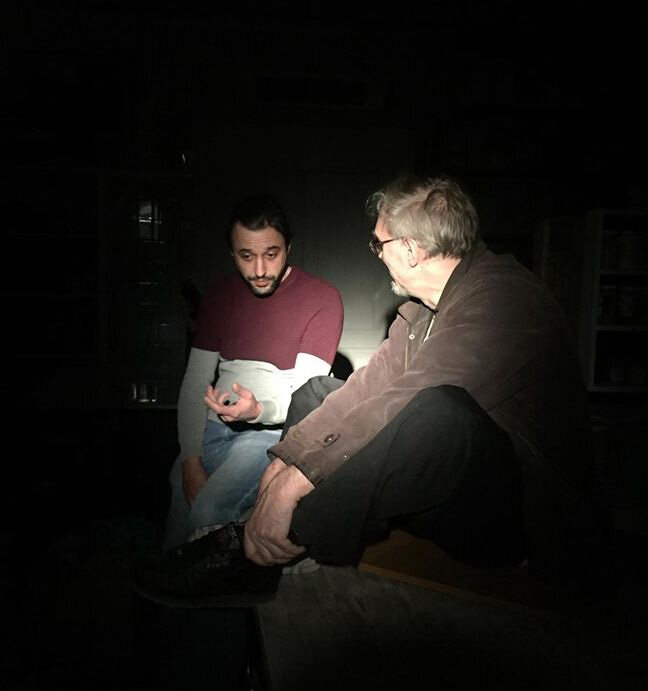

Perhaps due to this uncertainty and the initiative needed to start a garden, an especially strong sense of community often develops among the gardeners. These gardens often become central hubs of social integration. Conversely, the removal of this space from the ‘‘home”’ and ‘‘yard,” as well as the small financial obligation entailed, seem to lessen some of the sense of personal responsibility to maintain the garden. Meticulously managed plots are often next to plots that have been forgotten. In several instances, a particularly successful garden has even been blamed as a catalyst for gentrification of a neighborhood.

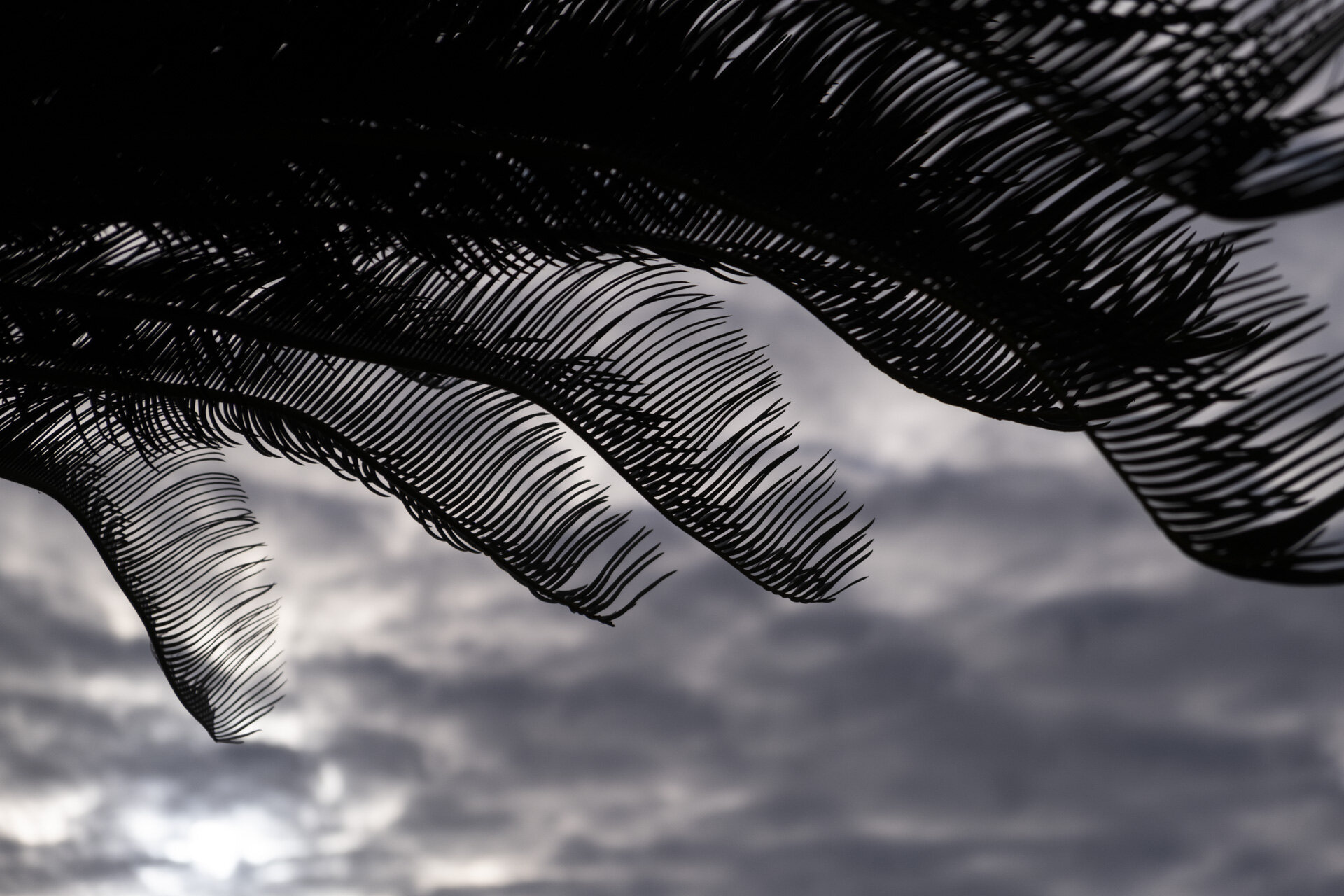

While some gardeners adopt the classic Victory Garden model, others employ more innovative and experimental gardening choices. Also, ideas from many other gardening traditions coexist in current community gardens, from English flower gardens to Japanese stone gardens. The modest scale of these spaces allows gardeners to personally re-connect to the land in their own way, but complete escape from the surrounding urban environment is impossible. The individual visions of community gardeners embrace everything from the pastoral ideal of the American landscape to a more realistic synthesis of this vernacular landscape.