Atlantika Collective Member Sue Wrbican's show titled The Iridescent Yonder recently opened at the Riverviews Artspace in Lynchburg, VA and was reviewed in this space on July 14. During Atlantika's monthly meeting, Sue walked us through the multi-faceted show, which includes photography, painting, and installation. She emphasized that the exhibit was conceived as a response to the tragic loss of both her brother, Matt Wrbican, and her mother within several weeks of each other. In fact, the exhibit centers around a large-scale collaborative painting of an oil tanker created by her brother Matt and two collaborators, Phil Rostek and James Nelson, in 1991. During the walkthrough, we were introduced to Phil, who not only helped us to appreciate the importance of Matt Wrbican's accomplishments, but also regaled us with tales about collaborative efforts the group initiated in the 1980s under the name "DAX," or Digital Art Exchange. Phil's recollections of their joint efforts and the early responses of artists in the 1970s to 1990s to important cultural developments, including the advent of the internet, proved extremely fascinating, and we invited him to elaborate on the very significant "paradigm shift" that he witnessed in art during this period. We hope that this series of posts will not only shed light on innovations in American experimental art during this period, but also flesh out the relevance and significance of Sue's recent work. You can read Part One here and Part Two here.

by Phil Rostek

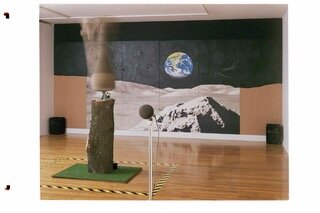

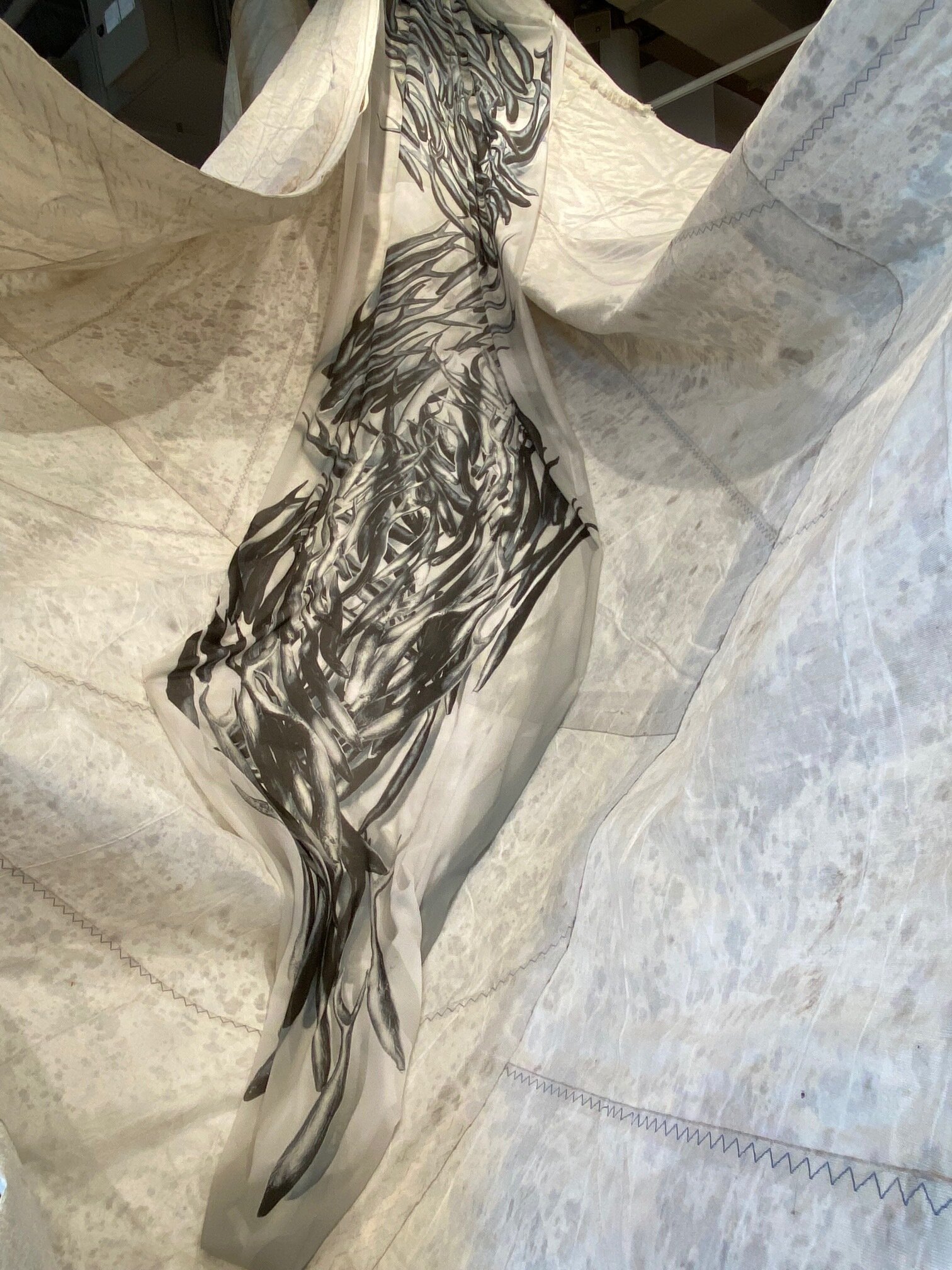

I was very happy to see the wonderful installation that the Oil Tanker received at the Craddock - Terry Gallery, Riverviews Artspace in Lynchburg. The Oil Tanker is comprised of four 6’ high by 4’ wide panels that are bolted together to make a 6’ high by 16’ wide surface. Matt and i were pretty deliberate in making something that would last; and the tanker survived 30 years of storage without much structural deterioration. It was stored in 2 commercial venues over the years - both were dry and climate controlled. The weight of the piece requires a solid wall for installation. To take the stress off the piece, the installation in Lynchburg supported the tanker in a rather ingenious way. I was delighted to see this beautiful presentation.

As i wax philosophically about memories of long ago, i hope i do not digress into far-fetched tangents. I see relationships everywhere and to a fault. Even the posts that support the Oil Tanker in this photo evoke symbolic significance for me. Being a helpless grammarian, it raises these two words in my mind: Foundation and origin. My mentor Robert Lepper defined design in several ways; this is one that i remember: “Design is the mutual dependence of the components of a system.” For me the collaboration that brought the Oil Tanker into the world enjoyed additional creative input in Lynchburg that further described what the Labyrinth show aimed to suggest. The components of a system had further described the concept of distributed authorship. A foundation was provided that was integral to the practicality of need; yet remained within the mutual dependence of a system.

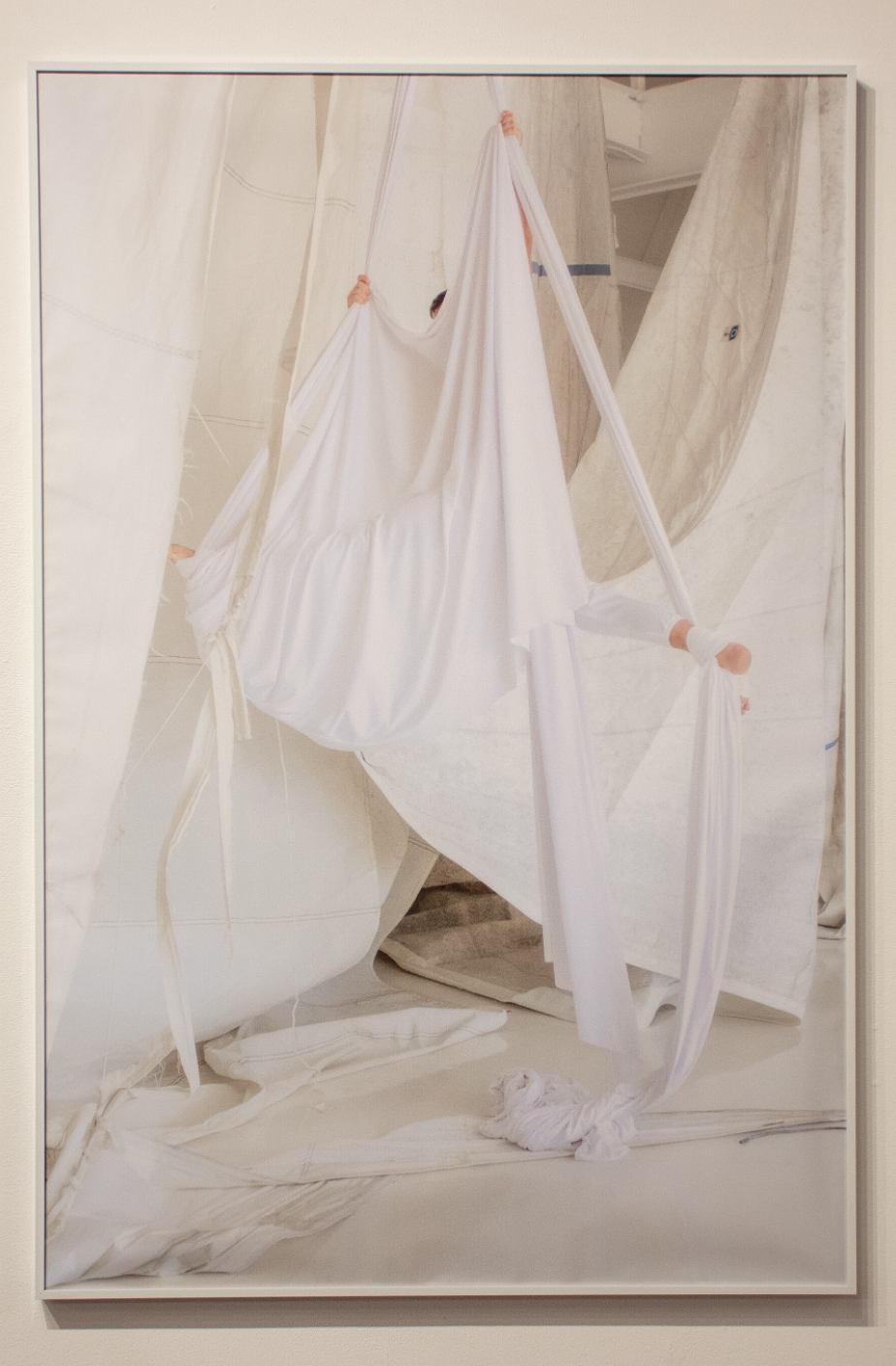

That thought raises implications about what we expect when we impose the notion of aesthetic into our consideration of most everything? Extraneous things, when removed, are perceived as improvements. The door then opens wider toward open ended thinking. It provides more room to take in more. When a system is efficiently contained, in the context of The Iridescent Yonder, it all becomes a component part within a larger schema. The very life of Sue Wrbican, the imagination and inclusion of Claire McConaughy, and the Oil Tanker all set sail together on some voyage into a 3 person installation:

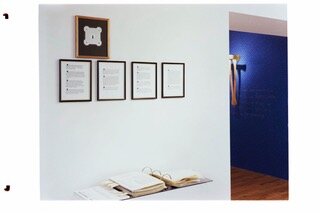

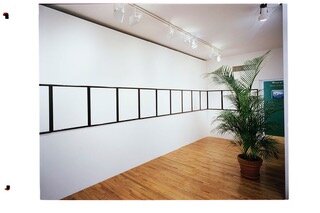

From Sue Wrbican’s installation “The Iridescent Yonder” at Riverviews Artspace in Lynchburg, VA.

Fragile Rainbow, Claire McConaughy, 120” x 40,” 2021.

If art and life are indeed a unison (or are at least believed to be a unison) and art and life together are considered to be an inseparable entity... relationship experience expands to appreciate subjectivity within a guarded attitude that is respectful of, not fearful of, subjectivity. I believe it is that zone that empowered Sue Wrbican to take on the The Iridescent Yonder. The loss of a mother and a brother, especially if we have shared similar trauma, needs little explanation. The impulse to place that in full view via the creative act stands close to what we all know, what we have all have felt, what we all call up in our hearts from time to time. The will to celebrate being alive in the midst of those considerations brings the term “Yonder” into rather sharp focus. Art and Life ponders eternity without apology and without a “look back,” as Claire said in her painting, “Fragile Rainbow.”

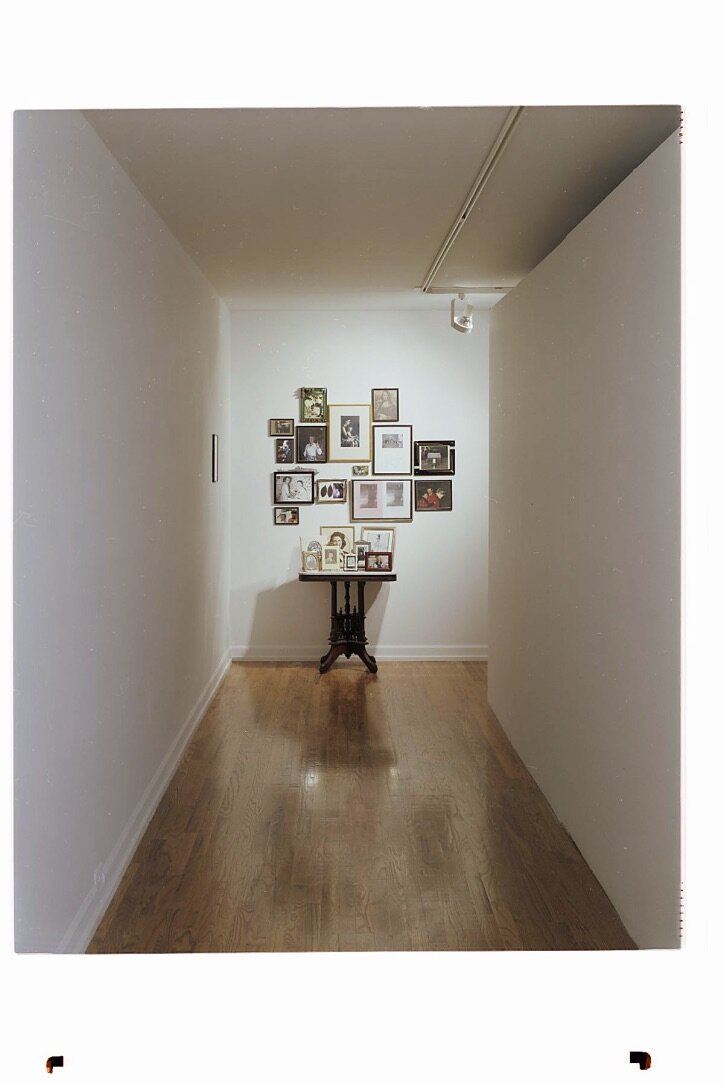

Plan for Labyrinth exhibition, Phil Rostek and Matt Wrbican, 1990.

The Oil Tanker was a portion of a larger show called the Labyrinth which closed with a long hallway. The wall and table presented pictures of the participating artist's mothers. My mother was alive then. Now i join Sue in the iridescent Yonder of recollection.

The awareness of experience as it is lived can include an awareness of some larger gestalt. This has engaged the minds of great thinkers throughout the centuries. Times of insight. Those times when things seem clear. Those times when you see yourself in the bathroom mirror - when you see what is there - not a memory that avoids the stark truth of what time has done to a face. Art can take us to this awareness. Art can move us into a receptivity to awareness. It can beckon us to engage the Yonder.

Ocracoke Path, Sue Wrbican, 53 1/4“ X 40 1/4”, 2017.

This is a view of that awareness, that disappearing path, that acknowledgement that things, including ourselves, move through time.

And so the sails that propel us through our lives are given pause in this presentation. Easy chairs help to anchor the sails. A reference to repose, a reference to times when there is time enough to step back and look at life, a look that seeks the mind not just the spirit. In my opinion this is more about analysis than it is about simplistic capitulations to recollection.

Sue speaks of a show where she includes her friends - as a way of getting a message out. In classic artistic reservation she does not spell out her opinion any further than that. There are only two friends in the Iridescent Yonder show. Both have to do with the show’s intent. Both were selected with care. Both retained a life of their own while mixed into relationship that was aimed at expressing the ineffable.

This is quite compatible with thought processes that were employed in making the Oil Tanker. Three artists acting in concert and acting with autonomy - at the same time. The desire is to avoid premature conclusions and the temptation of self proclamation.

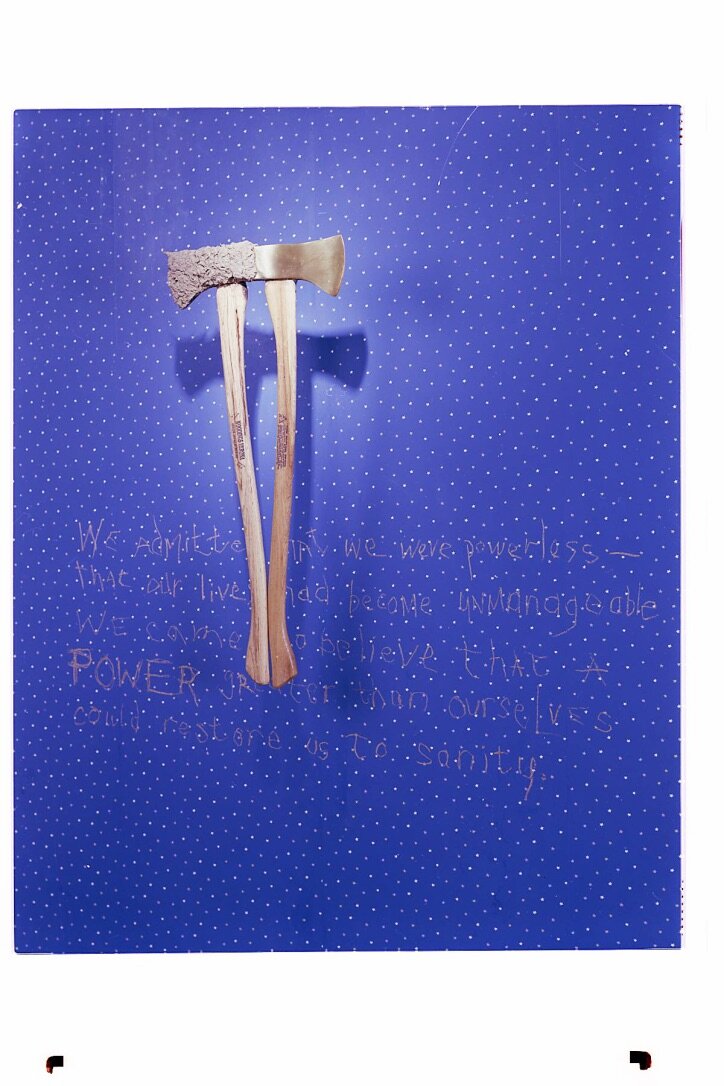

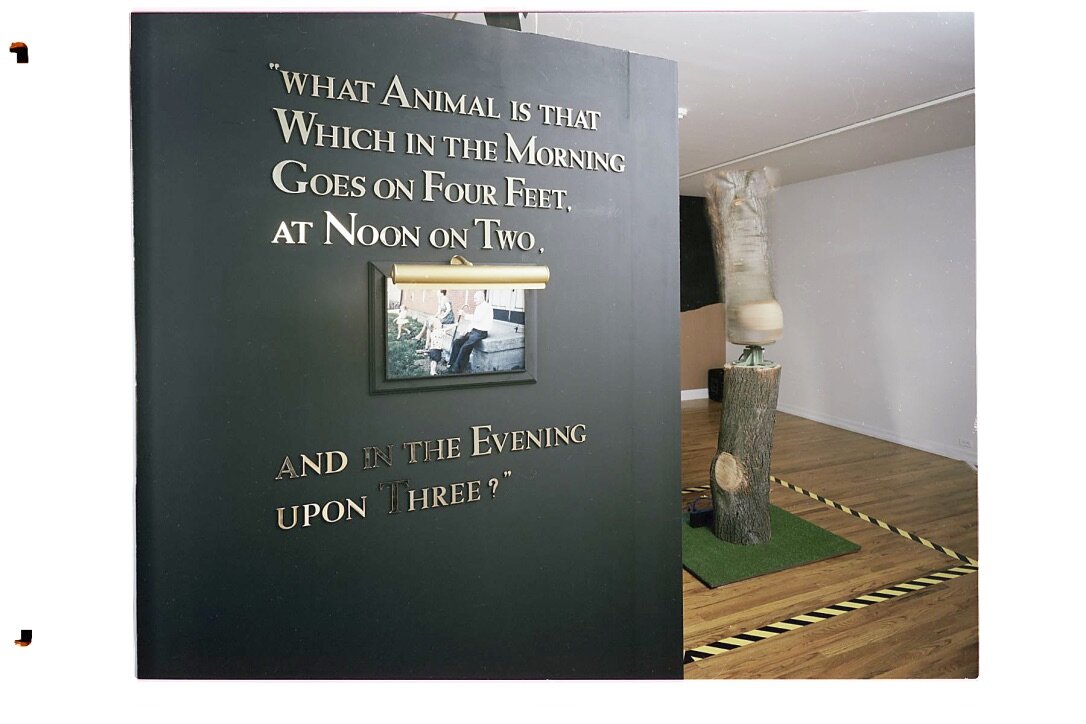

I close with this image from the Labyrinth show. It is a wing wall reference to the Oedipus riddle. The picture on the wall (that Matt Wrbican chose) depicts Sue, as a child in a party dress, running past her grandfather who is holding a cane. It is gesture that unnerves me a bit. It is so much in keeping with the sensibility of Matt Wrbican and the fusion of art and life that i have enjoyed with Matt and Sue over many years. I also knew Matt’s dear mother. i also knew her cats and her garden and her intellect.

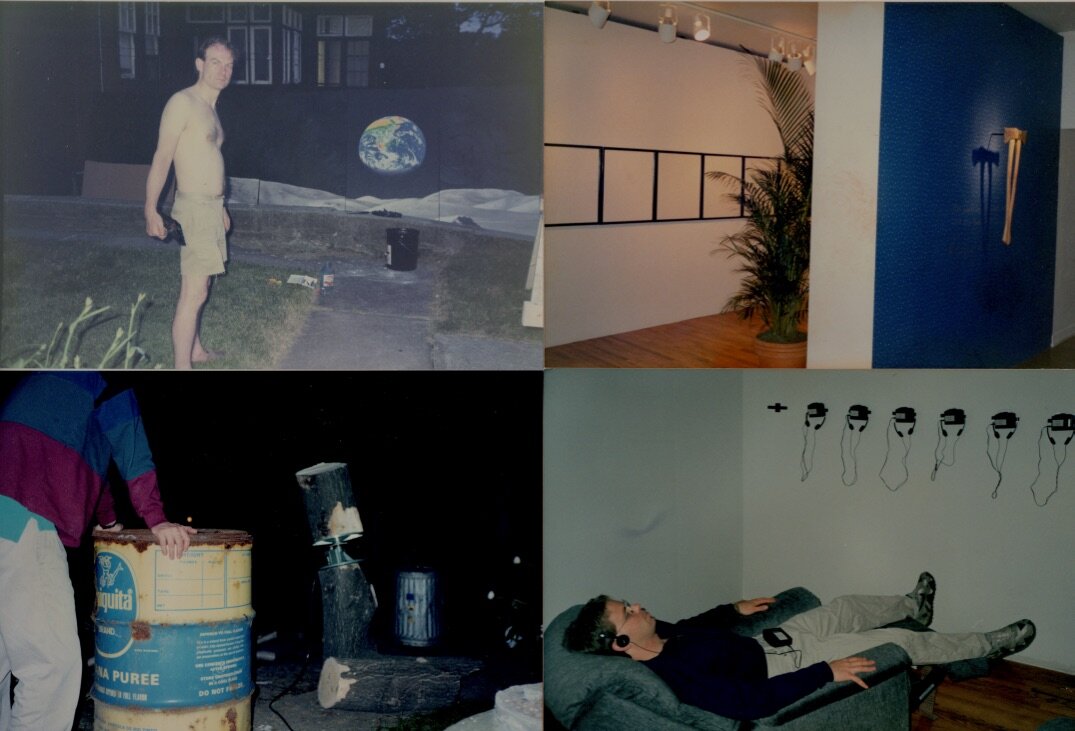

From the Labyrinth Exhibition, 1991.