Hi there, readers… Atlantika member Todd Forsgren here, talking about a recent project of mine. It’s a bit strange because it’s about a place I’ve never been to, yet I still put together a series of photographs about it. It is a very remote place, named after a guy who went to the same school as me: Peary Land. Robert E. Peary, who it is named after, went to a little school in Maine called Bowdoin as an undergraduate too, but he graduated more than a hundred years before me, so we didn’t overlap. I heard stories about Robert E. Peary when I was there though, and I used a bunch of his photographs for the first part of this three parted book. I couldn’t ask his permission, because he had long since passed away, of course. Actually, all the images in this book were made by someone or something else, in the arts, we call this appropriation. You can get a copy of the book on my website, here: Discovering Peary Land, but for now, I’m going to give you a quick intro:

An ice sheet covers 80% of the world’s largest island, blanketing it in white. Despite this stark landscape, Eric the Red named the island “Greenland” when he first landed on it over 1,000 years ago (c. 1000 AD). It’s widely believed that the name was an attempt at marketing: to encourage Viking settlers to join him. These settlements were likely never larger than 2,500 people and were abandoned in the 15th century. Even after the Vikings had left, however, the name stuck. But despite Eric the Red’s marketing ploy, Greenland is now the least densely populated territory in the world.

Almost 90% of Greenland’s 60,000 residents are Greenlandic Inuit. While Inuit peoples have inhabited the island off and on for over 4,500 years, the ancestors of most contemporary Greenlanders arrived while the Vikings were there—around 1300 AD. Today, the Inuit call Greenland “Kalaallit Nunaat,” loosely translated to “Land of the Greenlanders.” The origin of the word for Greenlander, “Kalaallit,” is not well understood, however, and its literal meaning has been lost over time. It does not bear a resemblance to the words for green or for land (qorsuk and nuna, respectively). Here, I find a compelling poetic context to set the stage for this photographic exploration: a Viking name that was intentionally false and an Inuit name that is a mystery.

The most remote part of the island is a region called “Peary Land” on the far northeastern tip. These 57,000 km2 are the location of two scientific research stations, but no active settlements. This was not always the case, as the remains of prehistoric villages dating from c. 2400-200 BCE, when the region’s climate was milder, have been found. The landscape of polar deserts and glaciated mountains is cut by deep Arctic fjords. Sparse vegetation sustains caribous, musk oxen, Arctic hares, and lemmings. These, in turn, sustain Arctic foxes, polar wolves, and polar bears. Colonies of seabirds, gulls, and geese inhabit the region in the summer, migrating south to avoid the long and dark winters. It is a delicate Arctic ecosystem that is extremely vulnerable to climate change.

I’ve never visited Peary Land, though I would certainly like to. In the meantime, this book considers the remote region through appropriated images from three sources: archival photographs from the first modern expedition to the region, corrupted satellite imagery from Google Earth, and geotagged pictures mined from Flickr. Like Greenland’s name, all three are interestingly misleading or incomplete.

PART I - Peary’s 1891 to 1892 Voyage

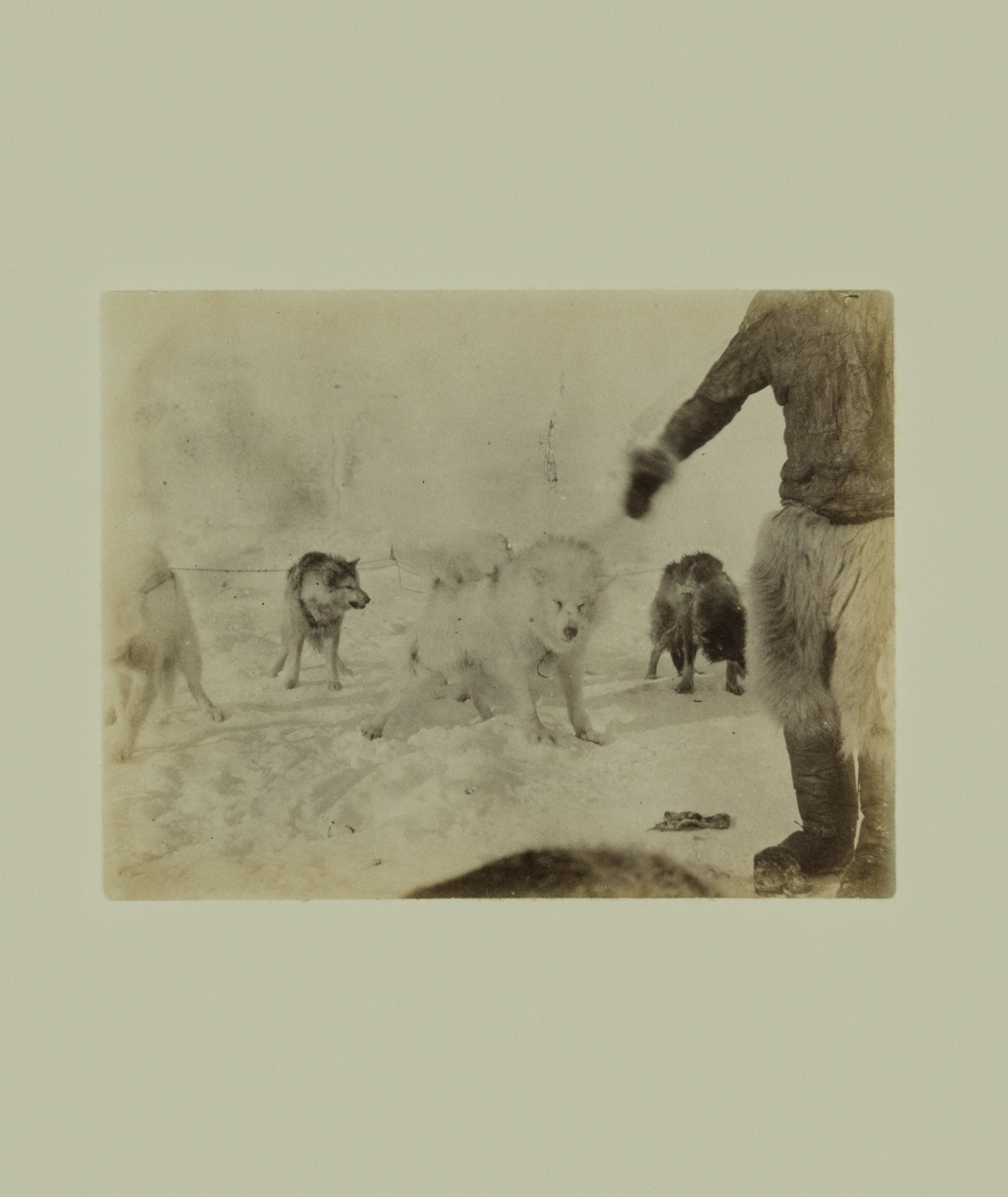

Peary Land was named after Robert E. Peary, an Arctic explorer who led an expedition to the region from 1891 to 1892. Landing in McCormick Bay, Peary then took a treacherous 1,000-mile dogsled journey crossing Greenland’s inland glacier to reach Independence Bay. He chronicled this “White March” and the rest of his expeditions to Greenland in colorful detail in a two-volume book with over 800 images called Northward over the Great Ice (1898).

As it was one of his earliest expeditions, notes for that 1891 to 1892 journey are far less precise than those of his other voyages. For example, his exact route over the ice is unknown. Furthermore, crucial information about the photographs taken on the expedition is damaged or seems to have been misplaced when it was transferred from Peary’s personal archives to the U.S. National Archives. The only remaining list of images is moldy and incomplete.

Identifying the photographs was challenging, as there seems to be little relationship between the numbers on this list and the images. The negatives have also disappeared, leaving only a single set of fading and decaying untoned albumen prints. Despite the difficulties inherent to this collection, the series of photographs is incredibly thoughtful in terms of both composition and subject. The cryptic identification of the images only added to my fascination... What a beautiful and mysterious landscape Peary and his team documented!

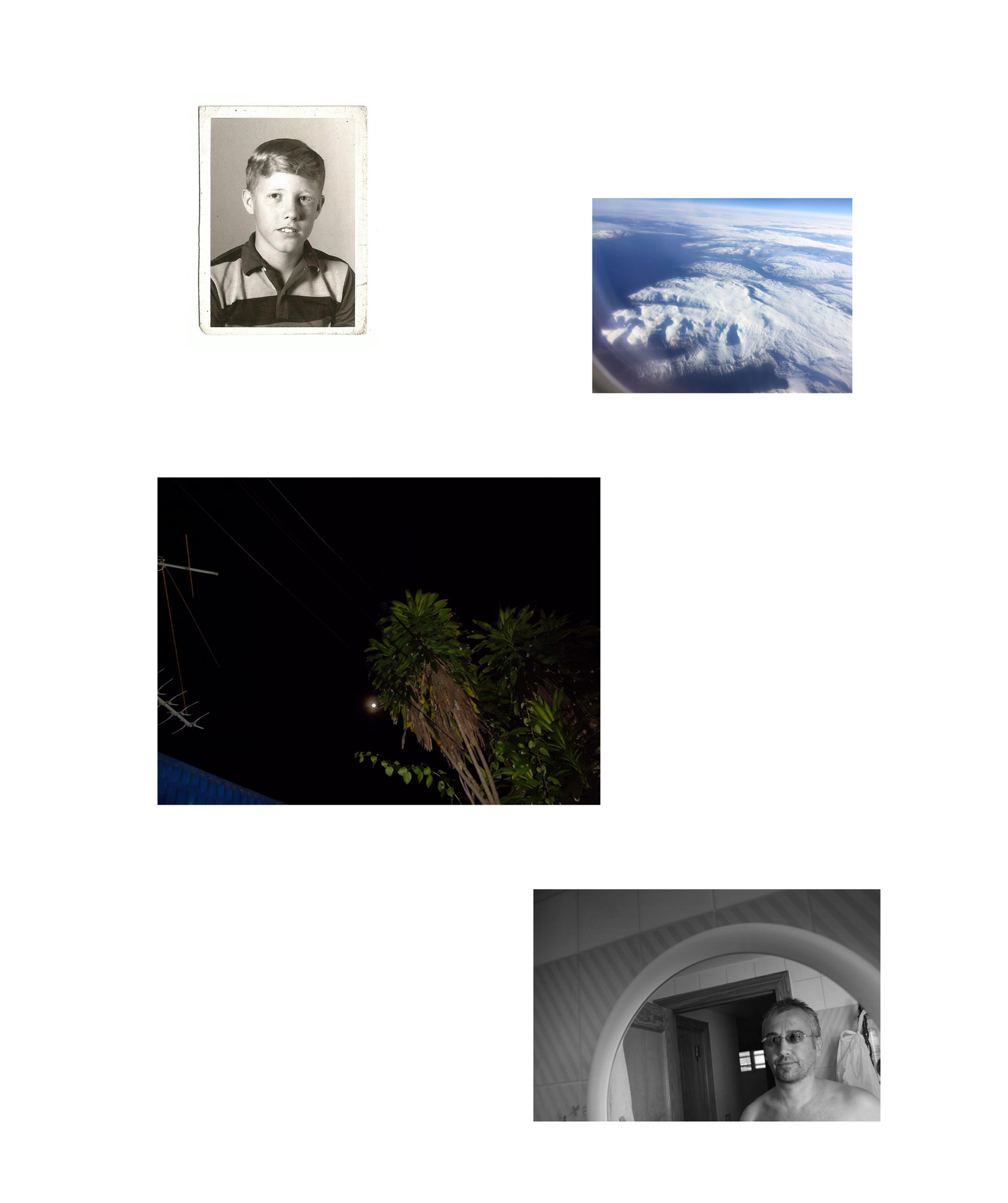

From these images I created a sequence that allows for my own narrative of the journey that emphasizes human’s relationship to this landscape. In this remote and grand place, the figure remains a mystery, at one moment miniscule and anonymous and the next, an imposing shadow.

PART II - Corrupted Google Earth Images

I first encountered Peary Land while exploring wilderness areas on Google Earth during a sleepless night in 2017. I slept less than usual that year. As a new parent of a wonderful but restless toddler, my travels were more limited too, so I resorted to using the computer more and more to go to the remote places that I couldn’t physically visit.

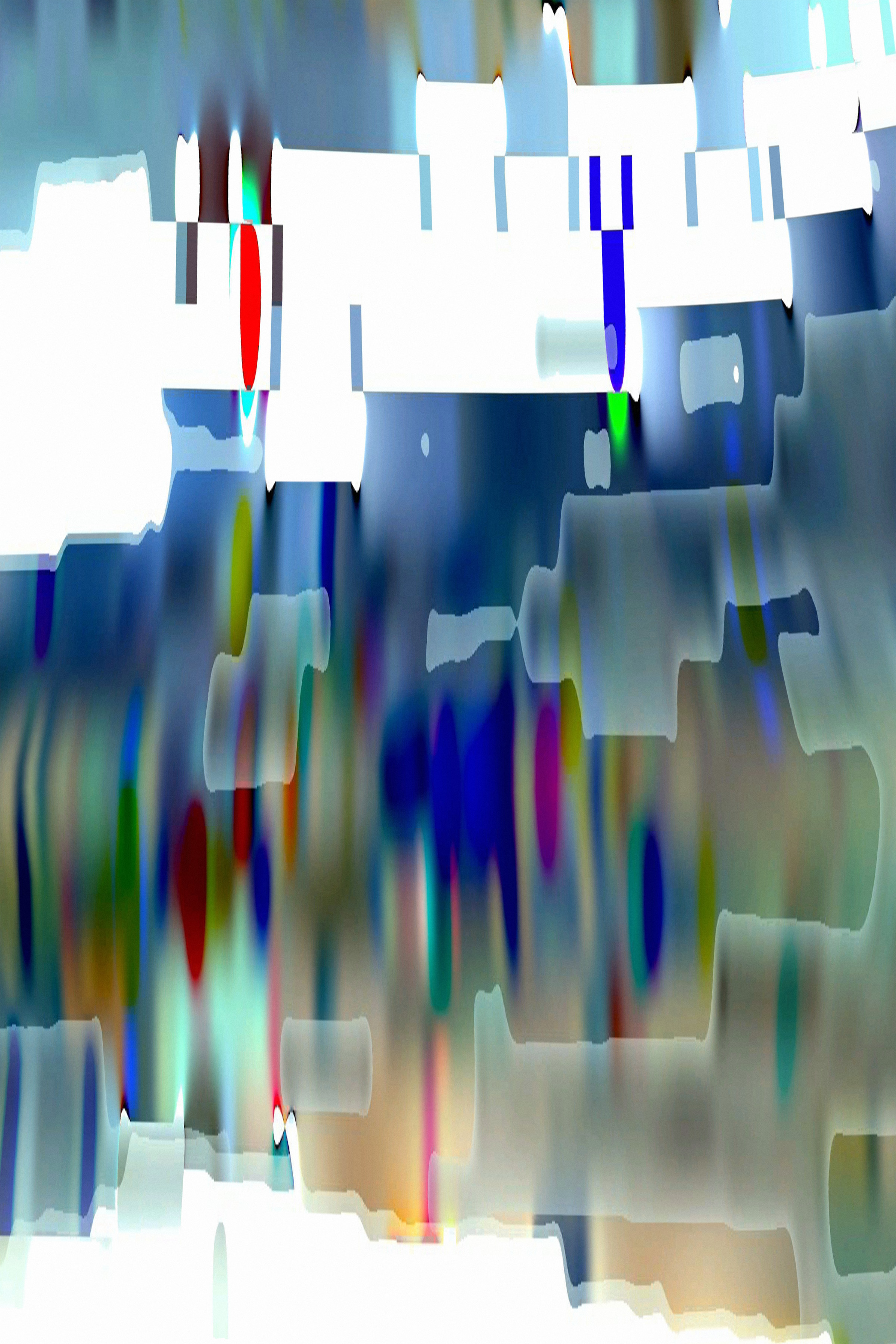

Initially, the images I saw were difficult to make sense of and the geology of this landscape was unlike anything I’d ever seen: saturated smears of color running from north to south instead of the brutal grey and white I had expected. This dreamscape looked more like a modernist painting than satellite photographs. The following twenty images are random plots I sampled from this region on Google Earth (and the title of each is the center of the plot’s longitude and latitude coordinates).

I did nothing to alter these Google Earth images, but they differ from the original satellite imagery in a number of ways. The most profound change is a glitch caused by the corruption of the jpg compression. Map projections for the northern latitudes then stretched the glitch vertically. Other data, such as elevation information, were added to the images, twisting the pixels further. I find the results both strange and gorgeous, a disaster of contrasting colors that paralleled another set of complementary colors: Eric the Red and Greenland.

PART III - Geotagged Images from Flickr

To add to my understanding of what Peary Land looks like today, I turned to Flickr. Using embedded metadata called geotags, I located images through their latitude and longitude and thus found photographs purportedly taken in the region. Sometimes these geotags are automatically added to files by the camera (if the camera has the proper GPS hardware, like the typical camera phone), although geotags can also be added to files manually, and thus tampered with or faked.

Being so remote, the number of geotagged images is predictably sparse. Some are believable. For example, several photos were taken out the windows of airplanes, showing glaciers, rocks, and clouds below. Perhaps these were taken by cell phones that weren’t turned to “airplane mode” and picked up a GPS satellite during a transatlantic flight. The only image I could find that might actually be from someone on the ground in Peary Land was a drastically underexposed image at very low-resolution picturing a dog sled team on a snowy

landscape, a subject not dissimilar from some photographs taken on Peary’s voyage.

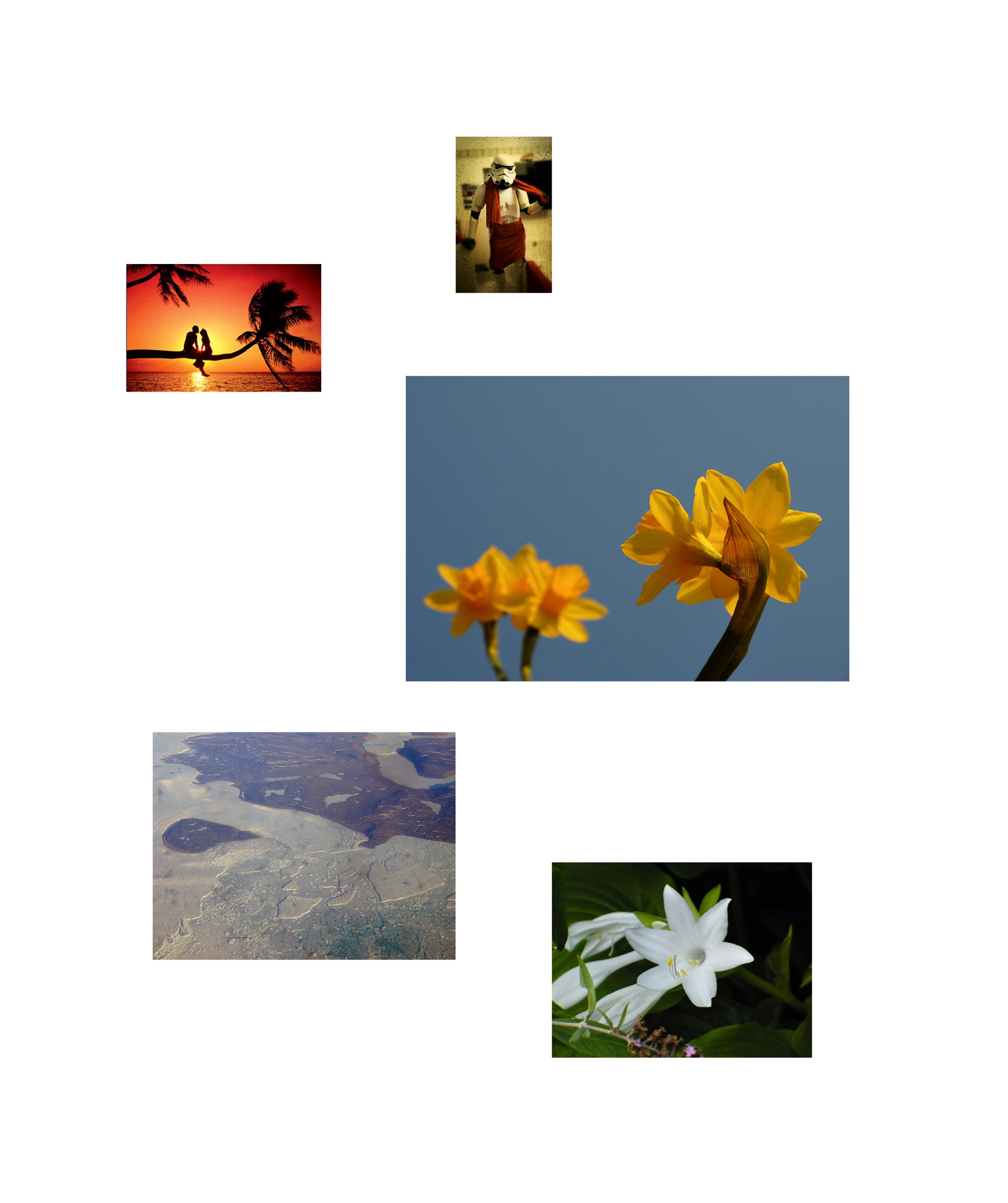

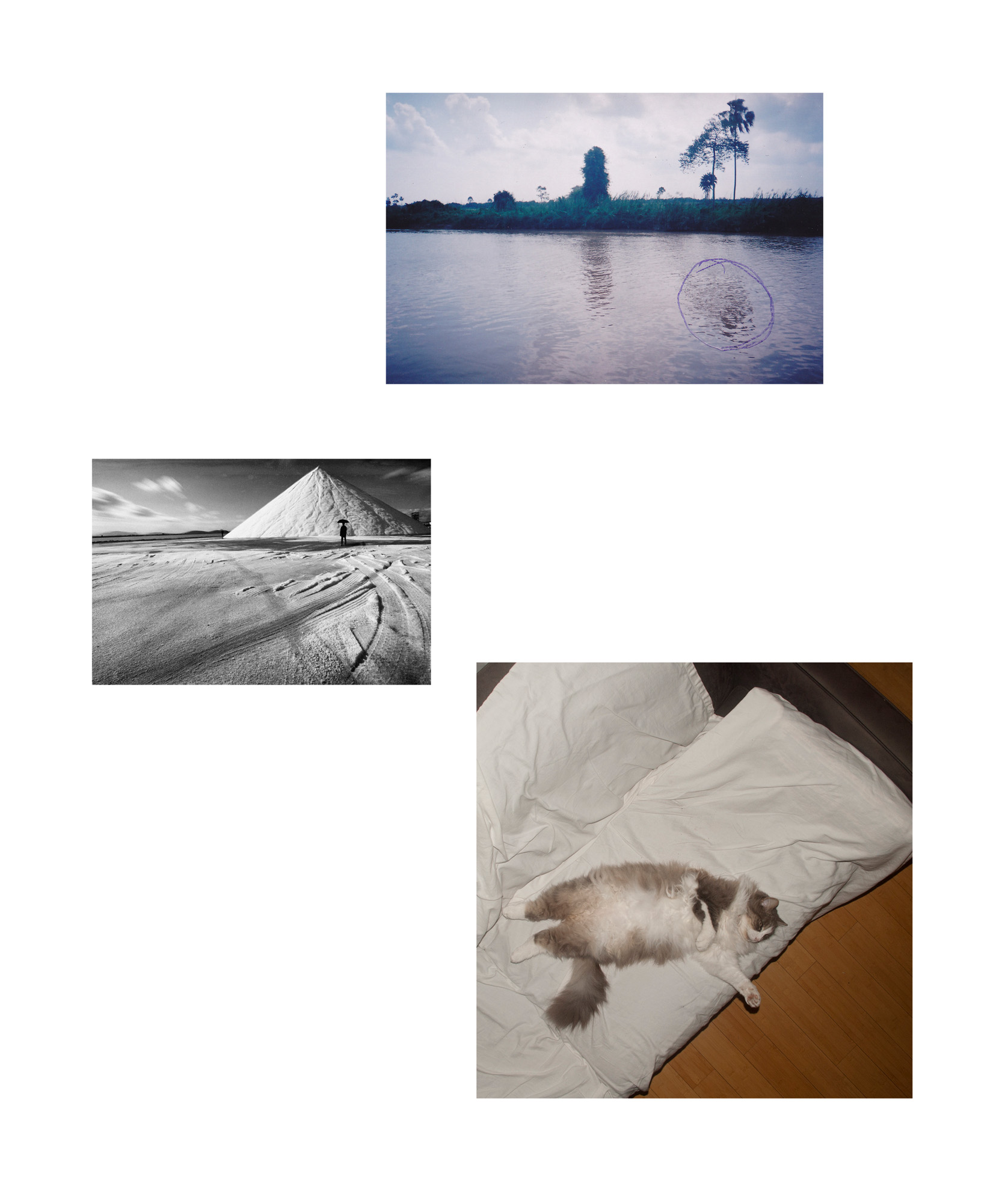

But the vast majority of the geotagged images were not actually taken in Peary Land. They feature everything from tropical palm trees and cityscapes to several scenes from Star Wars. Sometimes the reasons for the geotag are obvious, such as photographs of Santa Claus or polar bears. Most others, however, seemed more cryptic, or even absurd. Were these geotags intentional or accidental? Who are these other explorers who left such strange bread crumbs in this remote landscape?

I have arranged the Flickr images in a series of arrays, with the scale of each image determined by the largest pixel dimensions available. My arrangements emphasize both the discord as well as the formal and conceptual relationships I discovered in these images.